1. Beginning Questions - RonaldMah

Ronald Mah, M.A., Ph.D.

Licensed Marriage & Family Therapist,

Consultant/Trainer/Author

Main menu:

1. Beginning Questions

Therapist Resources > Therapy Books > DownRelRabbitHole- Assessment

Down the Relationship Rabbit Hole, Assessment and Strategy for Therapy

Chapter 1: BEGINNING QUESTIONS

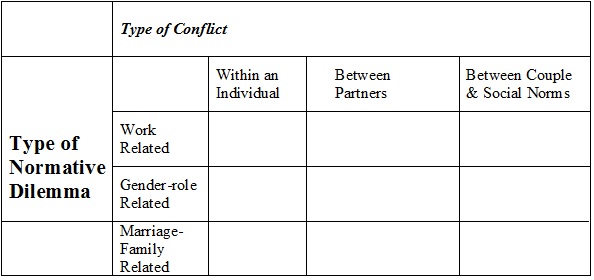

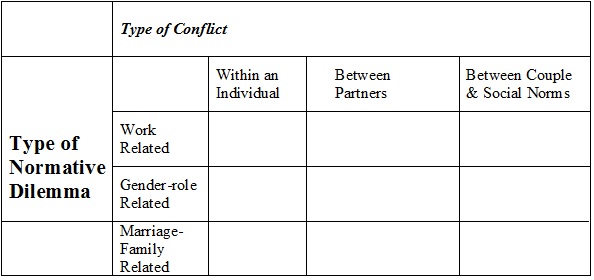

Initial assessment of the client and of dynamics with others or among the partners or members may begin with relatively simple but revealing questions. For example, the therapist can at the beginning of therapy, "What has been happening that you want to change or stop?" While this question may evoke responses about specific problematic behaviors of one or more individuals, it may evoke information about the current, past, and desired dynamics of the past relationships and the couple or family's system. For example, a complaint may be about problems with past life challenges or partners, changes for one or the other partner, changes in the couple's family life or work issues, and/or the interaction among these issues. There may be discomfort from a resultant imbalance and/or conflict from an imbalance. Forrest (1994, page 177) says, "According to system theorists, seeking balance or homeostasis among all of the roles and individuals is a desired state of being for members of a family. The desire for homeostasis provides the theoretical framework for understanding how change works in family systems. Changes cause disruption in the family-work balance…" and potentially among other facets of life. Individuals and the couple will try to re-balance or modulate or eliminate a disruption automatically either by returning to the old balance or by creating a new relationship among the dimensions. Seeking homeostasis causes both partners to act to recreate balance. Forrest uses the following chart that the therapist may find useful to illustrate various types of conflicts that may arise (page 179).

Initial assessment can be very structured and comprehensive. Beck and Crawford (2000, page 57) developed what they call the Couple Assessment Summary (CAO) which includes: genogram development, marital contracting, psychodynamic exploration, an assessment of the couple's commitment to the treatment, and encouragement for the couple to share responsibility for change. The CAO dedicates separate successive sessions to the presentation of the problem(s), individual developmental history, and the premarital relationship or courtship. In the consolidating final fourth session, the conceptualization including a written conceptualization is shared with the couple. The therapist shares his or her ideas about the relationship and how it has developed, gives a review of the presenting complaints, summarizes individual and family history, and reviews the relationship development and history. The therapist also gives his or her conceptualization of the problems and treatment recommendations. The couple discusses the report and seeks clarification if necessary. The therapist may direct therapy by addressing imbalances or conflicts gained from initial assessment (similar to Forrest's assessment chart) or from a more formal assessment process such as the CAS. Another therapist may be more comfortable with the flexibility of informal assessment. The therapist may initiate assessment and therapy with a set of four simple generic questions (three additional questions go with the question presented earlier) for the client (an individual, each partner or family member) to answer separately.

1) What has been happening that you want to change or stop?2) What have you tried before or up to now that has not worked well enough?3) What do you want to happen instead? What do you want to come out of therapy?4) Why now? Why not earlier? Why not wait for later?

These four generic questions can allow for a variety of responses. Each client may interpret and respond differently. The relatively open-ended nature of the questions can encompass various conceptualizations of individual, couple, or family problems. For example, the responses may fit into one of the three categories of complaints and problem presentations in relationship distress as hypothesized by Tremblay, et al, (2008):

1) overt relationship conflicts in the context of clinically elevated couple distress,2) emotional drifting and lack of love in situations where partners' distress is moderate or low, and3) requests for specific adjustments in the context of a well-functioning relationship. (page 138)

Therapy is then directed towards what is presented. Tremblay proposes that one direction of couple therapy is to eliminate dysfunction and/or improve areas of the relationship. This direction could be appropriate for individual and family therapy as well. However, in the case of emotional drifting the work focuses on "ambivalence intervention" to resolve vacillating commitment of one or the other partner. Couple therapy can also be about "separation intervention" to achieve constructive separation. Tremblay also subdivides couples based on initial diagnosis into three distinct subgroups

a) Conflictual relationship: There is significant distress for one or both partners and overt conflicts and dysfunction. Both partners want the partnership but either don't agree on how to do it or have failed to improve the relationship.b) Lack of love/desire: Despite emotional drifting from one another, but both partner want to save the relationship. Emotional intimacy is absent and their conflict and confrontation tend to be avoided despite incidents and disagreements.c) Generally well functioning relationship that requires specific adjustments: Overall satisfaction with one or both partners concerned that some aspect of their relationship or outside challenge may compromise the existing equilibrium. ((page 141)

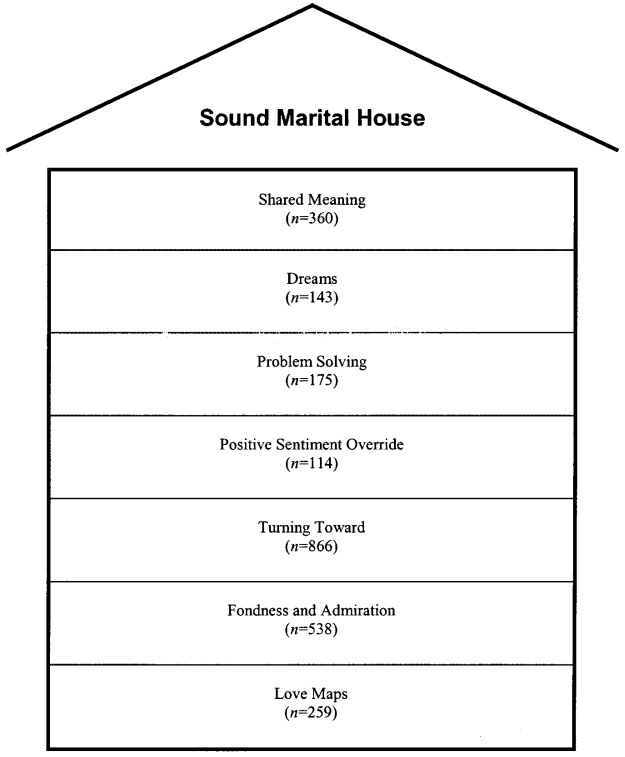

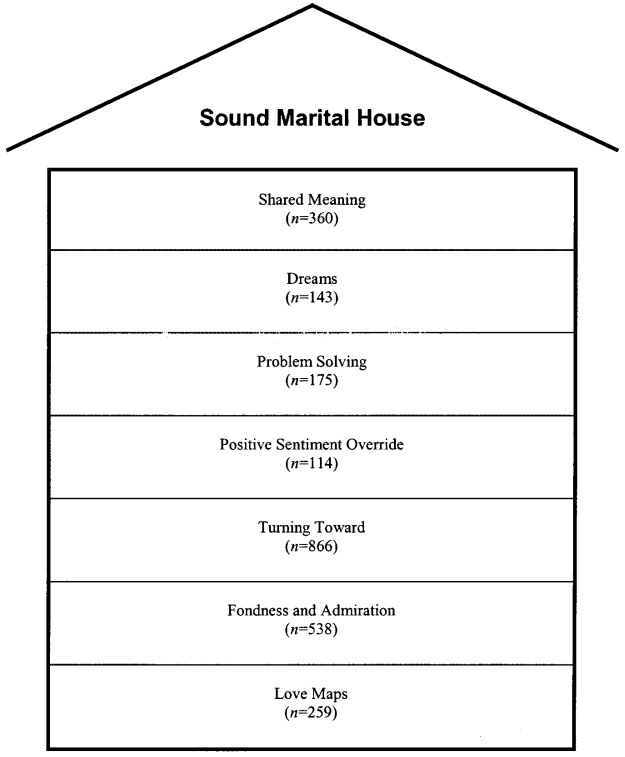

The four generic beginning questions can also evoke information relevant to how John Gottman's Sound Marital House conceptualizes healthy relationships. Hicks, et al, (2004) examined and interpreted Gottman's work. "The Sound Marital House is based on two staples of marriage: overall positive affect and the ability to reduce negative affect during conflict resolution. The seven levels of the Sound Marital House are love maps, fondness and admiration, turning toward versus turning away, positive sentiment override, problem-solving, making dreams and aspirations come true, and creating shared meaning (Gottman, 1999) (page 103)." The therapist may interpret or adapt the couple's responses to intent of the four generic questions into Gottman's concepts, or may use Gottman's concepts to expand upon and make more directed inquiries as to the soundness of their relationship structure- or of an individual client's quality of relationships to others.

(page 109)

Ellen Bader (2010) believes that there "are predictable reasons for why relationships fail." These reasons can shape the initial assessment process. The primary issues that most couples struggle with are:

There is a lack of development in either or both of the individual partners.They have a repetitive history of re-triggering emotional trauma in each other and not repairing it.They don't have the ability to repair when they hurt or do damage to one another.They lack skills or knowledge.

While the therapist may start the initial assessment with relatively open-ended questions, he or she may be looking for indications of the issues Bader or other theorists consider most important. Follow-up questions may probe for more details while keeping in mind such issues. Elements of or combinations of poor development, negative history, emotional trauma, and lack of knowledge, ability, and skills have created the intrapsychic turmoil, dysfunctional life choices, or problematic relationship. The severity of the issues may determine the goals of therapy. As a result in a couple, Bader believes that the couple's goals will fall in one of three main arenas:

1) The couple is coming to therapy for change, growth and development.2) They are coming to dissolve the relationship. Therapy is to enable them to say goodbye to one another, to go through a divorce or separation, and to get help with the kids and the parenting. Therapy is part of the process to resolve any resentment so not to fester and impair their future relationship or their parenting.3) They need help making a decision: To stay together or separate; whether to have a child; whether to take a promotion or move; whether to get married or not.

Bader recommends sending the couple home with five questions to answer. These questions are similar to the four generic questions I have proposed:

What type of relationship do you want to create? I give them examples to help get them started: "You might say you want to create a loving intimate relationship, a relationship with a lot of team work. You might say you want a more companionate relationship."How do you want to be as a partner? This is asking for a frank self-assessment. How do they in fact want to be? Do they want to be somebody who makes time for the relationship, somebody who wants to negotiate solutions that are working for both people? How do they want to be in their day-in and day-out life?What do you want to learn about yourself or the relationship? This is a request for cognitive knowledge that each partner would like to obtain. An example would be understanding your patterns as a reflection of some early childhood experiences.What do you want to stop doing? Common examples are blaming, name-calling, withdrawing, or avoiding conflict.

Sending clients home with these questions and having them report back their contemplation, discussion, and responses versus doing the process in therapy would probably be a decision based on the therapist's style. What is most important is that the information is gained and the client gains self-awareness and knowledge in the process. Bader also asks, "What do you want to start doing instead?" which is very similar to the question, "What do you want to happen instead?" Bader says in evaluating responses to her question, the therapist is looking for constructive behavior that each person will do when they stop doing the behavior that is contributing to the negative cycle in his or her life, partnership, or family.

Madden (2005) has "Five Useful Questions in Couple therapy." He points out that questions are used to gather information, but also that they are also clinical interventions. Small questions can change the tone, mood and direction of the session, while bigger questions open up the social and moral context of couple life. He feels five "bigger" questions open up new areas for discussion, avoid a narrow problem focus, and stimulate yet more questions. Madden, in his personal clinical development shifted from more orderly and sequential exploration of the couple to more free-floating questions and answers. He saw that stalemates in relationships were usually paralleled by a conversational stalemate. Therapist questions that stimulated curiosity cause both partners to more energetically engage with the therapist and each other. Madden felt questions seemed to offer the couple a "corrective experience" of being able to talk to one another differently. He observed that, "Sadness, guilt, blame and recrimination were replaced by curiosity, thoughtfulness and an enthusiasm for talking that I had rarely encountered in earlier couples work" (page 61). Madden's five questions are:

1) How did you get the courage to talk to a stranger about your relationship?…couples work carries the risk that your account of your feelings and experiences may be challenged and denigrated by your partner in front of a third person.2) Do you think the problems in the relationship are more to do with things inside or things outside the relationship?This question, and variants of it open up other ways of thinking about the relationship. For example,

How does your work affect your relationship with your family?When your children have problems, do you feel closer or further apart as a couple?Does the frightening state of the world conflict impact on your relationship?Do tensions in your families of origin affect your relationship? (page 62)

Close questioning about the social context opens up avenues that feel more manageable and seem potentially more receptive to change than fixed definitions of difference. This question may also elicit stories of a traumatic event, often the death of a loved one, that offer further reflections on the pain in the relationship, and opportunities for shared and overdue grieving for such a loss can be the most helpful part of couples work. Context questions offer the possibility of locating pain more accurately at its source. We know that in intimate relationships unresolved feelings from elsewhere are often projected onto one's partner. (page 62-63)3) What do you notice about other relationships that are like or unlike your own?This question invites a curiosity about other relationships and offers the couple the chance to identify their relationship expectations.4) If your relationship does improve, which of you will be more likely to have changed?5) Did you learn anything in your own family that has helped or hindered you in this relationship? (page 63)

The therapist will often find that starting the assessment process may be more important than any specific process or set of questions. In other words, having some… that is, any process or initial questions to get the client talking may be the critical element to begin assessment and therapy. For all the therapist knows, the client may begin to respond to a question or set of questions and go in a particular direction due to his or her intuitive or conscious urgency. Or, may respond in some unanticipated manner that the therapist may find provocative and worthy of further investigation- even at the cost of dropping a set of intended questions. Intentionally or innocently, the client may drop rich hints of vital issues. Initial questions for initial assessment may be open-ended while also pointed. A question about a client's family of origin presumes that there may be significant historical or experiential information there, while eliciting a tremendous unpredictable variety of responses. Within these responses may be cues to explore that deepen assessment. A prescribed process or set of questions may be useful primarily for the therapist to show confidence and competence to the new client. The therapist's implicit communication is that the therapy process is familiar to the therapist, and that the client will be guided and supported in the process.