18. Partner Insight - RonaldMah

Ronald Mah, M.A., Ph.D.

Licensed Marriage & Family Therapist,

Consultant/Trainer/Author

Main menu:

18. Partner Insight

Therapist Resources > Therapy Books > Ouch Borderline in Couples

Ouch! Where'd that come from?! The Borderline in Couples and Couple Therapy

Chapter 18: PARTNER INSIGHT

In many couples, the partner often is sufficiently experienced and knowledgeable about the other member and his or her family to understand the how and why of mood changes. The partner with borderline personality disorder has mood changes that are predictable, understandable, and to a significant degree, tolerable. The partner of the individual with borderline personality disorder nevertheless, is often confused by the shifts in individual's attitude and behavior, and is ambushed by their intensity. The partner may be able to see through the anger, hurt, and depression to note the individual's anxiety without understand its intensity and the subsequent punitive or self-harming behavior. Without a conceptually guided exploration, the partner is vulnerable to be confused, confront without focus, and make relationship-damaging interpretations about the individual. The partner becomes likely to interpret that the individual to be out of control, unredeemable, weird, a split personality, purposefully hateful, or any number of terminal conclusions.

The partner's schema about relationships and intimacy are also critical to the dynamics. A common but fantastical relationship rule holds that the other person will intuit everything that one desires and automatically give such support without any prompting. Caring will naturally and readily cause one to see through to the other's core needs and feelings. This "golden rule" of relationship is problematic in many couples since people tend not to be completely adept mind readers. Fortunately, for most couples the impossible romantic golden rule is mitigated by reality checks and eventual negotiation between the members. However, fears about betrayal, abandonment, and rejection form the existential reality for the individual with borderline personality disorder cause him or her to experience the betrayal of the golden rule as especially devastating. On the other hand, the partner often dedicates him or herself to fulfill the expectations of the golden rule. Despite this, the partner does not get the benefits of following the golden rule. His or her relationship reality is being crucified over and over by the individual (counter-balanced by periods of idyllic intimacy). Both the individual and the partner function in their mutual Wonderland as confused as Alice when she followed the white rabbit down the rabbit hole.

Unlike the white rabbit who lead Alice to the Cheshire Cat, the Mad Hatter, a psychedelic tea party, and worse, the therapist needs to lead both members out of the borderline craziness. When the individual with borderline personality disorder is unable to be introspective or lacks insight about his or her process, the partner can be a critical additional resource. A dynamic process of information and conjecture among the individual, partner, and the therapist can provoke deepening revelations and insight from both the individual and his or her partner. The therapist can prompt the partner's insight about the individual with skillful and judicious questioning. The partner will often have awareness and knowledge of vital information, behavior, and processes of the individual without knowing their importance or relevance. The partner will often have observations and instincts about the individual's family-of-origin that correlate with attachment and self-esteem issues. The therapist may find the partner's experiences of the individual contribute to understanding how borderline personality disorder or other issues affect their relationship. This insight enables the therapist to further query and provoke the individual's self-awareness and introspection.

PARTNERS IN BORDERLINE HEALING

Linehan's dialectical behavior therapy teaches day-to-day skills, since motivation and theoretical awareness are not sufficient without the individual having tools to live life and relationships well (Carey, 2011). The therapist teaches various skills in therapy conceptually and in live interactions between the therapist or the partner and the individual with borderline personality disorder when he or she is triggered. However, the practice of these skills has to occur in the real world sans therapist at the couple's home. The partner and the couple therefore become vital to creating change. "Many authors (e.g., Fruzetti, 2006; Hoffman, Buteau, Hooley, Fruzetti, & Bruce 2003; Maltz, 1988) believe that the only effective approach to the treatment of women with BPD is a couple approach, as the spouse is often viewed as a vicarious victim of the psychopathology and an underestimated ally to the treatment process" (Bourchard, 2009, page 118). More than an underestimated ally, the partner may be the key element in borderline healing. The therapist must enlist both the individual with borderline personality disorder and his/her partner to be effective in the healing the borderline injuries and relationship. The individual with borderline personality disorder often cannot do this by him or herself. His or her ability to self-monitor and self-regulate his/her pain and acting out is very limited. The individual with borderline personality disorder needs to empower both the therapist, but especially the partner to help him/her in the process. Is this culturally acceptable? The individual because of cultural training, especially a male may have trouble giving such power to the partner. The individual may experience it as giving up power. Cross-cultural interventions may be necessary here. Empowering the partner is very challenging because it asks the individual to be vulnerable to the person he or she feels has hurt him/her the most. In addition, when the individual was previously vulnerable to those who were supposed to help him/her, he/she was betrayed. A cognitive approach along with psychoeducation may be the initial approach to convince the individual to accept empowering the partner.

The therapist needs to help both the individual with borderline personality disorder and his/her partner understand the psychodynamic, cultural, and family of origin issues that cause the vulnerability, hurt, and neediness... and subsequent vengeance. This may help the individual accept the therapeutic interventions and changes in the dynamic that will facilitate growth and change. And, will help the partner gain the compassion to tolerate the individual's process of healing borderline injuries and be successful in the couple's relationship. The partner needs to refuse to be abused, yet be able to nurture the pain underlying the anger that precipitates the abuse. Is that culturally possible? For example, in some societies or communities, the right of the husband to physically punish his wife may be culturally sanctioned. A cross-cultural approach that includes education about domestic violence laws may be necessary. The therapist needs to teach the partner how to recognize borderline dynamics, and then set limits (not to take abuse of any type) and still be able to validate underlying pain. For example, when the individual with borderline personality disorder reacts explosively, the partner needs to recognize it well enough to refrain from retaliating (or running), and respond differently.

Frieda had just ripped Cliff, accusing him of belittling her, insulting her… attacking her integrity and honesty. Cliff's instinctive response was to fight back- to be as verbally hostile and aggressive as Frieda had been. His other instinct and his prior experiences with her were to be quiet and hope it would blow over sooner than later. However, Cliff had learned that silence gives permission to Frieda to keep on with the same eruptions. With assistance from the therapist, he had learned that Frieda was raging from her anxieties about being betrayed, abandoned, and rejected. Cliff was not trying to do any of those things. Quite to the contrary, he wanted to reassure her that he cared about her and wanted them to be happy together. Drawing from therapy, he was self-aware enough to recognize his instinctive urge, slow it down and stop it, and respond differently. Cliff said, "What you just did, hurts. Right now my instinct is to attack back or withdraw, but I'm trying to hang in here. Are you trying to hurt me because I hurt you? I will not accept being abused, but I also want to know how I hurt you. Help me understand what I did and what it meant to you. Tell me how I hurt you." The partner such as Cliff with the therapist's support has to be insistent that both members stay with this process and avoid inflammatory previously habitual responses. When negative dynamics express themselves in the session, the therapist's ability to stay focused on identifying and validating the underlying issues will interrupt the process, and model for both members how to do it themselves. The therapist can prompt the new process, model it, and enforce it between the partners in the session. In essence, the therapist asks the partner to confront in a dramatically new manner; to confront without attacking; to be hurt and risk being hurt more without attacking.

Johnson (1991) made recommendations for social workers (page 170-71) when working with the individual with borderline personality disorder that are applicable to the therapist. What is more, the therapist can have the same goals for the partner of the individual with borderline personality disorder. The therapist asserts and negotiates both a therapeutic contract between him or herself and the individual, and a couple's contract between the individual and the partner based on these guidelines and goals. It is essential that the individual with borderline personality disorder agree to both contracts. The therapist must convince the individual of the critical nature of the agreements to make therapy and the couple's relationship work. Extending beyond Johnson's recommendations, the following are requirements for interaction with the individual for both the therapist and the partner.

1. Contact should be structured and predictable with clear rules established. For the therapist, that would be with respect to meeting times, payment, fees, and policies and procedures. For the partner, that would be with respect to communication, chores, spending, and any number of other household affairs. Any changes are to be actively discussed and resolved. As implicit rules, assumed processes, and other unarticulated expectations are discovered, experienced, or felt, overt discussion must be instigated to resolve boundaries. All assumptions and interpretations must have any symbolic meanings revealed for consideration and boundaries established through negotiation. Appropriate communication could be "What does that mean to you? There's something real important… maybe hurtful about what that implies to you. What might that be? Let's make it clear… make expectations clear."2. The therapist should take an active role by making frequent comments that anchor the individual with borderline personality disorder in reality and minimizes his or her perceptual distortions in unstructured situations. The partner must be empowered through negotiation with the individual in therapy to take an active role to provide frequent reality checks to him or her. This serves to reduce borderline misinterpretations of intent and meaning of behaviors in the couple's dynamics and household. Appropriate communication may be "Do you think I don't care about you? That's not true. This is what I was actually thinking…" Or, "What did you think I was thinking or felt?"3. The therapist and the partner must learn how to handle borderline verbal assaults without retaliating or withdrawing. The hostility of the individual with borderline personality disorder should not be suppressed but examined as part of a more general pattern of relating to others. This includes the therapist, the partner, previous partners, friends, colleagues, and family. Hostility directed at the therapist becomes an opportunity for the therapist to model for the partner how to handle the individual's hostility without retaliation or withdrawal. The therapist helps the partner handle the individual's hostility in the session and coaches him or her for handling it at home, also without retaliation or withdrawing. Appropriate communication could be "I don't like how you said that, and my instinct is to snap back, but that won't be productive. So, I'll… instead."4. The therapist and the partner both must repeatedly point out to the individual the adverse effects of self-destructive behaviors including: drug or alcohol use, risky sexual behavior, manipulativeness, and inappropriate rageful outbursts. The individual may not be aware that such behavior is to gratify certain wishes and relieve anxiety. The focus should be on the negative consequences of the behaviors as opposed to the individual's motivations. Appropriate communication may be "I know you're upset, but that's not good for you or for us. Is that what you really want? Is there a better way to express yourself?"5. The therapist and the partner should help the individual recognize that his or her self-destructive behavior is often to avoid painful emotions. By seeing that his or her behavior is defensive and communication to others, the individual can learn to develop more autonomy and self-control to express differently. The therapist and partner can help the individual learn what the self-destructive behavior is attempting (poorly) to communicate. For example, suicidal behavior may be for revenge; to coerce someone, or paradoxically, to feel more alive by cutting through feelings of emptiness and meaninglessness. Appropriate communication may be "I see how much you're hurting. Find the strength… you can handle it as hard as it may feel." Or, "Don't do something to hurt yourself or to hurt me. That doesn't help. What do you really want? I might or might not be able to do it, but tell me."6. The therapist and the partner must set limits on behaviors that threaten the safety of the individual, the therapist, the partner, or anyone else. Appropriate communication might be "Don't threaten me or threaten to harm yourself. That's not how you or we can get better. I can't keep dealing with being threatened and keep trying to make it work with you. Explain what you feel, want, and need directly without threats. See what happens."7. The therapist and the partner should keep focus on the present when interpreting and clarifying behavior, as opposed to focusing on the past. Appropriate communication could be "What's going on with you right now? What happened before, happened before. We need to deal with what's going on now? What really is going on right now? What can you and I do now to make it better?"8. The therapist and the partner each must examine personal feelings about the individual. Because the individual can be frustrating and disruptive, the therapist and the partner must self-monitor reaction to avoid acting out- perhaps by retaliation or withdrawing. Appropriate communication may be "I really don't like how I feel when you do that, and I really don't like what I want to say back to you. As upset as I am, I still don't want to snap back at you. It won't help me… you… or us. Can you say that again in a different way that I can handle better? That I can hear and understand better without being so reactive?"

Requirements for the therapist are paralleled by requirements for the partner. The partner, however, is not required to never provoke or trigger the individual with borderline personality disorder. While the partner should avoid acting out through retaliation or withdrawal, the partner and the individual need to accept that the individual will be triggered without warning and often without predictable rhyme or reason. Neither the therapist nor the partner is sanctioned to prevent the individual from suffering. No one is capable of preventing the individual from suffering. His or her attachment injuries created the borderline sensitivity and vulnerability beyond the capacity of others to heal. The focus is on quantitative improvements, in particular by the partner around:

Clear boundaries,Reality commentary,Reactions with less retaliation or withdrawal,Identification and verbalization of the consequences of negative behavior and their connection to avoidance of painful feelings,Confrontation of threatening behavior,Clearer present-focused interpretation and clarification, andManagement of feelings toward the individual with less acting out.

Sufficient quantitative change by the partner should lead to qualitative change. Both the partner's quantitative and the qualitative changes should help the individual with borderline personality disorder with his or her quantitative and qualitative changes. Permission is withdrawn for borderline behavior, while education and support is increased. The borderline experiential trinity of betrayal, abandonment, and rejection are addressed with this set of requirements. When the individual balks or becomes reactive to the therapist's or the partner's communications or behavior, he or she is reminded that either or both are complying with the therapeutic or couple's contract to be caring. This directly addresses the fear of betrayal. The individual is reminded that the feedback is continued involvement to build intimacy rather than to abandon him or her- the second fear. And, while there may appear to be rejection- the third fear, the rejection is of various negative behaviors while accepting the individual and his or her emotional distress. "Frieda, I'm doing this because I'm NOT betraying, abandoning, or rejecting you. I'm doing this to caringly comply with our relationship contract, improve intimacy, and show I accept you… and confront you and deny you your terrorist behavior."

Transference-focused psychotherapy as described by Levy et al. (2006) directs the therapist in ways that are applicable to directing partner interaction with the individual with borderline personality disorder. There is a need for a coherent approach to therapy as there is a need for the partner to have a coherent approach to his or her interactions with the individual. Otherwise, in therapy the therapist depends on instinctive reactions and/or personal style and professional preferences that may be ill suited to the individual's or couple's needs. The partner also interacts and responds to the individual from his or her instinctive schemas of needs and relationships. Unfortunately, the individual with borderline personality disorder present demands that confuse and stress the partner's expectations and ability to interact effectively. What has been coherent, logical, and productive in other relationships just doesn't work with the individual. Like Alice falling into the rabbit hole, the partner finds the individual's Wonderland full of mysterious and crazy experiences that threaten his or her sanity. The therapist needs to educate the partner about the existential world of the individual with borderline personality disorder. Although he or she may not like it, as that world makes sense to the partner, the partner can also learn how to logically intervene against its logical craziness- its dysfunctionality. For the individual with borderline personality disorder, by using clarifications, confrontations and interpretations, the therapist tries to provide the individual with the opportunity to integrate cognitions and affects that were previously split and disorganized.

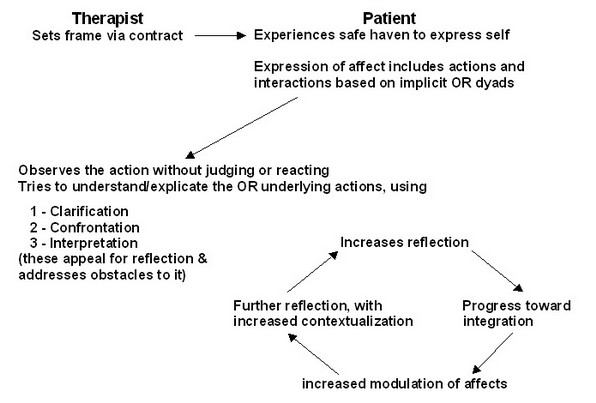

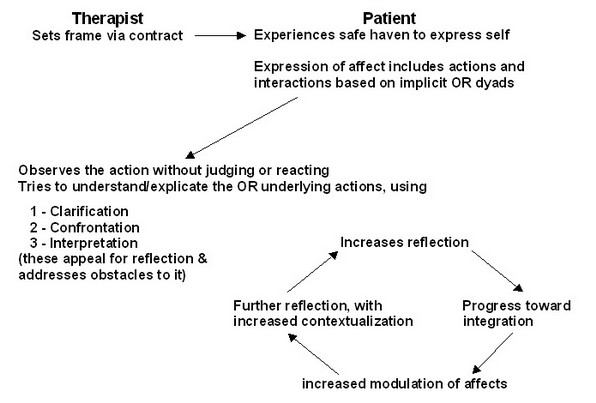

In addition, the highly engaged, interactive, and emotionally intense stance of the therapist may experienced by patients as emotionally holding (i.e., containing) because the therapist conveys that he or she can tolerate the patient's negative affective states. Selena needs to show she can handle Frieda's moodiness and outbursts. Furthermore, the therapist's expectation of the patient to have a thoughtful and disciplined approach to emotional states (i.e., that the patient is a fledgling version of a capable, responsible, and reflective adult) may be experienced as cognitively holding. Selena conveys her expectation to Frieda that she needs to and can respond with greater emotional balance. The therapist's timely, clear, and tactful interpretations of the dominant, affect-laden themes and patient enactments in the here and now of the transference are hypothesized to shed light on the reasons that representations remain split off and thus facilitate integrating polarized representations of self and others (Levy et al., 2006, page 487). The therapist should do the same with the partner. The therapist must build a relationship with the partner that expects that he or she will "have a thoughtful and disciplined approach to emotional states" not just with the therapist, but also specifically with the individual. The therapist teaches the partner to accurately interpret the behavior of the individual. The partner needs to learn from the therapist's insight about and skills interacting with the individual. The following chart illustrates the mechanisms of change in transference-focused psychotherapy. (Levy et al., 2006, page 488).

Essentially, the partner needs to be able insert him or herself in the place of the therapist in the model represented. The therapist along with the partner and the individual with borderline personality disorder work to establish this relationship as much as possible. The individual and partner agree to a contract with the partner empowered in this role. In the home situation away from therapy, the couple needs to create a safe haven for each member to express him or herself. The individual will express affect verbally and behaviorally based on implicit object relation dyads, which probably were modeled from his or her parents primarily. The partner tries to duplicate the therapist being able to observe the individual's behavior without judging or reacting. The partner takes what he or she has learned from therapy to try to understand the original interpersonal attachment injuries that underlie the actions, and offers clarification, confrontation, and interpretations to the individual. "By becoming familiar with each other's histories and reasons for thought/interpretation, feeling, and action according to their individual dispositions, the couples' capacity for empathy and tolerance will be increased when experiencing irritation and hurt from their spouse" (Tilden & Dattilo, 2005, page 156). The partner works on developing a way to offer these reactions in a manner that facilitates the individual being able to reflect upon them.

They need to develop improved ability to reflect upon the internal process that leads to the external actions. There is an objective reality and an existential reality for the individual, the partner, and the couple, that comes from what Levy et al. (2006) called psychic reality that fundamentally motivates each person. Adapting the psychic reality is a goal of therapy. This requires "the development of introspection or self-reflection: the patient's increase in reflection is an essential mechanism of change. The disorganization of the patient involves not only internal representations of self and others, relationships with self and others, and predominance of primitive affects, but also the processes that prevent reflection and full awareness. These primitive defensive processes that characterize a split psychological structure erase and distort awareness and thinking. BPD patients manifest a fragmentation and disconnection of thinking with attacks on the linking of thoughts (Bion, 1967), so the very thought processes are affected. Thought processes can be so powerfully distorted that affects, particularly the most negative ones, are expressed in action without cognitive awareness of their existence. The affect is only in the action, not in cognitive awareness" (Levy et al., 2006, page 490).

Reflection should occur on two levels. The therapist and the partner can prompt the individual to be more attentive to and articulate what he or she feels in the moment. Ideally, the individual will be able to self-initiate self-reflection and increase ability to experience, articulate, and contain feelings and to contextualize it in the moment. This would include not only self-awareness but also awareness of what the other person (the therapist, but particularly the partner) is experiencing. Reflective functioning often comes from the therapist and the partner intellectually giving clarifying feedback about what the individual may be experiencing in the moment. "A second, more advanced level of reflection is the ability to place the understanding of momentary affect states of self and others into a general context of a relationship between self and others across time" (page 491). This reflects greater integration of oneself and others with immediate perceptions are consciously, rather than unconsciously perceived relative to prior experiences, thus placed in appropriate contexts. Clarification of immediate perceptions of self and others moves further into confronting "contradictions between different states within the patient's psyche and interpreting the reasons that these internal states have remained split off. Borderline patients are quite sensitive, for example, to any behavior of others (i.e., the therapist) that suggests disrespect, a personal slight, or abandonment" (page 491).

The therapist needs to address any obstacles interfering with the individual being able to reflect upon his or her actions. This is a difficult but essential process. Someone such as Frieda is often desperately and habitually adverse to self-reflection. He or she is hypersensitive and may be devastated, enraged, or both if the partner and the therapist appear to gang up on him or her. Frieda has been heavily invested making Cliff the "bad guy," may be wary and ready to make the therapist another "bad guy," and would resist becoming the target of challenging feedback- that is, being made the "bad guy" instead! When the therapist or the partner attempts to provide clarification, confrontation, and interpretation, the individual is liable to feel criticized- attacked which prompts his or her borderline sensitivity. The solution to borderline reactivity, so to speak is complicated or hindered by borderline reactivity! The therapist's negotiation for gaining permission to offer this feedback is critical for therapeutic progress with the individual with borderline personality disorder. Likewise his or her modeling of feedback is essential and foundational to the partner negotiating permission to give feedback at home. The partner being empowered to take a psuedo-therapeutic role with the individual may be the key to change. In a sense, the partner becomes the co-therapist for the individual and the couple. As the partner is more accepted, empowered, and becomes more skillful in giving appropriate feedback, the individual is able to increase his or her ability to reflect rather than just to react. Increased reflection facilitates progress toward integrating it into the consciousness and behavior of the individual. Increased modulation of affect leads to further reflection with increased ability to distinguish ancient context from current context. Greater ability will also make the individual more tolerant of and able to integrate partner feedback. This cycles back upon itself to incrementally, that is quantitatively increase reflection, integration, emotional regulation, and insight. The partner continues to provide a safe accepting haven and further clarification, confrontation, and interpretation.