2. The Second C- Credibility - RonaldMah

Ronald Mah, M.A., Ph.D.

Licensed Marriage & Family Therapist,

Consultant/Trainer/Author

Main menu:

2. The Second C- Credibility

Therapist Resources > Therapy Books > Therapy Interruptus

Therapy Interruptus and Clinical Practice,

Building Client Investment from First Contact through the First Session

Chapter 2: THE SECOND C- CREDIBILITY

by Ronald Mah

• Clients may have differential gender expectations around formal and informal attire and office décor.• Positive therapist energy may be attractive to clients.• Eight elements to consider in an office setting: (a) accessories, (b) color, (c) furniture and room design, (d) lighting, (e) smell, (f) sound, (g) texture, and (h) thermal conditions.• Personal comfort of the therapist may be the best guide to attire and office décor decisions.• Therapist personality expresses in office design and can be a part of therapy.• Clients prefer therapists who demonstrate they are competent, knowledgeable, and experienced about the presenting issue (depression, anxiety, infidelity, academic problems, etc.) or the treatment modality: child, individual, couple, or family.• Topic-Initiation Therapist responses, particularly Topic-Reintroduction responses tend to build rapport better than Topic-Following responses.• Therapists who respond with integrity, honesty, and professionalism to client questions and behaviors are responding appropriately to client therapeutic boundary issues.• Initial Therapist credibility based on referrals and credentials require subsequent appropriate therapist responses to client presentations.• Active early therapy including interventions such as interpretation build rapport.• Building the therapeutic relationship should take precedence over information gathering in early therapy.• Therapist responses to client presentations that show depth and insight build credibility.

The client may gain immediate positive or negative impressions of the therapist's credibility based on any number of factors. "If indeed initial impressions of a psychotherapist or counselor influence a client's willingness to return for further sessions, the identification of the specific factors that contribute to these impressions would be of practical significance with respect to a wide range of therapy settings" (Gass, 1984, page 56). For private practice practitioners, early departure of a client for any reason or a prospective client who does not invest in therapy can have major financial and business consequences. In private practice and in agency situations, the integrity of the therapy can be compromised if clients do not find the therapist a credible professional and a potential aide to their needs. Subjective likeability or attractiveness may affect rapport and whether clients choose to stay in therapy. "30% to 60% of therapy clients terminate within the first six sessions with or without the therapist's approval. The figure is even more dramatic for outpatients of lower socioeconomic status, who have a dropout rate that exceeds 50% after the initial interview… Problems with attrition and the development of an effective working alliance sometimes may be attributable to the client's perception of the therapist as unlikeable, insufficiently trustworthy, or incompetent. In support of this, studies have found that communicators who were perceived as less credible or expert were less likely to be seen by clients in a second interview… and less persuasive in presenting the results of psychological tests… and therapeutic interpretations…" (page 52-53)

This may be extremely frustrating to the therapist who becomes quickly invested in therapy with the prospective client. Client expectations for the therapist may be overtly presented. The client may request a therapist with specific experience or expertise in a treatment modality: individual versus couples, family, or group therapy; or with particular presenting issues: depression, substance abuse, etc. On the other hand, the request may be for particular therapist demographic characteristics such as for a male or female therapist, someone of a certain age, sexual orientation, religious background, and ethnicity or race. What characteristics are comforting, disconcerting, unfamiliar, or what and how intense the client transference may be cannot be determined until the therapeutic relationship is already in action. Some client requests may be relatively unimportant such as a slight but not compelling preference for a female therapist instead of a male therapist. Other requests or preferences may be intricately tied to the presenting issue- for example, being more comfortable with a female therapist because of safety fears from dealing with childhood molestation by a male relative, or wanting a male therapist to help deal with issues deriving from the client's distress from having an emotionally unavailable father. The potential client will pre-select or de-select a certain therapist because of any of these and other significant issues. The therapist never contacted would never know he or she was eliminated from consideration. While expertise and experience can be gained, the therapist cannot change many of his or her innate demographic characteristics, nor can the therapist address possible client prejudices or inhibitions that are never presented in therapy that does not ever begin. However, the therapist can attempt to productively address characteristics that determine likeability, trust, competence, and credibility, if they are identified. While the therapist cannot directly address the yet to be known client unarticulated expectations of the therapist presentation, he or she can consider various potentially relevant issues that affect pre-therapy and initial credibility.

THERAPIST "ATTRACTIVENESS"

The director of a community counseling agency declared an overt preference for employing "attractive" therapists. His definition of therapist "attractiveness" was not specifically based on physical attractiveness from social-cultural standards, but encompassed an overall positive emotional and psychological energy with an intellectual vitality. This energy expressed in a general social attractiveness to the client. He felt that negative emotional and psychological energy within a therapist would reveal themselves to the client in microfacial expressions, body posture, tonal cues, and other non-verbal communications. The client would not find such a negative therapist presentation as "attractive," especially when the client is dealing with his or her own psychic "unattractiveness." Several clients have told the therapist, that the friend, associate, or professional contact referring them for therapy had recommended various common positive characteristics such as being smart, real or genuine, "really good," but had emphasized the therapist's positive "energy." Discussions about the effectiveness of therapy and the therapeutic relationship the therapist conducts during the course of therapy and at the end of therapy have included similar feedback. This may be due in part to the activation of mirror neurons in the client triggered by the emotional energy and cues emanating from the positive upbeat therapist. In the first session or later during therapy, the therapist may also ask the client who he or she knows had a choice of prospective therapists to pick from, why he or she picked the therapist from among the others he or she had talked to on the telephone. Again, the feedback was similar referencing the therapist's energy and attitude. This was particularly interesting because at that point with only telephone contact, the client had yet to see the therapist in person to gauge any physical attractiveness, or to have been triggered by any visual cues.

The client may have some socially or culturally-derived spectrum of physical attractiveness, he or she is comfortable with. The therapist in his or her community can only make accommodations to a matching socially or culturally-derived spectrum of physical attractiveness as he or she feels appropriate. Depending on various social norms such as locale, agency, and age, the therapist has an implicit to explicit standards for appropriate personal and professional presentation. Clothing can be as informal as t-shirts, blue jeans, and open-toe sandals to professional casual attire or to business suits (and ties for men). Gass (1984, page 53) reported mixed findings about therapist attire. While some research found the formality of attire had no impact on client disclosure or ratings of the therapist's attractiveness, there were also some indications that moderately formal therapist attire was positively perceived by clients. Various factors may be relevant, such as the client's own style of dress being substantially more or less formal than the therapist's attire. For example, a client dressed in cut-off shorts and a t-shirt (a $10 ensemble) may feel over-whelmed by the therapist dressed in a three-piece pin-striped suit (a $3000 ensemble). Related to style of clothing would be class differences between the therapist and the client, which the shorts and t-shirt versus suit may symbolize. There is a general social standard of dress depending on types of professions from the high formality of many attorneys to formal standards of the business office versus service professionals. The "uniform" of some professionals are clearly identified, such as dress for police officers, doctors and other medical professionals. The client may perceive the therapist who wears very formal attire as pretentious. The therapist who is more client-centered or hold humanistic orientations may purposely choose clothing on the more casual part of the spectrum. The client may come to therapy with conscious or semi-conscious expectations of how the therapist should appear. On the other hand, the client may not have specific conscious expectations about therapist appearance or attire, but may quickly find a therapist not fitting into a previously unarticulated visual template. Depending on the situation and circumstances of the meeting room, building, and locale, the client may not anticipate a therapist dressed in a tank top, shorts, and flip flops... nor perhaps, a three-piece pinstriped suit. This would depend in large part upon the social and cultural expectations of client and what he or she is familiar with. For the client who is attending therapy for the first time, the therapist may be prudent to assume generic professional (possibly, casual professional) attire.

THE THERAPY NEST

Pressly & Heesacker (2001, page 149) discussed eight elements common architectural characteristics of space in the therapy office. They are (a) accessories, (b) color, (c) furniture and room design, (d) lighting, (e) smell, (f) sound, (g) texture, and (h) thermal conditions. These characteristics of space in the therapy setting can influence therapist credibility in the eyes of the new client. The therapist who shares an office would probably need to be more neutral in embedding his or her personality on the office. The therapist who sublets from another therapist will of necessity defer to ownership of the space or problems would arise. Personal and professional compatibility between the tenant or owner and the sub-leaser would hopefully result in office décor compatibility. The importance of the office décor may appeal to the client but almost certainly does something for the therapist and reflects the therapist in some manner. As the setting is more comfortable for the therapist, it tends to reflect his or her personality. It becomes the professional "nest" of the therapist. The therapist may spend anywhere from a few hours to 12-16 hours in his or her office… from a couple of days to the entire workweek. The therapist who is happy in his or her space is more likely to show positive attitudes and behaviors toward clients. This may include the positive energy that the client finds attractive. An unhappy or disaffected therapist is more likely to inadvertently convey their negativity to clients. Clinical interventions and judgments may be influenced because of this.

The therapist should use good judgment regarding office décor that might be offensive or emotionally triggering for clients. Clients may differ in their interpretations of artwork, perhaps finding some sexually suggestive and offensive. "Research supports the use of texturally complex pictures of natural, soothing environments rather than poster images. Research also suggests that plants may be particularly beneficial when working with certain client populations, such as terminally ill clients and aging clients, because they represent life, growth, and renewal" (Pressly & Heesacker, 2001, page 150). There are variations in preferences for color by age, gender, and culture. In general, neutral room colors offer flexibility and are practical for shared office space. Darker colors can make an overly large office more intimate, while white and other light colors can make a small office seem larger (Pressly & Heesacker, 2001, page 151). The client tends to prefer intermediate sitting distances in the therapy office. Female therapists are seen as more competent in traditional offices, while male counselors seen as more competent in humanistic or more casual offices. Offices with reduced privacy often decreased self-disclosure, while warm intimate offices promoted greater self-disclosure. Clean offices with living elements and accessories increased comfort as opposed to cluttered offices. Initial credibility is aided by displaying diplomas and awards, when there are other credible enhancing behaviors as cues. The client may feel more comfort, autonomy, and equality if he or she has control over moving furniture to adjust distance between the therapist and himself or herself. This may be relevant to client's social comfort and cultural norms. Moveable furniture or multiple seating options can also show dynamics among families, couples, and the client-therapist dyad. A client may move his or her chair closer to the therapist as he or she becomes more comfortable. The therapy office that must meet requirements for a health care or medical care facility must also be in compliance with the American Disabilities Act for accessibility for individuals with physically disabling conditions (page 153). Pressley & Heesacker also cite research used in combination: soft lighting, full-spectrum lighting, and natural lighting "may facilitate greater self-disclosure, reduce the risk of depression, and be perceived by counselors and clients as more desirable" (page 154).

The therapist should also be aware of unpleasant smells, smells that may trigger memories, that food or fruit smells may decrease clients' depressive moods, and the potential detrimental effects of bad breath, noxious smells, and intense smells, such as heavy perfume and cologne, may have on the therapeutic process and relationship. "Unpleasant smells may have a pervasive, and perhaps even unconscious, impact on the evaluations that clients and counselors make of one another" (page 154-55). Sound issues should also be considered, especially sounds that may be undesirable or too intense. Clients are reassured with water sounds and music used to block external sounds and to keep therapy work confidential. "Furthermore, research indicates that slow, quiet music may be used to calm agitated clients and decrease stress" (page 155). Texture can be influential to client's comfort. Soft textures convey intimacy and give dimension to a space. Heavy textures make small confined space feel even smaller and confining. Soft textured surfaces absorb sound and to increases the sense of privacy, while bare, painted concrete block walls echo. Flat or satin paint will soften the environment by decreasing glare and brightness (page 156). Room temperature also influences the comfort and mental concentration of both therapists and clients. Therapist who are sensitive to temperature comfort differences can adjust the thermostat, or provide sweaters, blankets, or fans, as needed (page 156).

Gass (1984, page 53) noted that recommendations about seating arrangements in therapy were largely intuitively based. A desk between the therapist and clients decreased the anxiety level in a significant number of patients and lowered the interviewer's credibility rating among high anxiety clients. He hypothesized that this suggested "a possible correlation between client anxiety and a desire for greater proximity in the seating arrangement." He also reported research that women seem to be comfortable with smaller personal space zones than men, and that heterosexual pairs have smaller zones than same-sex couples. There may be considerations about seating and personal space depending on the match or mismatch of gender between the therapist and of the client. Brischetto & Merluzzi (1981, page 82-83) found that research overall did not find clear associations between therapist gender on client's perceptions, while finding that with same sex and opposite sex therapist client pairs, same sex pairs were associated with greater degrees of empathy. However, hypothetical female therapists who occupied a professionally decorated office were considered more credible than those who occupied a more casually decorated office. The opposite was found for male therapists. Male therapists in casually decorated offices were perceived as more credible than those in professional offices. And there may be other differences depending on class, race, age, culture, and history of trauma and so forth, some of which may come from unconscious to conscious social prejudices. How may the gender of the therapist influence couple therapy with heterosexual couples? With homosexual couples are there additional influences depending on the gender and/or sexual orientation of the therapist? Isolating variables, however, for potentially distinctive influences may not be useful or appropriate in complex clinical situations. Gass makes this point when he refers to "casual" and "humanistic" versus more formal office settings. "…the meaning of individual cues for a client may be determined only within a more global context that consists of numerous cues. When dressed in casual attire, for example, the therapist was perceived as more personally attractive only when he was seated face-to-face with the client. This general preference for a casual therapy context… observers to be impressed most favorably by a male therapist when he was imagined in a casual, "humanistic'' office setting rather than in one with more traditional decor. Female therapists, however, were found to convey maximally favorable impressions in a formal office context" (page 55-56).

The overall gestalt of the therapist and office combination is made up of many cues that the client may tune into. Some may be subtle and draw attention and imply meaning for only a particular client or two, which may leave the therapist unaware of any need to address them. On the other hand, other cues may be more obvious, and can and should be addressed by the therapist. A therapist who had twisted his back was told to do exercises to build up his abdominal muscles and lower back including using an exercise ball. The instructions for the ball, in addition to several recommended exercises said that sitting and balancing on the unstable exercise ball would cause him to work out the abdominal muscles and lower back unconsciously. It became his regular "chair" in his therapy office that the therapist would have to make a point of explaining to any new client. Perched on top of a big black (then gray) rubber ball did not make for an expected professional presentation to an already anxious new client! This was the therapist who was going to help!? The new client tended to take the therapist's quick one-minute explanation in stride. The therapist can have backaches too… how human! As with most therapist-client interactions, the need to explain this became an opportunity to build credibility and rapport with the client.

With awareness of various recommendations, the therapist should otherwise decorate the office with whatever is personally and professionally attractive or meaningful. One therapist's office walls are covered with an over-abundance of pictures, art, and objects. Although, it clearly is a professional office, it is not a particularly sterile or neutral office. Things literally hung from the ceiling. This therapist's clients often commented on how they liked the office. This may not be because of any inherent esthetic beauty, but because the office reflects that therapist's personal and professional personality, which may be the "energy" clients had already matched themselves to. Clients often said that the office "fit" this therapist. The office décor also more directly served the therapist therapeutically. This therapist often used metaphors in therapy. On the office walls are all kinds of pictures or art that can become a part of the therapy at any given time.

Directly behind the therapist's seat in the line of sight was a tapestry of Alice falling down the rabbit hole from the story "Alice in Wonderland" by Lewis Carroll. One of the therapist's favorite metaphors is evoked when a client talks about doing something stupid again, or being drawn once more into some crazy family or work dynamics to his or her detriment. The therapist can fed back, "It's like you're Alice falling down the rabbit hole. All of a sudden, everything is crazy! A white rabbit is talking to you… it has a watch. There's a caterpillar smoking a hookah. There you are at the Mad Hatter's tea party celebrating everyone's unbirthday! Did you know you were falling down the rabbit hole?" The client often says that he or she knows the rabbit hole is there- the familiar dynamic or temptation looms… and how he or she seems to fall into it anyway. Therapy processes the old dynamics and its cost. Then, the therapist can ask, "Do you know what happens at the end of 'Alice in Wonderland?' Alice has angered the Red Queen of hearts, and she's directed her card-soldiers to cut off Alice's head, "Off with her head!" Alice is terrified… but then she has a profound realization. 'You're nothing but a pack of cards!' All of a sudden, the cards are blown away, and Alice finds herself back in the real world. Essentially, Alice is saying as you can say when you've fallen down your own rabbit hole, 'Hey, wait a second! It's all bull!' How can you stay in the here and now as a powerful, self-determining, and competent adult, who can choose your own life?" More therapy ensues from this intervention. Quite often, once this metaphor has been introduced a client will come in and immediately point to the tapestry of Alice and announce, "I fell into the rabbit hole again!" or "I started to fall into the rabbit hole last week with my ex, but I caught myself!"

The office also had a "Cat in the Hat" poster with the Cat balancing innumerable household items including a rake, a cake, and the goldfish in its bowl. Metaphors about balance are at the ready. Calligraphy of the Chinese word for "learning" which is made up of the characters "study" and "practice" hangs to the right of the therapist. "How do we stop fighting so much?" is but one client question that draws the "learning" calligraphy into therapy. Couple therapy is "study" but it'll take "practice" at home to learn how to be a healthy couple. The client who wishes everything would just be fine gets shown the plastic toy pony because "If wishes came true, then everyone would have a pony. You however will have to work on life." A cheap plastic trophy gets put up for "awarding" to one partner of a couple when they start the "Who-is-the-Most-Aggrieved Contest," and the couple is challenged, "So what do you really win if you're the biggest victim in this relationship?" Plastic eyeballs come quickly out of the desk and rolled across the floor, when the therapist catches someone rolling his or her eyes at the partner! Other things lie about because of the therapist's extensive experiences. They can be in child development, as discarded treasures from a spouse's Kindergarten classroom, old toys of now adult children, and because the therapist likes toys!

The casualness and eccentricity of this office reflect the therapist's personality. Any object or art may become activated as symbolic or a metaphor in therapy- some over and over, and some yet to be discovered. The joy and excitement of using "found" therapeutic interventions in the office can be a part of the energy that is the therapist's personal and professional persona that works for his or her clients. Some therapists often use humor to break the intensity of emotional reactivity- not to avoid addressing issues, but to gain some perspective so they can be addressed. Clinical judgment is critical to the décor and the use of metaphors and humor, as it is to any therapeutic strategy or tool. Despite flexibility and judicious application, for those clients who are strongly adverse to a particular personal and professional style and energy, it is reasonable to assume that they pre-select themselves not to be involved with a particular therapist for whom there is not a "fit." Over and over in many forms, therapists get confirmation that clients connected with professionals that are "real" or "genuine." Playful sarcasm and metaphors and over-decorated offices are not a recommendation for the therapist. Rather, each therapist should create his or her own clinical "nest" to fit the individual and therapist he or she is at the core.

COMPETENCE, KNOWLEDGE, & EXPERIENCE

A prospective client wants to know that his or her potential therapist is competent, knowledgeable, and experienced about the presenting issue (depression, anxiety, infidelity, academic problems, etc.) or the treatment modality: child, individual, couple, or family. The client finds him or herself immersed in a problem that is difficult to understand, much less resolve. Although, the client is intimately involved in the problem, such familiarity is not sufficient to keep him or her from staying stuck in the problem. The client looks to the therapist to be the expert in the problem, and give guidance to get him or her unstuck. Positive notoriety or professional status gives hope to the client and makes the client more willing to believe in and accept the therapist's assistance. "…expertness and status may increase the helper's ability to influence the client and, thus, promote greater client improvement… credentials, especially a lack of them, can affect clients' acceptance of therapists' influence… based upon a conceptualization of the helping relationship as an interpersonal influence process... In the attitude change model the manipulation of critical source characteristics such as credibility and attractiveness was associated with differential attitude change. For example, persuasive communications attributed to 'credible experts' would be associated with a greater degree of attitude change than the same message delivered by inexpert sources" (Brischetto & Merluzzi, 1981, page 82).

The therapist can demonstrate what he or she knows and does, and knows and does well. As relevant to the prospective client's presenting issue, the therapist can reveal his or her orientation, work style, philosophy and the reasons why they are appropriate for the presenting issues. The ability to identify and articulate the therapeutic process to the client creates greater credibility. When the client in fact experiences the therapist acting as he or she has indicated therapy would happen, the therapist's credibility further increases. Becker & Rosenfeld (1976) studied Albert Ellis who is renowned as a therapist and theorist to see how he practiced therapy. While their interest was to determine if Ellis practiced in therapy what he preached as a theorist, their study also illustrates the therapist stance of status and expertise. Ellis used a significant educational approach, often telling specifically which client beliefs were creating an emotional problem, and then logically challenging them. His therapeutic process asserts that the therapist's role and expertise is to identify problematic client beliefs that cause the client to make poor life decisions. By taking an authoritative stance, he tries to convince the client of the errors in the thinking process. Their study found that "Ellis spent the most time utilizing didactic teaching (…36%), he used rhetorical questions about three times as frequently as factual ones (…16% and …6%), he frequently used concrete examples as a teaching aid (…13%), often showed the client what specific beliefs the client held (…8%) and logically argued against irrational beliefs (…6%)" (page 874). He gave direct advice or alternative actions. Sometimes he directed the client's behavior in the therapeutic setting. He praised the typical client several times, and homework was assigned frequently. Ellis was active and directive, taking a teaching role. He was forceful with the client, attempting to change the philosophy of the client (page 875). Becker & Rosenfeld essentially found that Ellis did pretty much what he said he would do in therapy, based on what he said would be effective. His competent and knowledgeable logical presentation of problematic thinking, concrete examples, and consistent challenges come from his expert status. The client often prefers a therapist who confidently shows competence and knowledge about the client's issues and problems. Ellis as the therapist-teacher asserts a role that a willing client-student may require.

Sharpley & Heyne (1993) discusses with regard to therapist communicative control and client-perceived rapport, a difference that defines therapist-client conversations. They look at whether there is a shift or not in the therapeutic topic. Topic-Initiation communication shifts the topic from the current topic by initiating a new topic into the conversation. In contrast, Topic-Following communication does not shift the topic but continues the follow the current topic of conversation. The therapist may need to demonstrate communicative control quickly, based on their finding of low frequency of Topic-Initiation responses for low rapport rated minutes during the beginning of the initial session. In other words, allowing the client to continue the topic uninterrupted seems not to build rapport. When the therapist maintains control of therapy by using frequent Topic-Initiation responses, the client may see it as indicative of the therapist expertise. This may be experienced as an empathic therapist having something to add to the client's awareness. Instead of just following the conversation (not shifting the topic), the therapist's interrupts to inject something that he or she has become aware of from actively being involved in the client's experience. The therapist seems to understand the client and is able to deepen the client's understanding or insight to his or her problems. However, too frequent Topic-Initiation responses can also be experienced as the therapist disregarding the client's perspectives and not being present with the client. That leads to low perceived empathy. While frequent Topic-Initiation responses have a mixed association with high therapist rapport and effectiveness, high levels of non-controlling therapist responses such as Topic-Following were significantly associated with therapist ineffectiveness. It may be that primarily following the client's lead may leave the client feeling the therapist has little to offer in therapy.

Topic-Reintroduction responses, which also shift topic are a subset of Topic-Initiation responses. Instead of initiating a new topic, Topic-Reintroduction responses reintroduce client information that was previously discussed. The therapist brings up information previously presented in therapy for the client to discover new and important ways at seeing things. While the client may experience Topic-Initiation responses as relevant or seemingly irrelevant, responses that are Topic-Reintroduction are not only perceived as relevant, but as indicative of the therapist's insight and skill. It also demonstrates not only that the therapist has been listening to the client, but attending from deeper, wiser, and more expert perspectives. The following example of therapist reintroduction may show therapist expertise to a prospective client as it offers previously information for reconsideration in a revealing perspective. "You know how you're saying how you can't stand how your partner ignores you? That sounds a lot like when you told me how your mom favored your sister, and made you feel ignored. Do you feel like you're still fighting the same old battle?"

The therapist had listened when the client spoke of being ignored by the partner and had retained it for possible future relevance. As the therapeutic conversation continued within the same conversation, later in the session, or weeks or months later, something happens that cause the therapist to make a hypothetical connection with the original information. The therapist then offers the Topic-Reintroduction communication to the client for consideration. Reintroducing the information for comparison and consideration relative to more current experiences may facilitate new awareness or insight. Feedback may also be reassuring regarding therapist knowledge if it takes information and incorporates it logically into relevant psycho-education and a conceptual framework. When the client may be talking about being angry at or becoming resentful of the partner because of recent behaviors, the therapist can draw upon his or her expertise and experience to recognize and identify important dynamics. "Old resentments in old relationships often get mirrored in new resentments in new relationships. That's especially possible if your partner doesn't communicate upset well… perhaps, from family models of conflict avoidance."

This therapist feedback could be very powerful if the client finds the speculation about family models pertinent to his or her partner. When the client or the couple presents controlling behavior, the therapist can use a Topic-Initiation response to initiate a new topic for example, about any history of alcoholism and drug dependence that may prove very relevant to the client or couple's issues. "Is there any alcohol or drug problems in the family history?" This would show knowledge about and competence in recognizing characteristics about dysfunctional family systems. Prospective clients, as individuals, couples, or families often feel incompetent and ignorant about their own functioning, and seek a therapist who demonstrates competence and knowledge. Moreover, beyond academic knowledge or credentials, a prospective client also wants to know that the therapist is experienced working with and helping others with similar issues. For the two therapist response examples above, the therapist can add a story showing experience with the dynamics. The therapist can reflect on "a client who…" using non-revealing confidential information to tell success stories of similar clients, their problems, and how he or she dealt with them in the past. For example, someone who has couples conflicts arising out of the challenges of blending two families, would be interested to learn the therapist's experiences with couples issues and co-parenting challenges of blended families. Self-disclosure, which was discussed earlier to build rapport can also be activated to tell a personal story that illustrates experience with a particular dilemma, issue, or dynamic. When a client has depression or anxiety about not belonging or fitting in, personal disclosure may be a productive topic shift. "I was one of a few Chinese kids in an all-black elementary school. So, not fitting in still kinda bothers me! I had to learn how to be OK with being different… to learn to be OK with myself. It really started with…" Hearing about the therapist's personal experience may be very compelling for the client and his or her experience, especially if the therapist's experience has a "happily-ever-after" consequence.

INTEGRITY, HONESTY, & PROFESSIONALISM

A prospective client feels more connected to the therapist if he or she gains trust in the therapist's words and actions. He or she wants to be confident that the therapist will not try to make things sound good when they aren't. As discussed earlier, anything can prompt important therapeutic exchanges. Right next to one therapist's office door is a photo from the "Wizard of Oz" movie of Dorothy with the Scarecrow, the Tin Woodsman, and the Cowardly Lion at the gate of the Emerald City that the therapist had altered by inserting the therapist's face where the Gatekeeper/Wizard's face is supposed to be. When a client notices this and asks what's that about, the therapist gets to say, "There was no magic that the Wizard wielded, but somehow he helped get Dorothy home, the Scarecrow his brain, the Tin Woodsman his heart, and the Cowardly Lion his courage. I have no magic as a therapist, but therapy can find you the help you need. It's not going to help you, if I let you believe there's going to a magic wand to make everything OK. It's going to be hard work."

When the therapist can convey that he or she has the best interests of the individual, of the couple, or of the family at heart, the likelihood of an appointment scheduled or therapy beginning is increased. The therapist can tell a prospective client exactly that or find other ways to communicate integrity and honesty. In the initial telephone contact, a prospective client often asks how many sessions it will take. With the appropriate sensitivity and demeanor, the therapist may playfully but pointedly reply, "Well, it took you ten years to get to this point. I might be pretty good, but I'm not that good! It would be nice to tell you a few sessions will be enough. I know that's what you'd like to hear, but how long it takes will depend on what we discover it is all about." The therapist may go on to describe how and when therapy can be short-term versus when it may become long-term. Only when the therapist understands his or her therapeutic process and orientation can he or she articulate and assert the integrity of therapy to the client. The therapist can present examples of how previous clients have benefited and/or resolved concerns with a few sessions or with long-term involvement. Any therapist communication that explains the process of therapy can be helpful such as will be discussed in a later section on "No Process to Ownership of Process." Such open communication includes the prospective client in the therapeutic process, as opposed to the therapist acting as an omnipotent professional manipulating him or her. The communication implicitly asserts the client as being an intellectually, emotionally, and psychologically qualified partner in therapy. This reassures unspoken client anxiety about whether the therapist will treat him or her fairly and respectfully. The client as an individual, a couple, or a family often already holds significant anxiety about inherent worth and being negatively judged.

Establishing experiences of honesty and integrity and appropriate client-therapist roles are essential to successful therapy. Establishing them immediately in the initial contact or first session increases the likelihood of individuals committing to therapy. Unhealthy or dysfunctional relationships or life can be characterized as individual, couples, and families problems with boundaries: rigid boundaries, enmeshed boundaries, and inconsistent boundaries. The therapist may be aware of helping the client deal with his or her boundary issues in life and relationships, but may not be sufficiently attentive to how a client pattern of boundary issues may manifest within therapy. Professionalism is essentially about boundaries as well. Holding forth what is realistic or unrealistic in therapy is a professional response involving therapeutic process boundaries. A prospective client may ask for therapy or interventions that essentially involve boundaries. This may be asking the therapist to hold a secret from the other partner, to change schedules (including asking for appointments or contact availability outside of the therapist's normal schedule), personal questions, over-involvement or under-involvement, and so forth. While the therapist should be honest with the client (and self-disclosure can be therapeutically beneficial), honesty does not require full disclosure of personal information… or interactions outside of the client-therapist relationship. On the other hand, boundary issues can come up around fees, managed care regulations. The client may not be aware of how his or her behavior may be manifesting boundary issues, in particular his or her habitual boundary problems. The therapist may set a therapeutically relevant boundary during the initial phone conversation about managed care billing or availability as much as about a no secrets policy among partners and the therapist. Asserting and explaining the billing boundary or the no secrets boundary may reassure individuals and couples that the therapist may be the one who can help them with their boundary problems. The professional therapist offers and works within appropriate boundaries that the client may have had minimal prior experience with. The client may unconsciously be trying to draw the therapist into his or her dysfunctional boundary and role pattern with a request. Asserting clear and appropriate professional and therapeutic boundaries as early as the first contact may model the relationship boundaries that the client is intuitively seeking.

CLIENT PRESENTATION & THERAPIST RESPONSE

The therapist has somehow through some outreach, marketing, or networking gained sufficient credibility for the prospective client to make an initial contact by phone, e-mail, or mail. The therapist's initial credibility with a prospective client may be very substantial due to an enthusiastic referral from a former client of the therapist, another therapist or other professional, or other acquaintance of the therapist. The initial credibility however may be minimal or very tentative if the contact came from less personal reasons, such as

license or licensure status,years of experience,the therapist's office being close to the prospective client's house,the therapist having a surname that sounds like the same ethnicity of the client,the therapist being the first to return or happen to answer in person the client's phone call,the name of the therapist being at the top of a managed care provider list or being alphabetically listed first.

Or, a slightly more revealing mention in a newspaper or magazine article, a telephone book ad, newsprint ad, brochure, website, or other advertisement may cause a prospective client to hope the therapist may be a possible match for his or her needs. The therapist can immediately assess for his or her probable credibility in the eyes of the prospective client by asking how the client found the therapist. A highly positive referral from someone who knows the therapist well and whom the client respects affects initial credibility. However, Goldstein & Shipman (1961, page 133) found that the positive referral itself did not predict higher satisfaction with therapy outcomes. The therapist needs to build upon whatever credibility the client holds for him or her. The therapist should be very conscious of the tentative investment of a prospective client, especially that from a qualitatively lesser referral. A prospective client is more likely to commit to therapy if the therapist communicates and intervenes in ways to increase credibility. Initial impressions are but initial cues and the therapist should remember, that "therapist reputation and other initial impressions may affect the client's choice of a therapist, but that subsequent progress is likely to depend more on the quality of the therapeutic interaction than on aspects of the therapist's reputation" (Brischetto & Merluzzi, 1981, page 83). The initial choice to call one therapist versus another may be based on reputation, but subsequently clients need to have substantive experiences in the initial interactions on the phone to set an appointment, and additional substantive experiences in the first session to continue. While the therapist may take research into consideration when designing a brochure or business card, marketing, decorating his or her office and determining an appropriate personal professional dress code, "…the actual behaviors of the interviewer seem to render introductory status and sex differences unimportant in determining perceived expertness. However, because the social attraction dimension emerges as most salient, the degree of social or interpersonal attraction… may emerge as a more pertinent variable when in-vivo interviews are used to assess differences in the perception of males and females. Thus, reasonably competent behavior by male and female interviewers may eliminate preconceived or sex-typed perceptions with respect to expertness; while differential expertness is eliminated, social attraction emerges as the discriminating source characteristic. Thus, it might be inferred that relationship or interpersonal concerns are represented in that trend" (page 86).

Initial therapist credibility is put to a test when a prospective client presents his or her interpretation of what his or her, the couples, or the family's problems may be. The therapist may respond by asking simple but probing questions and make observations that demonstrate insight and awareness about the client. Psycho-educational feedback can help a prospective client understand himself or herself and the couple’s dynamics. This feedback during the initial phone conversation or first session (preferable during both interactions) can distinguish the therapist from other therapists. Credibility is increased if the therapist can give relevant and insightful interpretation based on what the client presents. "Interpretations are therapist propositions that go beyond what the client has overtly recognized, add qualitatively to client verbalizations, and present new meanings to clients… An important element of interpretations is that they offer explanations to clients…" (Gazzola et al, 2003, page 82). Credibility comes out of the therapist connecting with the client, while connection also comes out of the therapist gaining credibility with the client. Everything that helps the client connect with the therapist also builds the therapist's credibility: rapport, integrity and honesty, competence and knowledge, experience, availability, a personal relationship, professionalism, and confidence. Of utmost importance is whether the client feels the therapist response, including an interpretation is connected to his or her issues, problems, and emotional and psychological reality. All therapist characteristics that build the client-therapist relationship must be found in actual behaviors. The client presentation will draw a confirming credibility and connection building therapist reaction and response when the therapist can:

Reveal unspoken secretsIdentify puzzle piecesConnect the dotsGuess family of origin experiencesReveal feelings, thoughts, experiencesElicit and honor vulnerabilityChallenge sensitively and respectfullyReveal semi-conscious and unconscious goals- secret goals

Gazzola says that psychodynamic therapies use interpretations frequently. Humanistic psychotherapies such as client-centered therapy (CCT) focus more on creating a climate of safety for the client, who the therapist helps engage in a process of self-discovery. Therapist interpretations are seen as implying that the therapist is the expert rather than the client about his or her behaviors, thoughts, feelings and wishes. In Gestalt Therapy (GT), the therapist should describe what they perceive without interpreting it. This fosters increased client autonomy and allows the client to find his or her own meaning. On the other hand, Rational-Emotive Behaviour Therapy (REBT) asserts clients become disturbed by their belief systems rather than rather than by the actual circumstances, behaviors, or occurrences. The therapist uses reason to help clients recognize their illogical thinking. Interpretation becomes a core technique to challenge clients' irrational beliefs that make them catastrophize the meaning of events. Client catastrophizing creates an interpretation that any problem is a catastrophe, which then causes the emotional disruptions. The therapist offers an alternative interpretation. The theory works from the overt intention of getting clients to see problems from different perspectives. Interpretation can help expand awareness and lead to insight. Therapist interpretation may be important to the client because he or she may think that he or she is somehow weird or perhaps, morally reprehensible. The client or couple may believe that they are not normal and others are not like them- they fear they are uniquely disturbed. Therapist interpretations provide a rationale for the client may need to feel human again. "Clients generally consider interpretations to be helpful… clients identified interpretations as one… helpful therapist responses in interviews conducted by counselling trainees espousing different theoretical orientations, including CCT and REBT… clients consistently identified interpretations as helpful therapist techniques" (page 83)

Gazzola et al (page 88) found that despite theoretical differences regarding the appropriateness of therapist interpretations, statistically there was no difference in the frequency of interpretations in CCT, REBT, and GT. "Although therapist verbal response patterns differed across therapeutic modalities, interpretations were used with similar frequency and it was also similar to those reported in psychodynamic approaches." In client-centered therapy and Gestalt Therapy, interpretations tended to facilitate clients' moment-to-moment exploration of experiences. In client-centered therapy, the interpretations were expressed more in the tone of therapist musings for clients to consider. In Gestalt Therapy, therapist interpretations were presented more authoritatively and confrontationally and oriented to awareness of the here and now process. While sharing focus on the moment-to-moment process contrast in client-centered therapy, Gestalt Therapy was more direct and authoritative. Gestalt Therapy focused more on behaviors than the client-centered therapy's focus on emotional experiences. In REBT, interpretations served to explain reasons for negative feelings. Interpretations sought to educate clients how with their belief system, they make themselves feel negatively about themselves (page 89-90). Despite professed differences in the appropriateness of therapist interpretations, it appears that interpretations are a common and welcomed part of therapy. Since each type of therapy had different goals and use for interpretations that were consistent with respective theoretical principles, it may be true also that individual therapists have different goals and uses for interpretations based on individual theoretical orientations. It may also be true that a particular therapist may or may not be willing to utilize interpretations during the initial telephone contact or first session rather than holding them for later sessions.

ACTIVE EARLY THERAPY

The client, especially in the initial contact and first session looks to the therapist to provide something tangible or impactful. An active and engaged therapist in early therapy versus a passive therapist may be good therapy in this stage. The therapist can make a concerted effort to quickly and assertively engage with a prospective client both in the telephone contact and in the first session. Interpretations are often crucial to creating engagement. With this active therapist process, the client often comments that he or she (or as a couple or family) had gotten more in the first session than in months of therapy with a previous therapist. The client would complain about previous therapists who had given little or no feedback. A common comment was that the prior therapists were nice enough and were very supportive, but that they had not told the client anything that helped the client gain better insight or awareness or lead to behavior or life change. In the initial interview or inquiry process, innocuous open-ended questions often lead to responses that for an astute therapist that quickly point to potentially fruitful and charged trails to follow and hot and juicy areas to explore. The client or couple may often respond vaguely or tangentially, giving hints or cues of more substantial issues or concerns. It may because the client is not yet confident in the therapist's skills or sensitivity to reveal secrets or vulnerability, or because of not being cognizant of the importance of particular experiences, thoughts, feelings, or behaviors. When the therapist asks various follow-up questions that are based on initial client information, it can imply greater insight and knowledge on the part of the therapist. Actual interpretations may not be necessary. "What do you wan to address in therapy?" or some other generic opening question or greeting, "Hi, this is Ronald" is followed by the prospective client response "I (we) want to come for therapy." The following are examples of subsequent pointed therapist questions that can be appropriate at some point in the phone conversation or in the initial assessment during the first session. Each of them reveals therapist sophistication or insight about the client seeking couple therapy. Each also can elicit responses that can be followed up with more questions, feedback, or interpretations.

"Is couple therapy your idea, your partner's idea, or both of your ideas?"

This question indicates that the therapist is aware that there may be uneven willingness to come to couple therapy. If one partner initiated couple therapy with a reluctant partner, then a follow-up question can be asked about what the differing motivations may be about.

"Is this a new issue or an old issue that has intensified or gotten worse over time? Or, is it both?"

This indicates that the therapist knows that some couples have tolerated long-term grievances that have festered and grown finally to the point of being intolerable. And that on the other hand, other couples may have recent disruptions, or new circumstances, or traumas that have thrown them into pain. If the caller is inquiring for his or her child, the question indicates awareness that recent events may have triggered new problematic behavior, while other behaviors may have been going on for quite a long time before reaching some critical stage precipitating the need for therapy. Or, that there may be some combination of developmental or historical issues and intensification due to some recent stressor. "

Why are you coming for therapy now, instead of before, and instead of waiting?"

The question indicates that the therapist understands that an individual, couple, or family can hold pain for long periods until accumulated experiences and/or new circumstances finally cross individual, couple, or family's thresholds of tolerance. Also, that personal growth in one individual can lead to rejecting old dynamics of the couple or family that were previously acceptable, or good enough.

A prospective client may consciously expect the initial contact to be primarily about scheduling, phone numbers, and other practice information, while also instinctively wanting and needing to have the therapist's credibility confirmed and to get connected. Therapist feedback, observations, or interpretations can serve the prospective client's subconscious needs. Theoretical guidelines and personal style will determine the extent of such interventions in the phone conversation and first session. Potential therapist responses may appear to belong to subsequent parts of therapy rather than the beginning of therapy. However these interventions, intrinsic to therapy are also relevant to the beginning of therapy. It can be useful to consider that processes in each stage of therapy are replicated over and over in every stage of therapy. Building or enhancing or maintaining rapport occurs throughout therapy. Other processes that are emphasized in later stages of therapy are appropriate in the beginning of therapy to specifically build rapport as well. Ivey & Matthews (1984, page 237) present a five-stage structure for the interview:

1. Rapport and structuring. "Hello."

2. Gathering information, defining the problem, and identifying assets. "What's the problem?"

3. Determining outcomes. Where does the client want to go? "What do you want to have happen?"

4. Exploring alternatives and confronting client incongruities. "What are we going to do about it?"

5. Generalization and transfer of learning "Will you do it?"

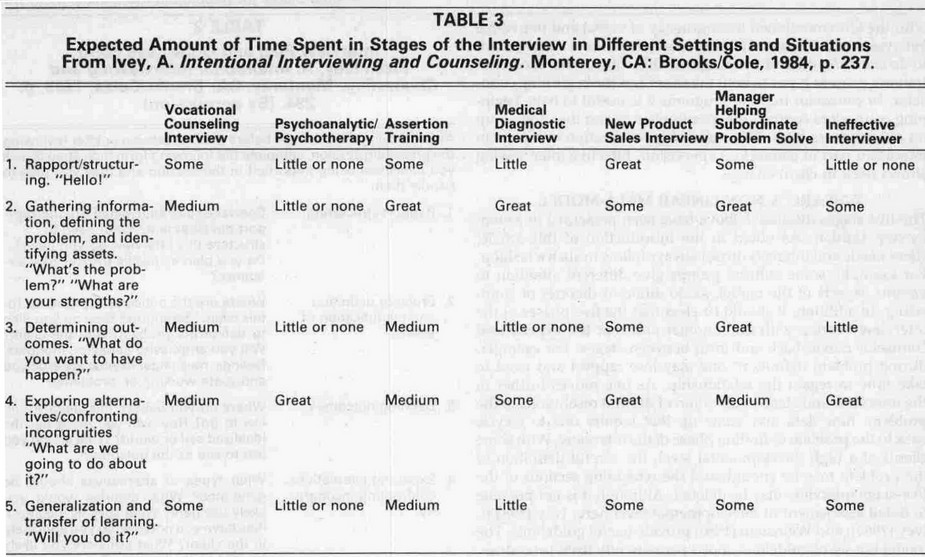

Although often listed as the first stage of therapy as Ivey & Matthews have done, rapport building is not a stage per se, but an ongoing goal and consequence of therapeutic activity. Building rapport is much more than an initial therapist presentation of being nice, wearing appropriate clothes, having a welcoming office, or being attentive with eye contact, nods, and open body language. In initial contact and the first session, beginning rapport is also developed through establishing therapist credibility. Credibility comes from the client experiencing therapist activity skillfully gathering information, determining outcomes, exploring alternatives and confronting client incongruities, and generalizing and transferring learning. Focused therapist attention or inattention and therapist behavior or misbehavior during early and later activities of particular information seeking, problem and asset identification, outcomes, and so forth continue to build or diminish credibility and rapport. Ivey and Matthews (1984, page 242, Table 3) present variations in the amount of time dedicated to their five stages of the interview for various orientations or types of interviews or interviewers: vocational counseling interview, psychoanalytic/psychotherapy, assertion training, medical diagnostic interview, new product sales interview, manager helping subordinate problem solve, and ineffective interviewer.

Of note, they assert that in psychoanalytic or psychotherapy interviews, the time spent in each stage is little or none except for a great amount of time in exploring alternatives. This could be interpreted as problem solving being prioritized over problem definition. In contrast, in the medical diagnostic interview and manager helping subordinates problem solve, great time is spent on gathering information, defining the problem, and identifying assets. Effective psychotherapy may be seen, especially for couple and family therapy to require the therapist to spend great energy and skills, if not also time in gathering information, accurately defining the problem, and sound diagnosis. This prioritizing would be more similar to the recommendation for a medical diagnostic interview. This implies less of an emphasis on a dogmatic theoretical orientation or therapy style that may or may not fit the client, but focusing on therapy as a modality that includes incredible diversity of presentations and issues. Clients who find themselves run through a set of interventions based on the therapist's favored theory or style of therapy may not find the work relevant to their issues. Solutions and interventions seem to be in search of clients, rather than clients in search of solutions and interventions. The therapist immediately loses credibility as someone who is not tuned into or even cares about the client's specific needs. On the other hand, the therapist sends a strong message when he or she actively gathers information and explores various definitions to determine a rational definition of the problem. This includes identifying client assets including prior attempts to solve the problems. The client, couple, or family feel respected as people with a unique set of dynamics who have experienced issues often shared with other human beings. A theory or group of theories are examined to see how they may be relevant and fit the client, rather than the client being force fit into a theory. Also of interest, is that Ivey & Matthews only see professionals in a new product sales interview spending a great amount of time in rapport building. "Selling" of the therapist and all relevant professional qualities and credentials to the client, as they meet the client's needs is critical to the client investing in therapy. Perhaps, the relationship of rapport to credibility would justify an emphasis on spending more energy and attention, if not time in this area. Treating rapport/credibility is not a stage but as an ongoing therapeutic need. Whereas, rapport may be defined primarily as emotional and/or social connection, credibility goes beyond emotional and/or social connection to also encompass confidence in the therapist's experience, intelligence, insight, and skills acquired in therapist-client interactions in therapy.

RESPONSES FOR BUILDING CREDIBILITY

The following are examples of therapist responses to client presentations that build therapist credibility. These are representative of types of connection building communications that create the therapist-client rapport that consolidates initial contacts and first sessions into invested therapy.

"You mentioned the financial stress from losing your job about 4 months ago. What does that mean to you? Not just financially, but about who and what you are as a partner, man, and provider? What does your wife think of… expect of you? How does it feel? What do you do about those feelings? Who are you, if you're not working?"

These questions are for gathering information, but are not completely open-ended questions. They are pointed questions that indicate that the therapist is aware of potential self-esteem and identity issues of a traditional male provider unable to work. The presentation of the couple may have been for conflict around parenting and household responsibilities. For this therapy, the therapist's revelation of the underlying loss of identity and its traumatic effect touches and honors the husband's vulnerability that he would not have presented on his own. Ivey & Matthews (1984, page 238) say that the function and purpose of the gathering information stage is "To find out why the client has come to the interview and how he or she views the problem. Skillful problem definition will help avoid aimless topic jumping and give the interview purpose and direction. Also to identify positive strengths of the client." Therapy in this situation has the potential to wander about aimlessly without addressing the core identity loss for the husband. The intervention of these questions acknowledges his sense of purpose to serve his family as a provider while also identifying its limitations.

"I see that you and your wife have communication problems. But it's not just that you two have communication problems, it's that you both have hurt from the communication problems. From what you've said, the hurt looks like it's been there for a long time."

This indicates that the therapist can go deeper than what the client presents. What is presented as a communication problem is redefined by the therapist as deeper wounding of the emotional bonds between the partners in the couple. Without the client presenting it as a goal or outcome, the therapist has compassionately spoken to the deeper and more critical goal of healing for the couple. Ivey& Matthews (page 238) say that the function and purpose of the determining outcomes stage is "To find out the ideal world of the client. How would the client like to be? How would things be if the problem was solved? This stage is important in that it enables the interviewer to know what the client wants. The desired direction of the client and counselor should be reasonably harmonious." While the client or couples presentation is of improving communication problems, the desired deeper outcome- often unspoken is healing of long-term injuries and a return to a joyous relationship free of pain. In this situation, the therapist reveals that he or she is in sync with the goals of the couple, even though the couple has not articulated them.

"Sounds like your husband is afraid that going to therapy makes him look like a bad guy. Maybe he thinks going to couple therapy is admitting that he's a failure… a screw-up. It'll be hard for him to get here, be here, and stay here."

This indicates that the therapist is aware of the client's struggle to get her husband into therapy. The problem of getting him involved and invested in couple therapy is defined as the first problem to address. Ivey & Matthews (page 238) say that the function and purpose of the gathering information stage includes "To find out… how he or she views the problem. Skillful problem definition will help avoid aimless topic jumping and give the interview purpose and direction." Failure to address the husband's resistance and proceeding as if he were fully invested would corrupt the therapeutic process. The problem of his reluctance can be defined as emblematic of problems in the couple’s relationship. While showing compassion for the husband's anxiety, the therapist's speculation about the husband also creates an alliance between the therapist and the wife. They have joined in the challenge of getting her husband involved in, invested in, and committed to couple therapy. The therapist can follow-up with additional information about how she will support the husband in the therapy. Later, the therapist can use this insight to show empathy and form an alliance with the husband as well.

"It's not just getting past the hurt of the affair. It's also both of you understanding… seeing what the affair was all about. Only then can both of you even hope to problem-solve why it happened in the first place. Otherwise, you'll never feel ok… you'll never will be confident that your partner won't do it again… and you won't be able to heal."

In the gathering information stage, this feedback indicates that the therapist is knowledgeable about the complexity of recovering from an affair. The psycho-educational description of the process and of how critical the requirement for understanding is, articulates for the clients both their feelings and a definition of the problem they often have not yet been able to conceptualize or verbalize. The outcome or goal of therapy has been redefined from only getting past the affair to gaining understanding and healing. The affair is no longer only viewed as the problem, but also as the expression of deeper and older problems in individuals and the couple. The client or couple is often excited as they recognize the truth; and calmed simultaneously that the therapist named it.

“You said you can’t please her. No matter what you do, you just don't see anything working. So, why do you still try to please her? That must feel awful. What about accepting she cannot be pleased? How about pleasing yourself?"

The individual (alone or in a couple or family) presents his or her stuckness and implicitly prompts the therapist to provide an alternative. Ivey & Matthews (page 238) say that the function and purpose of the exploring alternatives and confronting client incongruities stage is "To work toward resolution of the client's issue. This may involve the creative problem-solving model of generating alternatives (to remove stuckness) and deciding among those alternatives. It may also involve lengthy exploration of personal dynamics." This type of response can be appropriate when logical alternatives are unavailable or are consistently shot down by the client. It indicates that the therapist is aware of client, couple, or family's values and rules or personal dynamics that bind the individuals or members to dysfunctional unproductive behavior, despite the availability of logical alternatives. It prompts not an alternative solution that will not be accepted, but realization that unidentified and unchallenged values or rules are limiting choices and behaviors. The client or couple reveal their binding perspectives and discover alternative perspectives that may free them from stuckness. Bergantino (1997, page 383) refer to this as "an example of 'invading the unconscious' of the family in a way that has the possibility of creating an 'existential shift' (existential shift = moving all or most of the family members in a way that frees them from the psychic bondage" of some dysfunctional game or family dynamic. In this situation, the game is of being required to and persisting at trying to please the unpleasable partner, only to fail. Failing then gives the partner some psychic benefit despite cost to both partners.

"It sounds like both of you already know what you're doing wrong and what you should do instead. You don't need therapy or me to tell you that. You saw the problems long ago and you could feel you were doing it wrong back then."

This response acknowledges the frustration of the individual, couple, or family that they continue to behave poorly despite more than sufficient insight. Ivey & Matthews (page 238) say that the generalization and transfer of learning stage is "To enable changes in thoughts, feelings, and behaviors in the client's daily life. Many clients go through an interview and then do nothing to change their behavior, remaining in the same world they came from." The therapist response indicates that actualizing learning into concrete behavior can be difficult and offers therapy as a means to experiment and explore ways to activate their knowledge in life. In addition, the therapist demonstrates therapeutic sophistication by implicitly or overtly anticipating potential failure of behavioral implementation based on from prior failures by the client. This can give clients greater confidence in the therapist, who has shown an ability to resist simplistic solutions. The therapist presents as prepared to process more complex issues that have blocked the simple solutions.

While interpretations and feedback may address the underlying logic of client perceptions and experiences, therapist communication is most credible when it also speaks to the affective experience of clients. Language that has a sensorial quality in addition to an intellectual component may be the most effective, Ivey & Matthews (1984, page 239) discuss verbally matching client's model of "their world by using key words, phrases, and the significant constructs employed by the client… it may be helpful to match visual, auditory, or kinesthetic predicates when the client uses such words (e.g., visual predicates: 'I don't have a clear picture of what your are trying to show me.'). The intensity of rapport can increase with many clients if all three of the client's main sensory systems (visual, kinesthetic, auditory) are used (e.g. "I get the picture, you feel…, and it sounds like…" Clients and couple's lives and problems are more than dynamics, behaviors, and constructs. They are profound visceral experiences. When the therapist uses sensory language in giving interpretations or feedback, the message to the client is that his or her or the couple's experience resonates viscerally with the therapist as well. The art of the therapeutic process contains boundaries, strategies, principles, client variability, and therapist's skills, insight, and sensitivity. Rigid boundaries of time, structured scripts of what to say, and various do's and do not's does not preclude the requirement for therapist's use of self, sensitivity, experience, and most of all, judgment in the moment… at any moment of therapy. The therapist's initial phone conversations with prospective clients can go beyond time required for the logistic of setting an appointment to run from fifteen to twenty minutes. First contact interaction run as long as half or three-quarters of an hour. Some therapists or theorists think this would be excessively long and moves into "doing therapy." With the consciousness of creating credibility and making connection and rapport through identifiable processes, aside from strictly functional obstacles (inflexible need to use managed care coverage, schedule incompatibility, or financial inability), the therapist may find more rare when a prospectively client does not make an appointment for therapy. In addition, more rarely might he or she fail to show up. And rarely does the prospective client not become a committed client.