8. Confrontation & Conflict - RonaldMah

Ronald Mah, M.A., Ph.D.

Licensed Marriage & Family Therapist,

Consultant/Trainer/Author

Main menu:

8. Confrontation & Conflict

Therapist Resources > Therapy Books > Mirror Mirror- Self-Esteem Relationships

Mirror Mirror… Reflections of Self-Esteem in Relationships and Therapy

Chapter 8: CONFRONTATION & CONFLICT

by Ronald Mah

The therapist wants to promote healthy confrontation and to expose covert confrontation to bring them into conscious discussion. The individual, one or more partners or family members may have significant aversion to confrontation, which is an important form of mirroring. Confrontation reflects back the other person's experience, thoughts, and feelings about what the individual says or does or has said or done. Avoidance of confronting hurts, slights, and concerns because of fear of emotionally destructive conflict often highly contributes to relationship deterioration. Previous childhood or other life experiences including earlier relationship interactions with confrontation lead to emotionally destructive conflict. Heene et al. (2005) reported that depressed women had more demand-withdrawal and avoidant communication patterns. Both these patterns are characteristic of confrontation avoidance and are related to poorer marital satisfaction. It is not clear if depression causes these communication patterns or the converse is true that these poor communication patterns cause depression. On the other hand, Heene found that "self-reported constructive communication was a significant mediator of men's levels of depressive symptoms and marital adjustment. In other words, depressed men tend to report lower levels of constructive communication, which might lead to lower levels of marital adjustment. Conversely, lower levels of constructive communication in distressed relationships might be associated with depressive symptoms for men" (page 429). Constructive communication may be considered essential to or largely constitute effective and appropriate confrontation.

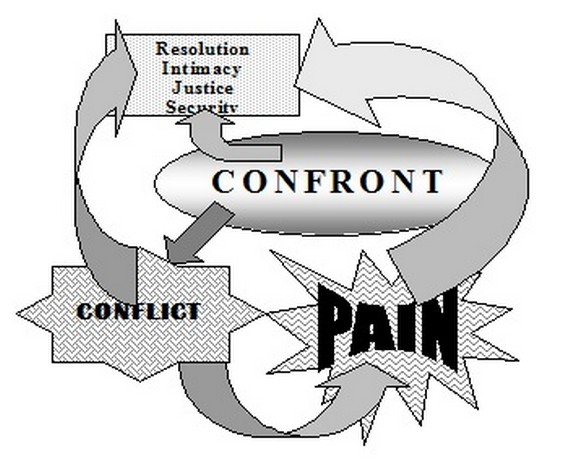

Effective and appropriate confrontation, however does not guarantee that there will not be conflict. Conflict may be welcomed by some confident individuals, but more likely to be viewed cautiously or fearfully. Heitler in an interview (Wyatt, 2009) differentiates conflict at two levels. "…conflict can be at a shared decision making or conflict resolution level. Shared decision making is what we call the process if it's going smoothly. We call it conflict resolution if the couple is getting oppositional. In this case, they were going beyond oppositional to desperate because they each felt so strongly wedded to their own concerns and unable to embrace it in a broader way to take into account the concerns of their partner." For some individuals the inability to take the other into account causes conflict to be experienced as causing intolerable pain. As a result, they feel the entire cycle of

confrontation -- conflict -- pain

They feel confrontation, conflict, and pain must be avoided. Unfortunately, that may mean avoiding the processes that lead to resolution, intimacy, justice, and security. Sometimes, confrontation, "I don't like that" leads to resolution, intimacy, justice, and security. The discomfort, sense of inequity, or displeasure is communicated and the other person may be responsive. Confrontation leads to people in a relationship working out a problem. Sometimes confrontation does lead to conflict- the individuals in the relationship argues or fights. However out of the acrimony can come resolution, intimacy, justice, and security. Grievances, balance, rights, privilege, and rights are disputed, negotiated, and the participants settle an issue. And inevitably, there are relationship conflicts that can be extremely painful. However, because of painful process there arise the outcomes of resolution, intimacy, justice, and security in the relationship. Poor or insensitive communication, old vulnerabilities, and hurtful messages stir up feelings and reactions that can prompt individuals to take mutual responsibility for reciprocal emotional needs. The therapist promotes, teaches, and holds individuals to the four communication/relationship rules:

1. Confrontation can lead to resolution, intimacy, justice, and security2. Confrontation can lead to conflict which can lead to resolution, intimacy, justice, and security3. Confrontation can lead to conflict which can lead to pain which can lead to resolution, intimacy, justice, and security4. No confrontation can lead to no conflict which can lead to no pain which can lead to no resolution, intimacy, justice, and security

The therapist is challenged to facilitate the therapeutic process and personal and relationship growth so confrontation becomes habitual, kind, and respectful. Therapy seeks conflict that is impassioned without abuse or shaming. The therapist must teach "fair fighting" so that individuals can gain confidence that intense emotion will not get out of control. Finally, the therapist must create and manage the therapeutic container so conflict, old grievances, and intense emotions lead to healthy progress. The individual, couple, or family need to experience that under the therapist's guidance that the pain can be tolerable and lead to growth, rather than merely repetitively excruciating. The individual, couple, or family needs to establish a working system of open communication. "When a family or system is in healthy balance every person contributes and his or her contribution is considered. No one gives more than they receive. Open dialogue between members is encouraged and valued and is not dependent upon age, gender, or status within the family or system. Negative behaviors are talked about in a way that does not lower a person's self-esteem or belief in themselves (Satir et al., 1991). They continue to see and understand each other as valuable even when experiencing conflict within the system. Conflict, in a healthy system, is an opportunity to explore and move to a deeper level. It can be a symbol of what is going on in the system without blame or judgment of the person" (Sayles, 2002, page 101).

The goal of therapy is for the partners or family members to have "good" fights in session, and eventually be able to have "good" fights at home. For the person in individual therapy, similar but also additional and different processes also seek him or her to be able to have "good" fights with the important people in his or her life. Productive confrontation, conflict with respect and sensitivity, and tolerable growth pain lead to resolution, intimacy, justice, and security in the relationship. The relationship goes to a greater depth when it can confront any issue with confidence and skills. These therapeutic and relationship premises may be difficult for some individuals to accept. Family-of-origin traditions or cultural patterns may make accepting confrontation difficult. For example, Moghadam et al. (2009) addressed Iranian and Islamic traditions regarding equality, fairness, peace, and harmony for a couple. "Equality is understood within the larger value of creating relational peace. Partners explain that it is difficult to maintain a harmonious relationship if they do not have equality, or a sense that each person is treated fairly. For example, when asked if equality was important in their relationship, a husband responds, 'to have harmony and peace means to be fair.' Participants view fairness or justice as an essential tenet of Islam that promotes relationship stability. Similarly, when asked what it takes to create equality in their relationship, a wife says that she must experience inner peace, 'when I am pleased from inside with my choices, peace is created . . . that means equal rights.' Thus, for peace to prevail, each partner must be content. An important question is what partners do if they do not feel content. According to Arezu, a young wife, keeping the peace means she must express herself, 'to be so comfortable that I can be myself and say what ever I feel like saying.'" This appears to coincide with a therapeutic and relationship model encouraging open expression of any potential issues that curtail contentment. Confrontation would seem to be acceptable.

The larger social-cultural framework is more complex, and apparently contradictory. "However, cultural ideals may also discourage women from expressing themselves. Although both men and women believe in peace as their ideal, in many families women are viewed as the keepers of the peace and the experts at it. The burden for keeping things smooth rests on them. According to Arezu, peace is maintained through women's sacrifice, 'men's needs are met all the time . . . she is here to live and sacrifice.' Women may or may not consider this fair, because what is viewed as fair is dependent on the social context and changes over time (Falicov, 1995; Knudson-Martin & Mahoney, 1996)" (Moghadam et al. 2009, page 45-46). Traditional female gender roles in American society remain influential. They would hold women as having greater responsibility for maintaining the couple's relationship. Gender differences may manifest in close heterosexual relationships in different problems faced by males and females. This may "in turn engender sex differences in conflict communication, attributional activity, and attachment styles" (Heene et al., 2005, page 432). Or, conflict communication, attributional activity, and attachment styles gender differences may cause different problems in males and females, including how they are experienced. The therapist should not assume that an apparently mainstream couple does not require cross-cultural approaches for embracing confrontation and conflict as means to relationship integrity. These unaddressed issues may have been key problems that lead to Terry and Bert eventually breaking up. And may remain important to the new conflicts and relationship problems. The therapist may need to explore how gender socialization may have complicated their communications and intimacy previously to uncover how it may still impact them. This may be an applicable exploration in both heterosexual and homosexual relationships. Same sex relationships are formed primarily with partners who grew up with heteronormative standards in families and in the community. They would have formed their own gender self expectations somehow integrating their same sex attractions.