12. Power & Control - RonaldMah

Ronald Mah, M.A., Ph.D.

Licensed Marriage & Family Therapist,

Consultant/Trainer/Author

Main menu:

12. Power & Control

Therapist Resources > Therapy Books > Mirror Mirror- Self-Esteem Relationships

Mirror Mirror… Reflections of Self-Esteem in Relationships and Therapy

Chapter 12: POWER AND CONTROL

by Ronald Mah

The more a person experiences power and control in his or her life, the greater his or her self-esteem. In a healthy relationship, a person exercises power and control over his or her own mind, body, voice, energy, needs, and passion. For all individuals, a sense of mastery is essential to self-esteem. In a relationship, the individual experiments with mastery and control relative to another person. For someone who has been disempowered because of abuse, neglect, trauma, and/or stress, any activity that gains a greater sense of power and control serves self-esteem. Adult relationships often are the major activities of adulthood affecting self-esteem. Conversely, any experience of disempowerment in the relationship, whether actual or symbolic can regress or re-traumatize or threaten the individual. In addition, when a person positively affects the other person- causes him or her to feel joy, exhilaration, hope. And to gain clarity, to dream, the sense of power and control is enhanced.

In their married relationship, Terry and Bert had implicit agreements in many areas over where each had dominion or deferred to the other. Terry tended to have first say in many child care and school decisions, as well as household routines and environment. Bert tended to take primary responsibility of banking, bills, and paying bills. This separation of relationship roles reflected common traditional gender roles despite their alleged more progressive egalitarian values. Actual and decision-making power however was more complex and nuanced. For example, Terry felt that she should have significant if not greater say in the vacations they took as she felt she advocated not just for herself, but also for the children. Bert felt that as the primary economic provider, he had the right to affirm or veto vacation plans or anything else that involve significant expenditures. Although Bert had deferred to Terry's day-to-day management of child care and school decisions, he wanted at least an equal say if he did not like a decision she had made. Terry felt that Bert who did not know the intricacies of daily issues was not duly informed to intervene against her best judgment. Sometimes only semi-conscious of it, these conflicts in such issues around power and control often triggered old anxieties and traumas for them. And, contributed to their divorce. After divorce, it was simplified in ways is they each had dominion over their separate households. Neither has to tolerate any criticism much less intrusion in their household. When one of them did not like how they thought things were going for their children in the other household, the feelings of impotence would often be very problematic.

The power dynamic, including who has overt and/or implicit control, and the realms of power and control affect the relationship. The balance of power and fundamental equity versus inequity in the relationship affect self-esteem for each partner. "…a working definition of relational equality that extends beyond the division of labor to the emotional foundation of the relationship and includes four interrelated aspects (Knudson-Martin & Mahoney, 2009):

Relative status: Who defines what is important? Who has the right to have, express, and achieve goals, needs, and interests?Attention to the other: To what extent do both partners notice and attend to the other's needs and emotions? What do they do when attention is imbalanced?Accommodation patterns: Is one partner more likely to organize his or her daily activities around the other? If one person automatically accommodates, how do they attempt to justify these behaviors?Well-being: Does one person's sense of competence, optimism, or well-being seem to come at the expense of the other's physical or emotional health? Does the relationship support the economic viability of each partner"(Knudson-Martin and Mahoney, 2009, page 6).

Conflict in relationships may come from struggles against experienced inequities between the members. The therapist seeks to reveal the explicitly expressed power relationship in comparison to the actual power dynamic. An agreed balance of power needs to be agreed upon and then actuated in the relationship. In order to find this balance, symbolic experiences and expressions of power and control need to be identified. These will come from exploring cultural and family-of-origin values that may have been internalized unconsciously or semi-consciously. In a classic example of stereotypical gender values when they were still married, Terry felt that her domain rightfully included the kitchen and cooking, the social calendar, the basic child discipline and management responsibilities, and household chores. Bert felt that his domain rightfully included financial decisions, the cars and garage, coaching the partners' sports, and the barbeque! When he interjected himself into child-raising decisions, Terry felt her power and control violated. When Terry made expensive purchases that challenged Bert's budgetary decisions, he felt his fiscal dominion invaded. Both of them as partners had believed in and owned traditional values of overall patriarchal preeminence with matriarchal responsibility over partners and household.

All components of self-esteem are interrelated. Losing power and control was also experienced as disrespectful- an indication of negative significance. In this situation, the therapist set aside personal preferences for a more egalitarian balance between heterosexual couples to work from Terry and Bert's more traditional roles. These were their ideal self partner definitions. As it turned out, as long as Terry had felt respected (positive significance) by Bert (who is significant to her) in her role as the traditional matriarch, she was fine in the relationship. Bert had been willing to do this as it fit into his self-definition or ideal self as a husband. A few minutes of therapy would have sufficed to identify his real self behaviors (including staying out of her domain) that would conveyed his respect to Terry and her role. The therapist if conducting therapy prior to their divorce could have facilitated their re-connection by presenting positive alternatives that distinguished impressions and facts. Bert had the impression that Terry had disputed his role as patriarch. Terry had the impression that Bert had tried to circumvent her parenting. The reality turned out to be different. Communication work could have reinforced jointly held values: "Avoid hurting your partner; maintain appreciation in the relationship; don't make assumptions about your partner; and don't give up (Mozdzierz & Lottman; Hawes, 1982). The goal of this intervention is to increase each partner's assumption of responsibility in the relationship. When individuals can be more accepting of the consequences of their behaviors they are better able to recognize their own limitations. Furthermore, they can better identify and meet the needs of their partner while contributing to a more egalitarian relationship. The outcome will be partners who have a strong feeling of mutual existence and equality in the relationship" (McCurdy, 2007, page 286-88). Bert and Terry assumptions could have been examined in therapy and proved inaccurate. The therapist could have validated Bert and Terry's determination to work through their issues by using therapy. Bert and Terry would have been held responsible for their role definitions and the consequences of how they communicated with one another. Interestingly, their resolution would not have been of an egalitarian relationship. They would have re-settled contentedly into their previous hierarchal relationship with Bert as the patriarch. Rather than achieving equal balance of power and control, relationship equity would have been achieved through mutual respect. Current therapy with them should include if possible, mutual respect as well.

In addition to feeling significant and holding oneself to ones ideal self, healthy self-esteem still requires the individual to have a sense of power and control. Intuitively, any individual in a relationship realizes that there are power and control issues at play. Upon closer examination, it often becomes evident there are control problems that the individual has with the other person's attempts to get power and control. Oftentimes, an individual actively seeks more power and control and unfortunately, does so in a disruptive manner. The disruption may be because behavior triggers the other person's issues with power and control. Alone or in a relationship, the individual is supposed to seek power and control in life, perhaps because power can be an antithesis of being a victim. A better education, a good job, better income are all things most individuals struggle for. Success gains greater power and control in life. The struggle for the nonmaterial benefits in life: serenity, fulfillment, security, a sense of purpose, or spirituality can be seen as gaining power and control in one's emotional and psychological life. The individual applies to the relationship the skills (or lack of skills) from lifelong struggles for power and control. Personal struggle for power and control may not have integrity for the relationship. In other words, the other person, partner, or children may be harmed. Intimidation or bullying may occur. Rights may be rights ignored and others disrespected. Others might lose their power and control as the individual asserts his or her power and control. Power and control can be gained by being a victim. Key to self-esteem is whether the ideal self is honored or betrayed in gaining power and control.

The need to take care of power and control issues can be extremely compelling. The individual may develop an ideal self that places power and control as an absolute first priority, no matter the cost. A cultural attitude that promotes gathering power and control by taking care of No. 1 at the expense of others can become acceptable and even desirable. People begin perceiving the world as being split between winners and losers, with the implicit and sometimes overt message that losers are just getting what they deserve. If the individual finds that interactions with another person has become a power struggle, then something is fundamentally wrong. Unresolved issues with power control can contaminate the individual's appropriate struggles for power and control in a relationship. The individual may act out with greater intensity because of personal history. The therapist should uncover the personal history with power and control for the individual, partners, or family members to better understand their needs. However, compassion for old challenges does not mean any individual is supposed to accept negative behavior. Boundaries must be established for healthy power and control. As an individual seeks power and control, he or she may become vulnerable to self-injurious choices to doing abusive or dangerous things. Power without sensitivity and control without responsibility is dangerous to self and others politically, socially, for the couple, within the family, and for oneself. In addition, the individual's struggle for self-esteem and power and control occurs in various contexts that may not be receptive and possibly, may be antagonistic.

Gender equality has progressed over the years, which has lead women to challenge traditional models of heterosexual dynamics. This can occur with any relationship, but may be more pronounced with immigrant couples. "…women test their limitations with their partner by trying new behaviors and ways of communicating that were previously avoided or considered unacceptable in their native country. We call this process pushing the gender line. Women subtly push their husbands to listen to their opinions, do what they want, or to accept their influence in decision making. This process begins as men relax their efforts of maintaining and keeping the power. It may be influenced by who makes the money. The initial gender line represents the previously set gender structure that governed couple interactions. As partners become aware of women's rights and new relational options, they begin to evaluate and alter their personal gender culture and women increase their power and influence in the marital gender structure" (Maciel et al., 2009, page 19). The greater social-cultural environment often qualifies the partners' capacity to practice more egalitarian values and behaviors. "Despite expectations of mutuality, socialization patterns and the male dominant social structure reinforce male power and limit options for women. Many of the participants in this study are aware of the influence of societal processes on their lives and are troubled by the contradictions between their egalitarian ideology and inequality in their relationships. Arman says, 'We believe in it [equality], but in reality men want to have their ways.'" This statement by Moghadam et al., (2009, page 46) in reference to Iranian couples, can be applicable to many couples in the United States. Maciel et al. (2009, page 10-11) discussed how immigration affects gendered power. The commentary also may resonate with the experience of non-immigrant couples and prove informative for the therapist. "How immigration affects gendered power in couple relationships rests on a variety of factors and may vary considerably depending on social class (Inclan, 2003). Immigrants from what Inclan calls the bourgeoisie class may be more able to accept the less traditional gender ideology of their new country than poor immigrants. Poor immigrants may have to renegotiate gender roles due to necessity, for example the father takes care of children while the mother goes to work because she can more easily find employment, but this may cause tension between the partners (Falicov, 1998). Changes in work roles are frequently cited as the impetus for conflict and change regarding power positions among immigrant couples. Hondagneu-Sotelo and Messner (1999) found immigrant life in the United States diminished Mexican men's patriarchal standing. Partners had more conflict, but also a more egalitarian division of labor. Men tended to display machismo and other forms of masculinity to compensate for their lack of status in the larger social structure, but this change was more related to institutional than family power."

The therapist should explore the potential influence of class relative to power and control issues in a relationship. In particular, the therapist should be alert to any recent or generational changes. There may be relevant disparity in the class status between the two individuals. Class status may be inherently or directly related to gender roles. Traditional male dominance or financial control as the traditional male breadwinner may result in status disparity between partners. An individual whether male or female, heterosexual or homosexual with greater income may have greater experienced and activated equity in the relationship. Change in work status, especially becoming unemployed or being under-employed as experienced by immigrant partners can trigger conflicts in many couples. In particular, a traditional heterosexual couple can be unbalanced when the male partner becomes unemployed or makes significantly less money than the female partner who has a high status job. The therapist may find anxiety or insecurity about diminished status or power and control as the instigating issue in the couple. "The link between marital power dynamics and men's fit within the dominant social structure was also evidenced in a study of Brazilians in the United States (DeBiaggi, 2002). As men became more able to use English and adopted other mainstream cultural values, they displayed a heightened ability to be more liberal in their stance toward gender roles. Awareness of laws and protections offered to women in the United States often increased immigrant women's courage to seek change in their marital relationship. A number of studies report that the economic need for women to work has considerable influence on marital power relations. In Hondagneu-Sotelo's (1992) study, Central American women who found jobs in America began to experience and observe American gender behaviors and ideals through their jobs and desire more equality" (Maciel 2009, page 10)

Greater English language proficiency, cultural adaptation, acquired political knowledge, and increased economic viability provide greater power and control for immigrants. For all individuals, similar gains would increase personal and social capital. The therapist should promote appropriate gains in power and control for individuals in and outside of relationships. One or another individual may bring up issues and problems in therapy that are not directly relevant to the relationship. They may be work, social, or other situation where the individual sense of or actual power and control has been challenged or harmed. The therapist may find exploring the issues or problems relevant to the individual's overall sense of diminished power and control. As a result, power and control issues between individuals over household or child rearing issues might resonate symbolically and more intensely. The therapist might encourage an individual to get education or training that may gain him or her advancement at work. Potentially empowered by a promotion or by being in an affirmative process of self-improvement, the individual may gain self-esteem. This in turn may gain respect and validation from the other person, while possibly defusing the level of tension in the relationship.

Acclimation or acculturation to American values however varies. "The men, however, were less likely to mix with Americans and remained with other Latino men who still held gender ideologies from their country of origin. In a study of Korean immigrants, Lim (1997) found that women were also less willing to be obedient than they had been in their country of origin. Though patriarchal beliefs limited the degree to which these women would challenge their husbands, they perceived more right to demand their husbands' help in the home. Yu (2006) found that women who immigrated to the United States from Maoist China had the opposite experience. They found gender roles more traditional in the United States than expected in China. Yet they were willing to accept them because doing so benefited the stability of their family, even though it disempowered them in being able to work, study, or engage in other life activities" (Maciel et al., 2009, page 10-11). Participating in couple therapy challenges the isolation of the individuals and couple. As with the immigrant men who associated with others with similar values, the individual or the couple that does not associate with and consequently does not experience different ideas and behaviors. Lesser willingness to be obedient to their husbands was balanced by immigrant women still influenced by traditional patriarchal expectations. Cultural values about the stability of the family also influenced women's willingness to seek personal independence. Many immigrant women as both men and women in general may balance between gaining power and control personally and gaining it through family benefit or causing harm.

The individual or couple's experience of benefit or harm can derive from social circumstances. For example, racism and discriminatory experiences impact African-American and other people-of-color couples. Racist politics and economic discrimination can make it difficult for African-American men to adequately fill socially defined gender roles. "Marriage could not protect Black women from economic exploitation and the need to labor outside the home in the same way it protected many White women (Blee & Tickamyer, 1995; Broman, 1991; Furdyna et al., 2008). Although African American men have a history of doing more household labor than other men (Blee & Tickamyer, 1995; Broman, 1991), it is unclear whether African American couples are markedly more egalitarian than White couples. Women still do the majority of the family work (Hill, 2005). Black women reported no more ability to influence their husbands than White women in Steil's (1997) study." African-American men, especially those with lower social status commonly make demonstrations of power and control. Treated as irrelevant and subject to indignities in society, African-American as might men of other ethnicities attempt to compensate with ill treatment of partners. "However, a woman's sympathy for his experience of powerlessness may limit her willingness to address issues important to her… These couples face external challenges together, drawing on spiritual, family, and community resources (Marks et al., 2008)" (Cowdery, et al, 2009, page 27-28).

Cowdery et al. described an African-American couple, Terrell and Keisha who pull together for the good of the family (page 32). Although, they generally have a more equal relationship than some other couples, "the inequality that Terrell feels in the larger society also reinforces invisible male power in their marriage." Terrell feels that he has to defer to many people because he is an African-American man. He dummies up because he thinks they- white people and/or people with power or authority cannot deal with a black man knowing more than them. While he dummies up for white people, Keisha dummies up for Terrell "cause no man, no Black man wants a wife, a woman, who knows more than he does." She restrains her power in the couple to let Terrell feel he at least has power in their relationship if not in society. "This response to societal constraints may have serious consequences on their marriage because it is rarely discussed." Terrell is unaware that she feels and acts this way. The therapist needs to examine the partners and couple's valuing of individualistic versus communal benefit. The therapist needs to self-examine for his or her values as well. He or she may unknowingly promote mainstream American values that often have greater emphasis on individual fulfillment versus many traditional cultural values emphasizing individual sacrifice and submission to family needs. This can prove problematic for therapy maintaining cultural integrity. Therapy may require a multi-cultural and cross-cultural approach to be successful.

COMMUNAL POWER AND CONTROL

The therapist should explore if and how individuals may share power. Communal power and control may be compatible with or reflect an individual's family-of-origin or cultural values. Cowdery et al. (2009 page 27) discusses "Harambee" which is an African principle meaning "let's all pull together," which may also be relevant to others from other ethnic, religious, or cultural backgrounds. The African-American experience has frequently of necessary been primarily about survival. This may be differentially relevant for mainstream Americans with variable experiences depending on personal and/or family-of-origin history that emphasize equal power based on individual rights. In addition, one or both partners in an African-American couple may not have experiences of communal working together from their respective families. The family model and the couple's model may have been of independence and thus, the ethnic stereotype may not be relevant. However, "Pulling together in African American households may have been the best way to survive and fulfill the duties of parenting partners. The goal was survival in the face of tremendous obstacles." The principle and practice of working together may be relevant to a person of any ethnicity where survival as a family was tenuous. Outside pressures such as social injustice and economic pressure on the individual, couple, or family can be intense. This can result in relationship conflict, alcoholism, drug abuse, or violence as the individual battles powerlessness in the greater community. The therapist can "help couples join together to fight injustices rather than directing their anger inward or against each other. Once couples recognize that the sources of their problems are connected to socialization and dominant societal messages, they will be more able to develop collaborative ways of addressing these issues (Pinderhughes, 2002)" (Cowdery, et al., 2009, page 36-37). Individuals will usually unify to fight threats to one or another in the invested relationship (as long as the other person is not making the threat), the couple, the family, or the children. If the therapist can activate individual, couple, or family's power and control to counter a threat, the relationship often improves.

PASSIVE-AGGRESSIVE BEHAVIOR

The individual needs to experience the consequences of his or her choices. Positive choices that lead to positive consequences helps the individual learn empowering principles. However, when the individual make poor choices and suffer negative consequences, he or she usually learns the most. It is said that a wise person learns from the mistakes of others; the average person learns from his or her own; and the fool does not learn despite repeated mistakes. The wisdom that the other person or the therapist seeks to give the individual usually comes from prior personal mistakes that were made while ignoring wisdom being offered by others! As the therapist, it may be necessary to let clients make negative choices and let negative consequences happen. The easy part for the therapist may be training individuals to give and get positive consequences for making positive choices. Some individuals are also willing to take responsibility for negative choices and take their negative consequences. Therapy helps them understand why they make poor choices and helps them make better choices. Difficult therapy and a difficult relationship often involve an individual who otherwise feels chronically disadvantaged and disempowered. This individual may especially need to experience the consequences of both their positive and negative choices. Such an individual can become very adept at avoiding the consequences of negative choices- deludes him or herself that he or she can avoid consequences. Avoiding responsibility for poor choices eventually causes greater and greater loss of power and control, as well as respect from and intimacy with others. To maintain a semblance of power and control, he or she can gravitate to aggressive behavior with "plausible deniability." The therapist needs to identify and name this highly destructive strategy of passive-aggressive behavior in the individual, couple, or family. They need to be exposed as attempts to gain power by disempowered individuals. Four terms- the Four "P's" of Passive-Aggressive Behavior" can summarize the cognitive aspect of the process: Power, Passive, Permission, and Punish.

POWER: The individual experiences a perceived lack of Power relative to his or her partner in the relationship, but does not feel safe or secure enough to confront the partner directly;PASSIVE: Despite being upset and angry, it can lead to a Passive response by the individual;PERMISSION: The passive response or lack of response, implies Permission to the partner to continue the behavior and incorrectly think everything is fine;PUNISH: The individual gains a resentment. With passive implied permission from being disempowered, he or she feels entitled to Punish the partner.

As discussed, there can be many reasons for the individual to feel a lack of power and not feel safe to overtly and assertively respond. The individual may experience two options: one, to allow oneself to be dominated and controlled- that is, to accept powerlessness and victimhood; or two, to fight back. Some individuals, communities, groups, and societies feel compelled to accept inferior status in the face of dangerously totalitarian authorities and/or because of experiential history of being disempowered. Other individuals respond with habitual oppositional, defiant, and rebellious behavior whether or not they are actually being oppressed currently. In the relationship, a person may be stunned to find him or herself the target of resentments that he or she can see no reason for. The aggressive individual perceives violating behavior- a projection onto the other person as the new potentially dominating person. If the person finds submission unacceptable and overt aggression too dangerous, then passive-aggressive strategies become the third option. Although actual power may be further lost with passive-aggressive behavior, power and control are so psychically compelling that the illusion of power and control becomes sufficient. The illusion of power and control comes from aggravating or frustrating the other person's desires, serenity, stability, and other psychic states. It is a false reflection of true power and control. Habitually oppressed children, individuals, and communities engage in forms of relational guerilla warfare, while ostensibly complying with the oppressor/target's demands.

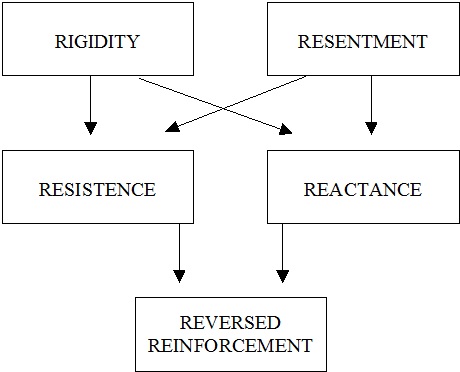

Figure 1: A Model of Passive-Aggressive Behavior (Fine et al., 1992, page 476).

"The P-A (passive-aggressive) style involves behavior that is inflexible and maladaptive. Stubbornness and a rigid emphasis on autonomy are common descriptors of P-A style. Rigidity makes it difficult to adjust to change, because it is difficult to learn from experience if persons believe that no one can tell them what to do or how to do it. Thus, this rigidity places them at risk for a variety of life difficulties when forced to live in an ever-changing world. People high in passive-aggressiveness tend to be authoritative and dogmatic, holding rigid beliefs about how the world should function. Their rigid insistence things be done in a certain way produces a low frustration tolerance. When other people do not conform to these beliefs, irritability and resentment are likely to follow" (Fine et al., 1992, page 478-79). Slow, delayed, and incomplete responses along with no response become the tactics for aggression. Gossip and hidden or covert acts of disobedience or defiance serve as undercover attacks. Hidden messages, spoken and unspoken words, covert communication, and the silent treatment also constitute pinprick assaults. Inconsistency, erratic reliability, and insincere excuses or apologies are characteristic of the passive-aggressive individual.

"Passive-aggressiveness often leads to an oppositional rebellion that can be expressed in several ways:

(1) procrastination,(2) verbal protests,(3) "forgetting" certain tasks,(4) slow performance, and(5) resenting useful suggestions.

Individuals high in passive-aggressiveness may initially agree to cooperate with others and then "back out" at the last minute. This oppositional attitude is similar to the notion of reactance. Reactance is aroused when a person perceives a behavioral option to be eliminated or threatened with elimination. Reactance can be expressed as indirect behaviors, hostile attitudes, and increased preference for threatened choices. When a behavioral choice is threatened, reactance serves to restore a person's perceived freedom of choice. People high in passive-aggressive are often invested in preserving their autonomy… individuals who display reactance to low-threat situations often report low-esteem, high self-consciousness, and attribute loss of freedom to internal causes. These same qualities describe the P-A coping style, although internal attributions for failure experiences occurs only during periods of self-doubt… Passive-aggressiveness is often associated with feeling threatened, out-of-control, and powerless in many situations. Hence, people with P-A tendencies may perceive situations as threatening and tend to respond in a reactive manner in order to regain control, sometimes responding to demands with passive revenge… They may feel that they can maintain a sense of control by responding in an oppositional manner, and, thus, derive satisfaction from what appears to an outsider to be a negative outcome" (Fine et al., 1992, page 480).

If confronted about coming late to pick up or drop off the kids, Bert may deny any ill intention. Likewise, Terry may claim innocence about the children overhearing her complain about Bert to a girlfriend. If confronted, about his or her passive-aggressive behavior, the individual asserts excuses with "plausible deniability" of wrongdoing and ill intent. The other person may hear apparently positive words and intentions, but find covert aggression to be insidious and destructive of intimacy. He or she may be confounded by the denials and pseudo-logical explanations of the passive-aggressive individual. The therapist must act as to critically disrupt the passive-aggressive dynamic. As a third person observer entering the passive-aggressive dynamic of the relationship, the therapist can identify and confront the behavior. The therapist may see such behavior in the individual client's rendition of behaviors outside of therapy, or may observe it within the sessions of couple or family therapy. The passive-aggressive individual may attempt to continue denial and use passive-aggressive tactics on the therapist. This would include attempts to terminate therapy prematurely, "forgetting" appointments, and the silent treatment that may have been so effective against another person.

The therapist sets boundaries against such responses, or perhaps uses a paradoxical intervention. For example, the therapist can use prediction and name how the passive-aggressive individual will attempt to sabotage the therapy to deny the characterization. The passive-aggressive individual often resents having to follow rules set by others. Following rules and observing boundaries set by others is an intolerable loss of power and control. If compelled to behave as others require, the passive-aggressive individual becomes angry. He or she feels misunderstood and unappreciated, and as a result becomes cynical, skeptical, and mistrustful. With fragile low self-esteem, the individual with passive-aggressive characteristics often end up resenting and being critical of others who he or she perceives as successful. Resentment and jealousy can tend toward paranoia, which then can cause relationship problems. The passive-aggressive style includes obstinate resistance to fulfilling expectations or demands including those the individual may be okay with. With poor self-perception of being frail, fearful of change, and with low self-esteem, the individual often feels too weak to overtly refuse to comply or express dissatisfaction. Dawdling and procrastination are among forms of passive-aggressive inaction. The individual often cannot accept advice and suggestions despite rejection causing personal harm or distress. Even if the individual appears to comply or be agreeable, underneath lies defiance and rebellious attitudes.

"An additional aspect of resistance is the P-A tendency to maintain oppositional attitudes towards authority figures. Resistant persons fear a loss of control when interacting with people in authority. Hence, those with a P-A style may respond to authority figures in a defiant and resistant manner across many situations" (Fine et al., 1992, page 479-80). The therapist is can become the authority targeted as the new opposition. If the therapist were to confront the passive-aggressive individual or agree with his or her partner, defiant and resistant behavior may follow. The passive-aggressive individual may be very fluid in transferring his or her hypersensitivity and hyper-vigilance or paranoia from some person at school, the partner, or another family member to the boss, and then to therapist and back again. The individual's partner and the therapist may be flummoxed by behavior that seems irrational. As opposed to seeking positive reinforcement the passive-aggressive individual seems to seek negative reinforcement. He or she seems to feel more powerful and gratified when things go badly. It appears that he or she is pleased with mishaps because others feel sorry for him or her. Passively allowing problems to develop rather than affirmatively addressing them gives the passive-aggressive person justification to become angered and resentful. "Such negative experiences allow people with the P-A style to feel that they can understand and control the world because they can always expect and usually find an undesirable outcome. When negative events happen to persons with a P-A style, external attributions are common and others who make demands upon them are blamed. Self-statements like the following can make a failure experience feel gratifying: 'I told you so,' 'See, I knew it wouldn't work,' and 'That'll get them.' These statements allow them to externalize the blame for their difficulties. Through the reversed reinforcement system, those high in passive-aggressiveness are able to retain control over their lives, even if only through maladaptive and indirect means" (Fine et al., 1992, page 479-80).

When something bad happens to the partner or someone else, the passive-aggressive individual may feel a sense of justice. The therapist will find him or her not only being defiant and uncooperative but also relishing the therapist's frustration. The passive-aggressiveness individual often becomes resentful if he cannot control things. The other important person easily becomes the target of the resentment, since the other person may expect mutual control and assert him or herself in relationship decisions. The passive-aggressive individual also therefore becomes upset if the therapist asserts control in therapy. The individual will seek control of issues, decisions, and the other person indirectly. At the same time, leaving decisions to someone else- the partner in particular, reserves the passive-aggressive individual the right to be resentful of the decision and the decider if something does not work out satisfactorily. As mentioned earlier, the therapist awareness of passive-aggressive dynamics and behavior enables him or her to identify and confront the individual. The therapist for example may find playing close attention to his or her counter-transference with Terry and with Bert- specifically, annoyance and frustration useful. This can lead to confrontation which may break the negative dynamics directly, or may re-direct therapy to uncover the source of the individual's passive-aggressive style.