19. Paranoid Challenges to Cple Rel. - RonaldMah

Ronald Mah, M.A., Ph.D.

Licensed Marriage & Family Therapist,

Consultant/Trainer/Author

Main menu:

19. Paranoid Challenges to Cple Rel.

Therapist Resources > Therapy Books > Conflict Control-Cple

Conflict, Control, and Out of Control in Couples and Couple Therapy

Chapter 19: PARANOID CHALLENGES TO COUPLE'S RELATIONSHIPS

by Ronald Mah

Elliot and the therapist are often perplexed by Clarissa's reactions to either innocuous or positive words. Communication includes verbal and non-verbal cues- both of which are subject to interpretation. Clarissa seemed to be pre-set to interpret with suspicion and negatively relatively benign feedback much to Elliot's frustration. "Individuals with cluster A personality disorders do not respond appropriately to affective cues and are unable to form connections on a basic emotional level (Ward 2004). As such, principles of interpersonal relations such as empathy and warmth are contraindicated in working with an individual with paranoid personality disorder" (Hayward, 2007, page 19). Elliot complained that, "Not only did Clarissa not get me, she often got me completely wrong!" He frequently had to explain and re-explain his emotional state and intentions without much success. Clarissa's aspersions against his relational integrity wore him down. In combination with her assumption of his disrespectful inner motivations, this adversely affected the relationship. The partners reported and the therapist could observe how their relationship had deteriorated by the quality of their communication. More and more verbalizations at home and in session reflected the erosion between them. "…for both wives and husbands, marital satisfaction was (a) negatively associated with the number of negative adjectives endorsed, (b) positively associated with the number of positive adjectives endorsed, and (c) negatively associated with the number of negative adjectives endorsed and subsequently recalled" (Whisman and Delinslky, 2002, page 622).

There is more activation of negative partner-schema that could be correlated with unhappiness with the relationship. Positive adjectives however are not similarly correlated with greater satisfaction with the relationship. This may be due to a bias in memory in favor for partner-relevant (negative) information partners who are less content. "It may be that negative information is more schematic for dissatisfied spouses, making it easier for them to retrieve negative information about their partners, which in turn, may maintain and possibly exacerbate their negative impressions of their partners. These findings support clinical observations that dissatisfied spouses are more likely to selectively attend to and remember negative partner behavior and information, and ignore or forget positive experiences with their partner (Whisman and Delinsky, 2002, page 624). The bias to recall negative information that dismisses positive experiences also affects immediate judgments attributed to the partner's intentions. Clarissa, for example might interpret Elliot's gift of flowers as coming from some guilt for some behavior he is hiding. Rather than enjoying his thoughtfulness, she suspects him to be manipulative. In addition, bias promotes and anticipates that otherwise positive or benign actions to be negatively motivated. She is likely to disparage his behavior whatever his motivations. Clarissa declared to the therapist that Elliot was not only going to use couple therapy to attack her, but also that he would try to take the house, the children, their savings, flaunt future girlfriends, and more in a litany of paranoid projection.

THERAPIST ISSUES

Trower and Chadwick propose that paranoia is not a response to real threat, but a cognitive tendency to misperceive negative evaluation from others. They argue that people develop distinctive ways of dealing with these ultimately feared sources of threat to the self by either agreeing (BM paranoia) or disagreeing (PM paranoia) with them" (Melo, et.al., 2006, page 272-73). This suggests two kinds of paranoia from either an insecure self or an alienated self. The insecure self paranoid personality are individuals with high need for reassurance and approval displayed in an anxious-insecure attachment cycle. Without a stable internal sense of self being cared for and missing a consistent loving caregiver, the individual stays anxious that he or she will soon be abandoned or rejected... again. Ambivalent or neglectful caregiver experiences could be the root of this. On the other hand, alienated paranoia is the individual's attempt to manage deep needs for acceptance and appreciation from others. The individual works furiously at avoiding being criticized, and thus relates to others through an avoidant attachment style. The adult outcome is to expect that intimate interactions will always be demanding and punitive. "Thus, these patients are said to experience intense apprehension about the possible failure to meet parental expectations, and therefore prefer to avoid relationships in order to prevent themselves being defined and constructed as bad by others (Blatt & Zurroff, 1992)" (Melo, et.al., 2006, page 273). The individual anticipates or misperceives the partner's and subsequently, the therapist's evaluation and armors him or herself.

The individual may be in denial about his or her feelings and actions in order to protect him or herself. The individual with paranoid personality disorder may well feel and present that he or she is fine and even managing his or her life relatively well. Their actions bother other people much more than it causes them any concern. Having concern for another person may create dependence, which would be difficult since trusting others is avoided. Entry into individual therapy or couple therapy or other attempts to get help only may happen if "projection and other paranoid defenses fail and they begin to feel depressed and anxious. But even then, they may go into therapy unwillingly and break it off prematurely. With a therapist, they tend to be at best irritable and guarded, at worst contemptuous, hostile, or even threatening" (Harvard Mental Health Letter, 2004, page 3). Therapy is often avoided until individual or relationship viability is on the verge of disintegration. It is often only when confronted with such an adverse consequence that someone with a characterological disorder (or substance or behavior abuse or dependency) will he or she start to consider trying to transcend or work against it.

In some cases, the characterological issues or addiction may be so compelling that the individual will not try to change, and suffer the negative consequences anyway. The therapist needs to be willing to skillfully use the leverage of imminent relationship failure, however tentative to increase the individual's willingness and skills to venture the challenge. That may mean feedback as blunt and incisive as saying, "Looks like you can be 'right" and lose the relationship, or you might consider looking at things- that is, Elliot differently and have a chance of staying together." This depends on clinical judgment that the therapist must make with the specific clients. The therapist should acknowledge how difficult the challenge is characterologically. "Clarissa, it's gotta be really hard to consider a different perspective, since it seems to make you wrong instead of holding onto being right." As the therapist takes and amplifies the consequences to promote change and growth, he or she joins the explicit or implicit request of the individual for change. "Clarissa, I know you want to be right about Elliot and what you do, but I also know you want help to make this relationship work. And that is going to mean doing some things differently." This may promote the relationship, but also stir up significant anxiety. The therapist needs to establish rapport while being aware that he or she is likely to become another target of paranoid projection because of anxiety. Trying to be perfectly receptive tends to be counter-indicated to honest therapy. It is not genuine and thus, will not work due to the hypersensitivity of the individual.

While attempting to avoid triggering paranoia, the therapist may find it more productive to directly address the potential and probability of becoming the target of project. "Clarissa, you may find my feedback and suggestions to be critical. You may experience what I do as attacking you. In fact, you almost certainly will be very sensitive to what you will consider to be taking Elliot's side against you." The therapist should model consideration of various options, question interpretations, and avoid assumptions. "What do you think about this?" "How about another way to interpret that?" "I need to check my assumption here." By checking assumptions and offering different and non-paranoid perspectives, the therapist engages the individual in alternative behavior patterns. The therapist needs to take care to not allow him or herself "to become either an aggressor or a victim. The therapist must build trust gradually, without trying to be too friendly, and avoid showing of anger or defensiveness. Complete honesty is essential because people with paranoid tendencies are highly sensitive to deception and holding back" (Harvard Mental Health Letter, 2004, page 3).

The therapist is charged to not allow paranoid beliefs go unchallenged yet finding ways to confront them productively. "That's interesting. I have another way to look at that. How would this work for you?" The therapist's "interpretations will be regarded mainly as accusations. Instead, the therapist must help patients acknowledge the feelings they have been defending themselves against." While some such as Clarissa vehemently presents interactions and history as undisputable facts, the reality as verbalized is Clarissa's inadequate communication about her deeper anxiety about being invalidated or hurt. The therapist should overtly address the deeper anxiety. "Seeing it that way must be very disturbing to you. That's gotta be kinda scary to experience it so negatively." Since others often fail to recognize the covert request for acknowledgment and nurturing, disappointment drives the reaction. As a result, "Clinicians… must be prepared for accusations, belittling comments, and litigious threats (Meissner 1996; Treatment Protocol Project 1997). As a rule, individuals with this disorder are ready to counterattack, provoking repeated confrontations (Carrasco & Lecic-Tosevski 2000), and their paranoia combined with aggressive behaviour warrants careful assessment" (Hayward, 2007, page 17).

The therapist must not allow him or herself to be intimidated by the potential anger of the paranoid individual. The individual's anger and accusations probably cannot be prevented, so the therapist will do better with accepting them as intrinsic to therapy since they are intrinsic to the personality disorder. The individual's paranoid reactions and criticism of the therapist can help the therapist better understand the existential reality of the individual. This will happen only if the therapist is aware and insightful of his or her counter-transference- that is, his or her personal emotional and psychological processes. "the client's continuous attacks provoke an intense anger in him, and this could make him interrupt the session. The therapist realizes that he has allowed himself to be stricken by this impulse to act in an anti-therapeutic manner. When therapists listen to a client they always place themselves in the latter's discourse, and the position they adopt depends on various factors: in particular, their personal history, theory, and training. With clients diagnosed with a PD, it is more likely, however, that a therapist's positioning depends on the activation of a cognitive interpersonal cycle (Safran & Muran, 2000), in which a therapist's actions and behaviours are provoked by a client's attitude and reinforce, in turn, the client's negative beliefs" (DiMaggio, 2006, page 73).

Rather than act out and confirm the paranoid expectations, the therapist who is self-aware and insightful may realize that he or she has also just experienced injustice. The individual's accusations of the therapist's clinical responses as insulting or unjustified have ignited the therapist sense of unfairness. The individual has made the therapist experience the same emotions the individual has been enduring. They "are both experiencing the same negative emotions and embodying the same I-position, which feels itself under attack from another seen as being malicious and sadistic" (DiMaggio, 2006, page 73). This can be used within the therapist to shape empathetic feedback- perhaps, to be shared with the individual. "I just realized how you must feel… because I just felt it myself. I was hurt and angry that you accused me unjustly that I…" The therapist then adds, "That must be what you feel when Elliot does…" The therapist then can validate the feelings without validating or addressing in the moment, the actual behaviors/history or the individual's interpretation. "That must really suck to feel Elliot doesn't care about your feelings… thinks you're manipulative… or hateful…"

Early identification of paranoid tendencies should help the therapist to anticipate the individual's hypersensitivity, hyper-vigilance, and habitual reaction. "Meissner (1996) notes that the individual's sense of autonomy is fragile and threatened, so much so that issues related to maintaining it permeate all aspects of engagement. Therefore, guidelines for engaging these individuals include clarifying issues before major problems develop (Treatment Protocol Project 1997), not being too friendly, warm, humorous, or inquisitive (The Quality Assurance Project 1990; Treatment Protocol Project 1997; Trimpey & Davidson 1998), and maintaining a formal, honest, open, and professional attitude at all times (Meissner 1996; Treatment Protocol Project 1997; Ward 2004). Allow the individual adequate opportunity to talk about their grievances or concerns (Treatment Protocol Project 1997; Ward 2004) but do not confirm or argue with their paranoid beliefs. Gentle reality testing may be useful if approached very carefully (Derksen 1995; Meissner 1996; The Quality Assurance Project 1990; Treatment Protocol Project 1997). The most useful approach is focusing on the 'here and now' (Treatment Protocol Project 1997)" (Hayward, 2007, page 17). These recommendations are appropriate but need to be adjusted over the course of therapy. Establishing initial rapport in a receptive atmosphere may need to be adapted to address the fundamental characterological issues that compromise mental health and relationships. The recommendations may be developmentally appropriate early in therapy to progress the relationship and the therapy to allow more intimate and provocative interventions. Withholding feelings and thoughts is dishonest, is sensed, and then often amplifies distrust. While the principles are theoretically clear, the therapist will find execution complicated. He or she must practice the art rather than merely the science of nurturing accepting confrontation within the session, over the development of therapy, and within the psychology of the clients.

COUPLE THERAPY WITH PARANOID PERSONALITY DISORDER

The greater difficulty of a generally receptive non-confronting strategy is that in addition to the therapist, the paranoid individual's partner hears him or herself being ripped as corrupt and evil. If the therapist accepts without confrontation the paranoid angry litany of accusations against the partner, the partner would experience the therapist as complicit in his or her unjustified crucifixion. If the therapist defers to the paranoid rants, it implies agreement and an alliance with the individual that corrupts rapport with the other partner. The partner such as Elliot watches the therapist carefully to see if the therapist can somehow manage someone like Clarissa and their dynamics differently. Unconditional positive regard is difficult to maintain, and may be unrealistic to attempt. "In general, paranoid individuals' diffidence and hostility can infect therapists, making them feel encroached on by patients questioning and testing. The permanent feature in such sessions is the feeling that one can, at any time, be misunderstood and will never manage to overcome the barrier of mistrust and suspiciousness erected by a patient for whom the world is an enemy to be feared. It is difficult to plan sessions beforehand; a patient's testing is continuous and intrusive, and even the most casual or involuntary gesture looks premeditated (McWilliams, 1994)" (Salvatore, et al., 2005, page 257). The therapist must be self-aware of any inclination to become aggravated and respond with hostility. Since he or she will be attacked including having his or her integrity impugned, the therapist must not counterattack. If the therapist does respond somehow in kind, the paranoid individual immediately gets confirmation of the therapist as another hostile person in his or her life.

Ironically, if the therapist gets defensive both partners may have negative reactions. "How interpersonal defensiveness might influence therapy outcome is not clear. Possibly, when therapists engage in defensive behaviors, couples form negative impressions or feel threatened, interfering with the development of trust or other aspects of the therapeutic relationship important to positive outcome, or therapy participants may respond to defensiveness by directing their resources toward defending themselves rather than to the therapeutic tasks at hand" (Waldron, et.al., 1997, page 241). Not only the paranoid individual but his or her partner as well may become defensive and criticize the therapist. Elliot, as the partner may have a long and significant history of seeing "the good side" of the individual and defending him or her to family and friends. If there were no "good side," the partner hypothetically would have ended the relationship long before. It has always been at least implicit that others criticisms of the paranoid individual to the partner, that the partner is either foolish to tolerate mistreatment or somehow deserving of a negative relationship. As a result, criticism of the paranoid individual or the relationship has been experienced as inherently criticism of the partner to the paranoid individual. Defending the paranoid individual becomes synonymous with defending the relationship and thus, of oneself. The therapist not only must be aware therefore of Clarissa being triggered by his or her verbal and non-verbal feedback and reactions, but how Elliot is activated by everything, including and especially criticism of Clarissa.

In couple therapy as it is in the relationship and in life, the underlying and overriding thrust and goal of the individual with paranoid personality disorder is to prove the righteousness of his or her perspective, and to prove the corrupt and evil intent and behavior of his or her partner. Any discussion about an incident or an interaction always goes to how the partner maliciously and purposefully violated the paranoid individual. To engage in such a discussion about what happened, when it happened, what one person did or the other person did, what precedents and history are involved, and whatever details that are supposedly relevant is essentially fruitless. The paranoid's goal is not to get clarity about what happened, to understand what the underlying motivation or intent may have been (it was obviously "evil" intent!), to achieve resolution or compromise, to improve communication, or to heal or to achieve greater intimacy. Further complicating therapy is there is often little or no insight as to how vicious his or her behavior is or has been nor how damaging it has been to the partner or to the relationship. The paranoid personality's egocentric perspective of the struggle in the couple makes the individual having empathy with the partner's perspective very difficult if not impossible to attain. The paranoid personality considers his or her perspective to be in mortal combat- competing to survive against the recognition or validation of the partner's perspective. It is as if only one perspective can exist and the other perspective will be annihilated. If this context is duplicated in therapy, positive outcomes are unlikely.

THROWN OFF THE MOUNTAINTOP

"To reinforce a therapeutic alliance, it is important to create a shared context during each session in which the overall emotional climate is positive and unlike the atmosphere of tension, anger and mutual reproach that characterise the PPD patient's narratives. If therapist and patient are emotionally attuned to each other and talk about shared interests, stereotyped dialogues are less likely to get activated, and it becomes easier for the patient to let the healthy parts of a self surface" (Salvatore, et al., 2005, page 257-58). In couple therapy, the therapist needs to find or establish some new and different shared context from the one that has corrupted the relationship to date. The partners' presentation in therapy is their search for a different context. From this the therapist needs to build a framework for growth and change. The therapist can use a metaphor, for example to do this. It starts with describing the dynamics of the battling couple. The therapist drew on a small white board a mountain with one person standing on the mountaintop.

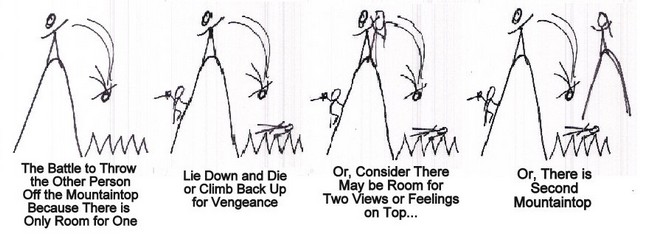

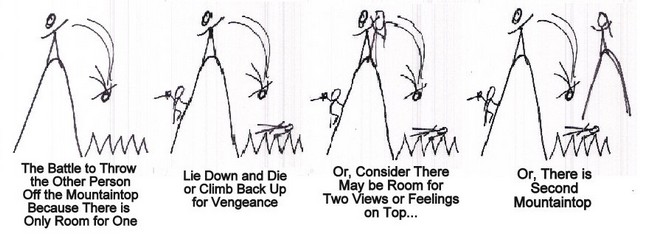

"Clarissa and Elliot, it seems like you get into it as if there's only room on the mountain top for one person's feelings, thoughts, or way of seeing things. As a result, any disagreement results in a battle to hold the mountaintop, resist being thrown off the mountaintop, and therefore throwing the other person off of the mountaintop." The therapist drew a figure dropping head first off of the mountaintop. "And then, whoever is thrown off of the mountaintop is crushed or impaled upon the jagged rocks below," drawing a jagged line underneath the mountaintop the figure falls towards. At this point, one or both partners may indicate with laughter, words, nods, or other non-verbal messages the relevance of this model on their relationship. One partner may smile and say, "That's me falling down." Or, "I'm not going to let you toss me... dear!" Humor at this point is a positive sign- an indication of being able to take perspective, be introspective, and taking responsibility. Playful accusations indicate the desire to continue play or the relationship despite prior injuries.

The therapist points out the harm in the process. "The problem with this is that for whoever still on top, your partner has been thrown down and is now injured. You've just hurt the person who is supposed to be your intimate life collaborator. What's more, if you are the one who has been thrown down and suffered pain, then you have a few choices: you can accept your place as an inferior perhaps abused member in the relationship, let intimacy hope "die," or you can climb back up for..." Drawing a person climbing up the side of the mountain with a sword in hand, "...vengeance! To get your partner back!" Partners in relationship with less severe pathology may laugh and joke about who is getting thrown off the mountaintop, but the point is taken as to the destructive nature of the dynamics. When the therapist asks, "Is this what you want? To be thrown down or to always have to throw your partner down? To have to fight to stay on top or to accept being thrown down? Either way, you both lose." The response may indicate Clarissa's sense of doom that there are no other options.

The therapist then draws another person on the mountaintop, "Perhaps, there is really space for two people on the mountaintop. There is space for two sets of feelings, or two sets of thoughts, or two perspectives that can co-exist without one destroying the other. Or..." drawing a second mountain with a person standing on the top, "that if necessary there is another mountaintop for the other person to stand. You agree to disagree and find a way to do it without annihilating the other person." The therapist should ask if this dynamic has occurred only in this relationship or if it had manifested in prior relationships. The paranoid individual may try to deny this pattern of relationship dysfunction and accuse that it is only the current partner that makes it happen in this relationship. However, it is almost a certainty that he or she has regaled his or her partner with tales of prior battles for emotional, psychological, or intellectual supremacy on other relationship mountaintops. The therapist should not find it difficult to get the partner to repeat the paranoid individual's stories of rivalry and abuse. Once the dynamic has been identified and owned, then the therapist offers a new context for functioning in a better way as a common shared goal.

Whether with metaphors or other interventions, the existential emotional world of each partner needs to be acknowledged. The therapeutic strategy or hope is to evoke the partner's empathy for the paranoid individual is vital to therapeutic growth. Unfortunately, strategy to evoke the paranoid individual's empathy for his or her partner is compromised or blocked by the paranoid condition. As the paranoid individual perceives only space for one set of feelings on the mountaintop, he or she is instinctively and compulsively competitive that his or her feelings be asserted. Since there is no space for another's feelings- not even a lesser space, the paranoid individual dismisses and/or attacks the partner's feelings. Clarissa attacks Elliot's feelings, thoughts, and perspectives. Only when the individual is secure that his or her feelings are securely sacrosanct in the relationship- not to be dismissed, can he or she begin to risk indulging in tentative empathy for the partner. The therapist must however judiciously validate and empathize with the partner's feelings and experiences while knowing that this threatens the paranoid individual. However, an unsophisticated clinical strategy to progress therapy or the relationship by evoking the paranoid individual's empathy for the distress of his or her partner will probably not be effective. He or she will experience this as criticism, while intuitively knowing that empathy for the partner undermines his or her victimhood-based self-righteous identity.

As a result, the initial primary therapeutic focus is developing security for paranoid individual that his or her experiential reality will be honored. The therapist should make a strategic decision to risk less attention on the partner's feelings. And focus initially on the paranoid individual to "validate the patient's emotions. Once the therapist realised that the main character... was fragile and felt criticised by others, he used the following intervention: 'I can understand your being distressed; living continuously with the feeling that you're not capable of anything and feeling that others constantly confirming this. It must be awful'" (Salvatore, et al., 2005, page 257). The therapist may be distracted from the individual's distressed experience because of the individual's aggressive style of defense. Conceptual clarity of the paranoid personality disorder and clinical awareness should lead to therapist feedback that will hopefully reduce the individual's tension. As a result, the individual may be able to acknowledge his or her experience.

As Clarissa has been described, her paranoia or sense of persecution sees herself as the object of blame and aggression by hostile others. She feels unjustifiably victimized and functions from a "poor me" versus "bad me" version of paranoia. "A somewhat alternative account of persecutory delusions has been recently proposed by Trower and Chadwick (1995), who have argued that there are two types of paranoia. According to these authors, people with 'poor-me' (PM) paranoia 'tend to blame others, to see others as bad, and to see themselves as victims' (Trower & Chadwick, 1995, p. 265), as they believe others are plotting to harm them without any justification. People with 'bad me/punishment' (BM) paranoia, on the other hand, are individuals who 'tend to blame themselves and see themselves as bad, and view others as justifiably punishing them' (Trower & Chadwick, 1995, p. 265). The therapeutic strategy should adjust to honoring a "bad me" paranoia if that were more relevant to another individual. "It must be hard to feel you're always the one who is wrong... who has messed up... who is messed up."

SELF-DISCLOSURE AS MODEL

A client with paranoid personality disorder may withhold important information from the therapist in anticipation of being judged by the therapist. Over the course of therapy, the therapist may note that the client says or does (or not say or do) things that indicate distrust of the therapist. If the therapist expresses disappointment or irritation at the client, this potentiallycreates a negative pattern duplicating old family- parent to child patterns. Overtly verbalizing the metacommunication may be productive. Rather than responded as expected by the paranoid individual, the therapist can venture some self-disclosure. The therapist can venture that his or her instinct was of irritation at still not being trusted after many sessions and interactions. Then, he or she can wonder out loud as to how it can be so. Using reflection upon the individual's history and current affect, the therapist can feed back that the individual was threatened and fearful in prior relationships and shows some anxiety in facial and body language anticipating the therapist judging or assaulting him or her. "Clarissa, you seem to see yourself as being pretty vulnerable and unable to really take care of yourself. As a result, your instinct is to protect and defend yourself by distrusting the intentions of others... including me. If you can talk about this thing- good. If you're not ready, then we'll get back to it when you are." "This kind of self-disclosure makes therapist's thought and feelings accessible to a client, reveals his inner world and makes it possible to create a sharing atmosphere, with both parties knowing that they are in a relationship in which they feel likely to be criticized or threatened" (DiMaggio, 2006, page 78). The therapist can continue to facilitate and encourage the individual revealing his or her feelings and anxieties, while blocking any shift towards blaming the partner. This is a fundamental challenge in working with the individual with paranoid personality disorder. Projection of blame to others in the outside world is core to the personality avoiding and thus, protecting self from self-examination and pain.

The therapist's self-disclosure is a model for the communication and strategy to take by the individual's partner when confronted with suspicion. The difficulty for the therapist to process hurt and insult from not being trusted, however is exponentially amplified for the intimate partner since the relationship is ostensibly based on mutual trust. The therapist validates the partner's experience with the paranoid individual through sharing his or her reactions and process. "How I felt and reacted emotionally to Clarissa is similar to how you Elliot feel and react emotionally. Is that correct?" The therapist can prompt then the partner's self-disclosure of his or her inner world of surprise, irritation, hurt, and anger as well. The challenge of this process is to do so in a manner that is not or minimally accusatory and judgmental of the hypersensitive and hypervigilant individual. The therapist should focus on the partner's feelings and block any potentially blaming comments. "Talk about what you feel and felt. Don't talk about Clarissa, what she said or did. We need to get your feelings out." The split between feelings and actions is intentional. "While we had similar feeling and reactions, what I did... how I acted including what I said, is different from what you did or said. Or, we should work on not changing your reaction... you can't change the instantaneous instinctive reaction, but maybe you change your response so that it works well for you... and is not so triggering, that is accusatory or judgmental for Clarissa." It is likely that the partner may have attempted such self-disclosure in the relationship, with the paranoid partner being inadvertently and unfortunately triggered. The task of the therapist is to interrupt paranoid reactions shifting the focus of discussion towards the partner with interpretations, clarifications, and reframing.

While the therapeutic process is conceptually sound and bear positive progression, improvement in the individual-therapist relationship may in itself intensify the paranoia. "Nicolo` and Nobile (2003) observe that persons diagnosed with PPD experience increased threat as they begin to feel closer to their therapists. These authors therefore suggest that therapists do not put pressure on them to participate in therapy. (DiMaggio, 2006, page 74-75). Greater intimacy and greater trust may be experienced as greater vulnerability to betrayal and injury. Since the individual may have experienced his or her deepest trust and thus, investment and hope that lead to his or her greatest vulnerability and greatest betrayal and devastation, paranoid instincts increase concurrent with client-therapist intimacy. The therapist can predict or reveal how increase of hope and intimacy can create greater anxiety to both Elliot and Clarissa for example. Elliot may have examples of this having already occurred in their relationships. Prior discussion helps both partners prepare for positive growth potentially or probably triggering regression. Specifically, the prediction to Clarissa that see might act out becomes a paradoxical intervention. If she resists the prediction and is able to not act out or act out less, that would constitute an improvement in their process. If she fulfills the prediction and acts out, then they both gain greater knowledge and sophistication about their process which they can use for further growth.

The thrust of couple therapy in this situation (similar to working with a couple with a borderline partner), includes the therapist clearly asserting that no member of the couple has the right or the permission to be abusive no matter how righteous or entitled they feel. This is a fundamental value and practice that runs directly against the paranoid personality disorder. The paranoid will not like this boundary, nor be readily able to follow it. Being vengeful or vindictive feels justified due to his or her embedded high arousal and accumulation of historical and anticipated resentments. In some couples, this boundary is more for the partner to hear and feel reinforced and validated. It would serve the partner and the therapy for the therapist to name the paranoid's dynamic of needing to prove the partner's corruption and to label it unacceptable for a healthy dynamic. For the individual with paranoid personality disorder, giving up his or her self-righteousness will be extremely difficult. Beyond being ego dystonic, justified aggressive vengeance has been his or her primary strategy of psychic survival. Therapy is challenged to assert these boundaries, while simultaneously identifying the paranoid dynamics and behaviors and their developmental etiology, and healing the deep wounds they come from.