4. Interrupting the Pattern - RonaldMah

Ronald Mah, M.A., Ph.D.

Licensed Marriage & Family Therapist,

Consultant/Trainer/Author

Main menu:

4. Interrupting the Pattern

Therapist Resources > Therapy Books > Out Monkey Trap- Breaking Cycles Rel

Out of the Monkey Trap, Breaking Negative Cycles for Relationships and Therapy

Chapter 4: INTERRUPTING THE PATTERN

by Ronald Mah

Strategic family therapy originally developed in the 1950s by Don Jackson and others belonging to the Palo Alto research group headed by Gregory Bateson. In strategic therapy, the therapist focused on changing family interactions and excising specific problems targeted by client, by assigning homework to the family or couple and using paradoxical interventions and sometimes, creative and unusual methods. One branch of strategic family therapy reflected the Mental Research Institute (MRI) (founded by Don Jackson in Palo Alto) which is based in the identification and change of problem-maintaining family interactional processes and patterns. Another major approach, based on Jay Haley's work (an original member of the MRI) emphasized the realignment of hierarchy and power to promote the desired change in families (Gardner, et al, 2006, page 339-40). Strategic family therapy is a brief form of therapy that focuses on changing the system behavior associated with the identified problem. The therapist facilitates change in the system by giving either straightforward or paradoxical directives. Homework is assigned to perform at home. These interventions help members change problems by changing current inter-relational behaviors. If the therapist and clients can identify the problem and the interactional patterns involved, and the clients follow the directives, then therapy is successful. Jay Haley who established the term ''strategic' therapy," built on the work of MRI and others. In 1967 Haley left MRI and began working with Salvador Minuchin. Along with Cloe Madanes, they developed a therapeutic focus on hierarchy and family structure.

"Thus, strategic therapists are primarily concerned with the promotion of change in families, particularly in the areas of family interaction patterns, family structure, power, and control. Strategic family therapists assume that while all families have the psychological capacity to change, current family behavior, communication patterns, or hierarchical structure allow the identified problem to persist. Change in the family system will result in problem resolution. Not all behaviors, patterns, or problematic structures need to be altered in order for change to occur. Rather, small amounts of change in families are often sufficient to prompt more dramatic changes in family interactions and structure" (Gardner, et al., 2006, page 340-41). The traditional strategic practice is brief and intense therapy. The therapist is very active and involved in therapy. The focus is less on past experiences and more on what is currently going on. The therapist attempts to quickly collect information for assessment and attention to the problem identified by the clients. The individual, couple, or family members are prompted to talk about the problem. Through observation, the therapist assesses the system's normal interaction patterns and hierarchy. Encouraging members to speak may facilitate change in itself, if they as a group do not usually communicate openly about the problem. The individual, couple, or family may feel stuck in an impasse where there are ever intensifying emotional reactivity. The individual, partners, or family members take intractable stances and lose rational perspective while repeating over and over the same negative dynamics with each other. Stuck in one's own view of things, no one holds empathy for another and cannot relate to the other's experience. Individuals become insulted by each other and become ever more defensive, emotionally distant, and caught up in frustrating power struggles and misunderstandings. "These impasses involve vulnerability and confusion, and they tend to become more pervasive over time, taking up more and more space in the relationship" (Scheinkman and Fishbane, 2004, page 281). The therapist seeks to interrupt the negative cycle of futility that has come to dominate the relationship.

Every relationship system finds a balance, but in some situations the balance has become harmful to its members, or within a person. "Homeostasis implies that families regulate their own interactions to preserve equilibrium via corrective feedback mechanisms. While these processes are essentially adaptive, they can also lead to dysfunction when symptomatic or maladaptive behaviour is incorporated into change-resistant patterns" (Rhodes, 2008, page 35). When the individual, couple, or family arrives in therapy, something is not working in the system: intrapsychically or with others. Usually something has not been working for a long time in the system. Some issues have been in the system a long time. To gain more awareness about what these things may be, the therapist may tell the individual, couple, or family to act out the problem. Their willingness can be indicative of their commitment to change as well. The therapist takes a powerful role and is extremely directive to get the client to act or to do something. He or she gives specific directions to promote changes in behavior and system functioning. The therapist must simultaneously create trust with the individual, couple, or family to gain willing cooperation to follow his or her prescriptions. He or she will emphasize positive qualities and behaviors and note any gains in the individual, couple, or family. This may include re-characterizing from a positive perspective previously negatively viewed behaviors. "The strategic therapist provides opportunities for change in a variety of ways including encouraging, discussion, examination of motives, and expression. Strategic therapy is used to produce rapid change in families without spending any time trying to promote insight or psychological awareness of the ''deeper meanings'' that might be associated with the problem. The expectation is that with the changes effected in therapy the family will continue to change in other areas after therapy has ended" (Gardner, et al., 2006, page 340-41).

For some individuals, couples, and families, the act of entering into therapy may be the most impactful intervention by itself. The cycles of negativity and frustration may have persisted for a long time. The same approaches and reproaches have not made anything different. Arguing, silence, avoidance, retreat, attack, shut down, eruption…other relationships and the couple or family continues a fruitless cycle of recrimination for weeks, months, and years. When the individual, couple, or family decides to enter therapy, therapy and the therapist are in themselves interrupting the negative cycle. "Indeed, Haley (1984) wondered if all therapy was essentially an ordeal intervention. That is, the effort required to visit with a therapist, discuss difficult issues, think about uncomfortable or distressing thoughts or feelings, and/or talk to family members about such things ultimately serves as a therapeutic ordeal that exerts pressure or stress on individuals and/or families and promotes change. Some preliminary evidence suggests that, for non-clinic couples, a simple invitation to move from a more conflictual discussion about recent hurts in the relationship to a more positive discussion about instances when partners felt cared-for or supported is enough to significantly alter the affective climate of the conversation and move couples from one pattern of affective experience to another (Gardner & Wampler, 2005)" (Gardner et al., 2006, page 347).

The therapist's entry to the system changes the context of the individual alone or of the couple or family. The therapist will continue to create other alterations in the system. A strategic approach could work to manipulate the system to change how, when, or where the problem occurs. This serves to lessen the experience of the problem having power on the dynamics of the relationship. This can create cause the individual, couple, or family to change how they see the problem. The problem seen in a new light with altered meaning can shift the system fundamentally (Gardner et al., 2006, page 347). Cognition distortions may be corrected and break the negative cycle of interactions. When the therapist gets members to express overtly rather than covertly, or speak directly to one another instead of indirectly, the system's negative communication cycle can change. Directives and interventions attempt to change routines or behavior, block behavior, get members to fight rather than withdraw, or withdraw rather than fight, or touch rather than talk, and otherwise serve to interrupt problematic behavior hierarchies. A somewhat different approach with similar underlying principles is the Milan Approach. The "Milan Approach initially proposed that pathological behaviour was the result of individuals being isolated or vilified in the power struggles to maintain particular family relationships. Symptomatic behavior was seen in two ways: as a reaction to this isolation and as a means by which a family member could 'strike back' against those family relationships that were excluding and hurtful. Therapy attempted to offer insight into the struggle for the control of family relationships, often over several generations; and it attempted to counter the family's resistance to change with powerful rituals, homework tasks, and paradoxical prescriptions" (Campell, 1999, page 77).

One way or another, the strategic goal for the individual, couple, or family is to find or create release from old behaviors or rituals dysfunctionally maintained for years. The new rituals, homework, prescriptions, and other therapeutic interventions may be culturally foreign or new to the individual, couple, or family. Upper-middle-class white professionals and Jewish Americans tend to be more receptive to counseling as it more fits into the cultural patterns of their communities. Individuals of Asian ancestry on the other hand, tend to be less receptive to counseling as an intervention. Emotionally based and cognitively based therapies may not be well received. However a directive approach may be welcome. Non-Western cultures tend to be more receptive to an authoritative voice that gives straight directives. For example, giving the couple dating homework can break the cycle of all work and no play. Sometimes, couples can benefit from a simple intervention of assigned dating. Plan time and energy to play with each other again; use the dates to learn to like and enjoy each other again. This interrupts the "being parents" with a "being a couple" pattern. Culturally speaking, being a mutually attentive and nurturing couple may go against a pattern that as soon as the children are born, prioritizes being parents over any reciprocal couple's relationship. Any and all of these interventions can be effective if they are cross culturally presented and accepted.

A strategic approach involves breaking the cycle or pattern of behaviors. As such, prompting clients to be ready for and to accept breaking of the process is akin to asserting that this will be a cross-cultural process. Culture is a pattern of behaviors. Interrupting or blocking the cycle or pattern is an assertion, that the cycle or pattern (the present culture) is ineffective or inappropriate to help the individual, couple, or family survive the current crises in the relationship. The therapist asserts the role as a cross-cultural facilitator or educator. The therapist can take a directive role in interrupting the process in the session. In many cultures, clients expect a therapist/doctor or other authoritative person to be very active and directive in working with them. The therapist is considered the expert and as the expert expected to have something strong and clear to give to the client. This may be against some therapists' existential and humanistic orientation to therapy... or right in line, perhaps with a cognitive behavioral orientation or a problem-solving therapeutic orientation. It is important for the therapist to remember, however, he or she is not there to do his or her cultural/therapeutic orientation but to serve the client's needs. If the client needs a directive approach, then the therapist should provide it.

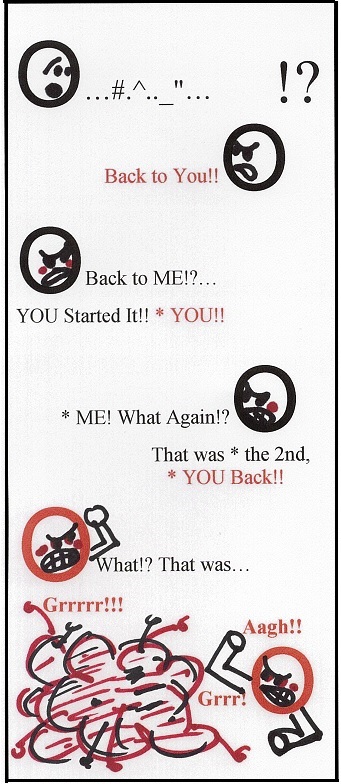

The graphic shows a cycle between two people. There is a hierarchy of behaviors that can start with something relatively benign and arguably insignificant. The two people intensify with each response.

Eventually, they come to an impasse- perhaps, an explosive, emotional, and possibly physical fight. As a result, both people become highly sensitized to interpreting a subsequent incident, word, or behavior as another attack. In other words, the resultant injuries prompt the initial vulnerability over and over until there is no longer a relevant beginning or end- just an endless cycle. Other problematic dynamics occur in cycles as well. For example, "In the interactional sequence, when the distancer moves in, the pursuer chases her away either by attempting to close all the distance between them, or by exhibiting anger or criticism (Guerin et al., 1987). Unless interrupted, the couple will inevitably return to their baseline `dance', which maintains their relational physics" (Betchen & Ross, 2000, page 22). From a strategic perspective, all it may require is a relatively minor change for major shifts in how the individual acts or responds or the couple or family interacts. The dynamic systems view of nonlinear influences in complex systems asserts that sometimes extremely minor changes might trigger very extensive resulting changes. "…subtle differences in values as small as three or four decimal places—specificity that some may regard as 'unattainable' in the social/behavioral sciences— behavioral outcomes within complex systems. Thus, strategic therapists rely 'on a principle of nonlinear change, often focusing on creating a subtle change in one family member—usually the most willing—in order to generate more dramatic changes throughout the family over time'" (Gardner et al., 2006), page 346). With a couple, the therapist may focus on the more available partner. Often that is relatively easy. It may be the partner that makes the phone call and arranges for the therapy. The therapist should use the principle of available entry. If the front door is open, enter it. If the front door is barred, then try the back door, the side windows, the chimney, or dig into the basement or cellar! This refers not only to the most available or cooperative partner or family member but also to whatever issue or situation is most available to change. The therapist may want to direct interventions and change toward one or both partners or multiple family members. Or, to whatever aspect of an individual that is most receptive to change or most motivated. If the individual, couple, or family is particularly resistant to personal change, the therapist may provoke investment and shift by focusing them on children or other family, or money, or anything else that might draw energy. The intervention may be directives for doing homework, or may be done during the session to interrupt or alter communication dynamics.

Interrupting the pattern at home may be very difficult for the individual, couple, or family to manage. The therapist can begin and model the breaking of the cycles in the therapy itself. The interrupting intervention is often a cognitive interpretation by the therapist and may be accepted readily. However, there are individuals, couples, and families where the rigidity of the behavioral pattern can be overwhelming. The stress from the unhappy relationship can be very difficult for the individual, one or both partners, and multiple family members. Minor and major triggers re-ignite stress from various relationship situations. Pruitt's (2007) description of a teenager's experience in a challenged family (which could be Geoff with parents Genevieve and Dillard and sister Jenny) can be applicable to a partner's experience in a couple. "In response to a situational stressor, the teen begins to display depressive symptoms (sadness, irritability, hopelessness) and starts to isolate themselves from their peers and family. The depression keeps the adolescent from becoming autonomous and increases their sense of developmental failure, which reinforces their sense of hopelessness and isolation. Parents may try to motivate or support the teenager, but the depressed adolescent is likely to misinterpret and reject their parent's support. This rejection makes the parents feel that they have failed, and they become angry, critical, or more aggressive in their efforts to change or control the teenager. These controlling behaviors further reinforce the teen's sense of autonomy and self-denigration. The adolescent becomes more rebellious and withdrawn, and the parents become more helpless and angry. In this cycle, the parent-child relationship becomes a force that pulls the family members apart with increasing hopelessness, failure, anger, and isolation. As mentioned, the goal of therapy is to interrupt this negative cycle and to create more positive interactions in the family" (Pruitt, 2007, page 74-75).

Both people in a relationship or all family members may show similar symptoms, including isolating from the other or others. Whereas parents try to motivate the teenager, the partner in the couple- Dillard, for example may try but fail and become angry, critical, or more aggressive trying to change or control the other partner Genevieve. There may be multiple negative cycles in the family- one of which occurs between the partners of the couple. For example, the couple Genevieve and Dillard has articulated that they have a pattern where

1. Dillard does something that Genevieve doesn't like or perhaps, only isn't clear about.2. Then Genevieve questions him (sometimes, impatiently… sometimes just for clarification... often from a cultural or her family-of-origin perspective).3. Dillard assumes that she is being critical.4. Then Dillard snaps back in an impatient tone5. That Genevieve feels insinuates that she is stupid.6. Genevieve snaps back criticizing his tone.7. Dillard experiences it as even more criticism.8. And, snaps back that there Genevieve goes again!9. They repeat 1-8 several times, until10. Genevieve shuts down from anger and frustration (similar to how it felt with her parents... or because it is the only cultural option available to her)11. Which terrifies Dillard that he's being abandoned (again like his dad abandoned him, or since emotional abandonment is part of the cultural pattern of discipline)12. Which makes him even more angry and aggressive towards her.13. Which makes Genevieve shut down even more.14. Which confirms Dillard's abandonment, and intensifies his hurt and then, anger.15. And, on and on.

Individuals in relationships are often so sensitized to potential affronts that a seemingly innocent comment or facial expression can trigger an argument. The individual, couple, or family can escalate extremely quickly right in front of the therapist, and go out of control. The therapist should try to recognize the beginning of an impasse as it starts to gain momentum. "For example, by identifying bodily cues of anxiety, anger, or defensiveness, or automatic thoughts such as, 'he is so selfish!' This process allows each partner to reflect and make more informed, conscious choices rather than to react impulsively… As partners learn to catch the beginning moments of their impasse, they also become aware that they have choices about whether to follow their automatic reactivity or do something different. We call this moment of choice 'the fork in the road.' We help the couple identify specific alternative responses that they might have in tense moments with each other. This usually occurs first, retroactively, in a therapy session during an analysis of a recent fight. Each identifies what he or she might have done differently, not what the partner should have done differently. Thus, we might ask, 'If you could rewrite the script of this fight, how would you redo your part?' The awareness of alternative responses initially comes after the fight; we encourage 'Monday-morning quarterbacking,' or 'retrospective awareness' (Christensen & Jacobson, 2000) in the service of developing new strategies and choices. Gradually, the time gap between the fight and the awareness of alternative choices narrows until the couple can catch themselves during a fight" (Scheinkman and Fishbane, 2004, page 295-96)

A pattern often reveals itself in the therapy as an individual, couple, or family discusses an incident from the week. No one is or was able to break the pattern. The therapist seeks to interrupt the pattern in several places. Which place? Whichever place an intervention can work!

The therapist can interrupt early on and block Dillard's retort, and ask what tone he is hearing? This can be an interruption in individual therapy as the person is blaming, judging, or angered about something he or she is talking about. This interrupts because it may push the individuals into owning, examining, and articulating their underlying hurt that comes before the anger. It also may block a toxic response.The therapist can interrupt by asking the individual such as Genevieve, "Who did this insult to you first." What does the dynamic or experience reminds them of from their youth? This interrupts because it promotes insight to the original traumas that are being played out, rather than letting them believe that it is simply about each other in the present.The therapist can interrupt by asking what is going on inside them as they repeat the same thing over and over. This interrupts because it promotes self-awareness of the process where there may have been none, and of their intensification process as well. "Where does that come from?" which is a family-of-origin or cultural prompting for the original modeling of the response.The therapist may also ask Dillard, "Why did Genevieve shut down; what was the alternative?" Or ask Genevieve, "Where did you learn to do that?" Or, when the Genevieve shuts down, "I see what you do when Dillard shuts down, but what does his shutting down do to you? What is the feeling before the anger? And the nasty retorts?" which leads again to insight and self-awareness.The therapist can instruct Genevieve to articulate these feelings verbally rather than act out. "Tell him why it's hard for you to stay present when it gets this intense." This request is in itself an interjection in the cycle, since it reframes "shutting down" as not Genevieve abandoning him, but her having difficulty staying emotionally or psychologically present. It challenges the automatic cognitive assumption that can only be abandoning.The therapist can instruct Dillard to express the feelings to Genevieve with the prompt, "Tell her what you feel. Do it by repeating and completing these series of sentences, 'I get hurt when __________. I need you to __________. I get scared when _______.' She needs to know this. Genevieve WANTS to know this."

The therapist can ask the other person or another family member the same questions. The therapist should not be passive and avoid assertive interventions. Letting individuals go back and forth without interruption allows the toxic cycle to replicate in therapy without any change or potential benefit. The therapist should consider interrupting by any means possible. The negative pattern has to be broken. If the therapist can break the cycle or pattern in battle in the therapy and something (virtually anything, no matter how incremental) positive may happen. With any change or shift, the process can be analyzed and dissected as a model for interrupting negative dynamics further at home. It would be very positive, if in the process of interruption, there is an honest expression of vulnerability, love needs, the need to love, and nurturing that occurs. These are what the prompts about feelings and needs are about. Therapy may be the only place this empathy and connection may happen for a deeply stuck individual (from the therapist) or for a couple or family from others. However, that it can happen at all- albeit with the therapist's aid, gives them hope that it can more often and in their real lives. This interrupts the cycle of investment and risk that only previously resulted in frustration and failure that killed hope.

Anything that breaks the negative cycle offers the possibility of new behavior. The new behavior may not be positive, but at least it is not the embedded and ongoing historical dysfunctional behaviors. Replacing an old "bad" with a new "bad" is a positive accomplishment. After the "new bad" has become a part of the relationship, individuals may find it often is significantly easier to replace the new dysfunctional behavior, versus replacing a calcified old behavior. Strategic therapists may attempt to create incremental changes that are insufficient for fundamental progress for functioning or the relationship. However, an initial small alteration followed by one subsequent minor adjustment after another can accumulate into a critical mass of differences in energy, attachment, trust, and more. The strategic therapist holds this principle through the seemingly insignificant behavior changes and fruitless sessions to keep him or herself active in prompting and challenging individual, couple, or family dynamics.