20. Second Order Change - RonaldMah

Ronald Mah, M.A., Ph.D.

Licensed Marriage & Family Therapist,

Consultant/Trainer/Author

Main menu:

20. Second Order Change

Therapist Resources > Therapy Books > Out Monkey Trap- Breaking Cycles Rel

Out of the Monkey Trap, Breaking Negative Cycles for Relationships and Therapy

Chapter 20: SECOND ORDER CHANGE

by Ronald Mah

A very important concept of strategic theory is second order change. First order change is change that is considered within the values, rules, or expectations that are currently or traditionally held. First-order change according to "Watzlawick, Weakland, & Fisch (1974) …involves a variation that occurs within a given system which itself remains unchanged." Second-order change, on the other hand, "…involves a variation whose occurrence changes the system itself… it is change of change… it is always in the nature of a discontinuity or logical jump" (Levy, 1986, page 9). First order change involves small improvements and adjustments that do not alter the fundamental core of system, while second order change alters the fundamental structure. These adaptations happen within the course of the system's natural growth and development. A first order change may be an adjustment that allows the core patterns and process to stay the same. "The concept of 'order through fluctuation' and the theory of dissipative structures (Prigogine, 1984) suggested that fluctuations are a major vehicle for maintaining order and creating higher level order. The concept of 'autopoietic system,' which refers to a system capable of both creating and sustaining itself, deepens our understanding of self-organizing systems capable of self-transcendence (Jantsch, 1980)" (Levy, 1986, page 10). First order change is "change without change." Clients often look for a change that essentially is a variation of behavior that has already been proven to be ineffective. The early assessment process of therapy usually reveals the principles of the first order operating for the individual, couple, or family.

Selkie held the principle that expressing discomfort to Coleman will cause him to recognize the discomfort as an important signal. Coleman was supposed to know from the signal that Selkie wanted him to do something about her discomfort. Commiserate with her, pat her hand, or maybe reassure her. Selkie expected that partners in a couple have the ability to readily recognize discomfort expressed as a request for a response. This was obvious to her because that is what people in love do. Coleman for various reasons did not get it and as a result, did not give Selkie the response she wanted. Selkie kept putting out her signals over and over. Selkie continued to hold the principle and expect what she thought was the appropriate response without even being really aware of it. As a result, she reapplied the principle by continuing to express discomfort to Coleman. Selkie like most people who are frustrated trying something, tried the same thing again but more intensely. Coleman thought Selkie was awfully moody. So when she complained repeatedly and more intensely, he figured she was just being more moody. He did not get why she was getting so mad… and mad at him. He tried to avoid her since he did not know what to do. Selkie continued to complain how she was tired, worried, getting stressed, and so on. Her expectations keep her trying a new way to do the same thing! She wanted the therapist to suggest some behavior or words to make Coleman do what she had been failing to make him do.

Doing the same things but in a new combination or in a changed order often keeps everything in first order change. The therapist hears more of their stories. They have tried a lot of responses in the first order. Selkie had persisted in expressing discomfort but attempted different ways to do so. She tried to be more demonstrative or more restrained, stomp around the house first versus after verbally complaining, or start with expressing anger at Coleman instead of showing discomfort first. Coleman had continued to think Selkie was moody. He attributed it at various times to premenstrual syndrome, or work stress, or her phone calls with her mom. He continued to avoid her- trying to avoid her when she is upset, or anticipate her getting stressed and getting out of the way, or staying late at work, or drinking. As the couple tried change without change, the partners created and sustained the dysfunction that brought them to therapy in the first place.

"Drawing on fundamental concepts in the field of mathematical logic, Watzlawick et al. (1974) based their distinction between first- and second-order change on

(a) the logical relations among elements (members) and wholes (group) and(b) the types of changes that may occur among the elements given certain mathematical rules of operation.

By way of simple illustration, if a numerical group is composed of numbers whose mathematical rule of operation is addition, members of the group may be combined in various ways without changing the definition of the group, for example, (5 + 2) + 1 = 8; 2 + (5 + 1) = 8. Watzlawick et al. contended this state of affairs, even in its rudimentary mathematical form, depicts ways in which a myriad of changes in the internal state of a group (that is, changes among its members) make no difference in its definition as a group. This type of change maintains the coherence of a system and is referred to as first-order change. If the rule of operation is changed from addition to multiplication, however, a different outcome results, for example, (5 x 2) x 1 = 10. This type of change represents a discontinuity, jump, or transformation in the definition of the group and is what Watzlawick et al. called second-order change. Although first-order changes may still occur, for example (5 x 2) x 1 = 10; 2 x (5 x 1) = 10, they now function under a new rule structure" (Lyddon, 1990, page 122-23).

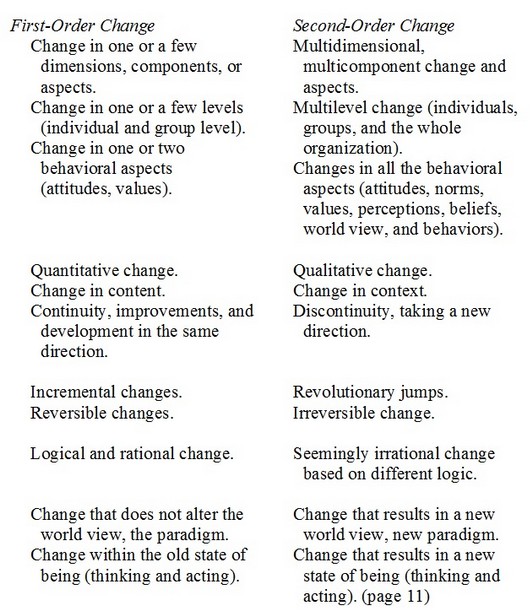

The following is a chart of the characteristics of first and second order change in organizations. An organization is a system as an individual intrapsychically, a couple, or family is a system as well. The principles Levy (1986) present are relevant to individuals, couples, and families.

A complex system such as an individual, couple, or family remains consistent through first order change, but can undergo qualitative change in the core rules and values governing their structure or internal order. People normally perceive and interpret interactions and behaviors in the first order as they seek to sustain what they are used to. When something occurs that requires a solution, their choice of solutions is confined to options defined by unconsciously and consciously internalized standards. These values, rules, or expectations would come from experiences and modeling in the family-of-origin and culture. "We use the term 'survival positions' to refer to a set of beliefs and strategies that individuals adopt to protect and manage their vulnerabilities. These positions are usually the best way a person found in the past to protect self or others in the family of origin, and to maintain a sense of integrity and control in emotionally difficult situations. Survival positions are often adopted before they can be put into words, and certainly before they can be evaluated critically. Survival positions include beliefs and premises that become 'mottos' to live by (Papp, 1983; Papp & Imber-Black, 1996; Zimmerman & Dickerson, 1993). Some examples of survival beliefs are: 'It's dangerous to be angry'; 'You can only depend on yourself'; 'Always please people'; 'Don't trust women'; 'Be weak and one-down'; 'Always be strong and don't show your vulnerability'; and 'If you get too close you will get hurt.' These beliefs are influenced by gender training, cultural norms, and family history. Survival strategies based on these premises are the actions that persons take to protect themselves. Other authors have described similar ideas in terms of 'strategies of survival' (Miller & Stiver, 1995), 'habits' (Zimmerman & Dickerson, 1993), and 'coping mechanisms'… Survival positions, so helpful and necessary in childhood, become part of the repertoire or dowry that individuals bring into their adult relationships. Survival positions can evolve and become flexible and adaptive, helping the individual deal with stress or adversity. Or they can become frozen in the form adopted in childhood, stultified and inflexible, so that when they are applied to the couple's present situation, they become a hindrance and a major element in perpetuating the couple's current relational impasse (Christensen & Jacobson, 2000)" (Scheinkman and Fishbane, 2004, page 282-83).

Many people have the flexibility to adapt to the present demands of a relationship. However many people are inflexible despite knowing that they need to change. When one person is negatively activated when seeking intimacy, his or her response can trigger vulnerabilities in the other. Long held survival behaviors become instinctively ignited and both persons start to act out. Each person intuitively responds to a perceived threat and responds to protect him or herself. "Like a shield, survival strategies are put in place to give a sense of safety and control. However, although survival strategies may be self-protective, they are often counterproductive interpersonal solutions. They tend to stimulate in the other person the very behaviors that the individual is trying to avoid, unwittingly promoting self fulfilling prophecies. When acting from survival strategies, persons often behave in self-referential and defensive ways and can become blind to the views, needs, vulnerabilities, and strengths of the other person. This insensitivity to the other person triggers the partner's vulnerabilities; in a parallel way, the partner's vulnerabilities call forth his or her automatic self-protective responses" (Scheinkman and Fishbane, 2004, page 283-84).

Individuals ignite each other's survival mechanisms, thus triggering a vulnerability cycle. Anxiety or fear cause partners like Selkie and Coleman to defend their vulnerabilities as if their survival were severely threatened. Coleman was leery of therapy since he could tell that Selkie was trying to enlist the therapist to help her continue her relentless assaults on him. A minor issue becomes reaches a high temperature and becomes convoluted and reactive. A skirmish becomes a battle and a relationship Armageddon. From the outside, it does not make sense that relatively simple issues have become so sensationalized. The probability is that the relationship has been unknowingly bound by their first order values and over time, become more and more flustered and frustrated finding their options being ineffective. Initial therapist questions: what has been the problem, what does the individual, couple, or family want to happen differently, and what has been tried previously that has not worked help reveal the confines of the first order. When an individual asserts something as if it were an unassailable truth, the therapist prompts awareness of first order limitations by asking challenging questions.

"Why not?""Or else what?""How is that so?""Why is that?""That seems to be obvious to you. Should it be obvious to your partner?"

Such questions prompt identifying survival strategies and restrictive first order rules. Only when the first order rules are identified might individuals consider their continued propriety or ineffectiveness. The therapist can implicitly or overtly challenge or even disrupt first order expectations by suggesting a solution or response that is clearly out of order- that is, in the second order. Selkie may have cultural definitions that preclude second order considerations. For example, "Pratomthong and Baker (1983) also noted that Thais avoid open expression of their feelings and thoughts to others. This value has been influenced by Buddhism which teaches that it is important to be non-expressive. Revealing emotions is not encouraged. Even though the Thai people have concerns or feelings, they learn to control facial expressions. One reason to hide feelings is to prevent trouble and to avoid challenge or confrontations. Withdrawal rather than aggressive encounters is preferred. It is expected that well-educated, well trained, and strong persons should be able to conceal emotions and control their verbal and physical expressiveness" (Pinyuchon and Gray, 1997, page 213). In Selkie's case, she is willing to openly express feelings of upset, but not feelings of need. Revealing vulnerability may not be acceptable according to certain cultural standards. Men for example are supposed to be stoic in many cultures. Needing help or asking for help may reveal vulnerability that is supposed to be hidden.

The therapist had nudged Selkie to uncover her first order standards. As the therapist began to sense her rule about expressing discomfort and the desired response from Coleman, he asked Selkie, "What would happen if when you're upset, you ask Coleman to give you a hug and comfort you?" Selkie appeared shocked as if this were an outrageous suggestion. She stammered, "But I shouldn't have to ask him to do that." The therapist pushed, "But why not? It hasn't been working your way." Selkie replied, "Cause… cause, I shouldn't have to." "Why shouldn't you have to?" asked the therapist. "Uh… because… it's obvious," said Selkie. "But it's not obvious to Coleman," challenged the therapist. "Yeah, but it should be obvious to him," said Selkie. "How come it's not obvious to him? Doesn't he love you and care for you?" inquired the therapist. "I know he loves me… but… he doesn't get it," said Selkie. "What's 'it' that he doesn't get?" "He doesn't get that he should reach out to me… do something to comfort me when I'm stressed," said Selkie. "But since he should get it, you keep on doing what doesn't work. You keep on complaining…hoping that by doing the same thing over and over something different will happen," the therapist fed back. "So how well is that working? Who is the one that doesn't get 'it"… you or Coleman? Or maybe both of you?" With a big sigh, Selkie said, "I guess I have to do something different."

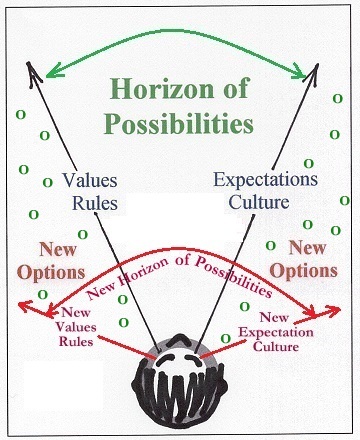

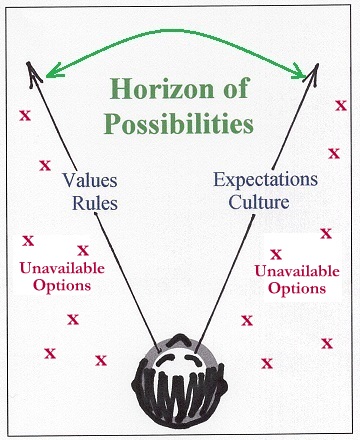

Something different is second order change. Second order change is often required to handle very "stuck" behavior sequences. Change interventions of the first order from a familiar realm of choices or what has been tried or what seems available do not work or have not been working. In the graphic below, the person has his or her field of vision or perception confined by his or her values, rules, expectations, and culture. The horizon of possibilities in the first order as limited by values, rules, expectations, and culture is all the person can see or consider.

Only as the person is able to recognize his or her restricting rules, can he or she consider new and different options in the second order. By accepting new or nuanced values, rules, expectations, or taking a cross-cultural perspective, the person has a wider horizon of choices for responses and solutions. Second order change is change that goes outside of the familiar or previously tried. It goes outside of the values, rules, and parameters that the person or persons involved is or are unconsciously holding or holding unquestioning. The person needs to become conscious of his or her rules and discover that these rules are not necessarily ironclad or even appropriate when viewed from a different perspective. A whole new set of previously unrecognized remedies or approaches becomes evident- one of which may be very effective.