Discip chapters 16-19 - RonaldMah

Ronald Mah, M.A., Ph.D.

Licensed Marriage & Family Therapist,

Consultant/Trainer/Author

Main menu:

Discip chapters 16-19

for Parents & Educators > Articles > Discipline Series

Chapter 16: SIMPLE QUESTIONS TO ASK ABOUT YOUR CHILD, How They Guide You to Help Your Child

My kid... he kinda does this thing. He doesn't do it all the time, but it's something that I have noticed. I think it's something that he's done for a long time. I see other kids doing stuff like this too, but not as often... not quite the same. Is it something that he might... that he'll grow out of? I didn't think it was such a big deal, but his teacher mentioned it to me. I guess I'm asking now, because his preschool teacher mentioned it to me too a few years ago. And my mother-in-law said something about knowing another kid who was kinda the same. And then had some kind of problems later on. It really doesn't seem that bad. Do you think it is OK that he does this? Is this something I should be worried about? Is there something I should do... that I can do?

Many times when I work with parents or teachers, they present with a lot of anxiety about whether or not there child has a serious problem or not. Sometimes, it's clear that there is a problem. However, often the adults are not clear whether it is a problem that can be readily handled, will pass naturally, or is something substantial and potentially dangerous. There is a simple set of six questions that I often use to begin the assessment and diagnosis process. Many times, the answers to these questions bring great relief to the adults. Other times, the questions allow them to have a focus that will improve successful interventions to help the child. The questions are asked approximately in this form, "Is this a(n) _____________ child?"

IS THIS AN ANGRY CHILD?

Some children and some adults are angry people. They carry in their bodies, their facial expressions, in their attitudes, values, beliefs, and in their behaviors consistent anger. Or, the anger lies shallowly beneath the surface. The anger can come from historical grievances, current hurts or stress, and often, from perceived attacks or slights. Small things that could be or would be perceived as inconsequential by others are held on to for days, weeks, months, and even years -- held on to forever. When I work with couples, one or the other may mention an issue, or there has been distress or hurt. Interestingly, a member or both members of the couple may claim that he or she has just accepted it and moved on. Sometimes, they have moved on because they have processed the issue, reconciled it, come to some resolution, and as such, have a greater intimacy and understanding between them. However, many times the issue has not been completely processed, not been reconciled, has not reached mutually satisfactory resolution, and there is now less intimacy and understanding between the couple. Yet, they may still claim that they have accepted it and moved on. In such cases, I sometimes use the metaphor that they have taken the issue and squeezed it and crushed it into a small hard nugget of bitterness that they dropped onto the pile -- the pile of resentment. This pile of resentment often becomes the Mount Bitterness that blocks the transmission of nurturing and intimacy. It is often a mountain that is actually volcanic and likely to explode at any given time. It is often clear to others, that the bitterness and the anger lie active beneath the surface.

Is your child, an angry child? The anger may manifest itself in temper tantrums, a hypersensitivity, and a hypervigilance. Or, it may express in a seething mood -- a sullen attitude toward everyone and everything. This is not the same as the common reality that your child can get and does get angry at times. Everyone gets angry at times. Everyone has experiences in situations where getting angry is the most natural thing for them to do. It is also important to remember that anger is a normal, healthy, and positive energy, if properly expressed. Anger enpowers us to take the risks that we would otherwise be too fearful to consider. Anger gives us the energy to challenge the things that need to be challenged in order to have a healthy and secure life. Anger feeds the righteousness that enables one to take care of oneself. How often have you been shortchanged by some store or been dismissed by someone, and then use anger to energize yourself to confront your potential adversary? "You see this!? They overcharged me again! What's wrong with them? I'm tired of this mess! I'm going back to the store and get my money back!" Why would someone bother to go through all these emotional shenanigans in order just to get a few bucks back? What is so daunting about getting a simple error corrected? What is intimidating is that the other person or the institution may be insulting, dismissive, or even humiliating to you as you approach them. Confrontation has danger for many people. Sometimes, the danger has been very real in their life experiences whether in the family or in certain communities or historical experiences. Other times, there is not physical danger but an emotional or psychological danger. Anger often gives us the energy to confront this danger in order to have justice or security. This is also why you should never tell someone, "Don't be so angry! I don't see why you are so angry!" In saying that, you're disabling them from the energy that allows them to take care of themselves. What is more appropriate, is to acknowledge the anger coming from some righteous existential place, while also challenging, guiding, or shaping the actions and behavior the anger initiates. Is this an angry child? This question refers to the ongoing and enduring -- more times than not, with or without provocation angry mood which becomes an angry personality. If the answer is yes, then there is a greater level of concern.

It is important to remember that anger is normally not the primary emotion. Anger is normally the secondary emotion. Before there is anger, there is an underlying emotion -- and emotion that asks for an action of self-preservation, increased security, and nurturing. In other words, before the powerful active secondary emotion of anger, there is often a primary vulnerable emotion. Anger, however often ignites behavior that can be highly problematic and destructive for individuals and the community. Such behavior of striking out and of hurting self, others, and the community process and property is so sensational, that it automatically draws the attention and discipline of other people (including the authorities to adult transgressions, and of adults to children’s misbehavior). People are usually aware that the behavior has a precedent in the anger of the transgressors. However, they often forget that the anger also has a precedent. Boys and men are particularly vulnerable to this misdiagnosis and to a cultural socialization process that disallows them and disconnects them from their vulnerable feelings. This is exemplified in the classic plot of every so-called "action flick" over the last several decades. In the first ten, fifteen, or at most twenty minutes of the action or guy movie, the hero's mother, father, brother, sister, wife, girlfriend, best friend, old friend from childhood, child, teacher, captain, childhood mentor, teammate... or all or some combination of the above are massacred by some criminal, henchmen of some corporate despot, or terrorist. As he holds his dying (fill in the blank), he despairs with tremendous anguish -- tears streaming down his face. His (fill in the blank) dies. The finality of the death hits him and his despair intensifies -- for about another 30 seconds! Then he turns his head up and although the tears are still fresh on his face, his jaw sets and his eyes turn hard. And the rest of the movie is cold anger and KILL KILL KILL!! Such a movie plot is an expression both of anger being normally a secondary emotion, and of cultural male training that any of the sensitive and vulnerable feelings are not to be expressed (love can be -- sometimes!) and when they do arise, they are to be expressed through anger, or anger is expressed in their place.

If the answer is "Yes, I have an angry child," then you must do two things: first, find the emotion or issue underneath the anger, and second, teach the child how to express that anger in appropriate and healthy manners.

IS THIS A SAD CHILD?

Some people, including children carry a heaviness in their heart as they move through the day... as they move through their lives. Normally, when we think about someone being sad or depressed, we consider two very different manifestations of that. The first is the normal sadness or disappointment that occurs in life when one is disappointed, disempowered, dismissed, disrespected, devalued, insulted or impugned, or frustrated by others' actions or by one's own behavior. This sadness or depression is transitory. It is an immediate consequence of circumstances in the immediate experience: a friend who away on a trip, losing a promotion, finding oneself in debt... stepping on the bathroom scale! However, in the larger schemes of life and of living and relationships, there are multiple other messages and interactions that are fulfilling. This sadness or depression passes as the rest of life that is relatively fulfilling, rewarding, and meaningful, reasserts itself -- or as a one reasserts him/herself in life. This is not what this question asks. The other major perspective that people come to when they think of depression is of Major Depression, which is a clinical diagnosis. When someone has Major Depression, he or she is virtually nonfunctional in life. The depression is so pervasive that such a person is often unable to make even the simplest decisions in life, to maintain basic self-care habits, to work, to interact with other people, and sometimes, to even just get out of bed. Profound feelings of low self-esteem, self-hatred, helplessness and hopelessness and often a deep sense of humiliation for having such negative feelings can move such afflicted individual towards suicidal thinking and suicide.

Normally, the question "Is this a sad child?" does not refer to either normal sadness or clinical Major Depression. One hopes that the severity of symptoms of Major Depression would be readily recognized and action to intervene activated. There is, however, another level of sadness or depression that can be likened to being the "walking dead." Or, moving through life with a 50 pound weight on your back that fluctuates ounce by ounce on a day-to-day basis. It becomes a weight that bears down on your life -- sometimes, gradually intensifying and exhausting you. The clinical term for this type of depression is Dysthymic Disorder. An individual with this issue is largely functional in life -- he or she gets up, takes care of personal hygiene, gets him/herself to school or work, and has relationships. And, "progresses" through school, career, and life. However, the progress or accomplishments ring hollow, as there is no sense of growth or achievement. Such a person may or may not act out or show behavior that makes other people notice or even think that they are depressed. Adults often function for decades in this mode. There is usually some significant and enduring dysfunction in the family or experience of trauma that is the source of the ongoing dread or sadness: a mentally ill parent, an alcoholic family member, physically present but emotionally disconnected parents, ongoing or historical emotional if not physical or sexual abuse, victimization, excessive stress, profound emotional loss, unfulfilling relationships, secret pain, and so forth. In adults, the low level of depression may not be noticeable because of the person otherwise functioning in life (although, with subdued mood or hidden sadness). In children, it is often much more difficult to recognize this kind of depression. Children will sometimes express depression in the same classic ways as adults do: lethargy, appetite changes, hopelessness, negative thinking, isolation, and so forth. However, children will also express depression in all sorts of additional manners. They may act out, lose toilet training, change eating habits, become obsessive, become unmotivated in school and other activities, hyperfocus on school and other activities... in other words, just about any change in behavior can be an indication of depression. Some children have such enduring (but low level -- without severe acting out) negative experiences from so early in their lives that they do not know anything else. Many of these kids are time bombs of depression that explode when they reach adolescence. Others pass through adolescence and continue their low level of depression decades into their adult life. It is important to remember that just because a child or person does not present an obvious crisis to others, that does not necessarily mean that everything is OK. People in children are not normally just sad; there are usually reasons why they are sad. While there are people who do benefit quite a bit from antidepressant medication, with any examination of their life history and experiences, one will find reasons for them to be and to have become depressed. If the answer is "Yes, this is a sad child," then his or her adults need find out why this child is sad. And then, to work toward addressing those issues.

IS THIS AN ANXIOUS OR FEARFUL CHILD?

An anxious child or person may or may not be a fearful person as well. When someone has a fear, however, it is a specific thing, situation or experience, or person that is feared. In some ways, it is relatively simple to deal with. If your child is afraid of snakes, then there are two relatively simple approaches to dealing with the fear. One is to avoid snakes! No snakes -- no fear! No fear -- no problem! Two, is to facilitate a systematic desensitization to snakes. Simply put, this means to gradually expose oneself more and more to snakes in a matter where one maintains control of exactly how much exposure he or she chooses to experience. In doing this, the person can gradually experience his or her fear and gradually experience his or her ability to handle the fear successfully. Over time, he or she will gradually challenge the fear with greater and greater exposure until the fear has been eliminated... or has reached a manageable level.

The natural tendency for most people -- much less children, is to avoid their fear. However, in avoiding your fear, often the fear becomes more and more intense and more and more overwhelming and intimidating. Such a fear can dominate and overwhelm life. If you have a fearful child, you need to determine if the fear is imagined or a product of inexperience, or if it has a basis in reality. If the fear is imagined or a product of inexperience, then the process of systematic desensitization would be advised. However, if the fear it has a basis in reality because, for example, there is a bully on the playground, or a tyrannical adult, or a punitive and humiliating social dynamic (including racism, sexism, classism, etc), then the child needs the adult to help him or her address the threat. Often, the reason or source the fear is not something the child can handle him or herself. The help that the child needs is often more than just advice. Often, the child needs the action of the adult. On my web site (www.RonaldMah.com) in the section on articles is a series on self-esteem, which includes several articles addressing the victim and bully dynamic.

An anxious child or person is different from a fearful child or person. While a fearful child or person has something specific that is the source or object of their fear, an anxious child or person does not have a specific source or object for their anxiety. Anxiety is amorphous and undifferentiated. It is fear without direction and as a consequence, fear that has no remedy. Everyone has experiences of anxiety that causes one distress. However, the anxiety tends to be more momentary or confined to a time period as one ponders and tries to anticipate possible and probable, foreseeable and unforeseeable challenges or difficulties as a task or an experience is to encountered. Anxiety about a first date. “Do I look OK? Should I wear that other top? Will I know what to say? What if we don't have any common interests?” Anxiety that one might forget a part of his or her speech -- which part one doesn't know! Or, someone might be bored! Anxiety that you might get brain freeze during a final exam -- when? And which part of the test? You don't know! Anxiety that you won't like kindergarten -- which aspect of kindergarten? Don't know! Just might. Anxiety is connected to the survival instinct. To be aware -- to be sensitive and to be vigilant just in case there may be some danger ahead. The flight or fight response to danger has a multitude of physiological consequences: various hormones that give greater energy, numb the body to sensation, increase blood pressure, and redirect blood flow to the larger muscles for battle or for running. These physiological changes serve the immediate task at hand -- to survive. The question of "Is this an anxious child?" does not refer to this normal and occasional anxiety. Children want to survive -- want to have fun, want to get to do things and have things, and as such, may have some anxiety. However, some children and adults stay in a constant state of anxiety. This is dangerous because when the body stays in a constant state of anxiety or stress – stays in the flight or fight mode, these physiological changes can wear the body down. In adults, it has been referred to as the Type A personality. Type A personalities have a multitude of physical problems as well as a propensity for emotional and psychological problems.

Some children and adults are naturally more sensitive than others. As babies, they may have been more sensitive to light, noise and activity. Such individuals are more vulnerable to becoming anxious people. However, the anxious child or person is not just sensitive and vigilant, he or she is hypersensitive and hypervigilant. The hypersensitivity and hypervigilance comes from a greater sense of vulnerability to a chaotic and unpredictable life. Someone who is strong, powerful, able to handle the challenges of life, and with ample support and protection from their caregivers will tend not to need to be as sensitive and as vigilant as someone who is weaker and less adequately supported and protected. It is important to note that caregivers can be over vigilant and overprotect as well, which can create a hypersensitivity and hypervigilance in the child. This is also addressed in my articles about the victim-bully dynamic in the series on self-esteem. An anxious child needs to be supported and protected, but also to be promoted to find his or her strength, capacities, skills, and resources to handle various challenges. Parents of anxious children also need to take a careful look at themselves and the family to see whether or not there are dynamics and behaviors that create the need for the child to be hypersensitive and hypervigilant. In other words, is there instability, distress, unpredictable and arbitrary discipline, or other threatening and intimidating dynamics in the family that would cause the child to feel vulnerable and to become anxious. If there is, there is not only a need to help and support the child, but also a need to address the fundamental health of the family dynamic.

IS THIS A CHILD WHO IS HOLDING PAIN OR LOSS?

People can experience devastating losses and great pain in the passage of ordinary life experiences. Sometimes the losses are expected -- the passing away of the beloved grandmother or grandfather; moving from a house, neighborhood, school, and community; a friend who moves away. Sometimes the losses are unexpected -- a young life loss in a car accident, a financial crisis, a discovery of a medical disability. Losses can be physical, such as a person; or it can be symbolic, such as a loss of a dream. People suffer pain when they have losses, but some people suffer in silence and alone. The grief/loss process is described using the pneumonic, DABDA. The first D stands for Denial. People often deny the intensity or even the existence of pain because it is intolerable. After an initial period of denial, people often move into the next stage represented by the letter A, of Anger -- anger that the loss has been suffered, anger for being abandoned or anger at the world for allowing this to happen. Following anger next comes B, which stands for Bargaining, which occurs when people try to negotiate the severity of the loss and pain. In an attempt to relieve the intensity, people try to look on the "bright side" -- Grandpa had a long life, we're still healthy, there still is a chance for gain, etc. Unfortunate, bargaining usually doesn't work for long as people come to the reality that the loss is not only real, but also final. Then they move into the second D of DABDA, Depression. The depression can be very difficult to endure but it is necessary to be experienced and processed in order to get to the final stage of the grief/loss process -- the second A, which stands for Acceptance. When people reach the stage of acceptance, the loss and the pain has not gone away, however the loss and the pain has been processed to the point where it has a place -- a stable healthy place in the people's life, heart, and spirit. As such people reflect upon their losses, there is a sadness but not a biting debilitating grief. With healing, there is a reflective warmth and appreciation of the place the person, experience, or dream had in their lives.

Individuals who do not, have not, or do not allow themselves -- or have not been allowed to go through the process of grief/loss, will often find themselves stuck in their pain. Some adults have held unprocessed loss for decades that caused them to live their lives in emotional and psychological pain. Children sometimes do not know how to process their losses and pain. They need to be supported to express their losses and pain. Sometimes, children will refrain from dealing with their pain -- even hiding it, because they feel it is not allowed to happen. This can be an overt command from adults to "suck it up," "be tough," or "don't be a baby about it," or, it could be from following the model of adults who deny their own pain and losses. There are many cultural variations on how losses are processed. Some allow for more overt grieving, while others have more symbolic or ritualistic expressions of grieving. Sometimes children follow the cultural model presented by their parents without understanding the deeper meanings and also, alternative expressions of grieving. Children need to be given permission to acknowledge that they have losses and pain before they can begin to grieve their losses and process their pain. Often, parents of children need to get themselves that same permission so that their children can have the permission as well.

IS THIS AN "OFF" CHILD?

This is the most sensitive and the most threatening version of the questions. Every person, especially every adult has had experiences and interactions with many many other people. They have had experiences and interactions in a huge multitude of circumstances and situations with those thousands of other people. Although, most people are not educated, trained, or experienced enough to diagnose certain cognitive, physical, neurological, educational, emotional, vocational, and other specialized challenges, just about everyone has more than ample experience with the range of "normal" behavior. From this instinct about the range of normal behavior, comes an instinct and recognition when behavior is outside of the experienced range. Usually, people will not be able to name what the issue might be or even be able to identify specifically what is unusual or different, but they can note that something is "off" about someone's behavior. It might be how someone holds their body, their gait when they walk, a look on their face or in their eyes, an unusual association of words or thoughts, a consistent inconsistency, difficulty doing something that shouldn't be difficult, an inability to retain or learn something, a developmental inconsistency, unexpected strength countered by unexpected weakness in some area, odd reactions, and so forth.

When something "off" is noticed and is repeated or replicated over time, it does not mean that something is wrong with your child. What it means is that something is "off" that needs to be assessed by someone with greater experience and expertise than you or the other adults (including professionals your child may be in normal contact with) possess. In my professional experience, there have been numerous times when a client, a teacher, or I myself have noticed that something is "off" with the child, referred the child to be assessed by someone with greater expertise and training, and have the expert almost immediately recognize and nail down with the specific issue is for that child. And, the child who had been suffering unsuccessfully while dealing with his or her unrecognized and undiagnosed issue, had been able to be immediately given the specific training and support that he or she needed to be more functional and successful. Undiagnosed learning disabilities, undiagnosed neurological issues, undiagnosed auditory or visual deficits, undiagnosed vocational challenges, undiagnosed developmental delays, undiagnosed physical challenges, undiagnosed cognitive processes, and any other undiagnosed issue can doom a child to a lifetime of unnecessary suffering. This is daunting and even terrifying for parents to consider that their child might be "off." Every parent wants their child to be at least normal, if not exceptional. For parents to accept the possibility that their child may have some special challenge causes them to experience a profound grief/loss process. This may cause them to get stuck in the first D, the Denial of the DABDA process -- denial that anything could be possibly wrong with their child... denial that their child will have to work hard and suffer through his or her challenges. Unfortunately, the failure to accept and go through this process, will cause their child to suffer needlessly and not get the help that maybe readily available -- and highly effective.

IS THIS A HAPPY CHILD?

A happy child can be a goofy child! A happy child can be an active child. A happy child may lose control, have a temper tantrum, get into fights, become sad, anxious, fearful, and angry at times. A happy child may have occasional odd behavior or even, periods of odd behavior. However, a happy child usually is able to receive and integrate discipline and support so that he or she can be successful. If there is behavior that is of concern to parents or teachers, there should be greater concern if there are any answers of "Yes" to any of the first five questions: "Is this an angry child? Is this a sad child? Is this an anxious or fearful child? Is this a child that is holding loss or pain? Is this an ‘off’ child?" However, if the answers are "No" to all of the first five questions and "Yes" to the last question whether he or she is a happy child, then in all likelihood, as long as the adults involved are reasonably healthy, informed, and involved, that normal discipline, classroom management, and adult support and guidance will be sufficient to handle the behavioral, educational, emotional, and social challenges. Adults should turn their energies toward addressing developmental issues, specific situations, the child's physical condition, disruptions in the routines of the family or school, personality or temperamental challenges, and the dynamics of the child's social situations. I will discuss a hierarchy or process to approach problematic or challenging behavior of children in the next article.

If you have answered any of the first five questions with a "Yes" then it is critical to address the underlying causes that exist or have manifested in your child. If, on the other hand, you have a happy child, there is still a lot of work to do. However, your high anxiety (amorphous and undifferentiated anxiety without a specific object or focus) and urge to be hypersensitive and hypervigilant will not be so necessary. You can be "just" sensitive and vigilant about your child!

Oh my gosh! I can't believe she could do that! You wouldn't think something that big could fit into something that small! Okay... it's parent time. Time to do the old discipline thing... or is it, the new discipline thing?Where do I start? How do I start? Reason with her? Distract? Do expectations? Trick? Motivate? Coerce? Punish? Threaten?Wait... what's it all about anyway? A maturity thing? Circumstances? Fatigue? Hunger? Getting sick? A disruption? Personality? Are we all nuts? Is there something wrong or off? Did the devil make her do it?Shoot, it's not parent time! It's the daily discipline detective time!

IN LOVE WITH YOUR HAMMER

Many people discipline from one perspective only. The perspective may differ from parent to parent, but what all of these parents have been common is that they assume that there is only one reason for the behavior (or misbehavior) and therefore only one approach or even one discipline in response. What happens when you fall in love with a hammer? Everything starts looking like a nail! Bam! Bam! Bam! Some people fall in love with or get stuck with only one way to understand behavior and only one approach to respond to it. Years ago, I remember reading a study where it was found that a significant percentage of parents of preschoolers use corporal punishment to discipline their children, despite the spankings not working to eliminate the behavior! Such parents may not have fallen in love with this simplistic approach to discipline (that behavior that is punished will be eliminated), but have been stuck with it because this was their original model from their childhood and there had been no re-examination or introduction to appropriate discipline.

Quite often, when I conduct a training for parents or teachers, someone will come up to me and asked, "Is it OK if I ___________ my child?" My normal response is, "Does it work?" A common response to me is, "Well... not really." Then my response is, "Then why are you asking me if it's OK!?" Not only are people stuck in doing discipline that does not work, they seek permission to continue doing the discipline that does not work! "Is it OK if I keep on use this hammer to bang on this screw, even though it isn't going in straight and is getting all bent up?" Discipline techniques are tools to help deal with behavior and discipline issues. However, as with all tools, they can be properly used or improperly applied to the wrong task. A hammer is great for driving in a nail, but a poor choice to chop wood with. As with all tools, they can be very useful, as well as quite dangerous. In addition, an appropriate tool can be chosen to complete a desired task, but the task may not actually serve the overall goal. A Phillips head screwdriver is the correct tool to use to screw in a Phillips head screw. But using a Phillips head screw is not the best way to attach a button to a shirt! The following hierarchy of discipline discusses overall principles in approaching affecting the behavior of children. It seeks to be logical, to be careful of what the adult teaches when he/she disciplines, to be responsive to the child, and tries to give children responsibility but also attempts to keep the adult's responsibility to be the adult. The diagnostic hierarchy that follows later in the article, discusses the various underlying principles or reasons for behavioral challenges, and suggests appropriate approaches to match the underlying principles or reasons.

It is very important to note that before any attempt at discipline, there needs to be CONNECTION. Being in tune to the feelings of the child, and then validating him or her no matter the effects of his or her actions. The feelings of upsetness, of being wronged, of being angry are always real and valid to the CHILD, whether the circumstances and situation justify the actions and results or not. If you skip this connecting/validating process, none of the discipline steps will be really absorbed by the child!

Level 1: THE CIVILIZED APPROACH

These principles need to be kept in mind at the second and third levels as well. (This is what most of us promise to do until we have real children to discipline!). It is important to be reasonable with children. Present reason and logic to the child. Be clear about what is acceptable and unacceptable. Sometimes adults forget to tell children, "That is not OK." Children are often testing boundaries and simply need to be told that the boundary exists right here. Sometimes, they are not even testing boundaries (which implies that they want to extend the boundaries), but are actually just looking for the boundaries. As soon as they are told, that these are the boundaries, then they relax and become secure in their behavior. Explain to them what the logical consequences (negatives and benefits) of their behavior will be on others. Explain what the expectations are for their behavior. This trusts and values the children's ability to be reasonable. Positive expectations are often met with positive behavior. However, remember that some people are unable to be reasonable for various reasons. Reason works with reasonable people. In addition, let the children know how their behavior can both please and displease parents and other adults. This works with the children's natural instinct to please those important to them. Discipline from this perspective, is a process of socialization to be a member of the community -- a civilized community.

Level 2: CREATIVE/LOGICAL SERVING MOTIVATIONS

This approach is dependent on finding the individual keys to situations and personalities. The adult needs to be discerning and evaluative as to what the child desires in the situation. Children need to feel the logic of the motivation as to how it serves them. Such logic is internal and self-serving for children. Caring for others feelings and needs as a motivation for change may not work with younger children. That may be developmentally challenging for the very young (unfortunately, sometimes also quite challenging for the quite old!). However, logic for children is normally very short-term. Long-term consequences are not real to them. Putting things in terms of short-term consequences is important. Frame the choices of behavior from the benefit or loss that children will receive. The adult needs to include in the choices, the limitations that the adult will enforce. In other words, that the adult will not allow a positive benefit when a negative choice has been made, and that the adult will ensure a negative consequence when a negative choice has been made! "If you choose this, then this is what will happen (positive). If you choose that, then this is what will happen (negative). Or, since you chose this, then..." Be clear that the consequences are a result of the behavior and choices. Children will often do things impulsively without any consciousness of the ramifications of their behavior. Helping them see how this affects their life, their opportunities, and their happiness is critical to their development.

Level 3: PUNITIVE AND COERCIVE MOTIVATIONS

This is, unfortunately where many of us often do our disciplining, sometimes harmfully. We skip the second level after attempting to reason with children, become frustrated or cannot figure it out, and move toward punitive and coercive motivations. A common coercive discipline is to use distraction. Sometimes it is appropriate to distract children from something that they are obsessing over and that causes them to behave negatively. It may be useful to teach children how to distract themselves from frustrating experiences that would otherwise cause them to misbehave. On the other hand, overused and misused distraction can present a negative message to children. When children are upset about something, the things that they are upset about are the focus of their disturbance, distress, anxiety, or sadness. Distracting them from such things may give them the message that their urgencies are unimportant -- that their feelings of disturbance, distress, anxiety, are sadness are irrelevant and to be dismissed. This is a highly dangerous and negative existential message, "Your feelings don't matter!" Distraction can be okay if it includes the message, "I know you feel really bad. Let's see if doing this will help you make yourself feel better." This both acknowledges the feelings and frames the distraction as a way to soothe the feelings rather than ignore them.

External motivations can be sometimes effective in disciplining children. This could be rewards... or bribes! It can be scoldings or punishments such as timeout or spanking. Such motivation, both positive and negative should be kept as relevant and logical to the situations as possible. Positive motivations such as rewards tend to be easier to manage. The rewards are expressions of approval for positive behavior. It is easy to be pleased with your child's behavior. The rewards are often secondary to the goodwill and positive energy the child receives. On the other hand, be very careful when offering reward for the lack of negative behavior. This discipline double negative does not focus children on positive behavior, but focuses them only on the avoidance of negative behavior. Positive behavior gets overlooked and only when the child messes up, will there be attention and punishment. Negative consequences should fit the negative behavior. If the child is riding his or her bicycle dangerously in the street, then an appropriately motivating consequence or punishment is to be denied the right to ride his or her bicycle for the next week. On the other hand, losing television rights for the next week is not as relevant or logical to the situation.

An appropriate way to frame punitive discipline may be to look at the time expended as a consequence of the behavior. When a child misbehaves, he or she creates a need to manage the disruption that takes time away from other issues. When a child throws a tantrum; it takes time to settle him or her down; to clean up the mess; or to stabilize the other people in the community. All this takes time away from the adult and others. An appropriate way to approach giving the child a consequence is to format the consequence in such a way that the adult and others regain lost time, and the child who threw the tantrum expends his or her time restoring others lost time. An eight-year-old who threw a temper tantrum selected as his consequence, that he fold the laundry that his mother otherwise would have done. This gave the mother about 10 or 15 minutes of time to sit and read a magazine. She felt it was a good deal for her!

Level 4: COLLABORATIVE APPROACH TO CHILDREN

Or when nothing simple seems to be working! Sometimes, children’s behavior is not merely about discipline, but also about the community that they exist in. Then it is important to look at the overall and overlapping communities of the child. Is there consistency between all involved (between parents, between parents and other important adults including teachers) so as not to confuse them? Is there effective information exchange between all parties to clarify behavior and responses, and share expertise (parent to teacher & teacher to parent)? Is there an exchange of insight between everyone to disclose and evaluate possible underlying reasons for behavior?

Level 5: TAKING A HARD LOOK AT THE INDIVIDUAL

It is important to distinguish common developmental and discipline issues with more severe and less common challenges that interfere with the integration and processing of internal processes and inter-personal communication. If problems persist, professional consultation would be highly recommended, as opposed to hoping that children will "grow out of it." Be sure to find the right professional. While many parents turn to their children’s pediatricians, pediatricians’ expertise is primarily in physical medical health and development. Early childhood educators, developmental specialists, neurologists, speech and language professionals, mental health professionals, vocational therapists, and other specialists are often more appropriate to consult depending on your child’s issues.

A DIAGNOSTIC ORDER FOR UNDERSTANDING & APPROACHING BEHAVIOR

This material was developed in response to parents, teachers, and social services professionals who needed a systematic process to understand the motivations behind children's behavior (and adult behavior as well!). Often adults make assumptions about what may be the reasons behind children’s behavior. Children may exhibit the same behavior for a multitude of reasons. A child who hits may be hitting for any of a variety of reasons. While punishment may stop the child's immediate behavior, it does not address any underlying issue, which may cause the behavior to repeat itself in the future. Although, it is usually important to set boundaries regarding the behavior, adults also need to understand what causes the behavior in the first place. As long as underlying issues continue to exist, the behavior often reasserts itself or is not responsive to boundaries.

This suggests an orderly diagnostic process, starting with looking at things from a developmental perspective to higher levels of concern. In many situations, several of the issues may apply to the child. Some people have a favorite theory to explain why children behave a certain way and as a result, always look to that theory for guidance. Unfortunately, in the more complex situations, behavior is activated by a combination of issues. For example, a high-energy distractible 6 year old boy who is tired, has watched a lot of violent television and plays a lot of violent videogames, has emotionally neglectful and physically abusive parents, in a poorly managed and crowded classroom, frustrated with academics because of a learning disability during the Christmas session may… in fact, probably will act out. It may be more convenient to narrow down the underlying issue to one theory, but it is neither appropriate nor effective. It is important to address all the relevant issues and not just the ones that the adult is the most familiar with or comfortable with. Put away your hammer and pull out the entire tool chest!

1) DEVELOPMENTAL FACTORS

Fidgety, putting things in the mouth, touches everything, can't stop making noise, and is... six months old! Hmmm, that's OK. And is one year old. Hmmm, that's still OK. And is four years old. Well, I'm a bit concerned. And is 10 years old. Now, I'm worried! And is 35 years old! Oh oh! The greater concern as the individual is getting older comes from an expected gradual internalization of social expectations about what is appropriate behavior as far as sitting still, touching things, and being quiet -- polite and respectful. The older the person is, the more one expects him or her to self regulate his or her behavior. Often times, the behavior of the child is actually appropriate according to his or her developmental stage. Although the behavior may be challenging (or messy! Or very loud!), it also may be normal behavior for a child at that age. When developmental behaviors are frustrated, there are often even greater problems because of developmental needs will continue to assert themselves. The basic approach is to find a way for such developmental needs to be satisfied in a safe and appropriate manner. For example, running outside to take care of physical energy rather than getting into trouble being active inside. The basic question is, "Is what my child doing OK for children of his or her age?"

2) SITUATIONAL FACTORS

Two kids and one new toy truck! Five people in the family and one bathroom! 10,000 applicants for 3,000 college spots! Sounds like trouble! Sometimes, the situation, usually a shortage of resources (toys, for example) is the main cause for a problem. Changing the availability of resources (making another toy available, for example) may be an effective approach. On the other hand, sometimes socializing children to share the resources can be effective (how to take turns, for example). Conflict and the accompanying negative behavior may arise as individuals anticipate a situation where there may be a shortage of resources. For example, in the line of shoppers outside the shopping mall for the early bird after-Christmas sale!

3) PHYSICAL FACTORS

"Are you feeling OK? You've been a bit cranky today." The physical condition of the child often affects his or her behavior. Basically, this is being sick, tired, or hungry. Often children misbehave because they are sick, or sometimes, because they are getting sick. If they are not yet showing that they are sick, this can be very deceptive. Many teachers and parents in retrospect will realize that a child who is reporting in sick today, was acting up yesterday! They felt lousy yesterday and acted out without being aware that they were getting sick. Getting children healthy is the logical approach. Children who are tired often act out quite a bit. The obvious approach is to help them get enough rest. Unfortunately, it is easy to forget that tired children behave poorly. I had a little girl in my preschool program who sometimes would come to school after having stayed up late. On those days, instead of being the little sweetheart, she was the nastiest grumpiest little girl you ever met! Fortunately, her mother learned to warn us and as soon as she started to fall apart, we would put her to nap. We didn't care if it was 7:30 a.m.; we put her to nap for everybody's well being! And hungry children? Feed them! A second grader was not doing well in her core topics. Most of these core topics were taught in the morning. This kid would not eat breakfast and would be operating on low blood sugar the entire morning (at lunchtime when he would finally eat, it would be as much as 18 hours after he had last eaten at 6 p.m. the night before). Getting him to eat breakfast made him a better student. Of course, don't adults who diet can get awfully grumpy as well as!?

4) EMOTIONAL CONDITION/DISRUPTION

Everyone tends to live his or her lives in a rhythm. When that rhythm is disrupted, some people react with disrupted behavior -- misbehavior. Adults sometimes do not recognize that there are things that disrupt children that they would not otherwise notice: a holiday, a visit from Grandma, a change in the schedule, someone new in the family or the class, and anything else that is different or not part of the normal routine. My wife, a kindergarten teacher at the time told me about a little boy who just couldn't seem to do anything correctly for the week. After a few days, she asked him what was going on with him because he was so behaving so differently than usual. Virtually vibrating with excitement, he said, "I'm going to Disneyland on Saturday!" Adults should try to anticipate when there are changes that may be disruptive to the child. Letting the child know ahead of time and giving him or her time to acclimate to the change helps a great deal. Reassurance that the disruption will not be enduring also often helps. In addition, sometimes disruptions in the adults' life resonate through the family and cause children to be disrupted as well. Children may react negatively to a parent’s work schedule that has changed, which in turn has caused the family schedule and routine to change.

These first four sets of factors or issues are very commonsensical, but are sometimes forgotten when adults are under stress. It is useful to think of them and to use them in order. They are based on the KISS principle -- Keep It Simple, don't be Stupid! Sometimes parents become hypervigilant and over worried, and basically scare themselves with more complex and convoluted negative theories about behavior. Keep It Simple, don't Scare yourself! Look for the basic issues first. In addition, the next two sets of factors are very important because when they are forgotten, people move too quickly and dangerously into the last two sets of factors. The last two factors, while potentially very important, can if applied too quickly cause problems for everyone.

5) TEMPERAMENTAL ISSUES

Anyone who has two children or more should know this instinctively – kids are born different. Women often say that they could tell the difference during pregnancy, as the activity level of the children was different well before birth. Each person is born with a distinct set of temperamental traits -- a unique personality. The mix of temperamental traits creates both positive and challenging personalities for people. Sometimes the challenge is for the individual. Sometimes the individual's temperament is the challenge for other people. Also, sometimes the temperament of one person may match up very poorly with one person, while matching up very well with another person (you know... how you can't stand some people, while your partner just adores them!). It is important for an adult to understand his or her own temperament and how it matches up well or poorly with the child's (or colleague's, or spouse's). It is the initial responsibility of the adult to be self-aware of his or her own temperament, and to regulate his or her and his or her child's behavior according to the match or mismatch to make the relationship more successful. I will expand upon temperamental theory and its effect on behavior and relationships in the next article of this series.

6) ENVIRONMENTAL/ECOLOGICAL FACTORS

Every child and person operates within a system (often, multiple systems) of people such as a family or a class or a workplace. Earlier in this article, I mentioned collaboration between the different communities or systems of the child. Here, I am emphasizing the actual health of each of those systems. In other words, sometimes an "out of control" child behaves in such a manner because he or she is in an "out of control" family or classroom. Dysfunctional systems create extraordinary demands that may be beyond the capacity of children to handle without problematic behavior. The behaviors, the communication style, and the health and stability (or lack thereof) of the system can cause significant emotional, psychological, and behavioral responses from the child or person in the system. When the system (family, class, or workplace) is too unstable or unhealthy, directing all of attention energy toward the child and his or her behavior may be inappropriate and unsuccessful. Often, it is important to direct energy towards making the system more stable and healthy. Without the system becoming more stable and healthy, the child cannot get better.

7) PATHOLOGY FACTORS

In some situations, there may be something "wrong" or "off" about a child. Many, if not all parents fear that there may be something "wrong" about their children. Some parents become hypervigilant and even paranoid that something is wrong about their children, and they see issues where there are none. Other parents are so disturbed and overwhelmed by the possibility, that they deny or ignore clear signals that the child needs special attention and help. There can be significant issues that are biochemically based or from some other fundamental issue in a person's makeup that is especially challenging. ADHD (Attention Deficit Hyperkinetic Disorder) or ADD (Attention Deficit Disorder), autism, and learning disabilities may be issues that some children have (or adults have). Such issues, if applicable (great care must be made before making such diagnoses because of the stigma attached to them) need to be addressed with guidance from professionals. And, often treatment needs guidance from professionals as well. Unfortunately, many people (including professionals) often jump to this level of diagnosis inappropriately. This can often lead to people (such as teachers) becoming dismissive of the child, claiming that the child is beyond their scope of practice and experience.

8) MORAL FACTORS

"Bad Boy!" "Bad Girl!" All of the other factors need to be examined first, primarily to avoid parents and other adults making a negative moral judgment against the child. Even the most seemingly amoral children (or adults) normally had major problems in the earlier (lower levels) of issues that were poorly handled. This is the ultimate negative diagnosis and lead directly to dismissing the child as being beyond salvation.

There are other ways to look at the underlying causes of behaviors. This diagnostic hierarchy is an approach that I have used that has often has often proved to be useful. A single page chart version with short additional explanations is posted on my web site, A single page chart version with short additional explanations is posted on my web site, www.RonaldMah.com in the Handouts section as "Diagnostic Order for Understanding and Approaching Behavior." In the next chapter, I will expand on temperamental theory as it applies to children's behavior and relationships. It is very useful in looking at not only children's behavior, but also couples relationships, families, and workplace dynamics.

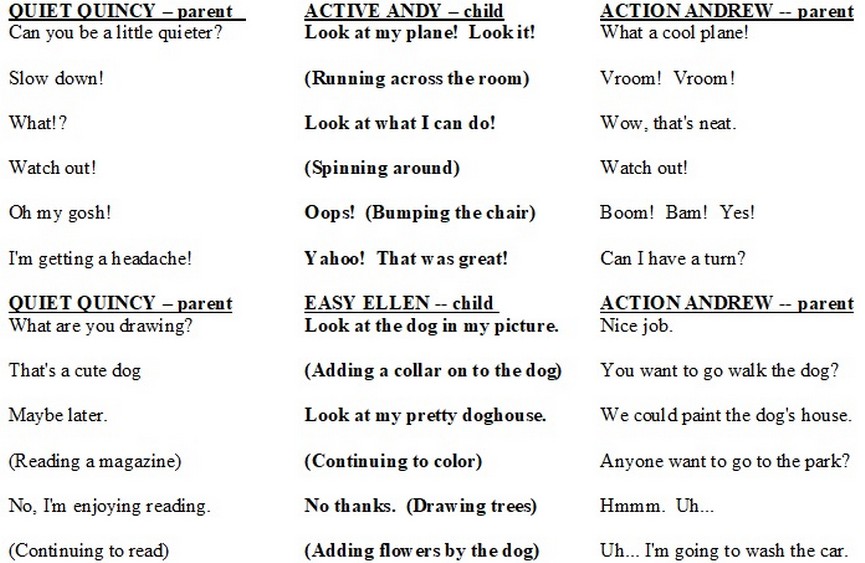

The parents, Quincy and Andrew have two children: Andy and Ellen. They both love their children dearly, but Quincy and Ellen get along very easily together. Both Quincy and Ellen like more sedate activities and would be perfectly content to spend the day doing quiet activities at home: reading, doing arts and crafts projects, cooking, etc. Andrew and Andy also get along very well together for the most part. They are like two peas in a pod -- or perhaps, like two jumping beans in a jar! Half the time, Quincy thinks that Andrew despite being the dad seems to instigate the wild play that get Andy charging around the house. Andy and Andrew were both full energy most of the time. Quincy is a great mom to Andy but to be honest, Andy just wears her out sometimes. Quiet time for Andy is boisterous, active, and not particularly quiet for Quincy's comfort and expectations. As much as she hates to admit it, sometimes she just needs a break from Andy's energy. Sometimes, she needs a break from Andrew’s energy, too! He can be just as bad. On the other hand, Andrew doesn't have any problem with his daughter Ellen. Ellen is Andrew's little sweetheart. Andrew figured out pretty early that Ellen didn't like the rambunctious play as much as he did or that Andy loved so much. Ellen did play with Andrew and could get active at times, but it just wasn't her preference. Ellen also played great with Andy and could keep up with his rambunctious play, but she could take that kind of play or not. Actually, Ellen got along pretty easily with everybody. This match and mismatch of family members is not unusual in many families. One member of the family may be often highly attractive to and compatible with a second family member, while having a hard time getting along with a third family member. On the other hand, a fourth family member may get along great with that third family member -- and perhaps, not get along particularly well with either of the first two family members. While this can be due to dysfunctional dynamics in the family and/or poor parenting, oftentimes the dynamics can be due to simple temperamental differences that each member of the family is basically born with.

DIDN'T HAVE THE CHANCE TO RUIN HER

I have two wonderful daughters who, from birth, showed different personalities and temperaments. One daughter was born with a fairly mellow temperament. On the very first day, as the nurse was changing her diaper, the nurse said to her, "How are you doing, little baby?" My daughter gazed at her with open calm eyes. The nurse exclaimed to us, "What a little sweetheart you have!" I responded, puffing out my chest, "Of course, it's genetic!" Throughout her childhood and now as a young adult, she continues to have this fairly mellow temperament. If she were told "no," she would be disappointed but take it with good grace (sometimes, offering a reasonable alternative in an effort to negotiate her point). My other daughter (and don't get me wrong, she's a wonderful person!) was born with a somewhat more intense temperament. On her very first day, as the nurse was changing her diaper, the nurse also said to her, "Hi little baby... how are you?" This daughter looked her in the eyes and screamed at the top of her lungs, "Ahhhhh!” I quickly pointed at my wife lying wearily in the bed, and said, " Uh…Of course, it's genetic! That tired looking lady over there!" Throughout her childhood and even now as a young woman, she has always been our passionate child who feels deeply about everything. This has made her a lot of fun. And sometimes, somewhat challenging! How could this be with the same pair of parents and the same basic parenting style for both children in the same household? It must be temperament that is in-born, because I didn't have the chance to ruin her! She came out that way!

This is about temperamental differences, but also about hyperactivity a little bit, and the different ways we look at kids' behavior. In terms of hyperactivity, the 64 thousand dollar question is "I got this wild kid! What the heck is going on? (What the heck is wrong?). For another child, the question is why is he/she so careful and cautious in new situations? For another child, the question would be how could we help him/her do with his/her frustration? For still another child, the question may be why is it so easy for him/her when it is so much harder for other kids? Distinguishing temperament is important to help you understand that nothing is "wrong" -- there is nothing "wrong" with the child or the parent or teacher. Temperamental differences are entirely normal. There is both a range of temperaments and common combinations of temperamental traits. Temperament is definitely something going on that needs to be understood when examining behavior. How one deals with the child or situation is based on one's diagnosis of what is going on. With each diagnosis, there are assumptions of cause and assumptions for treatment or interaction or discipline and so forth, and implications and judgments about who/what the child is. And, there is a resultant tolerance for the behavior and the child. And, temperament absolutely applies to the behavior of adults as well. The previous article puts temperament into a hierarchy of examining behavior.

AVOIDING MISDIAGNOSIS AND PATHOLOGIZING

Temperament and family systems issues are often the two areas that people misunderstand or misinterpret which can cause significant misdiagnosis and harm to children. Temperament and family systems issues often allow invested adults to avoid sliding into pathologizing children. This includes the ADHD -- attention deficit hyperkinetic disorder diagnosis. While this can be an important diagnosis to consider, often it is applied far too quickly and without the clinical rigor it should demand. In addition, it is a diagnosis that tends to lead to readily -- and in some cases, inappropriately to medication with stimulants. Even when medication is indicated, the behavioral approach to dealing with ADHD issues can be guided using the principles of the temperamental evaluation. When temperament is not understood and respected, it can lead to negative dynamics in the family or in the classroom. Parents or teachers falsely assume that the behavior is intentional and defiant, rather than due to the natural energy and temperament of a particular child. In addition, adults sometimes fail to take responsibility as to how their natural energy and temperament ignites, exacerbates, and otherwise interacts with certain children's energy and temperaments. On the other hand, adults also sometimes take too much responsibility for the "good" and positive behavior and relationships some children have when it is essentially about either a good match between those children and adults or a temperamentally easy child. A temperamentally easy child is easy to parent and easy to teach-- and relatively difficult to ruin!

Temperament is the natural, inborn style of behavior of each individual. It is the how of behavior, not the why. It should not be confused with motivation. The question is not "why does he behave a certain way when... but how does he/see behave when...” The particular style of behavior is innate for each individual. It is not produced by the environment; babies and children are not blank or empty slates that are filled through environmental influences. The environment and the behavior of a parent, a teacher, other adults, and eventually, peer and media and other cultural factors- can influence temperament and interplay with it, but it is not the original cause of temperamental characteristics.

THE DIFFICULT CHILD AND EFFECTS ON OTHERS

What happens with a difficult child? the wild child? There is often a vicious circle or cycle of wear and tear on both the child and those in intimate relationships with the child, such as parents, siblings, classmates and friends, and teachers. The primary caregiver takes on the greatest responsibility for caregiving of children (traditionally, the mother would be the primary caregiver) and can suffer a multitude of effects: bewilderment, exhaustion, anger, guilt, embarrassment, inadequacy, depression, isolation, victimization, lack of satisfaction, feeling trapped, over-involvement. In a two-parent family, the secondary caregiver (often the father in the heterosexual nuclear family) is not as active in direct caregiving, but drawn into the dynamic in a multitude of negative manners: the secondary caregiver feels shut out, questions what other parent is doing, the primary caregiver has no energy for the partner, and the primary caregiver can become jealous of secondary caregiver's relatively conflict relationship w/ the child. Siblings can get lost in the drama of the difficult child's behavior, as the difficult child draws an unusually disproportionate percentage of the energy of the parents. I once had a client -- a young man who exhibited the classic behavior of the Hero or Responsible One in the alcoholic family system. In the alcoholic family system, the alcoholism of one of the parents draws all the energy of both parents and leaves it to one of the children to take on the responsibilities of practical parent issues. This person is characterized as the Hero. However, as I examined his family history and experiences, there was no alcoholism or drug abuse among his siblings, his cousins, his parents, aunts and uncles, grandparents and great aunts and great uncles. A few sessions later, he mentioned how difficult his brother was when they were younger. It turned out that his brother was severely hyperactive and made life crazy for his parents. There was always a crisis and a drama for his parents to deal with because of his brother. As a result, someone else had to take care of the basic functioning of the household; he became the Responsible One. He became responsible for taking care of everyone else -- except for himself. This caused him problems in his relationships as he grew older.

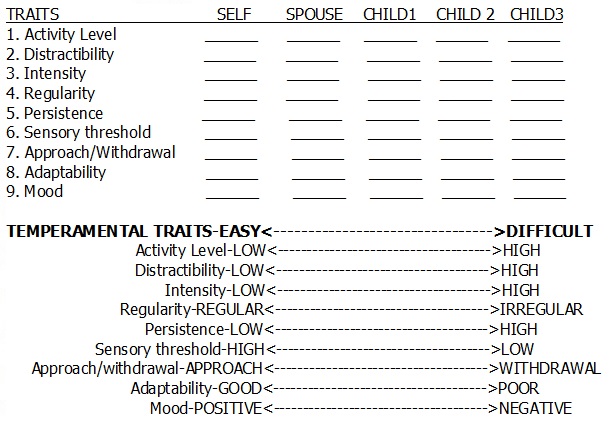

TEMPERAMENTAL EVALUATION TRAITS

There are many different theories on temperament. "The Difficult Child" by Stanley Turecki is a very readable and understandable resource. The following temperamental traits are taken from his book, which is based largely on the work of Stella Chess and Alexander Thomas. There are other ways to look at temperament and other ways to break down temperamental traits. I have found this one to be very useful. Look at each of these traits and rank yourself and everyone else in your family. It is important to note that high or low in any trait is not implicitly good or bad. Also, there is not necessarily any absolute scale by which to rate people. The relative ranking of members of your family is the most important. With one couple I worked with, the husband rated himself high in the activity level trait and his wife medium in the same trait. His wife, on the other hand, rated him medium activity and herself, low activity. What was important and what they both agreed on was that he was higher in the trait than she was. What was subjectively high activity level versus medium activity level versus low activity level was not as important. When there are several family members, the ranking of the different traits becomes easier because often it is relatively easy to see how two family members are both similar in one trait while both being higher or lower than a third family member.

1. Activity Level: How active generally is the child from an early age?2. Distractibility: How easily is the child distracted? Can s/he pay attention?3. Intensity: How loud is the child generally, whether happy or unhappy?4. Regularity: How predictable is the child in his/her patterns of sleep, appetite, bowel habits?5. Persistence: Does the child stay with something he likes? How persistent or stubborn is s/he when wants something?6. Sensory threshold: How does the child react to sensory stimuli: noise, bright lights, colors, smells, pain, warm weather, tastes, the texture and feel of clothes? Is s/he easily bothered? Is s/he easily over-stimulated?7. Approach/withdrawal: What is the child's initial response to newness- new places, people, foods, clothes?8. Adaptability: How does the child deal with transition and change?9. Mood: What is the child's basic mood? Do positive or negative reactions predominate?

The following is a chart that you can use for this temperamental evaluation.

Once you list and rank the traits for the entire family, you need to do a self-evaluation and evaluate your temperament for how well or how poorly the temperaments fit each other. Sometimes, it is very clear that there is a misfit between two members of the family, but the parent or other family member assumes that it is the other person who should and needs to change. It is important to recognize that as the adult (with the wisdom and experience!) comes the responsibility to make the changes and adaptations in the relationship. Each temperamental trait and the combination of traits create both potential strengths and challenges for the individual and relationships. Young children are often developmentally unable to self-monitor -- to be self aware of their temperament and their issues and how it affects their behavior and other people. In addition, there are also often developmentally unable to self-regulate -- to tell themselves what appropriate choices to make in order to be successful in their lives. It is the responsibility of the adults to monitor the children (and themselves) as to how their temperament creates problems versus opportunities for them and to regulate the children (and themselves) as to what choices to make in terms of their behavior. Theoretically, babies have 0% ability and responsibility to self-monitor and to self-regulate. Parents raise their children to become adults where they would have 100% ability and responsibility to self-monitor and to self-regulate. As adults consciously with love and caring monitor and regulate their children, they need to also explain to the children what they have observed and why they are requiring the children to behave. As they monitor and regulate, parents also need to educate their children to understand their temperaments. As with all personal issues, you cannot change with you do not own and cannot own what you're not aware of. As parents educate their children to understand the own their temperament, they enable their children to take responsibility to accentuate the strengths from the positive aspects of their temperament and to mitigate the challenges from the negative aspects of their temperament.

I'M A BIG GIRL NOW

One of my daughters was initially (temperamentally) low in persistence. If something was difficult, she had a tendency to give up on it. We experienced this problem early on with the normal processes of development. When she was about eight years old, she wanted to take piano lessons. We checked with her to see if she was really interested in piano lessons. She assured us enthusiastically (of course, enthusiastically is how she tended to express everything -- she was our passionate one!). We decided to go ahead and start her on lessons. After a couple of weeks, she became frustrated at her lack of immediate process and wanted to quit. We did not let her quit. We told her that she had to keep on trying. In addition, we also told her that she had a problem with being too ready to quit. That she needed to learn how to keep on trying -- to be persistent or else she would not be able to learn and get the things in her life that she would really enjoy and benefit from. She continued and ended up loving piano and taking lessons for several more years. When she was in the second grade, we checked to see if she wanted to play basketball with a recreational league. She said she really wanted to and we enrolled her in an organization that sponsored youth basketball. After a few weeks of practice, she decided she didn't like it and wanted to quit. We did not let her quit. We told her again, that she had to keep on trying -- that she needed to follow through on her commitment to the team and to really give it a chance in order to see if she really liked it, and if she would be good at it. She continued and ended up playing not only in the recreational league but also for her school team through middle school. Basketball proved to be a formative and wonderful experience for her. We not only monitored her and regulated her around her low persistence issue, we also educated her about her challenge in this area. We did not blame her or shame her, but consistently fed back to her about how this was a challenge that she needed to learn how to address. Basically, how in this particular case with this particular trait, that she needed to learn how to go against her instincts in order to have more positive experiences and outcomes. In the fifth grade, we went to a parent-teacher-child conference at school to discuss her academic progress. The teacher noted to us that she had experienced our daughter sometimes getting very frustrated at having a hard time with a particular assignment, but then applying herself with determination until she could do it correctly. Teasingly, I told her, "But I thought you gave up easily and liked to quit when things got hard?" With a big grin on her face, she replied, "I'm a big girl now!" The big girl had internalized that she had a challenge in her temperament regarding persistence, accepted the challenge, and successively self-monitored and self-regulated so that she could be successful. From 0% ability to self-monitor and self-regulate as a baby, she had moved strongly toward 100% ability.

Little girls and little boys become the girls and the boys -- become young women and men who have greater or lesser ability to be aware of their strengths and weaknesses and greater or lesser ability to make adaptations to be the most successful. Your awareness of your strengths and weaknesses, including temperamental traits is critical to helping them become aware and empowered to be the most successful. The next chapter will have more discussion about the specific traits and potential strengths and challenges for your child.

Ronald had been working all week as the director of a small preschool and day care program. 50 kids in the school, six to seven teachers to supervise, 50 sets of parents and associated siblings and family members and friends, a dozen prospective students and parents, a couple of vendors, and an occasional licensing or government representative. Finger paint, field trips, music (cymbals, rhythm sticks, bells, kazoos, drums, beautiful voices -- and not so beautiful voices!), tricycles, puzzles, playhouse games, dress ups, water play (and water messes), books, blocks, sharing, not sharing, discussions, arguments, fights, bumps and bruises, disinfectant and Band-Aids, happy kids, sad kids, mad kids, happy parents, mad parents, scared parents, happy teachers, good teachers, poor teachers, smiles and frowns, laughter and crying -- peace and calm, NOT!Kim had been working all week as the kindergarten teacher of a small private school. 16 kids in her classroom, 15 other teachers, 20 sets of anxious parents, a couple of prospective students visiting the class, a couple of meetings with fellow teachers, parents, and the administration. Arts and crafts, field trips, music (cymbals, rhythm sticks, bells, kazoos, drums, beautiful voices -- enthusiastic voices!), puzzles, games, dress ups, water play (and water messes), books, lessons to teach, sharing, not sharing, discussions, arguments, fights, bumps and bruises, happy kids, sad kids, mad kids, happy parents, mad parents, scared parents, happy colleagues, good coworkers, poor, smiles and frowns, laughter and crying -- peace and calm, NOT!Friday night, Kim and Ronald are home together. Finally, a break from work. Finally, some time together. Ronald says, "Hey, let's go out. Let's go dancing, or go bowling." Kim responds, "Why you doing this to me?" as she fixes him with a death stare! "Whaaat?! What do you mean,’ doing this’ do you? What did I do?” a stunned and confused Ronald replies. (Based on a true story -- a true story that wasn't funny living as it happened!)

UNJUSTLY ACCUSED

What did Ronald (that's me!) do to Kim (that's my wife)? What was so awful about suggesting that they go out -- to do something fun like go dancing or go bowling? There was nothing awful about wanting to go out or wanting to spend time together doing something that would be fun for both of us. I was perfectly willing to do something else if it was something that she really wanted to do. But somehow, I was being accused of being insensitive, hurtful, intrusive, and causing winter flooding... and causing the melting of the Arctic ice cap! And just like Richard Kimball of "The Fugitive," I was appalled at been "unjustly accused!" Little did we realize at this relatively early time in our living together, that there was something that I "did" that disrupted my wife. While at that time, neither one of us really knew what it was and why it was so upsetting; Kim had an expectation that I would act properly anyway. In fact, when I asked, "What did I do?” she was unable to do give me an answer. She just knew that I had done "it!" And, she resented it! Unjustly accused, unjustly tried, unjustly condemned -- and unjustly punished! Boy, what she mad at me! And, boy, was I mad at her for being mad at me -- unjustly! Eventually, we figured out that there was a basic temperamental difference between us with respect to a particular trait that caused this particular confrontation and problem.

Although, they both had been in weeklong work situations that exposed us and filled us both to tremendous amounts of stimulation that were fundamentally similar (administering a preschool program versus teaching kindergarten), our different sensory threshold levels created a differential effect on each of us. My wife was an outstanding kindergarten teacher: resourceful, sensitive, creative, dedicated, and hard working. However, compared to me she had a lower sensory threshold. While she was able to handle and deal with the incredibly high level of sensory stimulation (noise, physical stimulation, activity, and energy) of the kindergarten class and kindergartners, her capacity to hold such stimulation was not as great as mine. Obviously, she had a fairly high capacity to deal with such stimulation compared to many other people. There were many people, parents and even other teachers who would spend a few minutes in her classroom and eventually turn to her with wide eyes and say, "I don't know how you can handle this all day long!” with a certain amount of mixed respect and pity! On the other hand, I probably have an extremely high sensory threshold for noise and activity. When I was owning, directing, and teaching in our own preschool and day care program, there were periods (especially, in the early days of the business) where I would work the entire 7 a.m. to 6 p.m. schedule of the program on a regular basis. Rather than collapse after work, I might work out or play basketball with my friends. At the end of my workweek, I would have absorbed a comparable amount of stimulation, as she would have in her workweek. However, because I had a higher sensory threshold, I was still "good to go" and still had additional capacity to absorb even more stimulation -- such as go out and play as adults. On the other hand, Kim was "filled up" and was "running on fumes!"

At the end of a week, my sensory threshold allowed for more stimulation; an appropriate analogy would be that I had been "filled" with the stimulation line/waterline up to my chest. Obviously, there was plenty more capacity for more stimulation and activity. On the other hand, Kim sensory threshold had been reached; an appropriate analogy for her was that the stimulation line/waterline had come up to her nose, and she was desperately trying to keep her head from going under! My joyous, loving suggestion to go out was tantamount to dumping a huge barrel of stimulation/water on to her head as she was trying to keep from being submerged! How could I do that? "Why are you doing that to me?” becomes a relevant angry challenge from Kim if she believes that I know that she is struggling to keep herself from going under and I still am suggesting additional stimulation. What a jerk! I, of course had no idea that she was struggling to keep from being overwhelmed with the weekly stimulation, but had assumed that she was just fine because I was still just fine.

THE COSMIC YARDSTICK