13. Competence - RonaldMah

Ronald Mah, M.A., Ph.D.

Licensed Marriage & Family Therapist,

Consultant/Trainer/Author

Main menu:

13. Competence

Therapist Resources > Therapy Books > Mirror Mirror- Self-Esteem Relationships

Mirror Mirror… Reflections of Self-Esteem in Relationships and Therapy

Chapter 13: COMPETENCE

by Ronald Mah

"A person strives to feel capable, to feel he or she will grow and develop. This striving begins in childhood where feelings of inferiority to tasks and to bigger more competent individuals abound. A child learns to compensate for feelings of inadequacy, striving to develop abilities and talents. As young people grow and mature, they increase their knowledge, skills, and abilities and find a place in society where they can feel competent and independent" (McCurdy, 2007, page 283). The more a person feels competence in areas that he or she finds important or is invested in, the more self-esteem the person gains. People's areas of desired competence vary a great deal. There are significant cultural variations, plus strong influences by family, peer, and social models. Being a good parent, a good provider, pleasing ones partner, and so forth support self-esteem if those goals are what the individual in a relationship desires to achieve. Sometimes the areas that one individual seeks competence in order to fulfill the other person's desires or needs may not be what the other person actually wants. For example, men who feel being competent as a provider financially fulfills both their own needs and their partners' needs, may be discouraged or even angered to find it insufficient for their female partners. "…women and men are concerned about different aspects of relationships. For women, marriage is defined by relationship and intimacy. Men seem to focus more on competency. Each gender's experience of shame or alienation seems to have the strongest relation with that aspect of relationships it prizes most. Women report that shame and alienation are more highly related to perceptions of intimacy, and men report that shame is more highly related to perceptions of competency. Fear of intimacy and low levels of interpersonal competency may be driven by internalized shame, indicating a need for shame-related treatment to increase competency and intimacy "(Blavier and Glenn, 1995, page 80). Seeking competency includes in pleasing the important other person in ways relevant to that person's values. Male hierarchal instincts to achieve dominance may inadvertently result in shaming or alienating female intimates. Rather than appreciating the dominance or performance competency behaviors of the male, the female partner may find him incompetent as far as promoting intimacy.

The individual intuitively understand that his or her partner or person in an invested relationship wants to do things well. They struggle to make something work. Each individual is challenged by tasks in the relationship. Each individual wants to be competent in doing relationship things. Both individuals such as Terry and Bert wanted to be competent communicating, collaborating financially, raising children, creating a home, playing together, planning retirement, and so forth. The list of desired collaborative competencies were reduced but not eliminated by divorce. The more competent the individual is at what he or she deems important to be competent at, the greater his or her self-esteem. Incompetence in areas of no interest or little investment, on the other hand does not particularly affect self-esteem one way or the other. What are the areas of competence each member seeks relative to being in a relationship, couple, or a family? Are they meaningful for the other person? The therapist helps the individuals in the relationship articulate these areas of desired competence, helps match them to the needs of both members, and helps facilitate new competencies to meet desires of each member.

Partners need to learn how to function not just as a couple, but how to function socially as a couple in the larger community. Family members need to learn how to function as family at home and socially in the community. Or, group members learn to collaborate as a team, work crew, and so on, and in larger contexts such as against other teams, business rivals, or with other agencies for example. Any individual that has trouble fitting in and following relationship, couple, family, or group rules and expectations draw disapproval from the community (friends, family, and even strangers). The partner of a social inept partner picks up on the disapproval from others. Recognizing social cues and idiosyncratic social behaviors can constitute social emotional competence in relationships. Failures in with social interactions, understanding and being understood by one another, and in developing intimacy can be fundamental incompetencies. An individual may be challenged to be competent relating to someone with significantly lesser abilities, different social or emotional awareness, qualitatively greater emotional intensity, or highly different interests. An individual may be both or either hyper-competent or hypo-competent in different areas compared to the other person. The individual often expects his or her partner, family member, and sometimes colleague to be attuned to and competent at soothing him or her when distressed. If the other person is not aware or able to soothe appropriately, the individual may feel him or herself ignored or perceived as unimportant to the other person. The individual's self-esteem is harmed. The other person may get resentment from the individual and may respond with defensive behavior. He or she may flip the anger by blaming the individual for not being okay, effectively punishing the individual for needing soothing. This dynamic can be even more dangerous for men, since there are cultural forces directing them to avoid their feelings.

Sometimes an individual's discomfort with another person's pain and distress is not about some cultural or other bias, but from concern that the pain and distress may becoming overwhelming or dangerous. However, treating a person as if he or she is not competent to handle pain and other stresses causes problems as well. It implies that the person is too fragile to handle difficult emotions. The competence to handle powerful emotions like fear, anxiety, sadness, and disappointment comes from allowing and suffering the struggle. The therapist need to carefully consider how much to intervene and how much to hold back, what is too much support and crippling, and what not enough and rejecting or abandoning. This is true for an individual considering how to challenge or confront the other person as well. Finding competence requires testing it. Being skillful and becoming competent in the areas that become important to oneself in a relationship often depends on deeper levels of emotional and psychological soundness/competence. When an individual finds competence handling difficult emotional experiences, then competence handling other tasks becomes easier. Feeling competent or feeling okay for any individual in a relationship is strongly dependent on the other person feeling competent, feeling okay as well.

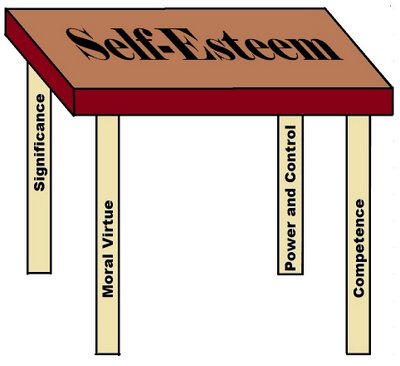

"When an individual believes in his or her partner's capabilities, he or she feels competent about them both, as a couple. He or she sees positive alternatives to seemingly overwhelming problems (Dinkmeyer & Carlson, 1985). Partners who believe in each other's capabilities are committed to each other's growth as well as to seeing the relationship grow and flourish (Blanton, 2000; Sharpley & Kahn, 1982). A partner who does not feel competent may try to control the other partner or become dependent on the other, seeking to meet the mistaken goal of power. The relationship becomes one of inadequacy. Individuals who do not feel their partner is competent may find themselves playing the 'I'm right: You're wrong!' game or the 'I don't want to discuss it!' game (Mozdzierz & Lottman, 1973). In this instance, a counselor can use an intervention called a 'time out,' which is similar to the Adlerian technique of 'spitting in a client's soup' (Sweeney, 1998). A couples counselor is often referred to as a referee, so exercising a time out is an appropriate strategy when a couple begins one of these two games. The counselor simply calls a time out and brings to each partner's attention the game that is being played and to each partner's role, effectively" (McCurdy, 2007, page 286-88). The therapist can challenge everyone about how they seek to be competent in the relationship. One individual's attempts at relationship competency may not meet the other person's needs. When therapy reveals the mismatch, problem solving teaches the first individual to provide as the second person desires, and teaches the second person to appreciate the positive intent of the first individual. The process is then reversed. If the individual or each person's sense of competency were flexible, therapy would be relatively simple matching behavior to desired outcomes. Inflexible competency definitions that complicate problem solving and the relationship became a focus of therapy. These would be from an individual's ideal self definition. Significance, moral virtue, power and control, and competence are each important, but also are highly interdependent.

These four components of self-esteem are very much like the four legs of a table. All four of the legs need to be strong, or else the stability of the entire table is harmed. If any one leg is weak- that is if any aspect of self-esteem is weak, no matter how strong the other three legs, the table or self-esteem will not be solid. The therapist needs to help each individual, couple, and family establish and solidify all four aspects of self-esteem.