12. Betrayal, Abandonment, & Rej- BDO - RonaldMah

Ronald Mah, M.A., Ph.D.

Licensed Marriage & Family Therapist,

Consultant/Trainer/Author

Main menu:

12. Betrayal, Abandonment, & Rej- BDO

Therapist Resources > Therapy Books > How Dangerous

How Dangerous is this Person? Assessing Danger & Violence Potential Before Tragedy Strikes

Chapter 12: BETRAYAL, ABANDONMENT, & REJECTION IN THE BORDERLINE

Chapter 12: BETRAYAL, ABANDONMENT, & REJECTION IN THE BORDERLINE

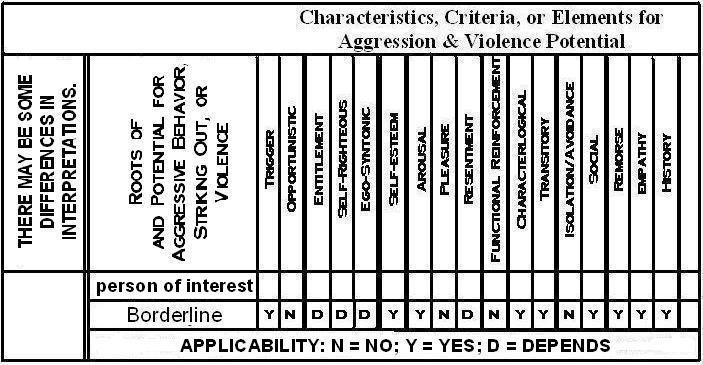

BORDERLINE: Characteristics, Criteria, or Elements for Aggression & Violence Potential

-- Code: NO=not applicable; YES=applicable; DEPENDS= Depends on other issues or occurs sometimes

BORDERLINE: YES, Specific Triggering EventBORDERLINE: NO, Opportunistic BehaviorBORDERLINE: DEPENDS, Sense of EntitlementBORDERLINE: DEPENDS, Self-Righteous AttitudeBORDERLINE: DEPENDS, Ego-syntonic PerceptionBORDERLINE: YES, Self-Esteem Gain or LossBORDERLINE: YES, Intense Emotional ArousalBORDERLINE: NO, PleasureBORDERLINE: DEPENDS, ResentmentBORDERLINE: NO, Functional Reinforcement (positive or negative)BORDERLINE: YES, Characterlogical Behavior/PerceptionsBORDERLINE: YES, Transitory Behavior/PerceptionsBORDERLINE: NO, Isolation/Avoidance BehaviorBORDERLINE: YES, SocialBORDERLINE: YES, Presence of RemorseBORDERLINE: YES, EmpathyBORDERLINE: YES, History

Mackenzie and Colton had a short marriage in their early thirties that produced a lot of drama and turmoil and their son RJ. Both of them had previous and subsequent partner relationships. They both have children with other partners: MacKenzie a 5-year-old daughter from a subsequent boyfriend, and Colton a 14-year-old son from his first marriage. RJ is 11 years old and been the battleground for 10 years around child support and legal and physical custody issues. Despite all their machinations, neither MacKenzie nor Colton has been ever able to have other than joint legal custody and virtually 50-50 physical custody. Although physical custody has been virtually 50% with MacKenzie and 50% with Colton, whenever the arrangements shifted to 49% to 51% one way or the other, they would take the other to court to get child custody support changed. When the physical custody was split exactly in half and RJ hypothetically cost each equally to care for, neither partner was able to assert that he or she needed child support. With a minor change in scheduling, one parent would demand child support for the 2% difference. Their current mediator (they had run through several mediators) and the family court judge ordered couples or co-parenting therapy because of their toxicity and its detrimental effects on RJ.

The therapist found two seething angry people in session. Both parents commit to doing the therapy in the best interests of RJ. They respectively roll eyes or stare stoically off into space as the other parent professed wanting RJ to have a healthy relationship with the other parent. In respective individual sessions with the therapist, they each give the therapist an earful about the crazy abusive behavior of the former partner. MacKenzie says Colton is controlling and abusive with all his relationships. She claims RJ and Colton’s older son are both intimidated by him. She says she and RJ and her younger daughter get along fine. She admits to some challenges with her daughter’s father as well. They broke up before their daughter was born. Colton in his individual session says MacKenzie is crazy. He says she is erratic and is out to punish him for leaving her. Colton says he has tried to be reasonable, but after all the crap she has put him through, he hates her. He claims the father of MacKenzie’s daughter told him that she is crazy and erratic with him around their 5-year-old daughter. Colton says he does not have the same problems co-parenting with his older son’s mother.

Further work and assessment with the two, takes the therapist to two individual diagnoses and a couple pairing diagnosis. MacKenzie has borderline personality disorder and Colton has narcissistic personality disorder. They are a not uncommon borderline-narcissistic pairing of partners. MacKenzie as is characteristic of individuals with borderline issues is highly triggered by anything that feels like she has been betrayed, abandoned, or rejected. “…among those with borderline personality features, cognitive distortions depicting jealousy and fears of abandonment may be articulated, especially in scenarios that elicit abandonment fears” (Costa and Babcock, 2008, page 395). As an individual with borderline personality disorder, she is usually very pleasant, reasonable, and functional until triggered. However, she had great vulnerability to anything that caused her to feel betrayed, abandoned, or rejected. Borderline issues- that is her borderline vulnerability and likelihood of being triggered however makes her aggression and violence both transitory and characterological. Her self-esteem is very fragile and cannot tolerate any insult. She is intensely aroused with deep distress and resultant anger. It is with the distress or despair and intense rage that she lashes out at Colton in numerous ways. In addition to verbal vitriol, she had pushed him, slapped him, kicked him, and thrown objects at him during their marriage. MacKenzie did not look for opportunities to aggress against Colton. To the contrary, for the longest time she deeply hoped against repeated disappointments that he would not do anything hurtful. However, in midst of her pain and rage, she felt entirely entitled, righteous, and in sync with herself to lash out. As a result, she has arguably become opportunistic in looking for ways to punish him for him abusing her so badly and so often.

A less severely borderline individual may relatively quickly recognize that his or her actions are inappropriate and unproductive. Earlier in the relationship, MacKenzie could admit that her retaliatory behavior was wrong and had remorse for the distress and pain she caused Colton. After years of battling however, she became increasingly more self-righteous that Colton deserves her vengeance. Both her responses and her change of heart are a pattern for her with Colton and also with other intimate relationships. It occurred before with friends, family, and especially romantic partners. Her empathy for Colton was greater earlier in their relationship but diminished from being worn down over the years. Before her hatred for Colton calcified, she was torn as her own abusive behavior distressed her. By now she had tremendous resentment against Colton, but early in the relationships there were no resentments against Colton specifically. If she had any, her resentments had to do with how a partner, including previous partners had mistreated her. While MacKenzie wavers feeling entitled and self-righteous about abuse (mostly emotional, but occasionally physical) of Colton and prior partners, when confronted she has to admit that it has not worked for her. She has been painfully punished for her process with relationship isolation and failures keeping an intimate partner she deeply craves.

Ross and Babcock (2009) found that “personality-disordered batterers in this study were significantly more violent toward their partners and inflicted more injuries than the non-diagnosed, control-group men. Additionally, the violence of men with different personality disorders appears to differ in its function. Within the context of an intimate relationship, BPD (borderline personality disorder)/comorbid men appear to engage largely in reactive violence, while ASPD (antisocial personality disorder) men tend to use violence both proactively and reactively. Differences in the type of partner violence enacted by ASPD versus BPD/comorbid men was not attributable to differences in criminal history or IPV (intimate partner violence) severity, as personality-disordered batterers were similar with regard to number of previous incarcerations, partner injury, and the amount of male-to-female violence in their current relationship” (Ross and Babcock, 2009, page 613). The personality disorder diagnosis for one or both partners reveals intensely embedded compelling issues that qualify if not cause aggression or violence. “Some have argued that PD (personality disorder) is not merely a correlate but an etiological factor in some men’s perpetration of violence (Ehrensaft et al. 2006). In fact, violence of characterological batterers, who often exhibit personality dysfunction and tend to be violent in all their intimate relationships, is thought to be one manifestation of their pathology (Babcock et al. 2007). Furthermore, while sexist beliefs have long been held as the primary predictor of wife abuse, more recent research indicates that PDs are more relevant predictors, with PD rates among partner-abusing men up to six times higher than rates among the general population (Dutton 2006). Antisocial and borderline personalities are among the most commonly referenced in partner violence research, and it has been suggested that both of these disorders be considered when investigating male-perpetrated, IPV (Holtzworth-Munroe and Stuart 1994)” (Ross and Babcock, 2009, page 607-08).

Individuals with personality disorders are by definition have dysfunctional emotional, cognitive, and behavior responses that are not readily changed. Their issues are most pronounced in interpersonal intimate dynamics often resulting in repeated failed relationships. Treatment including couples therapy that include such an individual is often extremely difficult as partner dysfunction is may be also replicated with individual-therapist dysfunction caused by the personality disorder. With MacKenzie as with other individuals with borderline personality disorder, the intense emotional arousal and virtually automatic behavioral lashing out creates emotional and relationship disruption and destruction. “...both people diagnosed with BPD and a subgroup of batterers exhibit abandonment fears, unstable moods, and unstable relationships. BPD is characterized by emotion dysregulation, fear of abandonment, feelings of intense anger that are difficult to control, and instability in interpersonal relationships (American Psychiatric Association 2000). Batterers with BPD may lash out physically at their partners when they become distressed as a way to regulate negative emotions” (Keltner and Kring 1998). (Ross and Babcock, 2009, page 608). “Calming down” or resisting being triggered, thus become interventions or changes that are difficult for the borderline to follow through on. The entries to therapy or change however are numerous for the individual with borderline personality disorder. Despite in the moment entitlement or self-righteousness, MacKenzie does not want to be angry and vindictive. She can identify with and feels badly how much hurt Colton and others have suffered for her behavior (at least, originally before her anger at him became embedded). She wants to be a different individual than the one who loses control and lashes out indiscriminately. Her self-esteem has taken a beating as she has been rejected over and over in relationships. She is motivated to not be alone.

The borderline individual asserts by his or her actions that he or she cannot suffer and survive the pain. This ignites and justifies abusive responses. The therapist or professional should assert that the borderline individual can suffer and survive. Most important to any process of change, the therapist or professional adamantly asserts that no matter how much the individual is triggered and aroused, abusive behavior or emotional or psychological, much less physical violence is never justified- and cannot be allowed. This can be an extremely challenging treatment strategy. Facilitating change with MacKenzie with her long history of conflict with Colton is more difficult than it would probably be with MacKenzie in a new or recently started relationship. In either situation, while the therapist or professional may get MacKenzie to agree to a non-abuse boundary, getting her to adhere to the boundary is much more difficult. One of the main strategies to facilitate no excuse non-abuse practice is to curtail MacKenzie’s continued and compulsive focus and attacks on Colton. In essence, “no matter how much you think Colton is an asshole, you may not retaliate. It makes things worse. You don’t have control of Colton, but you have to gain control of yourself. You must find a way to be hurt, be angry, and still not make it worse. Slow your anger and instinct to hurt back, and make a choice to make things better.” This approach, of course would be challenging with MacKenzie’s very intensive borderline characteristics.

The male perpetrator who has borderline personality disorder or borderline tendencies may be triggered by female violence, but “the mild violence of BPD/comorbid batterers was not predictable based on their partner’s behavior. There were no wife/girlfriend behaviors that were either more or less likely to precede the mild violence of their BPD/comorbid male partner than one would anticipate based on chance alone. Paradoxically, the erratic behavior, which is common among individuals with BPD, makes the unpredictability of these batterers’ behavior somewhat predicable. These men, meeting criteria for a disorder in which (affective and interpersonal) instability and impulsivity are characteristic, behaved largely unpredictably during a fight with a romantic partner. BPD/comorbid men reacted to their wives’/girlfriends’ displays of distress (i.e., pleading, crying, or other displays of negative affect) with severe violence. This behavior was in stark contrast to ASPD and ND/control group men, who were actually unlikely to become violent following their partners’ displays of distress” (Ross and Babcock, 2009, page 613).

Displays of distress are expected to trigger empathy, perhaps remorse for contributing or causing the distress, and activate nurturing behaviors from others. While this may cause the individual with borderline personality disorder to become soothing and supportive, it can also make him or her, but especially a man given gender expectations feel inadequate or a failure for not having soothed the other’s distress sufficiently. That could activate betrayal (the other person is supposed to be soothed or ok), abandonment (anticipating the other person may leave as a result), and rejection (prior nurturing efforts have been rejected, and hence the individual rejected). Rather than empathy and then, support, the borderline lashes out. If MacKenzie’s borderline tendencies were less severe, she might be more receptive or able to implement interventions to slow her arousal to reaction process. MacKenzie had reacted to previous partners’ emotional distress inconsistently. Sometimes, she was nurturing and supportive, but sometimes she reacted as if criticized or attacked. As noted earlier, adapting her process would have been relatively easier (while still difficult) with a new or beginning relationship without too much relationship history of triggering and lashing out. That assumes a non-personality disordered partner who is still invested in making the relationship work and not yet too emotionally shell-shocked by borderline abuse. With this couple, this strategy however became exponentially more difficult because Colton has narcissistic personality disorder.

The situation became more sensational with an incident exchanging custody of their son RJ. The history of miscommunication and major accrual of mutual resentments intensified a relatively simple problem. RJ not being ready and dragging his feet, along with traffic delays, caused Colton to be about twenty minutes late bringing RJ to the designated drop off/pick up site. Major mistrust and historical animosity anticipated further insult, so they snapped at each other brusquely. MacKenzie rushed RJ into her car, tossing his bag of clothes into the back seat. She jumped into the car, looked back quickly for traffic, and started to drive forward without checking in front, as she later claimed. Colton had retrieved RJ's backpack from his car trunk, which was parked in front of MacKenzie's car. He slammed down the trunk and turned without looking to go around the left side of MacKenzie's care intending to toss it into the back seat with RJ. He later said he assumed that she was waiting for the backpack. MacKenzie's car struck Colton knocking him to the ground, which caused a fracture to his wrist along with assorted scrapes. Colton swore that MacKenzie looked directly into his eyes as she accelerated into him. In a candid moment alone with the therapist, MacKenzie admitted that she could not swear that she did not see Colton. By then, she was filled with remorse despite her long held resentments against Colton. She did not know if she really saw or did not see Colton in front of the car, but she admitted that she had been seeing red from about five minutes after when he was supposed to be already there with RJ. While the circumstances and how it developed may have been unusual setting up an unprecedented and volatile situation, MacKenzie seeing red being so caught up in her rage was not uncommon.

Colton filed a police report against MacKenzie resulted in an investigation for felony assault with a deadly weapon (the car). He accused her of trying to kill or injure him. Colton asserted that there was a long history of her actions of aggression and abuse against him, including physical assaults. The therapist knew that they had many fights before, where MacKenzie had initiated physical aggression. Colton was much more of a psychological warrior in their battles. MacKenzie thought driving her to physical reactions was satisfying to him. She said he usually had a smug superior look when she hit him or threw something at him. There would have been significant legal considerations and complications if one or the other ex-partner had asked the therapist to testify in court. Both individuals have rights to keep information expressed in therapy confidential and neither could give up the other's right to maintain it or compel the other to give up his or her rights maintain confidentiality. In this case, Colton eventually decided to not press charges and begrudgingly accept it as an accident. Trying to put RJ's mother in prison, did not go over particularly well with RJ.

The therapist, other professionals including the police and the district attorney, and obviously Colton, however had vested interest in determining how physically dangerous MacKenzie was. Colton still had to deal with her, and half of the time RJ was with her. The therapist still needed to work with her in the co-parenting therapy to reduce her and their volatility, and stabilize their interactions. MacKenzie may not have been a stone cold killer, but she was not without potential for violence or completely not dangerous to Colton specifically, and possibly to others. Every consideration or characteristic of MacKenzie that suggested or reassured others that she ordinarily would not, did not desire to, or was likely to become violent or dangerous is challenged by her borderline personality disorder. The high emotional reactivity or explosive arousal when threatened by betrayal, abandonment, or rejection can be considered a characterological extreme form of frustration. The depth and intensity of arousal in the moment however is much more blinding to the individual than normal frustration. He or she loses any hesitation or adjustment from considering negative functional reinforcement and shame and guilt from ego-dystonic behavior. Only later can punishing consequence be clearly seen, normally too slowly to alter poor choices.

Discussion from domestic violence research of the propensity to dangerous reactivity of borderline men suggests high violence potential for both genders- and in other relationships and situations beyond couple's dynamics. If the MacKenzie and Colton were still in a relationship, there would be a high potential for continued domestic violence- MacKenzie against Colton. If MacKenzie were the larger stronger six-feet two hundred pound male partner instead of a five-feet two-inch one hundred and twenty pound woman, the physical discrepancy and potentially more aggressive cultural attitude could have made the domestic violence highly injurious if not fatal. However, gender and size do not always predict the degree of abuse. In same gender relationships and some female-male partnerships, the intensity and lethality of violence can be equally severe despite cultural generalizations. There may be cultural stylistic differences in the expression of aggression, abuse, or violence that qualify the degree of physical harm and lethality among various people. However, individuals with borderline characteristics and tendencies should be especially carefully monitored because of their likelihood to lashing out. The key consideration is if the outbursts are restricted to verbal, emotional, and assaults or whether they also include physical behavior that can be dangerous.

People in the borderline individual's sphere of interactions can try to avoid triggering the hurt that leads to rage and the lashing out. That however has limited effectiveness, since such an individual is hypersensitive and are unpredictably triggered by relatively arbitrary and innocuous words or actions. Choosing or avoiding words or actions by others is not so much the key solution or problem, but the borderline individual's vulnerability and propensity to being triggered the major consideration. Unfortunately, the simplest remedy to protect self and others from borderline abuse, aggression, and violence: emotional, psychological, or physical is precisely what the individual fears the most- rejecting a relationship with him or her or the environment abandoning him or her. On the other hand, this fear may offer a possibility for change and intervention. The only other possibility to achieve safety or diminish danger is for the borderline individual to commit to a clear set of behaviors and a process to address and alter behaviors and deal with the issues underlying the personality disorder. The threat and the experience of the simplest remedy may be necessary to engage the borderline individual in the other approach.

MALE DEPENDENCE

The core vulnerability for the individual with borderline personality disorder is often identical to those in other personality disorders such as dependent or histrionic personality disorders. Similar personal characteristics or issues include insecurity, fear of betrayal, abandonment, rejection, low self-esteem, along with significant depression and anxiety. Relative to potential for aggression, abuse, or violence, dependent personality disorder may be an otherwise unanticipated source for certain people. The symptoms of dependent personality disorder can be split into two groups. One group concerns issues assuming responsibility, making decisions, and showing disagreement. The other group is about fears of being abandoned and helpless. Men who do not have trouble asserting themselves would not therefore be ordinarily diagnosed with dependent personality disorder. However, they may have significant anxiety about needing nurturing and support, which “is compatible with a surprising degree of aggression. The need for care and support can lead to abusive behavior, intimidation, and violence. A jealous man who abuses his wife or partner may be displaying this kind of dependency. Dependent men are especially at risk of becoming abusers when they fear that the partner is about to leave or getting too close to another person” (Harvard Mental Health Letter, 2007, page 3). The therapist, professional, or concerned person should consider male dependency as contributing to aggression, abuse, or violence potential.

The therapist, professional, or other concerned person should be vigilant for abusive behavior in men with dependent personality disorder. While women with the same diagnosis may be similarly prone to abusing partners, but gender cultural standards may direct them to more passive-aggressive rather than overtly aggressive behavior. More overt violent or aggressive acts by anyone, but especially by women may also be culturally grouped together as borderline personality behavior. The learned and socially sanctioned outlets for dependent or relationship anxiety for males and females may be distinctive enough that they may be labeled or attributed to different rather than the same sources. Males from childhood are allowed and expected to express physically including aggressively and even violently, while females are often expected and encouraged to express distress and anger verbally. One should be sensitive to any type of violence, especially relational violence and the potential: emotional, psychological, verbal or non-verbal. However, physical assault requires a greater level of ethical and legal requirements over and above clinical requirements. Boys are expected and tolerated to engage in physical confrontations both playfully and over territoriality and dominance. Females are expected to deal with the same issues through verbal and emotional communication. Female failure to manage such issues and resulting aggression, abuse, or violence, thus are characterized in socially terms such as being catty, bitchy, or nasty, and in psychologically technical terms such as borderline and dependent personality disorder. Male aggression may be assumed to be largely from culturally training, bullying, or narcissistic issues- all of which are more or less accepted or sanctioned as normal male behavior, rather than some vulnerability as seen in borderline or dependent personality issues.

As it often happens with other males, Johann could not deny his dependency needs, or minimize them sufficiently despite family and cultural training enough to be unaffected. However, like many men he did not identify his dependency traits as such but expressed it in other ways. “The results of several studies reveal a strong correlation between dependency traits in men and Axis I disorders, particularly depression. Nietzel and Harris (1990) assert that dependency needs appear to predispose individuals to depression. Researchers offer several possible explanations for this correlation. Bornstein (1992) suggests that when a dependent individual experiences a stressful life event that threatens his dependency, he is more vulnerable to depression. Overholser (1996) proposes that high levels of interpersonal dependency correlate with maladaptive social functioning, which plays a role in vulnerability for depression. Birtchnell (1988) asserts that dependent individuals are vulnerable to withdrawal, denial and rejection and, in response to such actions, often become depressed. Chodoff (1974) believes that patterns of personality, the dependent personality for example, predispose to depression. Brown and Silberschatz (1989) found a correlation between dependency and self–criticism and that both are related to depression” (Berk and Rhodes, 2005, page 191-92).

The fear of losing the intimate figure is a central theme for dependent individuals. It is consistent with seeing oneself as a failure, self-condemnation, and self-criticism. Ownership of such feelings while often intense however is also verboten for many men. This creates a bind that has potentially harmful consequences. “Another interesting finding is the comorbidity of dependency traits in men and spousal abuse. Controlled studies and clinical accounts strongly suggest that men who perpetrate spousal abuse are often highly dependent on their partners (Murphy, Meyer, & O’Leary, 1994; Sonkin, Martin, & Walker, 1985). In a more extreme example of the relationship between dependency traits and violence, Ainslie, in his book The Long Dark Road: Bill King and Murder in Jasper, Texas (2004), explores the dynamics that drove Bill King to join a racist group and eventually to commit murder. His book suggests that, in an effort to satisfy their need to be accepted and to defend against their terror of abandonment, some men will go so far as to engage in antisocial behavior to maintain their sense of belonging to a group” (Berk and Rhodes, 2005, page 191-92).

When a dependent person, especially certain dependent men is examined using the seventeen criteria, the profile is very similar to the borderline personality disorder. While dependent men may have the same emotional and cognitive experiences fearing disapproval and becoming submissive trying to please partners to avoid abandonment, gender role standards may result in some important behavior differences. Frequent and constant practice behaving differently than their true self- acting according to a false self is a risk for both men and women. If getting angry is not egosyntonic with ones sense of self, depression may be the result. Although, the anger offers some relief, guilt and shame may follow. Rather than reconciling the discrepancy between the true or ideal self with the real self through compassion and understanding ones process, the false self asserts instead to avoid the emotional and psychological stress of addressing it. Other non-productive behaviors may arise to avoid dependency anxiety. Male cultural standards of omnipotence, strength, invulnerability to hurt or loss, and other commandments to be "tough," create a dilemma for the dependent man. It is entirely ego dystonic- against his self-definition of manliness to feel anxious, sad, hurt, or loss. Aggression and violence, implicitly or explicitly depending on cultural experiences however are ego syntonic. This is a key difference from the borderline personality whose aggression or violence is ego syntonic in the moment of hurt and rage only to become ego dystonic and cause for deep remorse and shame afterwards. For the dependent man with strong male dominance and stoicism standards, remorse and shame after committing abuse or violence is muted or denied altogether as ego dystonic. "Yeah, that's what you fuckn' get for crossing me!" asserts the ego syntonic matching of real self behavior to the ideal "don't take no crap!" and "coldass mutherfucker!" This reinforces the abuse and violent behavior and the denial of dependency feelings.

“Dependent men have a pattern of quickly moving into a new relationship following the loss of a previous relationship. We believe this is the result of the inability of men with dependency traits to tolerate the absence of a physical caregiver object. In case example #2, R. was aware of his anxiety when away from his girlfriend and that he was unable to keep a mental image of her, consequently feeling unloved and unlovable. This is an example of the failure to attain the subphase of object constancy (Mahler & La Perriere, 1965). The fear of loss of the caregiver object can be so extreme in some men with dependent traits that it can result in the use of physical violence in an effort to prevent abandonment” (Berk and Rhodes, 2005, page 199). A man with a history of physical violence would be more likely to commit domestic violence if his anger and aggression are not redirected in some fashion. For some men, it is directed towards anyone or anything that threatens losing the caregiver or intimate partner. If the threat comes from the intimate partner, then domestic violence becomes more likely since the dependent individual is unable to otherwise self-soothe. The therapist, professional, or concerned person may not readily observe dependency characteristics that are well hidden, but may manifest similar to borderline lashing out. Understanding the relationship of dependency and attachment anxiety may be critical for assessing the person's violence potential, especially when there is a possibility of domestic violence.