2. Social Cues - RonaldMah

Ronald Mah, M.A., Ph.D.

Licensed Marriage & Family Therapist,

Consultant/Trainer/Author

Main menu:

2. Social Cues

Therapist Resources > Therapy Books > Odd Off Different-Cpl

Off, Odd, Different… Special? Learning Disabilities, ADHD, Aspergers Syndrome, and Giftedness in Couples and Couple Therapy

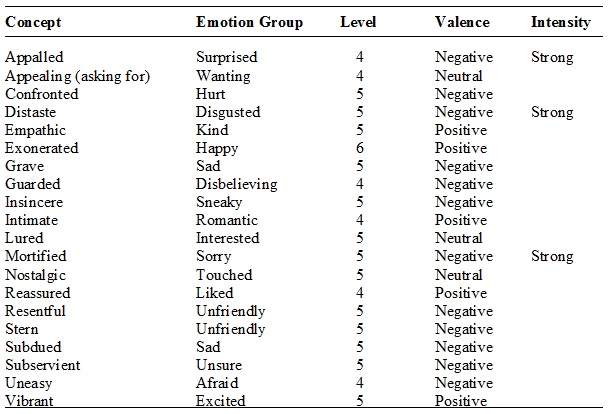

Chapter 2: SOCIAL CUES

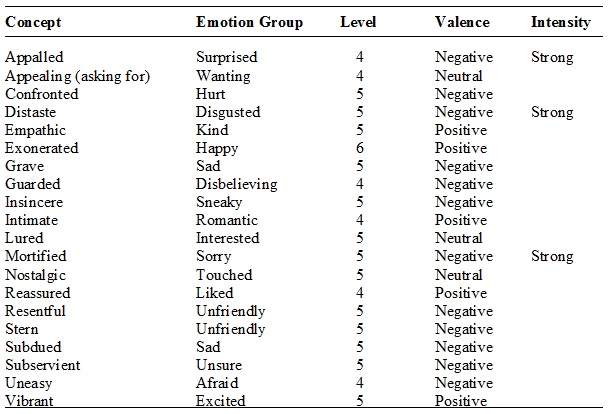

Brody missed social cues, especially non-verbal social cues critical to interpersonal communication. Facial cues include muscle tension or relaxation around the eyes and mouth, and tilting, leaning, or nodding one's head. Additional communication mix and match from combinations of changes in breathing, verbal tone, cadence, and rhythm expansive to very slight movements of the hands, arms, body, and legs. Golan et al's (2006) development of the Cambridge Mindreading (CAM) Face-Voice Battery is indicative of the complexity of non-verbal communications. The CAM battery evaluates a selection of 20 emotion concepts to represent 18 of 24 emotion groups. In all, Golan et al have identified 412 emotion concepts. The battery includes two tasks: emotion recognition in the face and emotion recognition in the voice where participants are asked to choose the adjective that best describes the person's feelings. Focusing on adult feelings, there are concepts understood by typical 15–16 year olds, concepts understood by typical 17–18 year olds and one concept understood by less than 75% of typical 17–18 year olds. The CAM includes mental states that are "positive" in valence, such as empathic and intimate, as well as concepts that are "negative", such as guarded and insincere, as well as emotions of varying intensity (subtle emotions such as uneasy, subdued and intense ones such as appalled, mortified. The twenty concepts with their level, valence and intensity coding are listed in Table I. (Golan et al., 2006, page 171).

Table I. The 20 Emotional Concepts Included in the CAM, their Emotion Group, Developmental Level, Valence and Intensity*

Note: *concepts with high emotional intensity are marked as ''strong''. (Golan et al., 2006, page 172)

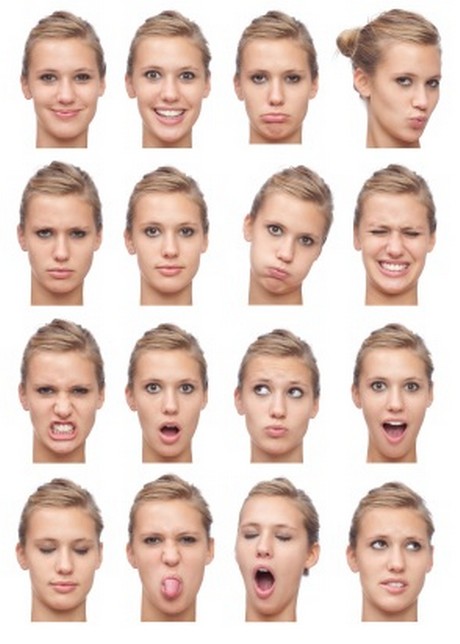

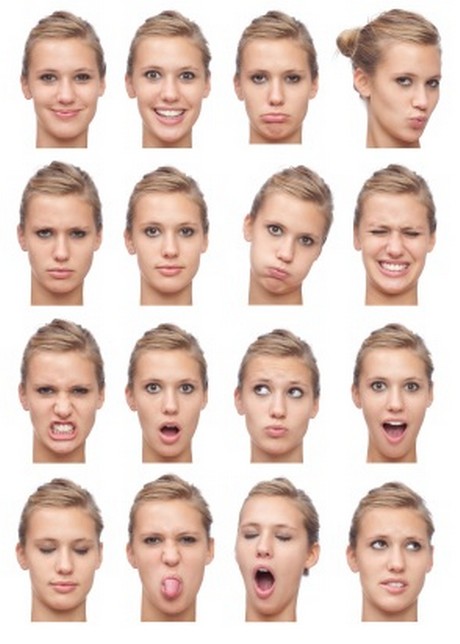

Brody would have been overwhelmed with the variety of emotions to consider. As a result, he tended to simplify interpretation in gross terms. He could tell if Faith was angry, if she was angry enough to snap at him and frown emphatically. However, he would have trouble distinguishing her being perplexed, uneasy, annoyed, upset, resentful, angry, or infuriated. Brody would either miss Faith's more subtle or complex feelings or interpret all of these emotions as anger. He would likewise have trouble with presentations from other emotional groupings. The following is a chart with the model showing different emotions. The average person would or should be able to recognize each facial expression fairly accurately.

(From "Understanding Body Language," by Kendra Cherry, About.com Guide. Photo by ZoneCreative)

Faith expected Brody to "get" her just by looking at her. Individuals normally can determine a spectrum of simple and complex mental states from whole facial expressions. The whole face gives much greater information for basic mental states either the mouth or the eyes. However, "for complex mental states the eyes (but not the mouth) provide as much information as the full face. This may be because complex mental states are not easily expressed just by the mouth, unlike basic ones (happy, sad, etc.)" (Baron-Cohen et al., 1997, page 324). "It also demonstrates that the eye-region effect is not a function of the face being observed, since the effect transfers across models of different sex" (Baron-Cohen et al., 1997, page 325). A possibility in some couples may be cross-cultural interpretations of the same cues. However in Brody and Faith's situation, they were from the same ethnic background, the same socio-economic background, grew in the same neighborhood, and went to the same schools since childhood. Moreover, individuals across cultures tend to agree on interpretations of mental states from facial expressions. This included complex mental states such as scheme, revenge, guilt, recognize, threaten, regret, and distrust, so-called "complex" mental states, as well as the basic emotions such as fear (wariness) and surprise (astonishment). This furnished important evidence that, cross-culturally, mental states recognition extends beyond the basic emotion…" (page 313). There are additional aspects to non-verbal communication moreover in addition to recognizing facial expressions.

Nonverbal communication is quite possibly the most important part of the communicative process, for researchers now know that our actual words carry far less meaning than nonverbal cues. For example, repeat many times the following sentence, emphasizing different words in the sentence each time you do so: "I beat my spouse last night." Does not the meaning of the sentence change? The meaning can range from an act of domestic violence to a report about the outcome of a board or respective arrival home from work to humorous commentary about some playful interaction. The words themselves carry many meanings, depending upon nonverbal cues, in the case, inflection. Essentially, the study of nonverbal communication is broken down to:

environmental cluesspatial studyphysical appearancebehavioral cuesvocal qualitiesbody motion or kinesics (Long Beach City College Foundation, 2004).

Individuals such as Brody have a tendency to hyper-focus on the verbal communication because of their weakness in interpreting non-verbal communication. Faith questions Brody about his work schedule and if he had chores to do before getting home. She asks about traffic at the times he would leaving from work. She adds that the plumber is coming for a late appointment to fix the sink. She also says that it is a different plumber that is coming because the one they have used before was not available. She ponders out loud if the plumber would be any good… and honest. Brody listens to everything she says and assumes that she is just keeping him informed. Brody has no idea that she wants him to do something. She ends up having a bad experience with the plumber having tried to pressure her into authorizing and paying for work that was not needed. Faith is subsequently upset with Brody for not having come home to be there when the plumber was there. As she described what happened, she is clearly (even to mindblind Brody) upset and angry… at him. Brody is perplexed when she says to him accusatorially, "You should have been here." He honestly proclaims his innocence, "I didn't know you wanted me to be home for the plumber." Faith declares, "You knew I was uncomfortable. You knew I didn't want to be here alone with the plumber." She adds something that is clear to her but incomprehensible to Brody, "I told you I wanted you to be here!"

"What!?" Brody is stunned. Brody plays back in his mind the words he heard that morning. Nothing. Some irrelevant question about his work schedule that Faith already knew (why would she ask that?!), traffic questions (20 minutes… it always takes 20 minutes for him to get home. Faith knew that), a new plumber, Faith wondering if the plumber would be any good and be honest (how was he supposed to know if the plumber was any good… or honest?!). Nope. Nothing. There had been no request for him to come home early. She never said… no words said for him to do that. In the heat of the situation, Faith remembers her anxiety clearly and her efforts to get Brody to get home early. Of course, she told him… told him emphatically… non-verbally. She does not distinguish between verbal and non-verbal messages because communication is not compartmentalized in her process. Brody had not noticed the tension in her voice, the slight frown and pursed lips, how her eyes widened, the tilt of her head, her slightly frenetic hand movements, her stiffer posture, and other non-verbal communications of stress and anxiety, that constituted her implicit request to be supported by Brody. A huge argument ensues based on Faith asserting that Brody should have known what she wanted- she just about told him, and Brody asserting she did not tell him, should have told him if she wanted it, and that she did not ask him… that she did not ask him… that she did not ask him. Brody is entrenched in his literal recollection and interpretation that she did not ask him. Subsequently, he completely ignores and fails to respond to Faith's distress from having had to face an intimidating stranger on her own in her home.

"He kept pressuring me.""You didn't ask me.""I felt scared.""You should have asked me.""I felt so vulnerable.""How was I supposed to know?"

Brody never addresses or tries to soothe Faith feeling isolated and violated in her sanctuary. Distressed and somewhat traumatized by the plumber incident, Faith is further distressed and traumatized by Brody's lack of compassion and understanding.

Successful expressive communication and receptive communication are the keys to intimacy, trust, and relationships, drawing support, compliance, or allegiance. All these are critical to emotional and psychological survival. In "Body Language in Debating," Mandic (2008) promotes 10 compelling non-verbal forms of communication applicable to day-to-day communications that Faith may have attempted and Brody missed.

1. Vocal- We respond to the dynamic, rhythmic, melodic and accent, stress, or tempo components of someone's voice. Silence can be a very powerful message, as can raising or lowering the voice.2. Facial- The face is the most expressive part of our body. Macro and micro facial expressions are strong messages usually connected to feelings, attitudes and personal belief systems.3. Gestural- Gestural aspects of body language are understood in connection to contexts and relationships with other people.4. Postural- The postural aspect of someone's communication relates to the position of the body in a dialoguing context. The whole body is a unit of communication.5. Proxemic- The proxemic aspect includes communication through physical contact including both touch oneself or others.6. Spatial- The spatial aspect uses space to communicate issues such as dominance, acceptance, extroversion, or respect.7. Rhythm- The rhythm of breathing, eye movement, hands and legs, and the whole body gives meaning to someone's expression. Sudden changes in rhythm will increase attention and stress the importance of the speaker's point.8. Movement- Movement is a macro statement in communication and can reveal basic motives, character traits and some practical intents of the person moving.9. Clothing and Body Decoration- These aspects are dependent on individual and cultural standards or ideals.10. Drawing- Drawing is a natural form of communication that may be especially relevant with younger children who are pre-verbal or have difficulty verbally articulating.

Non-verbal sensitivity, awareness, freedom and creativity have enormous impact. Becoming non-verbally fluent, centered, grounded and flexible not only develop self-esteem, fluency and flexibility, but enables better communication skills and relationships in personal, vocational and societal relationships and life.

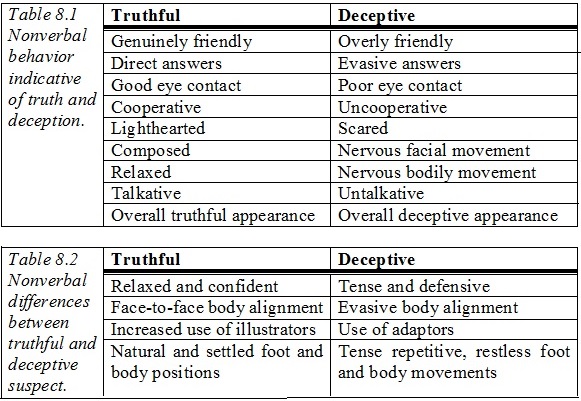

PRESENTING INADVERTENT CUES

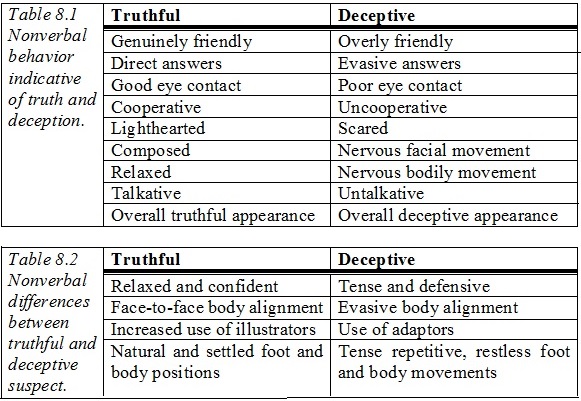

Gordon and Fleisher, (2002, p.84) describe how interviewers make a determination of an interviewee's truthfulness. Examination of two tables, reveal principles and assumptions that mirror similar processes people intuitively use to determine the honesty or deceptiveness of others communication, including that of their partners.

Challenged individuals may inadvertently present non-verbal cues others assume to be deceptive or harboring or negative intentions. Several deceptive characteristics listed ("tense and defensive," being "scared," "nervous facial or body movement") could be immediate or habitual reactions to anxiety, teasing, frustration and/or failure socially. Other characteristics considered deceptive may actually be characteristics of a particular challenge. For example, unusual body alignment or a slight physical awkwardness of individuals with Aspergers Syndrome, other autistic spectrum issues, or a physical challenge may be considered "evasive body alignment." Other characteristic behaviors such as repetitive rocking or other self-soothing physical tics or movements and difficulty maintaining eye contact may be interpreted as deceptive "tense repetitive, restless foot and body movements" and "poor eye contact". Non-Verbal Learning Disabilities may draw individuals to highly stimulating background visual cues and appear as "poor eye contact." "Evasive answers" may be gifted individuals responding to nuances or fascinating alternative perspectives unanticipated by a listener. A response may be considered "uncooperative" when ADD distractibility or ADHD combined distractibility and impulsivity draws both attention and behavior to other attractive urgencies. Or, energy to restrict body activity and stay attentive strains ADHD individuals. "Evasive body alignment" or "nervous bodily movement" ensues. It is therefore, not surprising that people may interpret challenged people's non-verbal social cues as aloof, defiant, or disrespectful. As much as Faith was challenged by Brody's quirky behavior, others at work or socially were often far more judgmental and rejecting of him based on incorrect assumptions about his intent and motivations.

CONTINUUMS or LABELS

On continuums, individuals may be considered weak, average, strong, or exceptional for any number of skills or characteristics. Or, they may have quantitative differences considered compelling to be considered qualitatively distinctive. Such differences may cause either or both significant challenges and exceptional capacity. A label or diagnosis may activate or focus services or intervention. Understanding continuums allows for the therapist's experience with "average" skilled clients to aid diagnosis, intervention, and support for those on the higher and lower ranges. Conversely, greater knowledge and experience with individuals for example, in ranges labeled learning disabled, ADHD, Aspergers, or gifted potentially enhances the therapist's work with all clients. Clients with Aspergers Syndrome may also have ADHD, learning disabilities, and be gifted. Clients with gifted abilities may have ADHD or have learning disabilities. All individuals may have differences in how they learn, communicate, and interact. Such differences however remain within a continuum of humanity. Differences and/or labels are also used for targeting and justification for abuse. People have often substituted "dummy" for learning disability. ADHD become synonymous with "bad boys" or "bad girls" or "difficult clients." Aspergers becomes a way to say "weird." People with gifted abilities are called "brainiacs" or "geeks."

The therapist should beware of clients having possible prior negative experiences from having been negatively labeled. A client such as Brody may anticipate further shaming if the therapist presents observations and hypotheses about a diagnosis. The therapist should utilize knowledge about differences, not only to serve therapy, but also to identify whom to protect and empower against misunderstanding. Well presented, it may simultaneously validate the challenged individual and offer relief to his or her partner. The challenged individual will feel understood to have his or her communication and behavior identified as a variation of normal processing. His or her partner may be able to ascribe ineffective or inappropriate communication and behavior to the challenge. The partner such as Faith can abandon his or her fear that the lack of love, caring, or respect is reason for the behavior and communication. Some individuals, including the therapist may have negative perspectives of people with challenges or disabilities. The negative perspectives range from discomfort, to fear, to moral judgment- from begrudging acceptance to tolerance to outright rejection. Individuals with challenges or disabilities feel negative perceptions and are harmed by them. They can also be harmed by how they are treated, even if the intentions of the other persons are benevolent. A partner and/or the therapist may engage in the following sometimes well-intended but harmful processes:

INVISIBILITY: Invisibility is the practice of keeping challenged, different, or disabled people out of sight- as if they were invisible ("Out of sight, out of mind"), because people may not feel comfortable or want to avoid having to deal with the person. Sometimes well-intended people ignore or pretend not to notice issues for fear of making the person feel uncomfortable or embarrassed. They avoid talking about any issues, or may downplay them. Unfortunately, this gives a person the message that not only does his/her challenge, difference, or disability does not count or matter in the world, but also that he/she as an individual does not count or matter to others. A partner or the therapist may treat the difference, disability, or challenge as non-existent. It can become the proverbial elephant in the room as much as racism, domestic violence, or a partner's or family member's alcoholism or mental illness can also be unaddressed. Invisibility is consistent with the general caution in family therapy that held secrets take stressful energy and cause emotional, psychological, and systemic pain.

INFANTILIZING: Infantilizing is the practice of treating a person with a challenge, difference, or disability as incapable and dependent- treating him/her as if he/she is and will always be limited in skills and capabilities like an infant. As the child or individual is continually treated as if he/she were both fragile and incapable (rescued, taken care of, having tasks done for them), the syndrome of learned helplessness can develop. As the partner, adult, teacher, or therapist's behavior keeps sending messages that he/she is both fragile and incapable of mature behavior, the individual first begins to consider, and then eventually comes to firmly believe (learn) that he/she is helpless. Overprotected individuals (with or without issues) fulfill the prophecy, and become incapable and vulnerable, and dependent on others. In the couple's relationship, which is often explicitly assumed to be egalitarian and equitable, infantilizing a partner places him or her in an inferior position. An individual may seize upon a real or perceived issue in his or her partner as justification of supremacy or domination. Couple therapy may be an attempt to rebel against the infantilization or domination. On the other hand, the therapist should be wary that an individual may try to recruit the therapist to be complicit in infantilizing his or her partner.

OBJECTIFYING: Objectifying is the practice of seeing only a person's challenge, difference, or disability rather than seeing the whole person. That a person has an issue does not automatically mean that he/she has no other abilities. Every person with a challenge, difference, or disability still possesses many other abilities, some of which may be or have the potential to be quite remarkable. Objectifying a person defines the person totally in terms of his/her issue only, without regard to his/her full spectrum of abilities. A person who accepts objectification will only think and be regarded in terms of what he/she cannot do, as opposed to the many things he/she can do. He/she will assume the identity of or be perceived in terms of the stereotypes of people with that disability, rather than as a unique individual- a blind man, as opposed to a man who is blind...and a lot of other things as well! The therapist should see if a partner has been objectified in the relationship. It may be likely that one or both partners may present this as factual to the therapist. A therapeutic version of objectification is the designation of the identified patient (IP) as the individual in a dysfunctional system who is ill. The therapist should challenge the IP status as the sole owner of dysfunction and the other partner as innocent of complicity and issues. Individuals who understand, own, and put their issues in context rather than allowing them to pervade their identity are more successful in relationships and life.

"The one component of self-awareness that discriminated the successful from the unsuccessful participants was the ability to compartmentalize their disability. That is, successfuls were able to see their learning difficulties as only one aspect of themselves. Although they were well aware of their learning limitations, they were not overly defined by them" (Goldberg et al, 2003, page 226). The therapist can help the individual reframe an issue from inherently dysfunctional to being a part of his or her functional self. This aids moving from shame to acceptance and moving beyond the challenges. "…while successful informants acknowledged and accepted their disability, they saw it as only one aspect of themselves" (Goldberg et al, 2003, page 233). Brody can be clinically diagnosed with a particular diagnosis that can shed light upon their relationship problems, but the therapist should take care to put it in a proper context as one aspect of himself- a significant aspect, but not the only aspects.