7. Partner/Relationship Characteristics - RonaldMah

Ronald Mah, M.A., Ph.D.

Licensed Marriage & Family Therapist,

Consultant/Trainer/Author

Main menu:

7. Partner/Relationship Characteristics

Therapist Resources > Therapy Books > SorryNotEnough- Infidelity-Cpl

Sorry is not Enough, Infidelity and Betrayal in Couples and Couple Therapy

Chapter 7: PARTNER & RELATIONSHIP CHARACTERISTICS

by Ronald Mah

Couples that come to therapy with a primary issue around infidelity of one of the partners, nevertheless present in a variety ways that alter the direction and strategy for therapy. The partners may be leery about the possibility of recovery from infidelity. While willing to try couple therapy, one or both partners may assume or fear that the relationship might not survive the trauma of the affair. In the process, each partner needs to determine both his or her and the partner’s commitment to the relationship. While both may be committed to maintaining the relationship and healing from the affair, they also must be committed to addressing and changing underlying issues and interactions that influenced stepping outside the monogamous relationship. If they can do this, there is the potential that the relationship will not only survive, but also become stronger and function with greater integrity. The partners may have entered into the relationship under the assumption that fidelity to one partner is the social norm and then, stunned to have to deal with straying eyes that lead to straying fidelity. Partners often have conflicting influences from the beginning of the relationship that they would have been well advised to address previously.

The therapist needs to be aware that contrary to the stereotype, women may be as likely to start an affair as men. For example, although the focus here has been on Aidan and Cathy as the affected couple with Aidan being the unfaithful partner and Tina the affair partner, in actuality Tina was also married. Thus she was not a free agent romantically who happened to choose a married man for a sexual relationship. She is also an unfaithful partner to her offended husband. Between Aidan and her, she was the initial aggressor seeking first emotional intimacy and then a sexual relationship. In historically traditional male dominated societies, women may have had few if any options than to stay in a marriage. Women’s ability to survive or function successfully on their own in their community may have been limited at best. As such, potentially losing social status, economic support or wherewithal, and physical security by being involved in a relationship outside the marriage would have been highly counter-indicated. In modern societies where political, economic, and legal protections are stronger for women, having an affair risks “only” the loss of the relationship or marriage. It does not necessarily endanger the financial and physical security of women as it had in prior times and societies. Francine for example is not dependent on a man’s benevolence much less his income as a modern educated professional American woman. She can and did betray multiple partners and have frequent affairs. Without historical limitations created by her female gender, Francine does not risk stoning or being ostracized by the community. In fact, depending on the social circles in which she functions, she may gain greater notoriety and subsequent power and influence.

RELATIONSHIP STABILITY, LOGIC, AND FIDELITY

When infidelity is uncovered, the offended partner and others may be shocked thinking that there had been no indications that anything was wrong in the relationship. This is based on the assumption that relationship stability assures fidelity. Inexperienced and unaffected individuals often see an affair as the outcome of deep problems in the relationship or marriage. While this may be relevant in many relationships, it is not unusual for the unfaithful partner to claim that the relationship or marriage and sexual intimacy and passion had been very satisfying. None of these issues, therefore were the reasons for infidelity. If asked, neither Aidan nor Cathy would have had any substantial complaints about their relationship, or had any concerns about an affair occurring. The marriage or relationship may be highly functional by all respects as acknowledged by both partners. In Aidan and Cathy’s case, there would have been agreement by just about anyone: friends, family, and colleagues about the stability of their marriage. In addition the unfaithful partner may assert that sexual intimacy outside the committed relationship has enhanced both the relationship and the sexual satisfaction. Rather than inadequate frequency or unfulfilling sex or the offended partner withholding sex or emotional intimacy, the unfaithful partner may acknowledge greater sexual intercourse and emotional connection in the committed relationship concurrent with an affair. Although, Cathy was highly skeptical and simultaneously fearful that her and Aidan’s sex life had become pedestrian, Aidan was adamant that his sexual arousal, interest, and satisfaction with Cathy was at least the same before and during the affair.

The continued potential exposure to sexually transmitted diseases (STD) and in particular, to acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) can be considered an inhibitory factor to extramarital or sexual affairs outside the committed partnership. The offended partner such as Cathy may intensely interrogate the unfaithful partner repeated whether the affair sex used prophylactic protection against infection. Failing to engage in safe adulterous sex would be an additional betrayal- that is, to potentially expose the offended partner to sexually transmitted diseases. However the possibility of contracting a STD does not inhibit infidelity. “Statistics do not support this. Not only did AIDS not reduce infidelity, in fact less than one-half of individuals reporting sex outside the marriage use safe-sex with their primary and secondary sex partners” (Zur, 2012). Being exposed to social ridicule, vocational impediment, career destruction, and anger of family members, especially ones children would also seem to be effective inhibitions to preclude infidelity. However, anticipating the possibility of these consequences has clearly not been sufficient to prevent very successful and intelligent individuals from having affairs. Any survey of any historical period finds such individuals not only committing infidelities, but also getting caught, exposed, and suffering devastating personal, financial, social, political, and career consequences. Intelligence or logic as commonly held proves insufficient for many individuals to prevent lapse into infidelity. This apparent irrationality adds to the anger and confusion of the offended partner especially when the unfaithful partner is clearly an otherwise intelligent, worldly, and duly cautious individual.

RELATIONSHIP QUALITY

Other key motivations must be considered along with issues about the relationship. Underlying the Cathy’s shock about the affair were her assumptions about the quality of their relationship. She thought it was a mutually beneficial volitional relationship of secure commitment, affection/love, and respect. It was the relationship she wanted and what she thought Aidan also wanted. She was clueless as to what could have motivated Aidan’s infidelity. Bagarozzi (2008, page 15) offers seven motivational considerations for each partner for the therapist to consider in formulating therapeutic strategy.

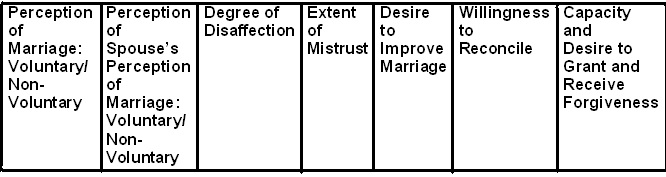

TABLE 3 Motivational Considerations for Each Spouse

The therapist gathers information about potential motivations for infidelity and also about recovery and healing. Investigating the relationship will normally uncover other important relevant influences. The partners need to examine the condition of the relationship not only after discovery of the affair, but from throughout the partners’ history. The evolution or progression of ones motivation may vary significantly compared to the other partner’s. Each partner’s description of the trajectory of the couple’s intimacy and dynamics conveys a personal experience. The two renditions of the relationship story may be largely in sync but almost inevitably will have significant discrepancies. The relationship stories moreover do not start when the two partners first meet. The pre-history from the family-of-origin and prior life and relationship experiences are incorporated into their relationship stories. The “back story” may be as critical to eventual choices as the committed relationship or marriage. In fact, the committed relationship may be a sequential/progressive chapter in a longer life odyssey. The infidelity may be part of a deeper personal pattern of betrayals, deceptions, or dysfunction. Individual traits and tendencies may have foundations deep in their experiences and manifest in unexpected, surprising, and impactful ways.

Cathy had developed carpal tunnel in her wrists from hours and years at the computer keyboard. She became fully occupied dealing with the pain, while raising children and working. She was officially the development officer at her non-profit organization. In actuality, she did just about everything they needed, especially if it meant writing: marketing, public relations, grants, policies and procedures, and so forth. There had been pressure on everyone in the non-profit from losing funding and having to do more with less human resources in tough economic times. Cathy was a good writer and had a long, skilled, and diverse background in the financial world and the human services world. Her combination of experiences made her an invaluable major contributor to the non-profit. Years of pounding away on the keyboard and working through pain and discomfort to meet deadlines had taken a toll on her physical well-being. There were neck pain and backaches, but the worse was the wrists. Someone had to do it, and that someone who could do it well and correctly was Cathy. Everyone turned to her, and she could not let them down.

This was a part of her work ethic as part of an immigrant family. The family business was import and sales of any number of goods. Later there was the storefront and the warehouse for the wholesale business, and eventually the work crews to manage as well for delivery and servicing equipment. Cathy’s dad was an entrepreneur of and from the old country. That meant that Cathy and her siblings were the first and depended upon workforce. If it had to be done, family would get it done. Cathy’s older brother was however groomed to be the educated one and he was allowed to prioritize academics. It fell upon Cathy as the second oldest to organize and sometimes, drive the other siblings to get the work done. Her brother and Cathy were children of new immigrants born within a couple of years of arriving in the United States. There was a four-year gap before the other three siblings: two boys and one girl were born- each a year apart. They were the “American” siblings and clearly were less driven to work in the family business. They were more attracted to the fun and games of the American kids. Cathy often felt she had to compensate for their lackadaisical attitudes and efforts to get things done.

“Getting it done” was her mantra. Calculating the personal cost in terms of energy or potential loss was not a part of that ethic. Supporting Aidan in his career was a part of getting it done. Bearing and raising the kids was too. Getting the report done, the grant submitted, preparing for the inspection, and building the non-profit was what she demanded of herself. Calculating the costs of working through the pain in her wrists was not her way any more than it had been Aidan’s way. Eventually, the cost to persist through everything affected her relationship with Aidan just as his work world rose to another level of stress. Upon reflection in therapy, Cathy saw that she had always been Aidan’s confidant about work and life challenges. Aidan turned to Cathy for her perspectives and support when he pondering whether to leave the corporate world to join the family foundation. When there was the disruption of the foundation transitioning from his mother’s leadership to his officially taking on the CEO position, Cathy was always available to discuss his thoughts and feelings. Both partners largely verified their respectively experiences of the relationship. At the same time, Cathy’s attention focused on work demands while balancing her carpal tunnel pain, Aidan got into major work turmoil with staff and his board of directors. At this point their respective relationship stories diverged.

Cathy consciously prioritized getting the childcare tasks and her non-profit work done, while subconsciously assuming that Aidan could take care of himself. For the first time in her life, Cathy found that she could not do it all. The physical pain was too much. She assumed unconsciously that Aidan could handle it- that is, handle her prioritizing her self-care and obligations. He was a strong person with high morals and integrity that she had experienced in many ways for over twenty years together. Aidan had taken Cathy’s support for granted to the degree that he did not know how much he depended on it. Being oblivious of female partner support is not unusual for some men who benefit from the partner’s actions without being aware of it. The pattern of their interactions when Aidan had a lot on his mind was not so much Aidan seeking advice and support, but Cathy noticing subtle cues of Aidan being a bit out of sorts. Cathy would engage Aidan about what was going on, and he would disclose his challenges. Cathy did not see the cues during this period because of her enduring a pervasive haze of stress and pain. Aidan’s habitual stoicism and compartmentalization precluded any substantial overt or assertive requests for Cathy’s attention. Without facilitative and supportive interactions with Cathy to release negative energy, his instincts to compartmentalize caused him to load up on emotional, psychological, or spiritual stress over the months. Many men do not notice the presence of female support, but will notice its absence or when it is withdrawn. It may not be a fully conscious awareness with insight, but a sense that something is “off” or not quite right or things have somehow changed. Aidan however was somewhat oblivious to the support when he had it and when he lost it. Unbeknownst to either partner, this created Aidan’s vulnerability to Tina’s advances. Only upon care reconstruction did the partners realize that their relationship had devolved fundamentally during that period despite twenty plus years of fidelity, love, and mutual respect.

An affair or revelation of infidelity that brings the couple into therapy is often only the latest plot twist in a longer relationship narrative or in two parallel relationship stories. Each partner’s perception of the relationship evolution and current condition influences how he or she approaches couple therapy and the attempt to resolve infidelity in the relationship. The therapist prompts the individual who has breached fidelity to describe his or her sense of intimacy, sexual, spiritual, and other qualities of satisfaction from initial through early, middle, and most recent periods in the relationship. The affair and relationship takes on different qualities depending on how recent versus enduring dissatisfaction has been for the individual. Or, the therapist has important additional inquiry to conduct, if the individual committed infidelity despite professing relative satisfaction. The offended partner also should describe his or her degree of and changes in satisfaction. The therapist may find that one or both partners were from completely ignorant or completely attuned to the others sense of fulfillment in the relationship.

Being a couple is assumed to be a mutual decision based on mutual reciprocal benefits. These in turn are based on some combination of romantic, spiritual, religious, cultural, social, to practical considerations such as finances or raising children. Depending on how intensely bounded a partner is to such benefits or values, he or she may feel staying in the relationship mandatory rather than volitional. Modern romantic notions of relationships and marriage assume that each partner is equally empowered to choose to be in, stay in, or leave the partnership. American social and cultural values and law give each person rights to choose his or her partnership (although not marriage with legal restrictions against same sex marriages in most states as of 2013- the time of writing this book, or against potentially exploitive relationships based on age differences or possible vulnerabilities). However, the subjective reality of each individual may vary significantly based on personal, religious, cultural, or social beliefs and values. The subjective reality may create limitations that restrict free choice and cause the individual to feel stuck in a relationship or marriage. Subjective restriction may be based on real world issues such as financial dependence or social status or acceptance/rejection. Or, it may be based on values and beliefs such as marrying for life, prohibitions against divorce, or staying together for children. There may be more emotional or psychological barriers to leaving the relationship such as being adverse to admitting failure or fear of being shamed. The therapist needs to explore both functional and subjective experiences of how voluntary each partner feels staying in the relationship may be versus how stuck he or she feels. Loss of choice or feeling helpless or lacking power and control can lead to a sense of deprivation for the individual. A sense of deprivation may lead to a sense of entitlement resulting in gratuitous behavior such as addiction and infidelity. Choosing sex outside the oppressive relationship becomes justifiable and reasonable for someone who feels entitled as a consequence of feeling deprived.

COMMITMENT: FACILE, DESPERATE, UNQUALIFIED, & QUALIFIED

The therapist needs to assess for each partner’s commitment to the relationship or marriage. “A higher level of commitment to the relationship may lead couples to work harder in treatment and to be more willing to engage in emotional risk-taking within therapy; however, an initial ambivalence about the relationship is not necessarily a prognostic indicator of treatment failure. Ambivalence at the beginning of treatment does not preclude the couple's ability to try to improve and understand their relationship in order to come to a good decision about whether to continue with the marriage and in fact is often quite understandable in light of the presenting issue. It is often helpful to frame this ambivalence as such in order to normalize these feelings” (Baucom et al., 2006, page 384). Each partners’ respective commitment to the relationship versus to resolve the infidelity must also be assessed. The therapist should not assume commitment as a given. In fact, the process of clarifying commitment level is already provocative. “Attempting to exact an agreement of commitment to the marriage runs the risk of triggering a flight from treatment, or at the very least giving superficial agreement to the therapist, and hiding the underlying ambivalence and turmoil from the therapist” (Moultrup, 2003, page 269). There is often a great deal of ambivalence for both partners. The offended partner may not be sure if he or she wants to continue or even try to recover and heal. The unfaithful partner may not be sure if he or she still wants to make it work or if it is worth it. Either or both partners may also be ambivalent about whether therapy can work and/or if the therapist is competent to facilitate recovery and healing.

When they started couple therapy, Aidan was deeply committed to staying together and restoring the marriage. However, he was not necessarily committed to or had confidence in the process of couple therapy helping that happen. Aidan felt his absolute commitment and resolve to never transgress again was sufficient. He already had certainty so couple therapy did not offer developing commitment and resolve. Coming to therapy was a sign of being committed to do anything that Cathy needed to recover and heal. Cathy was not confident about or committed to couple therapy either. She hoped it would be productive and help their process. She was definitely not committed to continuing the marriage and reconciliation. She was not sure. Attempting couple therapy was an experiment both to see if the process could be effective, and especially to find out if she could tolerate a process of investigation and exploration. Before committing to trying a recovery, healing, or reconciliation process, Cathy needed to see how Aidan would react. If he stonewalled her needs for understanding, details, transparency, and introspection, she was likely to give up. Then there was what he might say about the affair, the affair partner, her, himself, and their relationship. Even if Aidan was a conscientious dedicated participant in couple therapy, she still needed to see if that was enough for her. Cathy was not sure if she could stand Aidan anymore or if she could endure the raw pain required for the process. Commitment was a developmental process that needed time and experiences without any certainty of it occurring or deepening.

The therapist must be aware that commitment to the relationship may not include commitment to resolve the infidelity. The individual who has committed adultery or has sex outside the monogamous relationship may want to stay together but may want very little to do with examining his or her infidelity. Aidan for example, was reluctant to attempt introspection, reflection, and seek insight about himself and his infidelity. This was not a defensive or avoidant reaction due to guilt alone, but a life long personal decision. Aidan felt moving on after each crisis or challenge without evaluating it was prudent. Considering or obsessing about what had happened- in particular, the emotional, psychological, and spiritual consequences of having dealt with the crisis, and effects on personal or professional relationships complicated taking on subsequent tasks. He wanted to work on healing and solidifying the relationship, not reliving the dysfunctional past. Like many other unfaithful partners, Aidan made a commitment to monogamy, swore not to transgress again, expressed awareness of wrongdoing, love for the partner, and claimed to absolutely know his mistake. Asserting knowledge and commitment to a boundary, that the unfaithful partner had always known and had committed to previously does not resolve the infidelity. Prior knowledge and commitment had not worked to prevent infidelity, so reasserting it does nothing to gain any understanding or change to prevent the identified monogamous boundary being bypassed once again. The offended partner knows this instinctively, although may not have been able to articulate it.

The offended partner may desire the relationship so desperately that he or she may be willing to accept such a facile commitment. In fact, infidelity or the issues underlying an affair, including avoidance may have been what the partners had previously colluded on to not address for some time in the relationship. In addition, the therapist should also be wary that commitment to resolve the infidelity might not include a matching commitment to staying together as a couple or in a marriage. Dealing with the affair may be about resolving pain and hurt, understanding the relationship, making a case against and punishing the betrayer, or preparing to or being enabled to leave the relationship. As such, resolving the infidelity rather than serving to enable the partners to stay together facilitates terminating the relationship. Couple therapy changes fundamentally as a partner works toward such implicit goals that may be contradictory to the expressed goals of the other partner or those given to the therapist.

The therapist needs to also bring out what each partner’s perceptions about how the other partner believes or feels he or she may be stuck in the relationship. Each partner may have a sense of choice or not about being in the relationship or marriage. Commitment may be related not only to a sense of volition but also related in various ways to a fear of intimacy as well. “Attachment theorists describe a pattern of attachment that is characterized by approach-avoidance (e.g., Hazan & Shaver, 1987). Individuals with this pattern may need intimate relationships and seek them out. Yet, they may also fear them to such an extent that they find it difficult to feel safe in long-term intimate relationships. Affairs may then serve as a means to create a safe level of distance from their partners (Allen & Baucom, 2004). In this case, the participating partner may need adjunctive individual treatment targeted toward this issue before the couple's relationship is able to recover “(Baucom et al, 2006, page 384).

Intense emotions may not be of attraction or love but come primary from attachment anxiety. The desperate need to have an intimate other can be a part of the unfaithful partner or of the offended partner. The unfaithful partner may maintain an unfulfilling relationship from fear of losing the attachment partner and have affairs to compensate for a lack of true intimacy. Or, seek reassurance of being valued by seeking out-of-relationship partners. Therapy would need to explore attachment issues for both partners. Aidan suffered a significant attachment loss when he was very young when his sister Hilary left for college. There was a possibility that attachment issues affected both his bond with Cathy and his vulnerability to infidelity. Unfortunately, Aidan was unable to access memories or feelings about this time in his life. Nevertheless, the high probability of attachment trauma from losing his primary attachment figure remained under consideration in understanding Aidan’s makeup.

Aidan had been a “miracle baby,” who arrived unexpected and unplanned when his parents were older. They thought they were done bearing children. They had anticipated and were actively moving into their post-children “play-work years,” when the miracle baby came along. Aidan had three siblings that were sixteen to twenty years older than him. His sister Hilary who was sixteen when Aidan was born, cared for him more than his parents. The parents laughed about “Hilarymom” being more his mom than his mother, but it was very real for Aidan. Hilary fed him, changed his diapers, dressed him, soothed him when he cried, taught him how to walk, taught him how to say “doggy,” played with him, and most of all loved him. Aidan followed her around all the time. If his mother or father had any struggle soothing him or figuring out what he needed or wanted, they turned him over immediately to Hilary. Hilary went away to college when he was barely two years old. Aidan claimed he did not remember Hilary leaving, or being upset that she was gone. The therapist explored this experience extensively in the couple therapy. It made no emotional sense that Aidan suffered no distress- did not become desperate with the loss of Hilary who was his primary attachment figure.

Aidan expressed great respect for both his parents, their dedication and achievements, and professed love for them. He spoke of their modeling dedication and purpose in life. His words of respect and love were quite clear, but his affect lacked the vibrancy he exhibited when speaking of his attachment/love for Hilary to this day. His lack of memory and emotional intensity about the separation loss of Hilary suggested that he had compartmentalized or disassociated from the extremely traumatic experience. Compartmentalizing his feelings was an overt skill and strategy that Aidan found productive in his professional work. Aidan said there were a lot of battles within the organization, with political rivals, funders, and government agencies with a variety of well-intended to egotistical to corrupt individuals. Compartmentalizing his feelings allowed him to move onto the next challenge without accruing loads of resentment that would compromise his effectiveness. He did not consider how much anything cost him physically, emotionally, psychologically, or spiritually. His work ethic and sense of self was to do what needed to be done, and then move on to the next task. It had worked well or well enough for him up until shortly before the affair.

The offended partner may tolerate a limited emotional intimate relationship to have someone around however inadequate, rather than have no one. The offended partner may also commit to staying together despite it not being and in all probability never becoming a fulfilling intimate relationship. For both such partners, they may feel stuck in the relationship not for financial, social, or child-rearing reasons but for attachment needs. Each partner in therapy can hear about the other partner’s level of commitment to the relationship or marriage and makes a judgment as to its veracity. Attachment anxiety or despair-founded commitment may motivate staying together. However, the integrity of the relationship may not be ever wholesome. The therapist may need to work through layers of issues to bring the relationship to a stable healthy state. The partners may not be able or willing however to address these issues and be satisfied with being together. Therapy may shift to dealing with another layer or aspect of trust issues when one or both partners doubts the others expression of choice and commitment to be in the relationship or marriage.

The therapist may need to confront implicit suspicions to bring them into therapy to be addressed overtly. The offended partner may however say he or she believes that he or she does not feel stuck in the relationship and moreover, is committed to heal injuries from infidelity and heal and build the relationship. This confidence may not feel justified to the therapist and/or the trust feel genuine. The therapist should challenge the offended partner as to why he or she trusts the individual who has already betrayed previous trust with infidelity. Trusting someone whose betrayal has just been uncovered is counter-intuitive and against logic, particularly shortly after the uncovering of the affair. Such disingenuous trust may be indicative of emotional, psychological, spiritual, and intellectual weaknesses or flaws in the offended partner. These need to be addressed for a recovery process of integrity. Conversely, such trust may at another time be appropriate, earned, and a sign of ego strength. It may be indicative of emotional, psychological, spiritual, and intellectual strengths in the offended partner, the unfaithful partner, and the couple that may be drawn upon in a healing process.

VOLITION & SATISFACTION

Using a bipolar separation of characteristics: high versus low relationship satisfaction, voluntary/volitional versus non-voluntary nature of the relationship, and high versus low commitments gives eight (2x3=8) potential perceptions of the relationship. These eight perceptions are expanded if median characterizations are included: medium satisfaction, partially voluntary, and medium commitment (3x3=27 potential perceptions). In addition, since commitment to saving or maintaining the relationship is not always matched with commitment to dealing with the infidelity or commitment to the partner, there are additional variations that the therapist may encounter. This model produces further relevant perceptions if each partner also looks at the initial period, early periods, middle periods, recent periods, and the current post-revelation of infidelity period of the relationship. The following are some perceptions that may be relevant to the couple and couple therapy.

I. Satisfying (prior to affair), voluntary, committed to one’s spouse, committed to improving the marriage and to resolving the infidelity.II. Unsatisfying (prior to affair), voluntary, committed to one’s spouse, committed to improving the marriage and resolving the infidelity.III. Unsatisfying (prior to affair), voluntary, not committed to one’s spouse, not committed to improving the marriage or resolving the infidelity but no better alternatives to marriage are perceived to be available at the time.IV. Unsatisfying (prior to the affair), voluntary, not committed to one’s spouse, not committed to improving the marriage or resolving the infidelity but better alternatives are perceived to be available. Person plans to leave the marriage.V. Satisfying (prior to affair), non-voluntary, committed to one’s spouse, committed to improving the marriage and to resolving the infidelity.VI. Unsatisfying (prior to affair), non-voluntary, committed to one’s spouse, committed to improving the marriage and resolving the infidelity.VII. Unsatisfying (prior to affair), non-voluntary, not committed to one’s spouse but committed to maintaining the marriage and improving the relationship without necessarily resolving the infidelity.VIII. Unsatisfying (prior to affair), non-voluntary, not committed to one’s spouse but committed to maintaining the marriage with no desire to improve the relationship or to resolving the infidelity (Bagarozzi, 2008, page 7-8).

The therapist that knows infidelity has brought the couple into therapy does not yet know enough to conduct effective work. Among assessment requirements are level of relationship satisfaction, respective commitment by each partner to the relationship and/or each other, and other overt or covert issues affecting being stuck or choosing to stay in the relationship. The personal experience of each partner of the relationship quality, his or her relative role and power and control, and his or her sense of the partner’s desire to work out the cause and repercussions of the affair set the stage for the therapy and potential recovery. When both partners perceive the relationship history and current condition basically the same way, then therapy is often a simpler process. However, if there are fundamental differences in perception, therapy is more complex and recovery may be less likely. For example, if the unfaithful partner was unsatisfied in the relationship, chosen to be in it, but is not committed to the partner or resolving the relationship or the infidelity, he or she may next consider if there are alternatives. On the one hand, the individual may not see any viable alternatives, or he or she may see or have an alternative that motivates plans to terminate and leave the relationship or marriage. If he or she further knows that the other partner sees him or herself as stuck in the relationship, there is little or no motivation to stop the infidelity, agree to participate in couple therapy, or if in therapy, to be actively involved.

In contrast, the unfaithful partner who like his or her partner, although feeling stuck was satisfied in the relationship and committed to the relationship, partner, and resolving his or her infidelity will be willing and invested participants in couple therapy. The therapist is able to further activate both their commitment and investment and the likelihood of healing and recovery from infidelity and relationship survival increases. Partners, who both had found the relationship unsatisfying but felt compelled to stay in it, and were committed to each other and the relationship as well as resolving the infidelity, may have increased probably for successful resolution. The therapist would work from the commitment foundations and work on both resolving infidelity and the lack of satisfaction in the relationship. It is reasonable conceptually that relationship dissatisfaction share the same or related underlying issues with the infidelity. Addressing and resolving these issues for committed partners offers a positive prognosis.

If partners who are not committed to each other, nevertheless mutually agree to stay together with or without seeking qualitative improvement in the relationship, the therapist is charged with managing a “business relationship” based on functionality rather than romance or intimacy. Therapy or the couple’s negotiation would revolve around shared habitation, financial needs, and child raising demands among other functional issues, while keeping out of each other’s way emotionally and socially. There may be negotiation of boundaries for each partner meeting his or her intimacy, emotional, or social needs within their business-like relationship or marriage. Avoiding open conflict in a kin of cold-war truce becomes the goal of the couple, rather than developing greater connection and intimacy. The therapist once again should be wary of his or her own romantic or psychological values versus the functional economic expectations in committed relationships or marriages. The goal of “making it work” may be limited for some partners. The therapist should take care not to impose a goal of mutually fulfilling romantic, child-rising, intellectual, emotional, and spiritual partnership on such a couple. He or she may point out the potential limitations and expanse of relationships as the partners identify their expectations, but should adhere to their goals whenever possible.