9. Recovery & Healing - RonaldMah

Ronald Mah, M.A., Ph.D.

Licensed Marriage & Family Therapist,

Consultant/Trainer/Author

Main menu:

9. Recovery & Healing

Therapist Resources > Therapy Books > SorryNotEnough- Infidelity-Cpl

Sorry is not Enough, Infidelity and Betrayal in Couples and Couple Therapy

Chapter 9: RECOVERY & HEALING

by Ronald Mah

INDIVIDUAL HISTORY AND ASSESSMENT

“The discovery of an extramarital relationship by a spouse frequently is the precipitating factor that causes a couple to enter marital therapy. This is especially true when reconciliation is the stated goal. In order for the therapist to work successfully with couples presenting themselves for treatment with this problem four or more factors must be taken into consideration. These include:

The type of extramarital relationship.The personality make up of the offending spouse.The spouses’ perceptions of the marriage and the assumptions each spouse has about his/her partner’s commitment to remaining married.Circumstances and complaints during the marriage such as alcoholism or hypoactive sexual desire” (Bagarozzi, 2008, page 1-2).

Dupree et al. (2007, page 331-33) identify within different clinical approaches to treating infidelity share seven common goals. They are

Create a safe, trusting environment for the clients to examine and explore their relationship,Provide a structured environment for the clients to feel equally validated and guided in the process of therapy,Examine the emotional, behavioral, and cognitive reactions to the trauma of infidelity,Explore past and present patterns of the relationship,Explore past and present expectations and meanings of the relationship, (f) Provide a structured process of self-disclosure to allow for understanding and a means of rebuilding attachment and trust,Examine new patterns, meanings, and expectations of the relationship on a structural, behavioral, emotional, and cognitive level in order to maintain trust, andExplore the process of forgiveness and mutual healing.

Early in treatment for infidelity in the couple or prior to starting couple therapy, the therapist needs to get individual history including family experiences. Prompting the partners for this information reveals their development and process not just for the therapist but also most critically for them. In particular, the therapist should check for affairs or other indications of infidelity in either partner’s family-of-origin and extended families. The therapist should be alert to emotional betrayals or boundary crossings in addition to sexual infidelity. For example, infidelity may be the unfaithful partner’s personal version following family-of-origin or extended family models that manifested in others as alcoholism, religious rigidity, eating disorders, workaholism, or other boundary problems, compulsivity, or addiction. Each partner’s prior experiences of intimacy in previous relationships should be investigated, including attitudes towards fidelity. The therapist should uncover the motivation of each partner to engage in therapy and/or to stay together. The ability to have empathy and willingness to forgive and/or accept the other’s regret and apologies can vary significantly. The unfaithful individual may also have limited to greater ability to accept forgiveness and/or acceptance, or be consumed with guilt and self-hatred. The therapist should find out what the offended partner of the unfaithful individual believes is the motivation for both committing infidelity and for wanting to stay in the relationship. Assumptions of the unfaithful partner’s reasons for reconciliation may be accurate and be either devastating or encouraging to the offended partner or to therapy. Conversely, the assumptions may be incorrect, give false hope, or be further emotionally destructive.

Bagarozzi (2008, page 9-10) suggests four assessment instruments: Justification for Extramarital Involvement Questionnaire (Glass & Wright, 1992), Marital Disaffection Scale (Kersten, 1988; Kayser, 1993), Trust Scale (Rempel, Holmes & Zanna, 1985), and Spousal Inventory of Desired Changes and Relationship Barriers (Bagarozzi, 1983). The therapist may use one, some, or all of these tools, other instruments, or devise some formal or informal assessment process of his or her own. The therapist prompts the individual’s justifications and rationalizations for stepping outside of the monogamous committed relationship for sex or a sexual relationship. Among the reasons are sexual explanations that the relationship sex was no longer exciting or satisfying, thus justifying seeking excitement and satisfaction breaking fidelity. Each partner can be examined more carefully regarding overall satisfaction in the relationship or marriage while looking at the degree of satisfaction in specific key areas of the relationship. “Disaffection is described as the gradual loss of an emotional attachment to one’s spouse. Disaffection includes a decline in caring about one’s spouse, emotional estrangement and an increasing sense of apathy and indifference toward one’s spouse” (Bagarozzi, 2008, page 9). The more disaffected an individual, the less willing he or she is to work on resolving the affair. Job or vocational promotions or progress are among external motivations given for sexual infidelity, as opposed for personal satisfaction. The individual may alternately claim the affair is to gratify emotional needs including for romance and intimacy needs. These and other blockages or interferences to reconciliation need to be addressed. In addition, there are barriers to separation or divorce such as financial entanglements (debt, mortgages, dependency, etc.) children, or community expectations (religious standards, family expectations, political status, etc.). In addition to each person’s perceptions, his or her assumptions of the other partner’s beliefs, views, and thinking should be checked.

Commitment to the other partner and to the relationship needs to be determined. As discussed earlier, strong commitment predicts greater investment in therapy and greater hope for positive resolution, while weak or tentative commitment becomes an initial critical focus of the therapy. Low commitment will diminish investment and work at resolving the infidelity. Each partner’s commitment is influenced by how much he or she perceived the other partner’s level of commitment. At the same time, the therapist begins to gain a sense of how much each partner trusts or mistrusts the words of the other. The therapist should look at “three areas of interpersonal trust: faith in one’s partner, predictability of a partner’s behavior and actions, and dependability. This last dimension, dependability, deals specifically with sexual fidelity” (Bagarozzi, 2008, page 10). If such issues are not addressed therapeutically, the subsequent process for healing the relationship becomes less likely to be successful. Consideration of various indicators or assessments would lead the therapist to some preliminary conclusions. Each partner sees him or herself somewhere between being entirely voluntarily to completely stuck in the relationship. And, sees the other partner seeing him or herself in some stage of being volitional or imprisoned in the relationship.

“Once assessments and diagnostic formulations have been completed, the therapist will be able to make a well-informed determination about the course of therapy. In some cases, group and individually focused treatments may prove to be valuable adjuncts to marital therapy. This is especially true when the sexual behavior of the offending spouse is judged to be compulsive or is thought to be symptomatic of a personality disorder or paraphilia. Since the prognosis for successfully treating certain types of personality disorders (e.g., narcissistic, borderline, paranoid, and anti-social) and paraphilias is poor, a frank and straightforward discussion with the couple about the nature of these conditions is recommended. How the therapist approaches such issues is a matter of personal style, and care should be taken not to present an overly pessimistic picture” (Bagarozzi, 2008, page 10). Baucom et al, (2008, page 379) recommends that, “After completing the assessment, the therapist should have a good understanding of how the couple is functioning. The therapist should then provide the couple with (1) the therapists initial conceptualization of what may have led up to the affair, (2) a summary of what problems the couple is currently facing in their relationship and why they are experiencing these problems, and (3) a treatment strategy. Then the couple should be given an explanation of the stages of the recovery process and the response to trauma conceptualization described in the introduction.”

THERAPIST CONFIDENCE

The therapist may have concerns about being this assertive in presenting a therapeutic road map to recovery and healing. The definitiveness of the presentation may in fact be essential to dealing with infidelity. The partners have found themselves, and especially the offended partner has found him or herself at a destination that they had not anticipated or planned for. Their minds may be frantically searching for clues and cues for how they strayed off their relationship path. They are often desperately confused about what happened. At this point, “if both partners are not given some reassurance or hope that recovery is possible, the relationship will be volatile and increasingly susceptible to dissolution. This vulnerability mandates that the therapist have a sense of what direction to take a couple, especially when so many issues can challenge progress in any particular direction. It is imperative that the clinician have a theory that clarifies where the relationship must go if it is to survive the attachment rupture” (Reid and Woolley, 2006, page 224). “In regards to the therapist’s role, nearly all the models describe a therapist who is direct, active, advice-giving, collaborative, and flexible” (Dupree et al., 2007, page 333). The confidence of the therapist presenting his or her summation of infidelity’s development, identifying problems to deal with, and how the partners are to deal with it may be vital to boost the marginal hope the partners tenuously hold. The therapist may work from a variety of potential therapeutic orientations and strategies. He or she should describe how recovery and healing proceeds and how therapy will facilitate the process based on direction indicated by assessment.

The offended partner is invited by the therapist to articulate the injury and the impact it has had. This injured partner is encouraged to begin risking reconnecting with his partner (now accessible to him or her through couple therapy). Generally, the offended partner recounts the emotional pain associated with the sexual behavior. In describing his or her experience, the offended partner might share feelings of abandonment or helplessness or times when he or she experienced a violation of trust that damaged his or her belief in the relationship as a secure bond. Often, the offended partner speaks about this injury in an emotionally reactive manner. Through this account, the injury becomes alive and present rather than a distant or disconnected recollection. The unfaithful partner might discount, deny, or minimize the incident. This trivializes his or her partner’s pain. The unfaithful partner subsequently can become defensive as a way of protecting a fragile sense of self. In some cases, the defensiveness is a manifestation of narcissism desperately trying to protect the broken sense of self.

The offended partner begins to integrate the narrative (the story or context in which the events occurred) and the emotions associated with the story. This process accesses the attachment fears associated with the injury. The therapist helps the offended partner remain connected with the pain of the injury and begin to articulate its impact and significance with respect to attachment-related emotions. At this point the identification and expression of painful emotions often elicits new emotions. Anger is translated into clear expressions of hurt, helplessness, fear, and shame. The connection of the injury to negative patterns in the relationship becomes clearer. For example, the offended partner says, “I feel so hopeless. I find myself yelling at him to show him he can’t pretend I’m not here. He can’t just wipe out my hurt like that. I want him to suffer too.”

The unfaithful partner develops understanding of the significance of his or her behavior and acknowledges the offended partner’s emotional pain and suffering. The unfaithful partner, supported by the therapist, begins to hear and understand the impact of his or her sexual activities in the context of attachment. The therapist leads the unfaithful partner to reframe the pain of the offended partner as a reflection of his or her love for the unfaithful partner. The unfaithful partner needs to realize that suffering exists because the offended partner considers him or her a person of importance. The ability to give an alternative explanation to the offended partner’s emotional pain empowers the unfaithful individual to let go of beliefs that the protests are personal attacks or a reflection of his or her own inadequacies. The unfaithful partner is invited to continue exploring the offended partner’s pain and suffering and elaborate on how the behavior evolved for him or her.

The offended partner moves toward a more integrated articulation of the injury and how it relates to his or her attachment bond. He or she expresses the grief and loss involved with the injury and any fears that may exist about the attachment bond (e.g., fears of abandonment, being alone, not being loved, or future betrayal and ruptures of trust). The offended partner, in the safety of the therapist’s office, allows the unfaithful partner to witness his or her vulnerability. The unfaithful partner acknowledges responsibility and empathetically engages in the process of healing the relationship. The unfaithful partner becomes more emotionally available as he or she assumes accountability for his or her part in the attachment injury. Expressions of empathy, regret, and remorse may be present. The offended partner is invited to express his or her emotional needs (e.g., “I need reassurance,” “I need to feel loved,” or “I need to feel safe”). He or she may risk by asking for reparative comfort and caring, which were unavailable and inaccessible at the time of the attachment injury.

If the unfaithful partner is able to demonstrate the ability to meet the emotional need of the offended partner, a bonding event occurs. The bonding creates an antidote to the hurt created by the traumatic experiences associated with the injuring behavior. Beliefs about the relationship are redefined (e.g., the relationship can be a safe place), and the couple collaboratively reconstructs a new narrative of the traumatic events. This narrative has order and may include, for the offended partner, clarity about how the infidelity developed and why his or her partner made choices that undermined the foundation of their attachment. For the unfaithful partner, he or she may reconstruct beliefs about his or her way of coping with stress or emotional pain. The unfaithful partner reorganizes his or her beliefs about the attachment being a safe place where his or her needs can be met.

The therapist should be well aware of virtually inevitable derivation from a specific plan as is therapeutically necessary. Partners may need to be seen individually at times. There may be personality disorder traits that demand attention. The unfaithful partner may re-engage the affair partner sexually or have another one-night stand. Other acting out or self-medicating with alcohol, substances, or behaviorally may intrude upon the relationship. Nevertheless, someone has to know what has happened, what is happening, and what to do to make the relationship work again. The offended partner and the unfaithful partner need the therapist to be that confident guide. An affair and the couple with infidelity are indicative of poor boundaries. The therapist who presents vague or overly flexible or undefined boundaries in a therapeutic process risk further aggravating the partners’ boundary anxieties. “When a couple feels out of control and in crisis, providing healthy boundaries can help to create some sense of normality and predictability. Because their own relationship has become dysregulated, the therapists guiding the couple in setting boundaries or limits on how the partners interact with each other can be helpful. The injured partner often is greatly distressed about the outside person who had an affair with the participating partner. This intrusion of a third party into their lives is a major factor creating anxiety and a lack of safety. Therefore, setting strong and clear boundaries on interactions with the outside, third person is very important” (Baucom, 2006, page 379).

The therapist holds certain key goals as essential to recovery and healing. These can be shared with the partners as the goals and process of therapy and their relationship growth and change. Reid and Woolley (2006, page 231) identify important issues for healing attachment rupture that can be used as goals of therapy and of the couple’s process.

The hypersexual partner needs to develop the ability to regulate and process his own feelings and respond to his partner’s emotional needs.Core maladaptive beliefs about self and partner need to be transformed to healthy adaptive beliefs.A road map for restoring trust needs to be established.The injured partner needs to feel that her partner understands the impact of his choices to engage in hypersexual behavior.The couple needs to have some experiential evidence that they will not regret their decision to recommit to the relationship.Forgiveness for unhealthy choices needs to occur.Both partners need to reorganize their feelings and beliefs about their sexual relationship.New patterns and rituals for accessing, connecting, and responding to each partner’s emotional and physical needs must be established.

As the therapy progresses, the therapist will identify goals within goals that need more direct and concentrated attention. For example, the first issue or goal to help the unfaithful partner regulate and process his or her own feelings may run into significant developmental issues including childhood trauma or personality disorders. There may be conflicting cross-cultural standards for the unfaithful partner based on gender or social models that need to be addressed. There may be negatively complementary or complex cross-cultural standards for the offended partner to express and accept responses. Also maladaptive core beliefs may be deeply embedded and hold convoluted psychological landmines that need to be defused. And so on and so forth since the other goals may uncover other vital influential issues.

THERAPY FROM CLINICAL JUDGMENT

The partners may ask the therapist directly if they can recover and heal from the affair. There are key elements that predict greater likelihood of reconciliation. An important “sign of salvageability lies in how much responsibility the unfaithful partner takes for the choice they made, regardless of problems that preexisted in the marriage… If the unfaithful partner says, ‘You made me do it,’ that's not as predictive of a good outcome as when the partner says, ‘We should have gone to counseling to deal with the problems before this happened’” (Glass, 1998, page 74). Other elements are empathy and understanding about the vulnerabilities to infidelity in the relationship. The therapist may find that the unfaithful partner has difficulty or resists empathizing with the offended partner’s pain, taking responsibility and blames the other partner for him or her seeking “attention” elsewhere. Unwillingness to seek insight about what lead to the affair decreases probability of recovery and healing. Given that these elements tend to be productive, the thrust of therapy would push for the unfaithful partner finding empathy, taking responsibility, and understanding individual and mutual vulnerabilities in the relationship. The therapist may conduct therapy towards these goals by following a prescriptive process as presented by various therapists and theorists. However, since each affair, the unfaithful partner and offended partner, and the affair context consist of a variety of nuances, similarities, and differences, the therapist may be more successful working from conceptual principles directed by ongoing in-session assessment. The therapist will need to accentuate or de-emphasize certain issues, factors, strategies, and interventions based on clinical judgment.

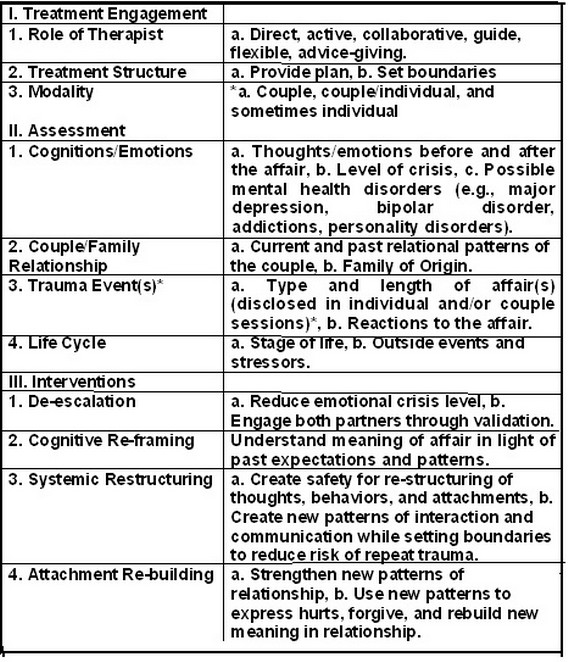

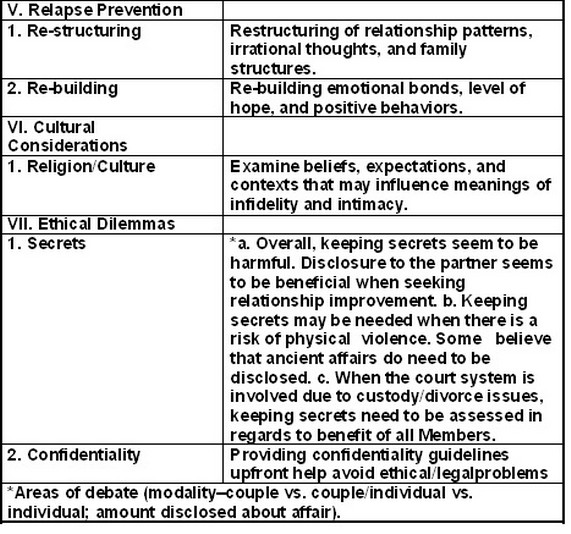

Dupree makes suggestions on therapeutic themes from therapist relationship assessment to treatment interventions and issues that may be useful in working with a couple dealing with infidelity. Certain strategies may be applicable to most couples, while a cognitive approach may be useful to a particular set of partners. Systemic or attachment approaches may be applied instead or in some judicious complementary fashion based on the therapist’s assessment of the process. Other orientations may also prove beneficial for the couple. The therapist needs to have the diagnostic and therapeutic awareness to consider various conceptual orientations. The theory and resultant therapy should fit the partners rather than trying to fit the couple into a theory.

TABLE 1 Themes in Clinical Guidelines for Treating Infidelity, (DuPree et al., 2007, page 332).

Therapy may emphasize developing behavioral skills such as communication and problem-solving to improve relationship dynamics. Communication may be about the feelings, anxiety, and ambiguity about the infidelity itself and/or the overall relationship. Specific problematic interactions are then targeted for attention and the couple experiments for the most effective and efficient adaptations or changes. Any behavior related to the affair is addressed to make the relationship more fulfilling. The therapist may alternately or work simultaneously on increasing emotional connections. Emotional needs are viewed from the perspective of vulnerabilities that are mishandled between partners. Attempts to gain emotional acceptance are frustrated because of poor expressive and receptive communications. The behavioral responses are examined for practical and emotional relevance and impact. Ineffective frustrating interactions are deconstructed to show how they drive the partners apart, creating a polarizing effect. Rather than improving intimacy and connection, they made things worse.

The therapist needs to make a clinical judgment whether to focus on behavior change, emotional issues, or some other issue. The partners may not be able to follow through on behavior changes or find them superficial and unsatisfying if there is still too much anger and resentment. The partners may need to experience emotional softening towards each other for behavioral direction to be possible. Partners are guided to better identification and recognition of emotional requests and how to make effective emotional responses that meet the partner’s needs. Emotional differences may not be easily resolved, so partners need to be guided and encouraged to be attentive, nurturing, and accepting of vulnerabilities. Partners learn behavior that validates feelings, despite having differences in feeling and interpreting experiences. The therapist works with each partner to reveal his or her emotional vulnerabilities. As he or she exposes and tries to convey difficult and sensitive feelings, the therapist attempts to facilitate the other partner’s empathy. The partners may have had negative developmental models about expressing vulnerabilities, and experienced ones vulnerabilities dismissed, exploited, excoriated, or humiliated. Along with unsuccessful and painful between them, being vulnerable to each other may have become verboten. Clumsy emotional communication may have precluded partners risking showing vulnerability to give either partner the opportunity to have empathy. The therapist manages and guides the vulnerability and empathy process- emotional softening in session as practice for interactions at home.

The offended partner may feel deep betrayal, painful wounds, and fear. At the same time, the offended partner will find his or her fundamental assumptions about self identity and the relationship deeply challenged. Profound injuries become attachment injuries that require redefining the relationship not only in the present and for the future, but also from early in the partners’ life experiences. Attachment injuries violate the sanctity and serenity of heretofore, secure relationships where one has allowed him or herself to give up vigilance and become vulnerable. Attachment injuries also arise when the contract of the relationship to step up at times of crisis and need is betrayed. “In many ways, they are relational traumas that come alive when people are asked to risk engaging and being vulnerable, and they consequently block couples from reengaging. There comes a time in the therapy process where attachment injuries must be addressed in order for the relationship to move forward on the path to healing” (Reid and Woolley, 2006, page 227. Developing boundaries and mechanisms for a safer faithful relationship may not be possible without also working through ancient from formative relationships and re-triggered attachment wounds from infidelity.

Since the emotional intensity of dealing with infidelity can be overwhelming, the therapist may also help the partners examine their relationship and dynamics from a third-person perspective. “During unified detachment, the therapist helps the couple step back from the problem and assume a more descriptive and less evaluative stance toward the problem. For example, the therapist may engage the couple in an effort to describe (without evaluating) the common sequence that they go through, to specify the triggers that activate each other and escalate negative emotions, to create a name for their problematic pattern, and to consider variations in their interaction pattern and factors that might account for these variations” (Baucom et al, 2006, page 386). This more dispassionate discussion can help the partners note their interactions while refraining from accusations and blaming. The therapist is often active pointing out beneficial choices versus negative choices in the partners’ interactions. The therapist prompts each partner what choice he or she made and to consider what alternative choices might have been more productive. The partners can tell each other what provokes negative feelings and responses that should be avoided. They also identify what triggers positive feelings and responses that should be maximized. As emotional reactivity lowers and the partners develop more self-awareness and skills, they can activate and engage in unified detachment with minimal assistance and eventually, on their own especially at home. The partners experience that a more effective productive and mutually advantageous interaction is possible.

Therapy becomes practice for the partners. It is guided and supervised practice with the therapist intervening as needed. Practice continues throughout therapy and interactions at home. These practice experiences are critical to recovery and healing. They serve to create new bonding experiences and growth of trust and security. Re-experiencing of emotions and processes with support and intervention helps break negative behavior cycles between the partners. They are essential reparative experiences needed to counter-balance the destructive experiences from infidelity and create new connections. The partners have often been traumatized by the painful failure of their interactions and have devolved to the point where they avoid or rarely engage each other over sensitive issues. Therapy purposely prompts the partners to interact over these potentially explosive hurts, betrayals, and resentments. When the therapist is able to sufficiently manage the interactions so that they are not too painful, not overwhelming emotionally, and do not trigger destructive consequences, the partners become less fearful of re-engaging. They become comfortable enough with discomfort. They find themselves to be resilient and strong enough, and able to recover sufficiently without too much effort eventually. The partners can increasingly tolerate the risk, the emotions, and aftermath. Difficult sensational risky interactions have become manageable. There develops a mutually reciprocal growth process between dealing with issues becoming safe enough and the partners becoming strong and skillful enough. The issues become more identifiable as unproductive patterns that can be interrupted. The partners are less negatively sensitized to the issues. They take ineffective and clumsy communications and behaviors less personally. They are more likely to ascribe or at least give the benefit of a doubt that poor communication is due to a lack of skills rather than intended insult or disrespect. Improving overall tolerance lessons the emotional reactivity that sabotages further exchange that facilitates recovery and healing.