1. The First C- Connection - RonaldMah

Ronald Mah, M.A., Ph.D.

Licensed Marriage & Family Therapist,

Consultant/Trainer/Author

Main menu:

1. The First C- Connection

Therapist Resources > Therapy Books > Therapy Interruptus

Therapy Interruptus and Clinical Practice,

Building Client Investment from First Contact through the First Session

Chapter 1: THE FIRST C- CONNECTION

by Ronald Mah

• Therapeutic alliance is made up of rapport or bond, goals, and tasks.• Therapists need to discover if expressed goals may have underlying objectives.• Telephone contact practices convey therapist availability.• First contact should go beyond information and data gathering.• Empathy is made up of cognitive empathy, affective empathy, and communication skills or communication empathy.• Implicit memory from child-caregiver relationships affects relationships because of emotional self-regulation problems.• Verbal Response Modes (VRM) vary in the degree of rapport building.• Selective silence builds rapport.• Non-verbal behaviors (particularly, certain facial expressions if genuine) affect rapport.• Appropriate self-disclosure, personal relationship, and humor build rapport.

The therapist needs to establish a strong connection with the client. The client may be an individual or some set of individuals such as a couple or a family. A therapeutic alliance between the therapist and client must be formed to meet the client objectives brought into therapy. The therapeutic alliance can be split into three components:

Rapport or bond - trust and emotional closeness between therapist and client

Goals - desired changes in client behaviorTasks - the process of therapy, i.e. strategies or methods of therapy to achieve goals

While the therapist may begin the initial conversation on the telephone or the first session by asking, "What are you here for?" the individual, couple, or family may not start with his or her goals. The client often starts with a description of the problem or issue. With a description, there is often an implicit presentation of the client-perceived goals of therapy. With couples, the communication may be "We fight too much." This may imply the goal of stopping or reducing the couple's fighting. "He doesn't talk to me," may imply the goal of improving the couple's communication. "I don't know if I want to be in this relationship anymore," may imply the goal of one or both members of the couple making a decision about continuing the relationship or separating. While each description implies a straightforward goal, the straightforward goal may have one or more deeper objectives.

"We fight too much," may have underlying issues and resultant needs or goals about respect, or power and control, or resolution of roles and boundaries."He doesn't talk to me," may about loss intimacy and attachment goals, or about gender differences or family-of-origin models that need to be examined and adapted."I don't know if I want to be in this relationship anymore," may to serve the goal of one partner to get the other re-connected in the relationship.

If the therapist accepts the perfunctory presentation of implicit or expressed goals, it may discourage the client's confidence with the therapist's sensitivity and skills. Setting goals or engaging in the process of therapy is made more difficult if the therapist and client are not securely connected beyond surface presentations. Setting goals may seem like the initial task of the therapy, without the therapeutic relationship it may seem disconcerting to the client. Sharpley et al (2006, page 344) says that, "prior to the setting of Goals or Tasks, the Bond between the counsellor and client must be firmly established. When the counsellor and client meet for the first time (i.e., during the intake interview), the building of the client-counsellor Bond must therefore assume priority. Failure to achieve this may result in dropout by the client." Gazzola et al (2003, page 82) discusses how "therapist techniques account for 1.9% of outcome variance while the therapeutic relationship is estimated to account for 30 to 40% of the variance." The first contact between the therapist and a potential client by telephone or even mail or e-mail contact may establish the direction of therapy. Bergantino (1997, page 385) says "To do family therapy one must get the entire family mobilized in the first telephone call or the first interaction" (page 385).

Some theorists or therapists consider the initial contact in a telephone conversation may help mobilize the therapist-client relationship, with resultant relevant ethical and clinical responsibilities and obligations activated. If the first contact or first communication goes well, immediate connection, rapport, and investment between the therapist and client can begin to develop. Prospective clients have been pleased and impressed that the therapist had returned their phone message within the same day. When a prospective client leaves a message that he or she would not be able to take a return call until the next day, the therapist can return the call immediately anyway. Returning calls immediately gives the message that the client message has been received and lets him or her know that attempts will be made to connect on the client's schedule or as soon as possible. The return call is an acknowledgement beyond professional practice and courtesy. It may be experienced as akin to the mirroring that a client has sought throughout life from important attachment figures. Upon finally connecting in person on by phone, the client often not only express appreciation for the quick return call, but also often complains about other therapists who never return calls. For individuals in private practice, the immediate return call may become a matter of sound business practices. Sometimes the client is "therapist shopping" from a list of referrals. Once there is contact and appointments scheduled by another therapist, such a client becomes a lost opportunity to the therapist who failed to call back in a timely manner.

FIRST CONTACT-AVAILABILITY

A prospective client wants to know that the therapist will be available to him or her. This is often extremely important as underlying attachment insecurities are already challenging the individual, couple, or family. After therapy commences, the therapist can tell the client that that the therapist expects him or her to be open and candid as much as possible. The therapist can assert a mutual requirement that neither the client nor the therapist compromise therapy by withholding concerns, but instead strive to stay available to each other. When the therapist tells the prospective client that he or she will not only be available, but also will continually check in with the client regarding any needs or the progress of therapy, the therapist goes beyond setting professional boundaries. The therapist is offering the secure attachment the client seeks. Insecure attachment in childhood with caregivers and perhaps, also with the therapist revolves around the uncertainty of the availability of the intimate figure. The client's experience of attachment does not wait for the first session. It begins with the availability of the therapist with the first contact. The therapist, if he or she has training at all in the first contact by phone may have been encouraged to keep it quick and focused on practical business aspects rather than any clinical work. Ironically, this approach may mean the therapist is to avoid facilitating availability and attachment. The first contact or phone intake is restricted to names, phone numbers, fees, managed care information if applicable, and scheduling, with the barest discussion of clinical information: individual or couples or family therapy, and possibly the presenting issue. Gathering information, while intrinsic to the work needs however to be timely. "…for beginning interviews, the bond aspect of the therapeutic alliance must be seen as of paramount importance. The lack of this bond may account for the fact that half of all clients drop out of treatment or terminate counselling by the fourth visit… Further, in an analysis of the reasons why clients dropout… noted that the major associated factor appeared to be the counsellor's focus upon data-gathering rather than building rapport" (Sharpley et al, 2000, page 101).

In certain situations, only data gathering can occur during the initial contact. For example, agencies or offices with receptionists, the client has no contact with a therapist until the first session. Sometimes the client call or the responsibility to make the return call is transferred to an intake therapist who may gather more clinical information. The intake person often will not be the client's therapist. Once a therapist has been assigned to a client, he or she then contact the client to schedule appointments. The higher incidence of no shows and cancelations of initial appointments in agency or non-profit human services counseling centers may be partly a function of this disjointed human process, in addition to issues intrinsic to the demographics of who is served by such organizations. The private practice therapist combines all this into the first person to person conversation. In all cases, the therapist may have been admonished by office policy, graduate school training, or professional development trainers not to begin or conduct therapy in the initial phone conversation. This type of business practice runs the risk of the therapist not making any connection with the client who may be uncertain of his or her needs, be marginally invested in therapy, and/or seeking "something" about a therapist among many therapists. It is problematic to assume that the client who makes the initial contacts is committed to therapy and will follow through on a scheduled appointment. Many clients will follow through, but someone may not because the initial phone conversation may as well have been an automated phone answering system- a robotic experience. Human to human connection occurs when the therapist interacts as a human being.

The telephone conversation as first contact serves more than just to coordinate availability to schedule the first session. The first session is more likely to occur and be productive if the therapist has the goal and strategies for the first telephone conversation to make connection with the client. Fortunately, there has been significant attention given to verbal communication and building rapport. "When building rapport, several strategies have been established over the past decades. Nonverbal… and verbal… responses of particular format and type have been associated with instigation and strengthening of rapport. Perhaps most commonly referred to (and taught in counsellor training programmes) is verbal behaviour" (Sharpley et al, 2000, page 101). A productive phone conversation between the therapist and prospective client builds rapport and begins to transform the person into a committed client, and scheduled and attended appointments become the natural consequence. At the same time, the caution that the conversation should not become therapy is well intended because of the limitations of this type of interaction. There is no history, no commitment to the process, no visual or olfactory cues; and the therapist cannot do more thorough mental status exams. Yet most theories of the psychotherapy process begin with establishing rapport with the client. Many find that the rapport between the therapist and client as the key predictor of effective therapy. The therapist can establish or begin to establish rapport with the first phone conversation, which may mean "doing therapy" or not depending on their theoretical orientation. Where the phone call is between the client and an intake person of an agency or organization who sets an appointment, the first contact between the therapist and the client will be the initial session. The principles discussed here are applicable for the face-to-face meeting as well as for the phone conversation (and as already mentioned, for marketing). The initial connection or rapport can include therapists offering of themselves for clients to experience and hopefully, to connect to. While many programs train the therapist to keep the initial phone contact very short and/or to spend most of an initial session listening rather than speaking, this may be counter-therapeutic. Short conversations and limited therapist expression may prevent clients from developing the rapport they are seeking and need. In fact, the balance between therapist verbal activity versus listening throughout therapy affects rapport. "…counsellors who speak with their clients do not run the risk of reducing rapport, and may engage in what was termed verbosity… The suggestion that effective counsellors should be simply 'good listeners' is clearly without empirical basis here, and is better reframed as counsellors who listen and respond effectively, using silence in conjunction with verbal responses… Those counsellor minutes which showed greater amounts of counsellor verbosity were significantly associated with higher ratings of rapport than counsellor minutes which showed lesser amounts of verbosity" (Sharpley, 2000, page 112)

What a therapist does or does not do, both affect the client's experience of the therapist and the process. Clients who are tentative, marginally invested, or hopeful but not confident and committed may want to know what they are "getting into." To put it another way, they want to begin to know "who" they are getting into "it" with. What can the therapist present in the initial contact to foster connection with the client? Lawson (1994, page 245) noted in a study that there were relevant changes in presenting problems that occurred between the time an appointment was made and the first session. The therapist may express expectations for change are important to client change. When the therapist responds to information presented by the client by identifying behaviors as solution behaviors, it changes the client's expectancy about a solution. For example, the therapist can confirm that seeking therapy is a good move or a positive sign of trying some change versus staying the same. Lawson says the therapist "can significantly influence a client's expectation about a preexisting solution to a problem by communicating a definite expectancy" (page 247). The therapist interactions and questions in the initial telephone conversation do not only draw information, but also convey the therapist's expectations that there will be change. The client's experience of the therapist and of the therapist's expectations can affect the client immediately. The therapist expectation of change can lead to the client's expectation of change. This experience is a change in of itself. Any change before the first session becomes foundational to the therapeutic process.

The therapist can create early therapeutic change in a multitude of approaches. For example, circular questioning according to Scheel & Conoley, 1998, page 222) was developed by the Milan team to connect individual understanding into circular views about a situation within a family or a couple. In circular questioning, the therapist asks questions about differences within the couple to discover and reveal systemic processes. Differences in beliefs among partners are explored and lead to hypotheses of the couple's dynamics. The therapist develops hypotheses, which are further explored. Sharpley et al (2002) found that open questions led to more discussion of client feelings than did reflections of feelings or restatements. Some theorists found that interpretation was most effective. Others found self-disclosure was most effective in engaging the client, with direct guidance the least effective. Open questions were able to produce insight and cognitive restructuring in clients. Combining open questions and paraphrases decreased client anxiety, while combining paraphrases and less therapist approval increased client self-esteem (page 101). During an initial phone conversation, these types of inquiry common in the therapy room may be utilized to not just begin assessment and diagnosis, but through sound assessment and diagnosis establish connection with the client. The hypothesis and pointed question presented to a caller who may be one member of the couple may be as simple as "It sounds like you've been wanting therapy for a long time, but your partner has been resistant. Is that dynamic unusual between you?" What does this type of interaction do for a tentative or potential client?

RAPPORT-EMPATHY

The prospective client wants to find out if the therapist is for and with him or her. The therapist may connect using various approaches depending on his or her theoretical orientation. Key to developing a strong therapist-client rapport is the therapist's focus on the person of the client rather than on theoretical or therapeutic interventions. "The quality of doctor-patient communication remains central to the effectiveness of… consultation, both in terms of immediate patient satisfaction and longer-term health outcomes. In this context, analysis of effective communication in the consultation has increasingly been focused on the patient-centredness of the encounter, where the patient's perspective is specifically addressed alongside the presented symptoms. The central goal here is a professional rapport between doctor and patient, a therapeutic alliance based on trust and co-operation and established through a shared understanding of the patient's perspective" (Norfolk et al, 2007, page 690). Empathy refers to the imaginative cognitive skill of one person that accurately perceives and understands the other person's inner feelings and/or thoughts. Empathy involves both emotional and cognitive parts, that is the perception or relating is both to feelings and thoughts. In addition, the other person also conveys empathy in some behavior that is recognized by the first person. Norfolk argues, "that the verbal and nonverbal skills involved in relationship-building are interpersonal communication skills rather than empathic skills" (page 691).

Communication skills are so significant that Ridgway & Sharpley (1990) add communicative empathy to cognitive empathy and affective empathy to name three instead of two major types of empathy. As the therapist picks up various cues and signals from the client, empathy occurs within him or her. The therapist then interprets the meaning of the cues and signals for the client. The therapist proceeds with in interpersonal therapeutic interactions with the client. He or she makes observations, interpretations, or interventions, which convey empathy, that is convey his or her understanding of the client, couple, or family's emotional and/or cognitive processes. Ivey & Matthews (1984, page 237) says that therapy is about helping the client develop a new cognitive balance or equilibrium. In the early stages of humanistic oriented therapy, therapists are accommodative as they attempt to mirror the client's picture of reality. In contrast, psychoanalytic and behavioral therapies emphasize providing a new perspective of the world for the client. Therapy, however must also match the cognitive history of the client. Successful therapy occurs when the therapist "both accommodate and assimilate to client reality." Qualitative interpersonal communication demonstrates the therapist's empathic connection with the client or couple. Initial and subsequent therapist communication and actions validate the client or couple's experiences or cognitive history. Connection and rapport is enhanced.

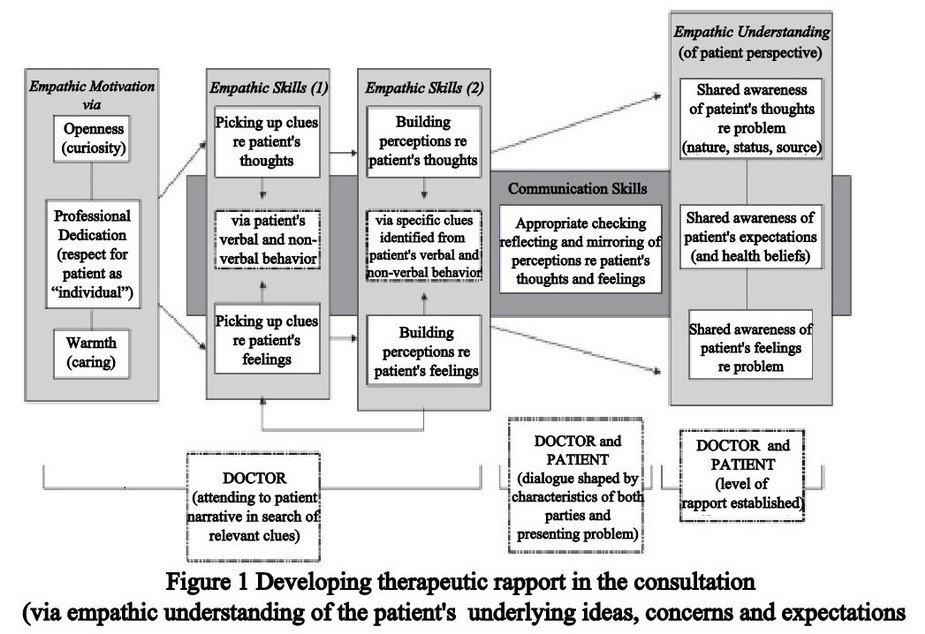

Norfolk et al (page 692) use the following chart to describe how the therapist comes to an empathic understanding of the client.

Norfolk says empathic understanding or connection with the client starts with the therapist's empathic motivation. A key to the process comes from the therapist who has innate interest or curiosity, which involves being open to new possibilities and innate warmth or caring for others. This involves both an intellectual curiosity, which is linked to cognitive empathy and warmth towards people. This in turn is linked to affective empathy. Susan M. Shimmerlik, Ph.D., in her article "The Implicit Domain in Couples and Couple Therapy," demonstrates how her intellectual curiosity and knowledge combines with cognitive empathy and warmth combine in her treatment of a couple. She begins with a review of literature from neuroscience and research on the "infant/caregiver relationship that conceptualizes and documents development as a recursive process in which neuro-biological, relational and intrapsychic processes mutually influence one another" (page 373). The internal experience is seen as emerging from and inextricably tied to relational experience of the infant and caregiver. The infant and caregiver mutually regulate each other states bidirectionally, through perceptual systems and affective displays. These lead to identifiable patterns of interaction. Communications occurs nonverbally: tone of voice, vocal rhythms, bodily movements, gestures and particularly facial expressions that regulate the infant's states of arousal. From the quality of these communications comes the development of the infant's ability to self-regulation (page 373). Each infant, later child and then adult develops two memory systems: the explicit and the implicit.

"Explicit memory, or declarative memory, is the memory of conscious awareness of factual knowledge and autobiographical events and includes narrative memory. Implicit memory, on the other hand, is an earlier form of memory that does not require conscious processing. It is memory that involves the direct encoding of experience into somatic, perceptual, emotional and behavioral representations; remains outside of our awareness; and is thought not to involve an internal sense of recalling." One form of implicit memory is procedural memory, which has to do with patterns of action responses such as riding a bike. What is critical for the present discussion is that it is now believed that beginning in early infancy, relational and affective information is communicated, processed and stored through the implicit or procedural system… 'implicit relational knowledge’ …during the vital exchange of signals between infant and adult, underlying patterns and regularities in the attachment relationship are detected, extracted, encoded and stored. Thus, the growing infant acquires implicit relational knowledge regarding what relationships are like and how they are conducted in ways that were never conscious. There is now increasing evidence that throughout life we continue to process, store and communicate relational, affective information out of our awareness through the implicit system, or as the enactive domain" (page 373-74). The experiences within this first relationship become the template on which subsequent intimate relationships are experienced. Shimmerlik then discusses a couple, Bob and Debbie, who she recognizes as replicating the dynamics that she had academically presented. Each partner has child and caregiver experiences that created difficulties in their ability to self-regulate emotionally. Each partner is looking to the other for help regulating emotions and each is miserably failed. The implicit memories from both are being played out in the couple’s relationship to the frustration of both partners. Underlying patterns of attachment hurt, loss, and trauma are drawn from each other in an unrelenting dysfunctional dance.

Fortunately, as Shimmerlik is both intellectually aware and emotionally attuned to their frustration and pain, she is able to identify their process. "…what the three of us came to understand over time was that what I witnessed was a highly patterned, mutually constructed, interactive affective sequence, carried out through the implicit or enactive domain, in which Debbie is highly attuned to Bob's pain and Bob in some ways counts on her to divert him, enabling him not to experience his pain and allowing her to experience her own pain via him. He complains of her intense reactivity but feels safer having her express feelings to which he has limited access and which make him feel out of control. On the other hand, although she complains about his distance and unresponsiveness, she becomes extremely anxious when he exposes his vulnerability in any way. Sensing him in pain triggers for her experiences of responding to and taking care of her depressed, disabled mother and younger brother after her father walked out, leaving her no opportunity to express her own needs. This process between them serves affect regulating functions. Over time, Debbie and Bob have become exquisitely attuned to what they themselves and the other can tolerate. When Bob feels anxious or vulnerable he knows on some level what he can do to trigger her reactivity, helping him to disown his vulnerability and allowing her to express her pain in a way that feels to her as if it is about him. This formulation of a mutually constructed, recursive process represents a central feature of a family systems approach. What family therapists have always paid attention to is looking at behavior in the context of relationship patterns, and specifically the repetitive sequence of behaviors between people in interactions and how these take on self-reinforcing properties" (page 374-75).

Shimmerlik is able to relate to each of their attachment styles from their behavior and their history, and how and why they react virtually simultaneously to each other implicitly (page 376-79). These implicit interchanges occur out of awareness and patterned within relationships. They create powerful, embedded interpersonal contexts that are not accessible outside the context of the relationship. They are acted out in the relationship. Only then and there can they be accessed. Since they are unconscious, they cannot be reported for example, to the partner. It becomes an understatement, when she states "The understanding of implicit processes in couples work becomes even more complex when we consider the triad of the therapist and the couple" (page 380). Working through the complexity is the core of couple therapy challenges. Shimmerlik demonstrated how her theoretical and emotional empathy connected her to the couple when she becomes aware of a sudden shift within not just one partner, then the other, but also within herself. Empathy connected her so that what happened in them caused something to happen within her. She stopped and asked, "What just happened?" She had picked up how she had gotten triangulated into their system. Therapy moved to untangle what happened and what it meant about her as the therapist and then about them as a couple (page 382). She goes on to describe how understanding herself, including being in tune to her own feelings allowed her the empathic connection with the couple. "It was only when I was able to go beyond the dyad, to consider the possibility of my own need to make this about her and me, thereby colluding with both of them to protect Bob in his vulnerability, that we were able to get beyond the impasse. It was at this point that I was able to consider his participation in this complex, triadic enactment. I began to notice that even in moments when I was successful in slowing her down and helping her to make room for him, he would respond in such a way as to reengage her and deflect my attention back to her. This is an example of how dyadic interactions cannot be fully understood without understanding the ways in which they are embedded in larger interpersonal configurations. As we were increasingly able to define this as a collusion between them, in which I had participated, it became more possible to look at how this pattern of interaction protected each of them" (page 382). Shimmerlik gave feedback, "'I am not sure where this is coming from, but as I listen to both of you and how angry you are, I am aware of feeling sad. I know how important this aunt was to both of you. I am wondering how it is that I am feeling sad and neither of you seems to be experiencing the sadness.' As we talked more about this, they were both slowly able to contact their own sadness" (page 383).

Shimmerlik makes a distinction between understanding the couple based on their reports of experiences and history versus what gets played out in therapy (page 384). The therapist can help the couple make sense of this by pointing out that one partner is correctly getting or giving an affective relational communication that the other person is not aware of or fully aware of. She points out that "the potential subjective meaning of that communication is extremely complex." When such a communication and ensuing interaction happens in therapy, the therapist can interrupt the dynamic and focus everyone on it, perhaps by asking, "What just happened?" This helps everyone understand that something happens that is not completely understood but is very powerful with real consequences in the relationship (page 385). In Shimmerlik's description of her process with this couple, she brings together her theoretical and intellectual sophistication and her emotional sensitivity. While her cognitive empathy has clearly been enhanced through education and research, her affective empathy may be from inherent personal qualities. Cognitive and affective empathy undoubtedly contribute to and stimulate development of her considerable therapeutic skills. Of concern is whether the therapist role draws out empathic qualities from a so empathetically endowed individual, or if an aspiring therapist can acquire such qualities through training, experience, and practice.

VERBAL RESPONSE MODES

There is a positive relationship between therapist exploration and warmth/friendliness with competence doing interpersonal therapy. However, Svartberg (1999, page 1314) found that therapist competence decreased when doing interpersonal psychotherapy with more difficult patients. Therapists who used prescribed techniques skillfully with especially challenging clients did not have greater success in therapy, but were perceived as less competent. This seems to imply that clinical skills or techniques are not in of themselves sufficient for effective therapy, and that therapist-client rapport may be significantly more important. If the therapist does not have strong innate affective qualities, then Norfolk recommends he or she can try dedicating him or herself professionally to understand the client to gain the empathic motivation for the inquiry (see the first box - "Empathic Motivation via" on the left of the previous chart). Norfolk also noted the notion of attending, either explicitly or implicitly encouraging the client to share his or her story. Evoking the story demonstrates therapist concentration on and interest shown in the client. Effective attention to the client may be more specific to affective empathy as opposed to the learning the details of the client history.

Hickling et al (1984, page 236) found that note taking can distract the therapist and keep him or her from attending to the client. Note taking is intended to help the therapist keep track of relevant information revealed by the client. Their research found that sessions where the therapist took notes were rated less effective in therapist effectiveness, client reaction, and total therapeutic impact. This may be because the client does not experience therapist attention to the factual content of client words as genuine interest in the person and internal affective world of the client. In addition, a positive attitude or interest may not be sufficient if the therapist does not have sufficient diagnostic skills. Empathic motivation by itself does not guarantee that the therapist will skillfully pick up clues about the client's thoughts and feelings from attending to both verbal and non-verbal behavior and communication (second box labeled Empathic Skills (1)). The therapist also needs conceptual skills to develop accurate perceptions (meanings, theories, connections, and so forth) about both the client's thoughts and the client's feelings (third box labeled Empathic Skills (2)). The therapist can draw upon intuition and training, experience, education from other experiences with similar clients (e.g. related to age, gender or other demographics) or patterns of clinical presentations (page 694), and through consultation with experienced mentors. As the empathic process occurs within the therapist, the client still may not be aware of how and how accurately the therapist has connected to his or her thoughts and feelings. The therapist needs to possess strong communication skills (as indicated by the gray connecting box in Norfolk's graphic) to articulate or demonstrate both empathic interest and empathic skills. Unless the therapist can convey his or her sense of connection, the client does not know whether the therapist wants to listen or understand or has listened and understood the client.

"Communication skills perform two specific roles in helping establish a therapeutic relationship in the consultation. Firstly, they act as eliciting skills, encouraging patient disclosure. This involves both verbal skills (e.g. appropriate use of open questions, reflecting or echoing patient words, clarifying and summarising) and non-verbal skills (e.g. warmth of voice, appropriate use of silence, smiling, nodding, mirroring of posture). Secondly, these skills will determine the doctor's empathic accuracy through testing or checking how well he has read the patient's verbal and non-verbal behaviour in terms of the clues it offers to the patient's thoughts and feelings" (page 692-3). Sharpley et al, (2000, page 101-02) noted that using paraphrases, reflections of feelings and minimal encouragers helped build initial rapport. Open questions may also do this, while closed questions tend to focus on specific behavioral aspects and forming goals that may be more appropriate towards the end of the initial contact (page 101-02). Therapists who intuitively, by personality, or by training interact with clients in identifiable typical patterns form rapport more readily and deeply with clients. "The three vrms (verbal response modes) which were significantly associated with higher STC (the standardized client) -ratings of rapport (i.e. minimal encouragers, reflections of feelings, restatements) are traditionally seen as the cornerstones of effective counselling, and should continue to remain so. Minimal encouragers help clients to move forward and explore their material without undue counsellor interruptions. Reflections of feelings focus upon the most common aspect of counselling (i.e. why clients seek counselling rather than simply a chat with a colleague or friend) and, as such, again underlie the value of a listener who responded to much more than simply factual or cognitive matters… Similarly, focusing upon the client's material via restatements rather than attacking faulty schemas or cognitive patterns (as in hard-line cognitive therapy of previous decades) also is significantly associated with rapport building. Questions, information-giving and interruptions although not showing statistically significant differences between high versus low rapport minutes, were also clearly used more in the former than in the latter" (page 113).

At the beginning of the initial contact or the first session, the effective therapist might respond to client's concerns factually through restatements and emotionally by reflecting feelings. The effective therapist should show focus on the client and his or her concerns through restatements, focus on client's emotions through reflecting feelings, and use minimal encouragers after each important pertinent comment by the client. Ridgeway & Sharpley (1990) says a therapist statement would be experienced as expressing empathy or identification with the client if it met any of the following criteria:

repeating same or virtually same words;paraphrasing words of other, whether same topic, subject, or person;words of agreement (e.g. 'Right' 'That's right'!'Yes'! 'Uh huh'! 'That's it');completion of other's sense, even if interrupting;inferred sense from other's words;description of other's state, e.g. 'As I look at you now I can see you are tense and anxious about this'

The first three criteria may be purposefully met with relative ease, as the therapist's theoretical orientation requires it. Repeating what the client has said either essentially as a therapeutic parrot or rephrasing the same without adding any substance, perspective, or nuance does not require tremendous therapeutic awareness or insight. Nor, does merely agreeing with an emphatic "Yes!" to whatever the client has presented seem clinically challenging for the therapist. However, the last three criteria recommended require greater therapist empathy and/or insight. Through instinctive interaction or personality, and/or through extensive training and experience in developing attuned response modes, the therapist can convey his or her level of accurate understanding of the client's thoughts or feelings. Therapist insight is required to complete the client's thoughts or to infer client's semi-conscious intentions from incomplete and inarticulate expression. Affective empathy and emotional communication skills are required to identify and then, describe the client's emotional state. And then, the therapist must do it again… and again. Rapport or empathic understanding is related to such therapist's specific skills applied consistently over the entire course of therapy. A specific challenge in couple or family therapy, is to convey empathy with each member of the couple or family effectively amidst their conflicts.

Consistent communication skills as with all therapist skills develop over time and with experience. Sharpley et al (1997) found that fifth year trainees used more verbal responses than fourth year trainees and had higher levels of client-perceived rapport. With additional training and experience, the therapist gains more "confidence and expertise in making verbal responses as rapport inducers, rather than occupying a more passive 'sit and listen' style, thus leading them to be more verbose than their less-trained colleagues. It also appears that being an active counsellor by contributing to the two-way verbal interchange adds to the degree of rapport experienced." Rapport with a client is not an instantaneous occurrence or is sustained through singular experience, but develops over time and experience in the therapy. Norfolk et al (2007, page 693) says, "It is important to recognise that the rapport established between doctor and patient is not a static moment or outcome, but rather a dynamic, iterative process in which the doctor attempts to reach an increasingly accurate understanding of the patient's thoughts, feelings and expectations. The strength of the rapport can therefore fluctuate, and the pace at which it develops will often vary between patients." Ivey & Matthews (1984, page 239) concur saying, "It must be remembered, however, that rapport is not an event, but rather an interactional process that extends throughout the counselors contact with a client." They further remind the therapist that therapy should not progress if any unintended nonverbal or verbal discrepancies between the therapist and client had not been proactively addressed. A client or particularly, a partner can be confused, upset, or angered in the therapy (especially, in couple or family therapy when there are multiple relationships to be managed) because of his or her partner's or other family member's words or behavior or the therapist's actions or inactions. Therapist attunement to these client experiences comes from empathic connection and rapport that are critical in all stages of therapy. Early in the process with the first contact and the first session, the client has hope for therapist empathy for him or her without yet having the experience of it. If the therapist fulfills the initial hope for empathy, early and ongoing experiences build rapport and confidence that the therapist will continue to be empathically connected to the client- in couple therapy, with each partner. The pace at which rapport develops depends on how skillfully empathic motivation combined with empathic skills and conceptualization is further expressed in skillful therapist communication to create empathic understanding.

SILENCE

Along with research on verbal response modes and therapist verbosity, silence has been found to be an important aspect of communication, especially of therapeutic communication. Silence as valuable in communication may seem contradictory, but verbal expression is often only a small component of overall communication. It is not more or less words or silence per se that determine effective communication, but how they and other methods, strategies, or techniques affect communication. Sharpley (1997) makes an unequivocal assertion about silence in the therapeutic process. "All data collected and analyzed here point to one conclusion -- that silence is associated with increased client-perceived rapport. This finding confirms… and extends… by examining the effect of silence from the client's viewpoint rather than counsellor's evaluations… While there are sometimes differences between clients' and counsellors' ratings of the counselling process… it appears… two sources of evaluation agree that silence occurs more frequently during very effective interviews than during less effective interviews (whether rated once after the interview is completed or minute by minute during the actual interview process itself)."

In subsequent research, Sharpley et al (2005) looked at silence and rapport in initial interviews. Silence that was terminated by clients was more likely to occur in successful cases, while unsuccessful cases had low frequency of silence. On the other hand, a study of the effects of silence in telephone therapy interviews reported that higher occurrence of silence was followed by a lesser probability of the client later seeking in person therapy (page 150). On the telephone, communication is limited to verbal delivery and messages along with tone while in person interactions include an additional multitude of visual cues (facial expressions, body posture, use of hands, etc.) and environmental cues. On the telephone, overall communication is dependent on verbal communication and silence may not be as desirable. Without various visual cues, silence may imply a lack of interest or connection. In person however, "Silence should be seen as part of the interaction, rather than the absence of the interaction. During silence, clients have time to reflect, think about what they are feeling, and to simply feel their emotions. Counsellors must allow this reflective time to flow as a vital part of the therapy process" (page 158). Silence in therapy, including the first session may be useful with the building of rapport, particularly as it may convey the therapist being interested in the client reflecting upon their emotions and actions.

Therapist silence in the initial phone call or early in the first session may be uncomfortable to clients and is not recommended. A silence, which was begun by either the client or therapist and then ended by the client was likely to help build rapport. The client has a positive reaction to when the therapist asks an open question and allows the client to reflect upon it and then terminate the silence with self-disclosure. A silence initiated by client self-disclosure or agreement and then terminated by client self-disclosure was also rated high in rapport. Silence appeared to be a thinking period, a time for reflection, and a time from which additional self-awareness emerged from the self-disclosure. The therapist who is uncomfortable with silence may often interrupt the opportunity for the client to pause and explore his or her thoughts and feelings. When the client perceives that the therapist understands and respects the client's process, it enhances their rapport (page 158). A therapist uncomfortable with silence may inadvertently communicate impatience or irritation to the client. There would appear to be an implicit demand for a quick response, rather than meaningful expression from a thoughtful and heartful exploration. The client may try to please the therapist and rush or cut off his or her contemplative process, only to become resentful later.

NON-VERBAL CUES

Eye contact, facial expressions, and body posture are among other non-verbal processes that provide important information between people beyond or in addition to verbal communication. People look for social and emotional cues, including for positive or negative cues in other people's eyes and faces. Eye contact varies in propriety and meaning depending on cultural experiences and family-of-origin experiences. Direct eye contact has a range of meanings from being considered intrusive, aggressive, or impolite to being considered inviting, including romantically for flirting or convey respect and attention. In therapy, since eye contact can be indicative of a variety of issues as well, the therapist should consider his or her own comfort and pattern of eye contact. Sharpley et al (1995) found that eye contact enhances building of rapport between therapist and client. It intensifies the emotional experiences of the client in the 'work' stage of the session; and assists the client in decision-making for lasting behavior change. They found that high rapport between the therapist and client varied in the amount of eye contact during different periods of the session. In the first part of therapy, when the client is most likely to be presenting sensitive experiences and information, lower eye contact was appreciated. Higher eye contact may have been considered more confrontational or perhaps, judgmental given the content of client disclosures. In the early part of the first session, the client is more likely to be anxious about the therapist's reaction to his or her issues. In the middle part of the session, high use of eye contact was associated with high rapport when the client confronted issues and feelings through interactions with an intensely involved, present, and real therapist. There is also high eye contact with high rapport during the next-to-final part of the session when the client may be moving to decisions about behavior changes. The client may require active interaction with the therapist, including needing options, confirmation, and especially support to make challenging decisions.

Among other non-verbal and verbal behaviors that affect rapport, therapist facial expression may be the most influential with the client. Sharpley et al (2006, page 349-51) examined the effects of therapists' facial expressions:

Interest-excitement,Hypothesized interest,Enjoyment-joy,Surprise-astonishment

These were considered for the degree of rapport experienced by a client. They found there was significantly more time with therapist facial expressions of Interest-excitement and Enjoyment-joy during periods experienced as high in rapport as those rated as low in rapport. There was also significantly less of therapist facial expression of Hypothesized Interest in high rapport minutes. Interest-excitement is interest that is exciting. The individual feels engaged, caught-up, fascinated and curious, and wants to investigate, become involved in or expand upon the self. The individual (the therapist in this situation) tries to incorporate new information from the person that excited the interest. In the beginning of the initial interview, frequent facial expressions characterized as Interest-excitement by the therapist correlated with high rapport. This would be when the client was probably presenting initial concerns and then exploring his or her emotional reactions. The therapist if so interested and excited appears captivated and alert, looking and listening or attending intensely. The client would likely find such a therapist as empathetic and rapport would increase (page 353). During the middle and later parts of the session, client felt high rapport as the therapist increased their Interest-excitement facial expressions when the client's work tended towards some resolution and planning for later behavior. Periods of the session that were rated low in rapport had decreasing therapist Interest-excitement facial expressions compared to the beginning of the session. This change in Interest-excitement expression frequency may be because the therapist is less engaged with the client. "Clients who do not feel that their counsellor is interested in them or their concerns will be less likely to rate the rapport they are experiencing as positively as will clients who receive facial expression reinforcement from their counsellors and thereby continue to explore their concerns and plan for their remediation" (page 351). The client experiences and appreciates warmth conveyed by therapist's Enjoyment-joy facial expressions. The client may appreciate any therapist enjoyment or approval of positive energy when the client shows strength, determination, realization, behavior change, or other significant therapeutic or life gain (page 353-54).

On the other hand, although the person or therapist who shows Hypothesized Interest may appear interested, there are no discernible facial expression changes that to confirm the interest. Thus, the interest is a hypothetical state of interest rather than something the client can see in the therapist's facial expression. Therapists who were rated low in rapport showed Hypothesized interest particularly in the last part of the initial session involving more behavior planning. This may be reflective of lower therapist engagement. In other words, therapist interest may not be genuine (page 351-52). "In fact, this facial expression is almost blank. Although this is suppositional at this stage, this particular facial expression might be that which is associated with the commonly-stated 'distant and clinical' facial expression and actual lack of emotional involvement that is sometimes attributed to mental health workers by the popular press. If this were the case, then the implications for purely cognitive or analytical therapy approaches that do not emphasize the emotional linkage between counselor and client are relatively poor in terms of development of rapport... The clear and unequivocal expression of interest, excitement and enjoyment appear to be positively linked with client experiences of rapport, but expression of non-involvement and 'clinical' interest is not" (page 354). Sharpley et al, (2001, page 268-69) summarized research that the therapist should adopt an open posture, lean forward, face the client squarely, make good eye contact, and remain relaxed to increase rapport. The therapist can mirror the client's body position and movements, which may help the client feel more at ease. It is possible that mirroring) communicates nonverbally that the therapist shares the client's perspective.

SELF-DISCLOSURE

Does the individual become the therapist according to the theories he or she studies or has acquired? Or, does the therapist as an individual gravitate to the theories and therapist behaviors that fit or speak to his or her already developed worldview? The therapist needs to be aware of how strongly his or her worldview determines therapeutic strategies and interventions. And, how much of what he or she does in therapy is sharing his or her personal experiences with the client. An individual already comfortable with eye contact, facial expressions, and body posture as recommended by therapy research would naturally tend to agree with the recommendations. And, become a therapist at ease with giving and interpreting such non-verbal cues. Another individual who is not intuitively versed in such non-verbal cues but more comfortable with analytical processing may be antagonistic to humanistic oriented therapy recommendations. Cognitive versus humanistic oriented individuals may be drawn to cognitive versus humanistic oriented theories and therapies, as would other individuals who may be drawn to other matching worldviews. Therapist lack of self-awareness of his or her personal process and tendencies would necessarily preclude any consideration of personal theoretical or therapeutic etiology. Consequently, therapist this also precludes any self-disclosure of his or her personal underpinnings of therapeutic preferences to the client. The therapist who fails to self-examine would have greater tendency to be theoretically and therapeutically dogmatic.

Sharpley et al (2006, page 355) cautions against rigid adherence to cognitive behavioral or rational thinking oriented therapies that focus on rational and emotional-less content and client's inability to think rationally. Beyond considering irrational thinking, eye contact, silence, facial expression, body posture, other non-verbal communications and various verbal responses (paraphrases, reflections of feelings, minimal encouragers) are necessary to engage the client and convey the genuine empathy is essential to client-therapist rapport. This the rapport that many therapists believe is critical to therapeutic success. Cognitive and humanistic conceptualizations, however along with other approaches to therapy may not be in opposition to each other. Cognitive empathy and affective empathy with the client should cross-validate to resonate for the therapist. They may be different perspectives or views of the same humanity much as there are innumerable ways to see a tree: as botany, as part of an eco-system, as an eco-system, as habitat, as economic value, as history, as art, and many other perspectives. The key may not be the technique, strategy, or theory but the therapist functioning in as real and genuine fashion within the role with a client. Human services can be conceptualized as a person offering him or herself in a relationship with another person or persons. Consideration of the minutia of characteristics and techniques or of the professional role does not absolve the therapist offering real humanity in the relationship.

Establishing rapport may include appropriate self-disclosure of personal experiences similar to the prospective client's experiences. However, self-disclosure may not be recommended by certain therapies and/or are qualified by significant cautions due to potential boundary issues. Therapist personal and professional issues affect each other in the determination of how to handle boundary concerns. While Sharpley et al cautions against rigid adherence to emotion-less content by the therapist drawn to rational therapies, a counter-balancing caution should also be made against overly personal therapist content by the therapist drawn to humanistic therapies. The responsible therapist must do considerable personal work to determine if decisions to self-disclose to clients are therapeutically sound versus indulgent of unhealthy individual emotional or psychological needs. However, Anchor et al (1976, page 158) says, "An increasing number of clinical investigators have been prompted by their findings to suggest that effective psychotherapists are capable of spontaneity, communicate that they are 'real,' reveal their three-dimensionality and implicitly invite their clients to learn through observing a credible model." The key consideration for deciding whether to self disclose is how directly it serves therapy and the client. Casual self-disclosure about a vacation or favorite food may serve therapy indirectly by building rapport through sharing the therapist's ordinary humanity, especially when the client has already disclosed something similar. Mutual therapist and client responses of Enjoyment-joy and Surprise-astonishment (identified as rapport building by Sharpley et al, 2006) are likely to occur in this type of exchange. The therapist, however should take care to evaluate this type of self-disclosure and the amount of time involved to determine if it is personally gratuitous, whether it is elicited by the client or not, may serve the client avoiding more uncomfortable and important work, or may be elicited by intrusive inquiry on the part of the client. On the other hand, certain therapist self-disclosure may directly be contributive to therapy. For example, if the wife has trouble understanding how her behavior or mood can be so vexing to her husband, the therapist may disclose a comparable personal experience.

"No one else besides my wife can have that great an effect on me. If I have a dream where my wife is cold or mean to me, I can wake up and know it's a dream, but I still really depressed! That's how much she affects me!"

The self-disclosure by a male therapist reveals to the clients the power of someone's behavior or mood on an intimate partner. In the case of a heterosexual couple, it honors the wife's importance to the husband. It also validates and gives articulation to the husband of his vulnerability and of the depth of his distress. Overall, the commonality of the couple's experience shared with the therapist's self-disclosure frames it as entirely human rather than uniquely dysfunctional. If the therapist can speak of or to the emotions of the prospective client through self-disclosure, it can enhance or deepen the client's emotional awareness and cognitive insight. And, rapport also deepens with the therapist. "Oh, you're like me in how vulnerable you are to your wife (or partner)!" and "Oh, your wife is as important to you as I am to my husband (or partner)!" Self-disclosure may not only serve empathy and commonality, "Been there, done that!" but also, give guidance for behavior change or problem solving. If the one partner complains about the other partner seeming to not really knowing her, the therapist might, for example point to a hand-carved wooden jaguar mask from Guatemala on the office wall.

"My daughter brought that back from Guatemala for me. She said she knew I'd like it. And I love it! That she knows me, means she cares to me. I love that she cares enough to pay enough attention to me to know what I would like. AND, she loves it that I love it. She feels confirmed too. I felt the same way when she loved the necklace I brought her from the Riverwalk in San Antonio."

Then, the therapist can discuss how any person in a relationship, but especially in an intimate relationship wants to feel important… that he or she "matters" to the other person. When the first partner pays close enough attention to know the other person's desires, favorites, likes, dislikes, tastes, and other nuance personal characteristics that is, wanting to “get” the other person it validates his or her value to first partner. Instead of joining in the criticism or critiquing the negativity, the dynamic is explained in simple terms based on the self-disclosure. In addition, the partner can then be appropriately challenged to first care, second commit to communicate caring, and third be guided how to behaviorally communicate the caring. Discussion about relevant gender, cultural, or other differences in behaviors of caring quantitatively and qualitatively may follow in therapy.

Self-disclosure can be a therapeutically gentle intervention to approach otherwise heated therapy circumstances. Self-disclosure as illustrated in these examples strategically removes the focus of therapy away from the partners and the couple temporarily. Instead of continuing or adding to an accusation from one against another, the therapist starts talking about him or herself (and perhaps, his or her partner… wooden jaguar mask and daughter!). Suddenly, there is no prosecutor or defendant… no claimant or plaintiff… no inquisitor or hot seat. First and second person negative dynamics and contention is replaced by a third person and fourth person (to the clients') story. Client surprise in the shift of therapy focus shifts the client, couple, or family emotional arousal to curiosity about the therapist self-disclosure. Self-disclosure can be just as effective in shifting the flow of therapy with an individual caught up in his or her distress, anger, or other debilitating psychic state. When an individual becomes immersed in his or her shame, therapist self-disclosure about a shameful experience can facilitate rapport and model behavior and strategies to get beyond shame. A raging client, who is joined by an angry therapist self-disclosing how infuriated he or she was when a car cut him or her off on the freeway can become receptive to other perspectives and consider alternative less dangerous reactions. The therapist's story of being stymied at the ignorance of so-called professionals can help the gifted adolescent realize that his or her frustration at not fitting in is not unique. Self-disclosure becomes a form of story telling. Story telling is the oldest and most traditional form of teaching in all cultures: Aesop told fables, Jesus told parables, and various wise men and women told morality tales to guide and teach. The client often relates to and finds wisdom in others', particularly the therapist's stories… also known as self-disclosure. Subsequent to self-disclosure that temporarily moves the focus from the client, therapy hopefully resumes attention to the individual, couple, or family with alternative revealed and empowering perspectives. This discussion serves to remind the therapist that while self-disclosure often occurs in the core work of therapy, it can also occur in the first contact.

PERSONAL RELATIONSHIP & HUMOR

Human services and psychotherapy, as mentioned previously can be characterized as an individual offering him or herself in a human relationship with another. Psychotherapy can further be seen as a reparative relationship with various roles for the therapist. As a result, a prospective client needs to know that the therapist is a real person and not just a role. Humanistic theoretical orientations of therapy seek to connect the humanity of the therapist with the humanity of the client. Couple or family therapy, with its greater complexity often requires very human therapists! While a prospective client usually wants to respect the knowledge, competence, and experience of the therapist, he or she often develops the greatest rapport if he or she likes the therapist. Appropriate self-disclosure and humor, especially funny self-deprecating stories can create the client experience of the therapist as being "real." As a result, the seemingly casual and purposeless chitchat or humor at the beginning of many sessions (or within the first telephone conversation) can be much more than preliminary social niceties and function to establish a sense of genuineness. Vereen et al (2006, page 10) says "Humor has long had its place in daily life. People consistently see its value in shaping their perspective in times of difficulty and in helping them to adjust to stressful situations." As Vereen et al goes on to say that the literature sees humor as a valuable tool in therapy, they also note that cultural perspectives when working with clients who are culturally diverse should influence the use of humor in therapy. Since culture can be of a larger society as well as of a single family, group experiences of humor can be relevant to understanding and relating to individual's, couple's, or family's experiences. "Humor serves as a coping mechanism when people face great inconsistencies in their creed and behavior that they cannot rationally account for or control… much of… cultural humor is motivated by the trials that they endure and that their sense of humor materializes during stressful situations as well as at the end of a crisis" (page 11). Vereen's discussion of African American humor can be applied to almost any oppressive experience shared by individuals or groups of individuals. It may be another historically oppressed or marginalized group of people, or it may be individuals who have endured the same or similar oppressions such as sexual abuse, domestic violence, bullying, adolescence, unemployment, and so forth. "African American humor, like African American music and language, is born of pain, frustration, and the human need to survive... As an expression of African American cultural heritage, humor is rich and distinctive… At any given time in history, humor documents the mind-set and social condition of African Americans… For example, during slavery humor provided comic relief from the hardships and cruelty that slaves faced… Furthermore, humor has been empowering in the midst of misery… When African Americans began to move north, they used humor to cope with the racism and discrimination they faced in various cities… Then, and even in contemporary times, humor has facilitated the venting of anger and aggression and has been used to make ironic points; it is also tied to social and political commentary" (page 11).

When an individual, couple, or family initiates or enters therapy, stress may be very high. The therapist quickly learns what the presenting issues are for the client. Within each presenting issue and/or client demographic, the knowledgeable therapist can fairly correctly hypothesize the stress and tribulations the client is enduring. The individual, couple, or family may use humor as a coping mechanism and experience. The therapist may relate with his or her own sense of humor, being intimately aware of how it helps with his or her stress. Humor can be the therapist's mechanism to honor the tension of the situation and to join the client in the awkwardness gracefully. The therapist needs to be aware of when and how humor may be inappropriate to find its therapeutic value. Humor should not ordinarily be derogatory, excessive, and timing must be appropriate. It can be used to break tension or reduce anxiety to the point where the client can address the issues, rather than to avoid anxiety and underlying issues altogether. Humor has therapeutic value to ease stress and anxiety or to bring feelings or emotions into consciousness or for therapeutic treatment. Humor can help activate underlying feelings, perceptions, cognitions, and behaviors (page 12). The client may have doubt whether the therapist really understands him or her or can relate to him or her individually. Humor helps bring people together and reaffirming a sense of kinship- that is, "I get it… been there too." Humor can be a culturally based coping mechanism for dealing with social conflicts or situations where one has little control. For example, self-deprecating humor with African American college students is a useful tool to dispel myths, break stereotypes, and build rapport. Relating humorously to some client presentations may seem difficult, but can be done nevertheless for improving therapist-client rapport. "So, did she bribe or threaten you to get you to therapy?" The therapist may find this "question" normally draws a smile if not outright laughter. It can be a funny way to reveal the reticence of a husband or partner coming to couple therapy, while honoring it. No secrets need to be held by anyone in the room: the wife, the husband, (or respective partners), or the therapist. However, this is effective only if the client experiences the therapist as genuine and congruent. Effective use of humor improves verbal expression and helps gain perspective for the client and his or her place in the greater world. Humor offers new perspectives, helps problem solve problems, and can become an effective coping mechanism.

Billie was going through the last stages of her contentious 2-year divorce process with her husband, who was still causing problems with the children. The therapist had been seeing her for a few months. Her sobriety was tenuous. Her boyfriend of the last 4 months absolutely failed her when she needed him emotionally. She was unemployed and broke. And, old memories of childhood molestation were invading her mind. The therapist went out to the waiting room and found her there on the couch, red-faced with tears streaming down her face. Her normally well coiffed blond hair was disheveled. Her normally big blue eyes were puffy and her mascara ran down her cheeks. She was in the depths of despair. The therapist said, "Hi," and waved her into the therapy room. The therapist followed her in, closed the door, and turned to her, sitting in the chair blood-shot eyes and wet cheeks, and said in feigned outrage, "Hey, you started without me!" There was a moment of stunned silence as her mouth dropped open. Then, she erupted in laughter. She couldn't stop laughing for three minutes. Now, she couldn't stop crying from laughing so hard! Divorce, hostile husband, angry children, alcoholic craving, new romantic betrayal, and molestation memories… how can any of this be funny? Beyond funny, it was outrageous what Billie was going through. There was no solution, no answer, nothing easy, nothing magical that the therapist... that anyone could offer. Life sucked big time and there were no consoling words that could change the desperation of her life. So, the therapist accepted her condition, her reality... her existential experience and offered no kind words. Instead the therapist joined with the desperation of her humanity and found a sarcastic edge. Rather than being offended, Billie found the challenge outrageous... because her situation was outrageous! It was not what she expected, but she immediately felt validated by the therapist. The therapist got it. Life sucked and desperate crying made all the sense in the world. She had started without the therapist! This was phenomenal therapeutic work- a brilliant intervention (also unplanned and an act of clinical desperation!). Billie was stuck in a morass of despair and going full speed ahead deeper into the pits. The joke broke the negative momentum of spiraling degeneration. When Billie finally stopped laughing (and hiccupping!), therapy resumed to problem-solve her life and challenges based on the humor having honored her reality.

Vereen says, "It is critical for counselors to be culturally sensitive, open, and understanding and incorporate the following tenets when using humor with their clients" (page 14). Vereen speaks specifically to African American college student, but the principles are generally relevant to all clients. Each tenet and the collection can be examined for specific relevance (such as for Billie) within the common set of presenting issues.

1. Counselors should be respectful of the uniqueness and individuality of African American college students...2. Counselors, counselor educators, and African American college students must be comfortable with the use of humor as a counseling technique…3. Counselors should earn the right to use humor. It is important that there is rapport between the counselor and the African American student client before introducing humor as a counseling intervention…4. It is important for counselors to rely on instinct to guide the use of appropriate humor…5. The intended purpose for the use of humor should be clearly defined…6. Mutual trust and respect should be apparent before using humor as a counseling tool…7. Finally, culturally sensitive counselors should work to ensure that the African American college student is open to the use of humor prior to its use.

Vereen adds, "… the multicultural value of humor in counseling… although… universal …is also culturally specific. The benefits of using humor speak to the need for counselors and counselor educators to continue to expand their own multicultural competence so that they are seen as an ally to African American college students. Counselors can use culturally sensitive humor with African American students as a tool to help students come to terms with issues in their lives, thus allowing them to see the humor that is in their present situations."

Therapists working with someone from a specific population such as African-American college students need to have sufficient personal experience with the population and a strong sense of cross-cultural competence. Personal experience in this case with African-American college students may aid in multi-cultural competence. However, cross-cultural competence requires a greater conceptualization of the attitudes, values, beliefs, and behaviors that develop to survive the circumstances of the population and experience. In the role of the therapist, there may be an inherent cross-cultural dissonance with a client whose experience may differ significantly from the therapist. An African-American college student versus the therapist of a certain ethnicity and a distinctive professional and social status presents a different cross-cultural challenge than the client Billie and the therapist with the demographics which the therapist must own. The therapist had a good sense of Billie, their rapport, and knew she was stuck in a negative emotional place and needed help getting unstuck. The attitudes, values, beliefs, and behaviors of a woman in her situation pointed to a probable mental and emotional cultural pattern that the therapist hypothesized and was familiar with from prior training, education, and experience. With all that, the therapist trusted instinct that she would respond to the joke. In addition, the therapist trusted that any reaction that might ensue therapeutically could be managed. The therapist needs to gauge client's receptiveness to humor based on rapport, instinct, and cultural competence. Sometimes, the therapist's instinct to use humor creates the right to use humor. Since any humor or any joke or any funny story can be told hilariously or fall completely flat depending on the timing, delivery, and personality of the speaker, humor should be used therapeutically by the humorous! The therapist who has a natural or well-developed sense of humor (timing, and personality) probably can use humor successfully in therapy because humor is a part of his or her genuine self. It's real for that therapist. For other therapists, forced humor or attempts at jokes may be counter-therapeutic. In other words, a funny person who becomes a therapist may be a funny therapist who uses humor effectively in therapy, but any other therapist should stick to what is genuine for him or her.

Timing and a willingness to risk the intimate connection made humor great therapy for Billie. Her set of circumstances was where she had little control- one of the situations that humor offers solace. Sarcastic, probing, yet gentle humor gave her perspective on her problems, showed her that the therapist cared, that the therapist got how awful and desperate she felt. Humor deepened the bond between them as therapist and client, and set the stage for therapy and life processes and decisions for Billie to move forward. Humor also has a simple powerful message between people. It is an invitation to play or to be playful. Playfulness makes relationships safer and eventually, deeper. Although, therapy and the therapist-client relationship is a professional relationship, it also is a deeply intimate and personal relationship. Playfulness and humor can help create the personal relationship between and among individuals within their professional roles. During the first telephone call, the client has explained at some depth the couple's issues and a hope for quick resolution in a few sessions. Therapeutic and humorous instinct caused the therapist to playfully say, "So, I'm it, huh? I gotta reverse twenty years of problems in a few sessions? Hmmmm? I think I better raise my rates!" By no means, is this a recommended standardized therapist intervention! Intuition told the therapist that the caller was full of anxiety and wanted a therapist to understand the depth of the couple's problems, but wanted him or her to be not be overwhelmed by the problems. The sarcastic response invited the prospective client to join the therapist playfully in both acknowledging the enormity and outrageousness of the request for quick results. In an instant, prospective client transitioned to a committed client with laughter and accepted the therapist's invitation to be playful. "Yeah, I need a first-rate therapist to fix a second-rate marriage but at bargain prices!" Then the therapist responded, "Oh oh, now be nice!" The conversation continued with a mixture of lightness and familiarity along with complete seriousness and commitment for the therapy. By the end of the telephone conversation with the logistics of fees and appointments worked out, the client's voice resonated with excitement and hope saying they looked forward to the first session.