SE chapters 6-10 - RonaldMah

Ronald Mah, M.A., Ph.D.

Licensed Marriage & Family Therapist,

Consultant/Trainer/Author

Main menu:

SE chapters 6-10

for Parents & Educators > Articles > Self-Esteem Series

Building Self-Esteem in the Adult Child System

Chapters 6-10

Chapter 6: Sigmund Freud Meets Jiminy Cricket, From Acceptance to Moral Virtue

SELF-ESTEEM RESILIENCY -- ACCEPTANCE TO MORAL VIRTUE

Last month, we looked at how significance -- the messages of worth that are given to children by the significant people in their lives, is so powerful in creating Self-Esteem. As parents are able to take care of their own needs and give to their children the acceptance messages that they need, their children Self-Esteem tends to grow. However, parents realize that they cannot always be there to support the children. That they cannot always be there to always confirm to the children that they are important, and that the things that they do are valuable and appropriate. Children not only need to feel loved by the significant people their lives, but also to feel love for themselves. From the movie "The Greatest" comes the song about Muhammad Ali, "The Greatest Love of All" sung first by George Benson and more recently, by Whitney Houston. In this song, it said, "the greatest love of all, is to learn to love yourself." Well-loved toddlers live this song's message totally!

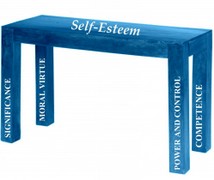

While we enjoy how toddlers seem to love themselves so much, we also notice that some toddlers are more vulnerable to the negative and positive opinions of others. In addition, there are some children and some adults who fail to love themselves. For some of them, it is clear that their low self-esteem comes from a lack of the positive messages from there are adult caregivers -- a lack of messages of significance from their significant people. On the other hand, why do some children and some adults fail to love themselves -- who do not have self-acceptance, despite being well loved and admired by many other people? Also, there are those children who clearly love themselves when they are younger, but lose that love for themselves as they grow up? The critical question becomes how do toddlers, children, and adults develop the emotional/psychological resiliency to continue to love themselves (the core self-acceptance) despite the sometimes esteem-harming negative socialization that they experience? How can parents armor children to develop Self-Esteem and to keep that Self-Esteem? Part of the answer lies in another of the four components of Self-Esteem -- in what Coopersmith calls moral virtue.

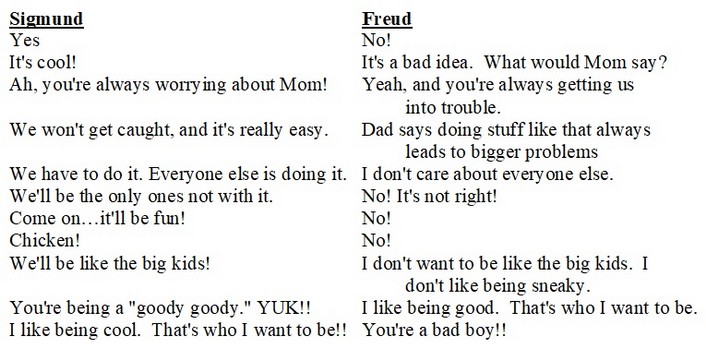

JIMINY CRICKET AND YOUR SUPEREGO

As children grow up, they develop a sense of what is right and wrong. They develop a group of values... a set of shoulds and should nots... what a good boy or girl and what a bad boy or girl does... a pattern of behaviors that is virtuous. This is what makes up their morality, their conscience, the superego (from Freud), the Jimniny Cricket (from Disney's Pinocchio!-- following Pinocchio and guiding him) that tells children and adults whether or not their behavior is appropriate or inappropriate. This set of values, of course is developed from the guidance of their parents initially; later, from the influence of other significant adults such as teachers; eventually, more and more as they move toward adolescence, from their peers (oh oh!); and continually, from the messages of the society at large -- especially from the media. This is why little boys and little girls continually ask, "Is that good? Is that bad?” or "Is he/she a good guy? Is he/she a bad guy?" Children from their youngest look to their parents for guidance in the world. "Should I touch that? Is it too hot? Will it hurt? Will he be mad? He/she nice?" As a consequence, children's morality initially is made up of their parents’ morality.... and of their parents' frustrations, fears, and, unfortunately, their parents' hang ups, prejudices, and ignorance. Children need not only to learn the morality of their parents (hopefully, a positive morality), but also to be able to internalize it in a positive manner.

Children accept the morality of their parents and their own. However, the natural process of growing up causes them to question that morality. This is healthy if there is a healthy core morality that the child will make adjustments to as he/she lives life. This, however, can be dangerous if the core morality is not healthy or is fragile. In addition to getting the approval of their parents and other adults, children need to be guided to also be able to give themselves approval for their decisions and behavior. In the community of other children, and later, in their future communities as teenagers and adults, they will not be getting the approval of their parents (who cannot be normally present). In fact, they may be getting the very clear disapproval of the others in the community. "That's dumb!" "You did what?" Their ability to feel good about themselves will be dependent on their ability to make the decisions that allow them to follow through with what they feel they should do. In choosing to do what they feel they should do, they will often feel the disapproval of others. Their ability to approve of themselves -- to accept themselves is critical to their Self-Esteem.

THE IDEAL SELF VS. THE REAL SELF

The ideal self vs. the real self are very powerful concepts to help build the sense of self-acceptance -- to develop the powerful moral virtue that allows children to maintain their Self-Esteem into and through adulthood. The ideal self is the composite of all the good things that an individual wants to be; it is the definition of the person who totally lives up to the values that he/she holds dear; it is the good... no, the perfect little boy or little girl... the perfect person that each person wants to be. The real self, on the other hand, is made up of what each individual actually does. If the ideal self says to be kind and giving, and the real self is able to be kind and giving to a friend, or to a stranger, then Self-Esteem goes up. The real self has been able to live up to the standards of the ideal self. However, if the ideal self says to be kind and giving, and the real self is not kind and does not give... to he is/her little sister... or, for example, to that homeless man on the corner, then (no matter what the political perspective, how much theory about alcoholism and drug abuse one possesses, or how many other ways the individual gives to charity and even perhaps directly gives to organizations that support the homeless) there is a mismatch between the real self and ideal self -- there is tension between the real self and the ideal self. And, with this tension, Self-Esteem tends to go down. In other words, even as the ideal self seeks to be humane, the real self is human. Failing to realize and accept the humanity of the real self causes a loss of Self-Esteem.

With these two concepts, there become two directions with which to build your child's Self-Esteem. First, is to build the ideal self in a manner that is healthy and productive. Some individuals' ideal self are... stupid! Or, even worse, dangerous. For example, in the adult world, there are parents who define being a good parent as being the perfect parent... who define good parenting as never allowing their children to have stress, or feel disappointment... who define being good parents as never expressing anger at their children -- to never raise their voice. These parents expect themselves to be perfect, and in doing so, deny their humanity. In denying their humanity, they create an unrealistic and unattainable ideal self. And, as the real self fails to live up to perfection, their Self-Esteem plummets. What kind of ideal self is unrealistic and dangerous to a child? One only has to look at how adults express their frustrations at their children. As they try to over manage their children's behavior, parents guide their children to define a distorted ideal self. If children acquire ideal selves that says they should be able to sit still, touch only with their eyes, remember what was said two weeks ago, not be sensory motor, speak always in a quiet voice, eat their vegetables, not stare when they are curious, learn to read before they are four, never spill, love to bathe, be able to suppress their energy, remember to put things away, be able to anticipate parents' moods, get straight A's, to " know what I mean!"... their ideal self may not allow them to be fallible children! (For some children, some of these things are impossible, and you practically have to tie them down to get them to be still, or force feed them intravenously to get them eat their vegetables!). They will be in continual danger of failing the ideal self the parents had given them -- they would be in continual danger of failing themselves. On the other hand, if parents can guide their children to define a healthy and realistic ideal self, then children will be able to fulfill themselves and develop and keep Self-Esteem. Such an ideal self would include a child that makes mistakes but continues to strive; who has energy and passion and develops appropriate boundaries for expressing them; is sensitive to others but respectful of him/herself; who has a joy for living and learning; and, although he/she may not eat his/her or vegetables all the time, takes good care of him/herself with an healthy lifestyle. In other words, a good person -- not a perfect human being; someone who accepts his/her her humanity; and, is a good citizen in the community.

Striving to meet the standards of the ideal self requires developing skills and other traits. This can be conceptualized in the development of the real self. If the ideal self is realistic and healthy, then the real self can be developed to meet its standards. If the ideal self is supposed to express itself but with understanding and compassion, then the real self needs to develop healthy communication skills. The real self would need to learn how to say please and thank you, how to appropriately use eye contact, adjust the tone of their voices, use or avoid physical touch as appropriate, and understand personal space as it is culturally and individually defined. The real self would be trained to recognize differences between one situation and another situation -- including the cultural demands of different communities: of the library vs. the grocery store; of the school vs. the home; of home vs. Grandma or Grandpa's; of a particular ethnic community vs. another, and adjust their behavior to fit. The real self may need to learn how to express itself physically in ways that are effective personally, but are not intrusive to others' needs, and are socially appropriate.

If there is an ideal self need to be powerful, the real self needs to find a way for that power to be expressed in a healthy form -- which may be as a leader, and a builder, or perhaps in martial arts among other ways. If it is accepted that the real self cannot sit still and needs to be sensory motor, then the ideal self can be adjusted to say that the individual will take care of these motor kinesthetic needs in appropriate ways. Then the real self can be trained to find ways to physically active appropriately -- gymnastics, dance, soccer, football...or, running around in circles around the tree! The match and mismatch between the ideal self and the real self creates crises for children, but they also create the opportunities for real growth.

A MIDDLE SCHOOL CRISIS

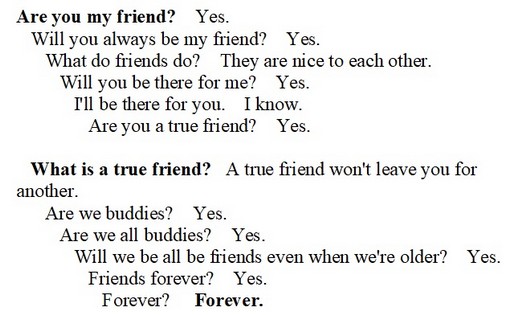

A couple of years ago, my daughter, Trisha faced a crisis regarding her ideal self and real self. She along with several other girls had grown up together since Kindergarten. The girls had always gotten along relatively well. However, it was now middle school. And as happens often times in middle school, preadolescent and adolescent dynamics begin to take place. In this particular case, several of the girls decided that they were the in crowd -- the "cool" girls. Many women remember this time with a great deal of pain when some clique deemed them worthy or unworthy. In order to have an in crowd, you also need to have an out crowd -- or, at least a scapegoat. My daughter was not picked to be the scapegoat. However, one of the other girls, Shelley was picked. Like Trisha and the majority of the other girls, this girl had grown up with the others since Kindergarten. Everyone had more or less gotten along with Shelley even the normal personality conflicts that kids can have.

Now, however it was different. It was a very difficult time for Shelley: the "cool" girls talked about her, shunned her, and let her know in so many ways that she was inferior to them- rolling their eyes, a snicker here, a snide remark there, a snort, a look... Given all the intangibles that make up one's rank and status, Trisha could have joined in with the in crowd. She had status as a high achieving academic student, and as an athlete because she played basketball -- at this school, basketball was a big deal. We have heard about the clique through the school grapevine. When we came to school one day, we noticed that Shelley was by herself on one side of the courtyard while the in crowd girls were on the other side, happily and smugly feeling superior. We noticed that our daughter Trisha had not joined the in crowd, but had instead stayed with Shelley; she was the only girl who had stayed by Shelley.

Later on as we were driving home, we asked Trisha what was going on. She replied "Oh, those girls, they think they're so special. They're being mean to Shelley." We asked her, why wasn't she hanging out with those special girls -- the in crowd, the elite clique. I will always remember the look on her face when she heard this question. She had a look of surprise on her face and she replied, "I can't do that to my friend." I was stunned... Wow! And proud. She couldn't do that to her friend... She couldn't abandon or betray her friend!! It was so obvious to her that she shouldn't do that. But, it would have been so easy to do that to her friend. She had stopped herself -- something had stopped her from doing that to her friend. Most of the other girls had done it to their friend! I told her, "I'm very proud if you. Not just for being nice to your friend. But because you chose to be a friend even though in doing so, you put yourself at risk to have those girls be mean to you too. I'm glad you made the right choice. But I'm even more impressed that you had the courage to make the right choice. Because, you know, I don't know that when I was your age if I would have had the courage to stand by my friend like that and risk being ostracized. And, you know what else? There were adults right now, who still don't have the courage to be a friend like that. You should be very proud of yourself." A small smile spread across Trisha's face, and there in the car, it seemed that I saw Trisha visibly grew larger and more powerful. (Whenever I remember or recount this story, a lump grows in my throat and my eyes become misty! I'm getting misty next to my keyboard right now! Oh my!... Out of the mouths of children!).

When Trisha had said "I can't do that to my friend," she was not responding to the situation because of her mother or father or some teacher had told her that this was the right thing to do. Much more importantly, she had internalized a set of values about what it meant to be a friend. To do other than stand by her friend would not have been a rejection of other people's values, but a betrayal of her own values. Her concern was not that she would seem less worthy in our eyes, but that she would have seen herself as less than she wished to be. Her ideal self had said that as a friend, it meant she had to stand by her friend. Whether or not Shelley was worthy as a friend was not relevant. For Trisha it was about Trisha -- who she wanted to be. And, her real self stayed with Shelley even though it meant personal risk to herself -- a personal risk she could easily avoided by hanging out with the "cool" kids.

When children and adults have well thought out and secure ideal selves, whether or not there is anyone else to watch them or to judge them, they hold themselves to the ideal self. They hold themselves to act in a manner consistent with the values of the ideal self. To not do so would be detrimental to their sense of Self-Esteem. Even as this challenges them, even as this endangers them, their self-definition still requires them to find a virtuous way to act. They search for a way that the real self can follow through. Moral virtue encourages behavior in a person that allows him/her to accept himself/herself because he/she can behave in a consistent manner. Moral virtue is what a person carries with them when there's no one around (especially when the parents are not around) to contend with the tremendous pressure and influences in the world that would tell them to do other than what is virtuous. Jimniny Cricket had reminded Pinocchio to hold fast to his moral virtue when he was tempted by the immediate promises of Pleasure Island.

THE IDEAL SELF/REAL SELF -- POWER RANGER VERSION

How does the middle school child find the courage to follow their moral virtue guidelines? When it happens, is because as younger children, moral virtue was encouraged to develop in a healthy manner. Many values are presented to a young child to internalize. Parents are not always conscious of which values are internalized. Some values are internalized, but are internalized in some distorted fashion that can be harmful to the child in the long run. Potentially harmful ideal selves can be developed. For example, as was discussed in last month's article, some children have an ideal self that says you have to win. Once an internalized ideal self is developed, it is difficult to change it. Criticizing it usually creates resistance, since you're attacking core values -- a core definition of self. Never attack someone’s ideal self, if you want any chance of being heard! (How could you be so stupid? Don’t you have any morals? Why would you want to do that?!) When a parent or an adult can identify the ideal self in the child, however, then he/she can challenge that ideal self positively and provocatively. The trick is not to criticize it, but to challenge it in order to raise it to a higher and more sophisticated level. This is done by first affirming the most basic motivations of the ideal self.

For example, if your little boy (or girl) wants to be a Power Ranger (Hai Yah! Punch! Kick!), and as a result, has been kicking and hitting other children (Hai Yah! Punch! Kick!... Ouch!), you might not get as far as you would like if you tell him that he is wrong to behave like that. Although you are addressing the behavior, he will experience you telling him to deny a powerful motivation from his ideal self. However, if you recognize that the underlying trait that is so appealing in Power Rangers is their... Power! you can get to adjusting his behavior through addressing his motivation. Instead of attacking his desire to feel powerful, you should confirm this. After all, having power is always an appropriate goal for any person -- whether a child or an adult -- male or female. This is why children, especially boys in our society are so powerfully attracted to toys and games where they can exert or practice power and control in their lives (or imaginary lives). The issue is, however, whether or not having this power and exercising this power is done in a manner that is appropriate and does not cause harm to other people (that is, is it socially responsible?).

"You like Power Rangers don't you? Power Rangers are very powerful. That's cool. I like the Blue Power Ranger. Which one do you like? They are so strong and powerful." It is important to distinguish the underlying motivation -- the desire to have power in this case, from the behavior that is expressed. After affirming the underlying motivation (Power), then you can define more appropriate behavior that is socially acceptable for expressing this motivation. "You know Power Rangers solve a lot of problems. Did you notice that they always try to solve the problems first by talking? And, you know something else? The Power Rangers, when they practice, they are very careful not hurt each other. They only hurt the bad guys, and only if they have to. They practice having a lot of control with their fighting."

Sometimes setting a boundary about not hurting each other works just fine. Other times, however, it doesn't work effectively by itself (note -- this is not to ignore the importance of clear, firm, logical, and strict boundary setting in discipline). When setting boundaries about not hurting each other does not work, the next thing we usually try is to be stricter -- set tighter boundaries and more extreme consequences. Unfortunately, strict boundaries and aversive consequences often don't work. It may not work because it does not address the very compelling underlying motivation -- the desire to be powerful. Or, it may work to stop the behavior, and leave the child feeling impotent -- with a sense of powerlessness; and/or give the child the message that having power is inappropriate. The boundary of not to play fight may, in fact, deny the child his/her need to experience and experiment with issues around power and control. By accepting the ideal self (the desire to be powerful) but redefining it (to power with control and responsibility and boundaries), adults open the possibility of getting the real self to behave in a more appropriate manner (playing Power Rangers without hurting each other). "You can play Power Rangers, as long as you don't hurt each other. Here, you can use these pillows to be the bad guys. You can hit and kick them. But you can't hit and kick each other. If you can't play Power Rangers without hurting each other, then you cannot play it." If after this, the child is still unable to play Power Rangers without hurting other people, the parent can be clear and confident in following through with whatever appropriate consequences that have been set. The learning about the ideal self, and the real self has been presented and followed through with from the parents’ side.

In later chapters, we can discuss additional issues around setting boundaries and consequences (including the differences between consequences, punishment, rewards, and positive and negative reinforcement) along with a discussion around the Four Theories of Timeout.

Forget them!! Forget school!! Stupid teachers…stupid principal… stupid deans… They've never respected me, so to heck with them. Just when I'm starting to do better in school… just when… Well, never mind, I'm not going to hang around for them to kick around. Always on my case…always criticizing me…always making me wrong. They say they're trying to help me. Well, maybe some of them, but most of them… stupid teachers!! They're messing up all the time. I don't hear them on each others' cases. Adults stick together even if they're all wrong. I'm not sticking around for more mess. Stupid adults! Forget them. I'm outta here!!

Looking ahead to adolescents, I would like to give you another real-life example of the ideal self vs. the real self as a way to work with children. Although the focus of most of these articles will be around younger children, there are many issues that parents get away with young children that they cannot get away with teenagers. In other words, you can get away with a pattern of mistakes when children are younger, but when they become older, you will pay the price! Many of the great difficulties of raising adolescents can be precluded with effective parenting with the children are younger. Some discipline approaches that seems to "effective" with young children have harmful consequences that do not appear until they become teenagers. For example, it is often "effective" to over control and dominate a child when they are younger. You can disrespect their needs and force young children to do what you want them to do. However, when they become teenagers, the over control and domination becomes more and more intolerable, and they can become oppositional and defiant. In other words, sweet little kids don't suddenly and inexplicably turned into monstrous teenagers! Sometimes, difficult teenagers are a consequence of problematic earlier parenting. Understanding this, can lead both to more effective discipline when they are younger that is respectful of issues of control and power, and also to effective interventions even when there has been a history of (usually inadvertent) disrespectful and disempowering actions that has created a difficult teenager.

There was a very talented therapist that I supervised that worked with a teenage boy who had a fairly negative history in the school. He had been on the verge of being kicked out of school several times. His parents, to be honest, were alternately worried about him and being sick and tired of him. He had been placed in Special Education as well. His Self-Esteem was not very strong. Fortunately, because of the support he had gotten from certain caring adults including the therapist, he was beginning to feel better about himself, and to look forward to do better academically and career-wise. However, as often is the case, he still got into trouble at school sometimes. After one particular incident, the school was on the verge again of kicking him out of school altogether. He felt that it was very unfair -- he was outraged! As often happens, he was ready to quit. He felt disrespected; he didn't like being told what to do -- he especially didn't like being threatened. He was ready to say to heck with all of it, and to slam the door on high school. The standard approach would be to encourage him to stay in school, to accept responsibility for his behavior, and try to work things out with school. The standard approach would not have worked. He was too upset. He had been through all this all too many times. They were attacking this sense of Self-Esteem again. They were jerking him around!

What were the underlying issues that could be used to help him make a better choice? Adolescents, like adult, have a lot of issues about power and respect. He felt that he was being disrespected by the school. He also felt that all he could do to assert his power was to leave -- and to leave in as loud and angry a way as possible. These two underlying motivations were the keys to working with him: respect and power and control. As he complained about the school, and said that he was ready to forget it, using some principles that we had discussed in supervision, the therapist challenged him. She challenged his self-respect; she challenged his sense of power and control. She activated his ideal self by challenging his need for respect and power.

She accused him, "You're goin’ to let them play you like that? You're goin’ to let them win? That's not too smart. You get mad, walk out that door -- no matter how loud you leave -- no matter how much noise you make while you go, remember... after that, you're on the outside and your education was left behind. You quit -- they win! Those school officials win because now they got rid of you. They already have their education -- they already went to college-- they already have a career. You won't have nuthin'. They would have won -- they would have suckered you into losing your education -- into losing your future. And you think you're so sharp!? You goin’ to let them do that to you? You goin’ to let them manipulate you! Or, are you smarter than that? Who's in control here?" With this, the young man got very upset, but upset in different way. His eyes got big, his nostrils flared, he set his jaw... he practically jumped out of his chair! "No way! No way! Ain't no way, they're going to make me give up my education! I'll show them! I'm going to graduate! Ain't nobody goin’ to keep me from graduating!!"

I want to acknowledge that using the idea of "them" can be somewhat controversial. This seems to confirm his negativity toward adults, or to agree that adults, specifically school officials were against him. In his existential experience, however, they had been against him. By using " them" as a reference point that he understood, the therapist was able to get into his reality -- his sense of what was happening in the world to him. From that empathetic connection, he opened to consider what she had to say. At that time, her clinical judgment (and I concur) was that it was necessary in order to be heard. If she had taken the standard line (that he was responsible, and that the school officials would be reasonable and had his best interest in mind), he would have dismissed her like he had been dismissing all the other adults. The result of that would have been him quitting school and losing his education. She was willing to take a chance in order to save his future. If this failed, it would have made no difference -- to therapist referring to adults to as " them" would not have made him anymore or less suspicious of school officials. By violating this unspoken rule -- that all adults are supposed to back each other up no matter what, she was able to get him to stay in school, and eventually, to develop a greater trust in adults. To be quite honest, I feel that breaking such a rule in order to have a chance at saving a person's potential- to help this young man have a possibility of a future is not a hard choice.

Now that he accepted the redefinition of his ideal self -- that his ideal self could continue to demand respect and power, but would get it from staying in school rather than leaving school, the therapist was able to ask him what he was willing to do to make it happen. In other words, what was he willing to do in order to stay in school. Since he wanted to graduate (that graduating served his ideal self-definition), he became receptive to working things out so that he could stay in school. While he still resented certain limits that were placed on him, these limits which he used to consider as controlling became less important to him. It was more important to him to control his life so that he could graduate from high school. Where before any feedback on his inappropriate behaviors was perceived as an attack on his ideal self, now he was willing to get feedback on more successful ways to achieve the new ideal self that would not be controlled or manipulated. Now he was willing to adjust his real self behavior so that he could fulfill his ideal self goals. There was much more to this process than can be discussed here, but this is a real success story. As he adjusted his real self behavior, he became more and more successful academically and socially. His grades and Self-Esteem continued to grow. Then, as his Self-Esteem grew, he was able to take more and more responsibility for his behavior -- even to the point that he could be critical of his "immature behavior" when he was younger (all of a half a year ago!). Two springs ago, he graduated from high school! He is now in a community college continuing his education. So, who won? Everyone did! Caring adults were able to help a young man succeed. And, a young man was able to get his real self to live up to a more sophisticated and healthy ideal self. And, hopefully, he will carry his ideal self with him through the rest of his life and he faces more challenges.

The therapist in this situation seized upon a great opportunity and made a difference in this young man's life. These opportunities occur all during a child's life. It is up to adults to recognize them and take advantage of them.

Mine. My Teddy. NO! Mine. My Teddy. Don't touch. You can't touch. Mine. NO! My Teddy. Get your own Teddy. Mine. NO! Don't. My Teddy. My Teddy. Mine. Uh uh. NO! Go away!I don't like you no more! No more! Go home! My Teddy. NO! NO! NO!

Educators often speak about what are called " teachable moments." These are the moments in children's lives where the circumstances are such, that children become open to learning about themselves, others, and about the world in general. Their natural curiosity, their desire to solve problems, their need for stimulation, and sometimes, their anxiety, their needs, and even their fears are so powerful at these points, that they open themselves to instruction and input from their significant adults. The teenager I discussed in the previous column that was on the verge of being kicked out of school was in a teachable moment. Teachable moments occur naturally in children's exploration of and involvement in the world. Adults who are vigilant and look for these opportunities (including seeing opportunities in moments of intense stress), can have tremendous influence on a child development.

Good teachers and effective parents can also facilitate teachable moments by introducing new things into their lives; by introducing children to new experiences, or, simply, by being excited themselves. Adults, however, need to take care that during the teachable moments that the children learn things that appropriate. As opposed to learning things that are positive, adults may inadvertently facilitate learning that may be negative, or that only serve children in the short-term but not the long-term. Or, serve short-term adult needs for order and management, but inadvertently teach children principles that may be harmful for them in their lives.

A GUEST... A SPECIAL TEDDY

Consider this scenario. Your child has a friend over to play. Your child and the friend are both very excited. Everything is going well... Until the friend wants to play with your child's special teddy. Your child doesn't want to let his/her friend play with the teddy. Both of them are getting upset. This is the teachable moment -- your child is very emotionally invested in this moment, and will be receptive to your input (which, by the way, does not mean that they will like your input or agree with what you have to say!). You might say, as many parents have said, "You need to share your teddy. You invited your friend, and this means your friend gets to play with your toys. Don't be selfish." What have you taught? What has your child learned? Your child has learned a concrete rule about social etiquette-- that the guest should have certain privileges, and the host should have certain responsibilities. That the guest gets to play with your toys; and the host has to... has to... suffer!... I mean, to give it up! You have defined the ideal self with specific real self behavior. But to follow the ideal self values, does your child have to perform this particular real self behavior? You might add, "Be a good friend. That's a good boy/girl." Now you have defined the ideal self (a good friend) as someone who shares his or her toys. And, because your child does not want to share his/her teddy, they cannot be good. Unfortunately, you may have inadvertently forced your child to conclude that he/she is a bad boy/girl! And, you may have also ignored and/or also taught your child to ignore his/her own personal needs -- in this case, his/her need to have something that is personal and sacred for him/herself only. In the extreme, this can lead to self sacrificing behavior that does not take care of one's own needs -- at all; in the adult world, in the extreme this could be called co-dependence.

The parent can still promote the same type of behavior (regarding social etiquette regarding the guest), but can use this teachable moment to also build the ideal self. The parent might say, first acknowledging their child's need to have something special and private, "That is your special teddy. I know that it is special for you. It's hard for you to share it with your friend." In the previous response, the child's needs were ignored. In fact, if the child had tried to assert his/her feelings, by saying "But it's my teddy!” it would not have been surprising for the adult to say, "Don't be so selfish!” This denies the child his/her feelings, and makes it so that when he/she tries to assert his/her feelings and needs, he/she must accept a negative label. It becomes impossible for the child to achieve the ideal self standards. Not surprisingly, children often react to this sullenly, "But I don't want to!" Parents attack began, " Don't be so stubborn!” and the ideal self is denigrated again.

On the other hand, the parent might say "I know it is hard for you share your teddy with your friend. It's hard to share when is something so special that you want it for yourself. I know you want your friend to have fun. I know you want to be nice. You like being nice, don't you? If you want to be a good friend, then sharing your teddy would be a good idea. Can you share it with your friend? That would be so nice." It is clear from this that the parent still wants the child to share the toy. The difference is that having to share is not presented as an absolute rule. Instead, is presented as behavior (that the real self might do) that reflects an ideal self of a friend who wishes to be nice to their friends. This makes it possible to not share the teddy, and still consider oneself a nice person. The previous, more rigid approach precluded this possibility.

THE IDEAL SELF IS NICE -- THE REAL SELF SHARES TEDDY... MAYBE!

It is important to note that in this particular scenario, I do not necessarily feel that a child should be forced to share his/her special toy with his/her friend. You can be a good friend, a good citizen, and a socially responsible individual in the community, and have some things that are private and personal that are not to be shared with others. This definition of the ideal self includes an ideal self who also takes care of itself -- that being sensitive and responsible to others can and should balance with self-love and self-care. If at this point, the child can share his/her teddy, then great. If on the other hand, the child is not able to share his/her teddy readily, perhaps the real self can be guided to find a way where he/she can share the teddy. For example, if the friend shares his/her own special toy with your child, perhaps your child can share his/her special teddy with his/her friend; or that they play a game together with the teddy; or, the friend can play with it for a limited time; or the child possibly be given a special treat or privilege in exchange for his/her sacrifice. If your child at this point is still unable to share his/her special teddy, don't force him/her to allow an intrusion into his/her special relationship with the teddy. If you stop here (your child has refused to share), since the real self has not shared, then it is implied that the ideal self cannot be honored -- hence your child must be a bad boy/girl. To avoid this and to develop the ideal self and real self in healthy ways, the parent may ask, "Since you can't share your teddy with your friend, and I know you still want to be a good friend, what can you do for him/her that would be nice? Is there something else really special that he/she can play with that is okay for you?" This allows the child his/her feelings, encourages them to have and develop a healthy ideal self, and trains the real self in developing positive pro-social behavior-- behavior that does not have to be rigid. This approach also encourages your child to be creative in finding the real self behavior that is positive.

Realistically, as the adult, you may be required to provide suggestions (and, perhaps some boundaries too). With all this, you may still end up forcing the issue if your child is absolutely unreasonable. While this may sound contradictory, you must remember that striving for the development of the healthy ideal self never means allowing a toxic real self to operate. For example, if after inviting a friend over to play, your child refuses to that him/her play with any of the toys-- that should not be allowed. The short term selfishness in the real self may get the child all the toys to play with. It can become internalized in the ideal self. However, such behavior if it continues in the child's life will result in social sanctions against him/her. For the long-term, it is against the child's best interest to be allowed to assert truly unreasonable and negative behavior. Finding a balance between selfishness and selflessness is the key -- a difficult key.

Understanding the differences between the ideal self and the real self offers tremendous guidance into working with people of all ages. I have been able to use it in positive ways with young children, teenagers (even oppositional and defiant adolescents), parents, couples, families, schools, organizations, and businesses, including supervisors and supervisees, bosses and employees. These articles, themselves are also presenting ideal self and real self issues as we examine how to raise young children.

STILL MORE!

Significance and moral virtue were two of the four components of Self-Esteem described by Coopersmith. Last month's and this month's articles were devoted to these two components. Your children feel loved and valued by you and the other significant adults in their lives, and you are consciously and actively supporting the development of their internalized values that will make up the moral virtue that would guide them throughout the rest of their lives. However, there is still more to developing self-esteem in your children (by now, you may have figured out that there is always more!). Next, we will begin discussing the third component of Self-Esteem as described by Coopersmith- power and control, which we have begun to allude to.

"Ahhhhh!" A scream rips through the house. It's coming from the living room. "No! Stop it!" What is it now? "Ahhhhh! Stop hitting me!" You come out of the kitchen. It's Volume 54 No. 12... in the ongoing serial saga, "The Battle of the TV Remote Control," the epic struggle continues. "It's my turn! You chose last time. I hate you! Mommy! Make her stop!" “Make him stop!” What do I do? Who is right? Who is wrong? Who cares? (Not me!) They act like Rug Rats vs. Bugs Bunny is a life and death choice! If I let him have the remote control, she feels betrayed and gets sullen. If I let her have the remote control, he will say he doesn't want to be my kid anymore and throw a tantrum. If I turn off the television, they both hate me! Is he right? Is she right? Am I going crazy? Are these the joys of parenthood!? Ahhhhh! I think King Solomon would have cut the dang remote control in half!

As much as children feel loved by the significant adults in their lives and as much they hold themselves to behavior that the ideal self has designated as being moral, their Self-Esteem still requires for them to have a real sense of power and control in their lives. Often times, adults or teacher consult with me about discipline problems. Intuitively the adults realize that there are power and control issues at play. However, upon closer examination, it often becomes evident that the discipline problems are more management problems adults have with children's attempts to get power and control. Management problems are situations where a child's or children's behavior is outside of the control of the adults (which, like it or not is a lot more of the time then you think) and affects the environment in a way that is disruptive physically or emotionally to the adults or other children (in other words, they make you nuts!). Oftentimes, a child is actively seeking more power and control in his/her life and, unfortunately, does it in a manner that is disruptive to adults. Sometimes it is disruptive to the adult because the adult him/herself has issues with power and control. (And now this little character is messing with my power and control -- who does he/she think he/she is? I thought at least with my own kids, I could be the boss! Bummer!)

Are children supposed to seek power and control in their lives? Of course they are! The desire to have power control is a lifelong venture. A better education, a good job, better income -- these are all things most adults struggle for throughout their lives. And as they are successful in gaining these things, people are to able to have greater power and control in their lives -- gaining the lifestyle they desire, a nicer house, a better neighborhood, the quality of schools for the children, and so forth. Even the struggle for the nonmaterial benefits in life -- serenity, fulfillment, security, a sense of purpose, or spirituality can be seen as gaining power and control in your life, but power and control in your emotional and psychological life. In other words, as children push for power and control in their lives at home, on the playground, at school... at the grocery store and at the... oh no, Toys "R" Us!, they are developing the skills for their lifelong adult struggle for power and control. The key here for children and also for adults is whether or not in their struggle for power and control, they do it in the way that is socially responsible. In other words, are other people harmed? Are other people's rights ignored? Are other people respected? Do other people lose their power and control as they assert theirs? Are you making me crazy!? Do you eat out where you want all the time while your partner does not get to satisfy their culinary desires? Do you get a promotion while your colleagues get stiffed? Do you get to keep playing with the truck while your little brother gets... to cry in the corner? Do you honor or betray your ideal self in gaining power and control?

TODDLER TYRANTS TO PETTY TYRANTS/BOSSES TO......?

The need to take care of your power and control issues is so compelling that many people will develop an ideal self that places power and control as an absolute first priority.... no matter what the cost. A cultural attitude that promotes gathering power and control can develop that taking care of No. 1 at the expense of others is acceptable -- even desirable. In fact, being particularly vicious and cold hearted becomes something to be admired and celebrated... "Ooooooh...that was cold!" As the bad guy who falls into the pond of piranhas and is eaten alive, James Bond, Agent 007 smirks suavely and says, "Bon Appetite." A theater full of spectators laughs with admiration. A linebacker makes a tremendous hit on a receiver crossing the middle, and as the player lies unconscious on the turf, he stands over him and taunts him, "This is my house, boy! Don't you think you can come into my house!" 70,000 people in the stadium cheer, millions more watching on TV go "Oooooh!” and the linebacker gathers additional All-Pro votes. Heather Locklear on "Melrose Place" (or Joan Collins on "Dynasty", or Betty Davis) is deliciously vicious, cruel, and vindictive.... and celebrated for years with high ratings. Mike Tyson, Donald Trump, Bill Gates, and innumerable politicians keep us fascinated, at least in part, because of the power (physical, financial, or political) they seem to have. And, adults wonder how kids can be so power crazy -- so cruel, and are so attracted to violent shows and video games!

Teaching people how to "swim with sharks" encourages being the most intimidating and voracious predator with amoral and sociopathic principles. People begin perceiving the world as being split between winners and losers-- with the implicit and sometimes overt message that losers are just getting what they deserve. And, being the winner is getting what I deserve because I grabbed it first! Or, have it now! Or, can intimidate you into letting me keep it! Or, can violently keep it mine! Many people feel this way whether it is a toy, a parking space, or land or property.... Whether it was fairly gained or violently seized... Whether it was a recent acquisition or a historical, colonial, or imperialist conquest. This becomes codified in the sayings prevalent in our society: "Possession is nine tenths of the law." "The golden rule -- he who makes the rules, gets to have the gold." "Might make right." "That was then, this is now!" The parents' version of these slogans become "Because!", " Because I'm the mommy/daddy!", "...or else!", "Because I said so!" The children's versions of the slogans become "Mine!” "I don't care!” and especially, "No!!"

TOILET TRAINING BECOMES A STRUGGLE FOR POWER AND CONTROL

Power and control is such a fundamental issue with children and adults that people do seemingly unreasonable and even outrageous things to gain it -- even to gain the illusion of it. Some of you may have experienced this when toilet training your children. For those of you who have not toilet trained your children yet, play close attention! For those of you who have been through this, you may be able to gain a clarity of principles that will help in future (there will be versions of these conflicts throughout childhood and adolescence). Sometimes infants and babies experience being over controlled by their parents. Parents decide what they wear, what they eat, what time to get up, what time to go to sleep, who they can play with, what they can play with, what they can do with their bodies, and sometimes even what they are supposed to feel and think. Well-intended parents may "reason" with their child and continually force them to do things that inadvertently cause them to lose their sense of power and control. In other words, parents continue to work on them until they wear them down enough so that the kids finally just give up.... give up just to get away from the hounding. "Just this time" becomes virtually all the time. Having lost control to the parent, children will seek ways to get a sense of control back. How they do this varies from child to child and depends on many things including developmental stage and temperament. Toddlers may assert control and power over the last thing that they have -- the only thing that parents cannot manipulate or control, their pee and poop!

- You made need wear that yucky shirt. I don' like little hearts anymore -- I like ponies, not hearts!

- I like peas. I like carrots. I hate broccoli! You made me eat that nasty stuff!

- I didn't want to get up -- I was still sleepy. What's an appointment? All I know is that it's something that makes me wake-up when I don' want to.

- I don' want to nap! I don' want to nap! I hate naps! I want to play! Grrrrr! I'm not tired -- you'd be grumpy too if someone tried to make you nap when you didn't want to!

- I don' want to play with yucky Johnny. I don' like yucky Johnny! I don't care that yucky Johnny's mother is your friend. I don't like yucky Johnny!

- This is fun. Hitting the bowl with a fork makes a neat sound. Whatcha' mean? Don't play with the fork? It's fun! Hey... Give it back!

- Mmmm, that feels good.... Mmmm, real good! Mmmm! Mmmm! What? Mmmm! Don't touch? Why not? Mmmm... Because what? What's nasty?

- Auntie Judy smells funny. And, she pinches my cheeks and gives yucky kisses! And she gave me that yucky shirt with the hearts... I'm supposed to feel grateful? That's yucky... she's yucky!

- Yucky yucky yucky! I'm wrong to feel that way? That's what you meant? That's what you want? I knew what you wanted!? I knew what you meant!? You know what I was thinking!? I was thinking what!? I was trying to get away with what!? Sheesh!! Can't I do anything!? Can't I even feel what I feel... or think what I think!?

- That's it!! You make me do all that... you tell me what I feel and think... that's it! There's only two things left I have control over -- only two things you can't take away... can't control. It's my pee! It's my poop! You can't have it when you want it! You can't make me put it were you want it! It's mine! It's mine!

In mainstream American society, toilet training is usually begun somewhere around 2 1/2 to 2 3/4 years of age. Successful toilet training is usually accomplished somewhere around 2 3/4 to 3 years old or slightly older. This varies a great deal from family to family and from culture to culture within mainstream American society and cross-culturally in non-mainstream American societies and non-American communities. Generally speaking, this is the age range when children are now physically able to control their bowels and bladder; language skills have developed enough so that they are able to both understand communication from the parents and to communicate back to the parents; cognitive abilities have developed to the point that they can understand the process and the need; and, social development that supports the process has occurred (social situations where toilet training is required have become desirable -- such as preschool). Children who were toilet trained earlier than these ages, may be developmentally precocious; or, (more likely) are physically highly regular as to when they have bowel movements and urinate; or, (even more likely) they have exceptionally well trained parents! Sometimes, exceptionally well trained parents can be counted on to anticipate toileting needs and put their child on the toilet quickly and effectively enough so that it seems that the child is actually trained. In those situations is arguable about who actually has been trained! In my experiences working with young children and parents, when toilet training prior to two and a half has been "successful", it is often the result of extreme vigilance and very hard work; in other words, the vigilance and hard work is compensating for the child being marginally developmentally ready to be toilet trained. An important question here is-- Is it worth it? For some parents it is, and for many others it is not. The other important question is-- Is it worth it for the children? Or, is it stressful or even harmful to the children?

AND THE CHALLENGER IS.... AN ITTY BITTY LITTLE KID!

On the other hand, when a child's toilet training is not completed successfully (allowing for occasional accidents) by about three to three and a half years of age, it is often because there are major power and control issues between parents and children. By not doing the only thing that cannot be physically forced upon or from him/her, the child asserts control and power. Since he/her cannot control the other parts of his/her life, at least, this can be the one thing that can be controlled. And, in controlling this, the child can get some power and control at least by aggravating the parents! "Maybe I can't get candy. Maybe I can't get out of the playpen. Maybe I won't get the La La talking TeleTubby. But, I can make Mom crazy! I can. I can make Dad's veins pop out! I can.... and his eyes bug out! I can. I can make the whole family wait...and wait...and wait -- I can... I am... powerful! I am the boss! I win!" The "winning" comes, unfortunately, with major negative consequences: implicit and overt negativity from the parents that affect children's self-esteem, frustrated and increasingly intolerant parents, and many practical implications that affects their social growth.

What can parents do? Parents must first acknowledge their own issues with power and control. Imagine your itty bitty little kid in boxing shorts with humongous boxing gloves squared off against you the parent also in boxing gloves. A power struggle? How silly! And worse yet, you're losing! You're in a power struggle with a runt, and you are losing! Ridiculous! If adults find that their interactions with children become power struggles, then something is fundamentally wrong for the adults because of their own issues with power and control in their lives. Unresolved issues with power control can contaminate the parents' perspective of their children's developmentally appropriate struggles for power and control. Remember, it is said that there's nothing like becoming a parent to bring up all the emotional and psychological garbage that you had thought you had already taken care of! And, to bring it up with an intensity that had never been experienced before! However, while it is developmentally appropriate for your child to struggle for power and control, it is not developmentally appropriate for mature adults to have power struggles with children. Who said we had to be mature to have babies!? Physically mature -- sure; emotionally and psychologically mature too!? Oh my! I used to ask my community college child development class to come up with a list of 10 requirements to become a parent. The students, aged 20 to 60, most with children and some with grandchildren came up with some excellent requirements. However, when I asked the class if they as individuals had fulfilled these requirements before they had become parents, very few said that they had been "qualified". As a consequence, most of them and most of us learn to parent on the run -- an on the job training process where we help our children deal with their issues including their power and control issues while we are still dealing with our own power and control issues. If you can accept this (actually it doesn't matter whether or not you accept this -- it is still reality!), you can take responsibility for it and parent more effectively.

So children are supposed to seek power and control. Does that mean we're not supposed to discipline them? What if they are abusive? What if they are doing dangerous things? Power without sensitivity... control without responsibility is dangerous politically, socially, within the family, and for individuals. You want to raise a child with Self-Esteem -- that includes a sense of power and control, but you don't want to raise a tyrant. Setting boundaries around power and control becomes critical.