17. Integration of Multiple Factors - RonaldMah

Ronald Mah, M.A., Ph.D.

Licensed Marriage & Family Therapist,

Consultant/Trainer/Author

Main menu:

17. Integration of Multiple Factors

Therapist Resources > Therapy Books > Ouch Borderline in Couples

Ouch! Where'd that come from?! The Borderline in Couples and Couple Therapy

Chapter 17: INTEGRATION OF MULTIPLE FACTORS

Therapy often leads the client to make accurate connections between his or her feelings, thinking, modeling, and his or her choices or behavior. The client may make inaccurate connections between what another does and his or her feelings, thinking, and motivations. Prompting the client's attention to his or her feelings may be sufficient to instigate emotional awareness and insight to key early experiences. When the therapist offers alternative interpretations, the client may find them insightful and alter his or her perceptions. In contrast, when some comment or triggers betrayal, abandonment, or rejection fears about the therapist or the partner, the individual with borderline personality disorder often has no idea that he or she was actually ignited by some previous attachment trauma. Therapist facilitated clarification prompts the individual to unfold and reflect upon his or her internal states. Clarification however does not usually enable the individual to integrate awareness and insight into his or her behavior or life readily. There remain emotional and intellectual conflicts to resolve. The therapist and the partner need to also confront the individual when verbal expression and non-verbal communications including behavior are contradictory.

Interpretation of how and why the conflicts exist or developed is necessary for the individual to see how he or she switches between experiencing him or herself and the partner in the current circumstances versus projecting prior older experiences onto self and the partner's interactions. Since the individual is often unaware and has little insight of these shifts, "Increasing the patient's awareness of his or her range of identifications increases his or her ability to integrate the different parts" (Levy et al., 2006, page 488). This is a critical process in the growth of the individual and how he or she experiences the partner and the relationship. It is also a very difficult process for the individual because "Movement toward integration initially causes anxiety because of the existence of the internal barriers that keep conflicting affects separate. The scenarios reexperienced with the therapist in the transference are not simply a literal reproduction of what the patient experienced in the past, but a mix of what happened, how the patient perceived what happened, and what the patient defensively set up to avoid awareness of aspects of conflicts that are consciously intolerable. Interpretations are hypotheses in which the therapist offers a cognitive formulation of the temporally split-off object relations as they are activated in the transference, and of the reasons that they remain separated. As the therapy advances, interpretations can address deeper levels of conflicts within the patient" (page 489).

Integration of past feelings with present feelings is a major challenge in therapy, especially since any therapist interpretation, confrontation, or clarification may be experienced as being made wrong… again. Moreover, the ultimate goal for integration of feelings is whether that leads to change in behavior. The individual may also experience being prompted to change his or her behavior as being made wrong once again. Identifying and admitting that his or her behavior is harmful or negative can feel like setting him or herself up to be rejected. On the other hand, through prior therapy or other experiences, the individual may have gained significant insight and awareness of underlying feelings and the formative attachment experiences that cause them. The individual may be able to own the dysfunctionality of his or her behavior. However, the individual who is "therapy-wise" and be able to own the dysfunctionality of his or her behavior, including being able to describe his or her borderline personality issues, nevertheless remains disabled unless he or she can change his or her behavior.

The therapist may find the individual with borderline personality disorder to be a "good" client who is psychologically well versed in his or her diagnosis. Rather than resisting connecting various experiences and factors, the individual may be quite agreeable. Pleasing the authoritative figure is a significant characteristic of the individual with borderline personality disorder. The individual may feel the therapist's approval for being so introspective, insightful, and open. The therapist on his or her part may enjoy the individual's compliance… be professionally self-satisfied that he or she has been able to get the individual to be so forthcoming. However within this mutual affection dyad, if the individual's life and relationships do not improve or self-destructive behaviors diminish… if the partner continues to be unfulfilled and disconnecting, then therapy has not been productive. The therapist has his or her own theoretical process of integrating all the clinical clues to form an accurate diagnosis, a coherent conceptualization of the each member's and the couple's dynamics, and develop a logical and effective therapeutic strategy and plan. The final integration criterion for the therapeutic process is individual's and couple's behavior change that improves life and relationships. The therapist must not lose sight of this. However, the therapist also should be wary of which behavior becomes the focus of therapy.

FOCUS ON PARTNER'S BEHAVIOR

When the therapist works with more than one individual such as with a couple or a family, the dynamics change significantly. Working one-to-one, the therapist can concentrate on the individual client and his or her words, affect, body language, and other important cues. The therapist may also find it relatively simple to be mindful or self-aware of his or her emotional, intellectual, and psychic experience with the client. Theoretically and therapeutically, this means to be attentive to his or her counter-transference. In individual therapy, the therapist may recognize the possibility of borderline personality disorder through gaining a broader history of the individual with a significant pattern of similar betrayals, abandonments, and rejections. And/or, the therapist experiences a borderline eruption of hostility at the therapist for some perceived transgression. The dyadic focus on the client and on oneself as the therapist is immensely complicated working with the couple or the family. "In order to establish a secure base for the whole family the therapist has to be seen to care most about what happens between all family members, rather than becoming preoccupied by one member's story. They observe the therapist glancing round to see how everyone is being affected by what is being said, and focusing on helping them to change what they do with each other" (Byng-Hall, 2001, page 33). In couple therapy, each member not only wants his or her story heard and acknowledged but may be highly vigilant about the veracity of the other person's story. And, each member is sensitive to whether or not the therapist believes his or her story since it may be contradictory to the other member's story. In individual therapy without the partner's perspective or words, the therapist can be seduced to believe truthfulness of the horrific treatment described by the individual. The experiences may be completely truthfully described, truthful with key missing elements- especially, the culpability of the teller in the dysfunction, or full of major distortions if not outright lies.

Early in therapy, Frieda told about how Cliff once screamed obscenities at her when she asked where he had been. He had been late getting home. She described how intimidating he was and how upset, scared, and hurt she was. The story reeked of injustice to her, and to the therapist... until Cliff told about a key element of the scenario that she had left out. He had been about fifteen minutes late because of a last minute chore at work that made him run late, along with bad traffic. Frieda had interrogated him about what he had really been doing for an hour and half through dinner. She had continued berating at him while he showered. He had worked a double shift and was exhausted from a long week of work. Unable to satisfy her, Cliff cut off the conversation and went to bed. He told her, "There's nothing else I can say to satisfy you. I'm sorry. I'm tired. I have to go to bed. I have an early teleconference meeting tomorrow with someone from the east coast (his office was in California). I'm sorry. We can talk about this tomorrow if you still need to." Cliff said, "She didn't tell you that. And then… Yes, I screamed and cursed at her... about half an hour after. Later when I had already gone to bed. Yeah, I swore at her. You know why? After I had fallen asleep... I was dead out and she had come into the bedroom and thrown a glass of water in my face! Hell yeah, I swore at that crazy bitch! What the fuck would you have done if you got a glass of cold water thrown in your face when you were deep asleep?" A quick glance over at Frieda was all the therapist needed to know that Cliff was telling the truth. She had left out revealing her provocative actions in order to maintain her victim status. During Frieda's initial phone conversation arranging for couple therapy, she had described Cliff as a vicious emotional brute and herself as the innocent victim. If this were individual therapy, the therapist would have had no reference that Frieda had a distorted sense of reality.

The individual with borderline personality disorder may not purposely lie, but can only focus on what is compelling him or her. His or her description of the events serves his or her relationship and life theme. Other information not relevant to confirming another betrayal, abandonment, or rejection experience recedes in consciousness. If the therapist accepts the individual's focus on the partner's misbehavior, the individual is validated as being a victim of others and is not be held responsible for toxic borderline behavior. While the individual may resist a more balanced depiction of the couple's dynamics, holding him or her responsible also empowers him or her to change the relationship and his or her life. By attributing the couple's problems primarily to the partner's behavior such a Cliff, the individual such as Frieda seeks to avoid dealing with stress, frustration, failure, and most of all, suffering. These are required for the individual to find the strength to endure the healing process and develop the skills to self-soothe and interact appropriately. It may have been impossible to have strength or skills sufficient at earlier periods of life to get needs met with omnipotent problematic intimates. The victim or helpless stance may have been developed to serve his or her ego in some convoluted developmentally essential manner. Letting go of the victim perspective, which requires the partner to seen as the oppressor, may be a significant challenge in therapy.

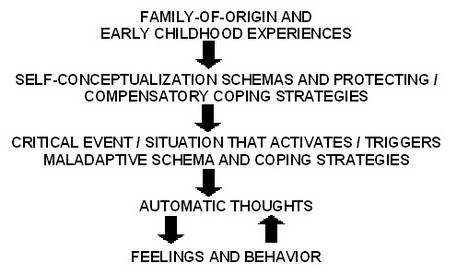

Most people hold core schemas about people and relationships "and they are assumed to be relatively stable, perhaps even becoming inflexible. Many schemas about relationships and the nature of couples' interactions are learned early in life from primary sources such as family-of-origin, cultural traditions and mores, mass media, and early dating and other relationship experiences. The 'models' of self in relation to other that have been described by attachment theorists appear to be forms of schemas that affect individuals' automatic thoughts and emotional responses to significant others (Johnson & Denton, 2002). In addition to the schemas that partners bring to a relationship, each spouse develops schemas specific to the current relationship" (Tilden and Dattilo, 2005, page 143). The schemas about relationships may be quite vague to very clear for individual. Nevertheless, the schemas alter how the individual perceives or interprets another person's behavior, underlying motivations, and feelings and thoughts about the individual. Tilden and Dattilo (2005, page 145) described individual case conceptualization from cognitive therapy using Figure 1 (J. Beck, 1995; d'Elia, 2000).

Early experiences that can affect attachment security influence the formation of schemas about self and coping strategies. Something happens that activates the schemas that trigger coping strategies. The individual has subsequent thoughts, feelings, and behaviors that may be productive to maladaptive. The individual with borderline personality disorder may direct attention and focus to eliminating the activating or triggering events. That is, that his or her partner should just stop provoking him or her. The individual's premise is that her or she would not have negative thoughts, feelings, and especially negative behaviors except for the "bad" actions by the partner. If the therapist does not recognize and challenge this conceptualization of the couple's dysfunction, then he or she will end up colluding with the individual with borderline personality disorder's misdirection of therapy towards changing only the partner's behavior. The partner will be encouraged to be "good" or stop negative or triggering behavior. This is doomed to perpetuate the dysfunction however because borderline sensitivity and vulnerability unpredictably makes almost anything can become a trigger.

The designation of a particular triggering injury/incident within a current timeframe may be misleading. The key critical injury or incidents may have occurred well before the relationship in the family-of-origin or childhood experiences. The therapist can be coerced to focusing only on the present and forget to examine the past- that is, looking for an original attachment trauma. "Identifying an attachment injury is critical to its working–through and integration into the relationship. Some couples may be particularly insightful into specific incidents that have marked the deterioration of levels of trust and intimacy in their relationship while others may not be particularly aware of how such events may be blocking accessibility and responsiveness" (Naaman et al., 2005, page 60). What constitutes an attachment injury is extremely subjective and dependent on embedded perceptions or schemas rather than some universally identified objective criteria. For example, when there is stress such as transition, attachment anxiety tends to be greater. "If the other partner is not perceived to be providing the needed care and support, feelings of abandonment ensue. Moreover, if these feelings cannot be discussed and dealt with in the relationship, they remain to undermine the trust and security of the relationship and may lead to abandonment or betrayal in times of change when attachment needs are heightened (e.g., childbirth, cancer diagnosis, and miscarriage) as well as to classical infidelity (Johnson & Whiffen, 1999)" (Naaman et al., 2005, page 60). The healing discussion needs to look beyond the partner's actions to also examine the original attachment injury that creates the vulnerability to recurrent attachment injuries.

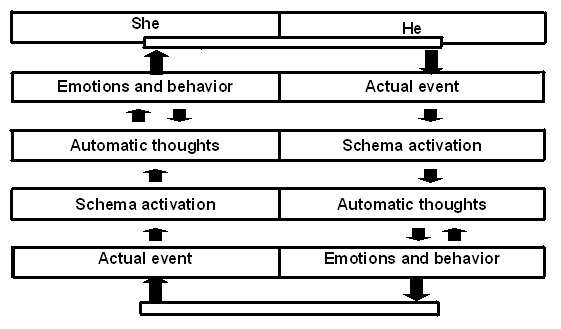

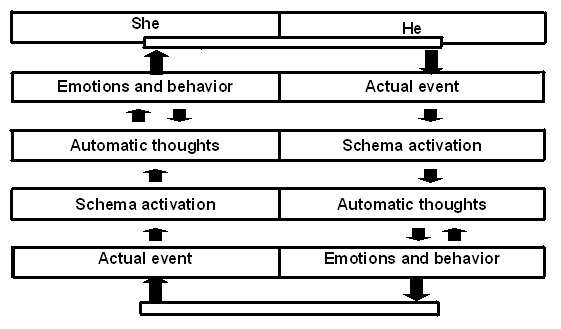

In couple therapy, the individual with borderline personality disorder often will ignore his or her vulnerability and be adamant that the partner's betrayal, abandonment, and rejection are the key problems in the relationship. Any apparent hesitancy on the part of the therapist to fully accept his or her rendition of the couple's dynamics may be experienced as betrayal- the implicit therapeutic contract to support him or her; as abandonment- the therapist not joining his or her side; and as rejection- the therapist rejecting his or her pain and reality. If the therapist seems to give credence to the partner's description of his or her attempts to provide caring contractual compliance, intimacy, and acceptance, the individual may feel betrayed, abandoned, and rejected again. The task of therapy is to nevertheless challenge the entrenched schemas effectively. While the individual with borderline personality disorder may try to force both the partner and the therapist to accept his or her interpretations and perceptions, the therapist must create new experiences in therapy and in the relationship that offer the possibility that schemas may be altered. Tilden & Dattilo (2005, page 152) use the following graphic to suggest a more balanced conceptualization of the relationship issues that involves both partner's processes and contributions.

By focusing on both members' processes and linking them together, the therapist alters the basic models that they may present. In the above model, the heterosexual couple functions in a mutually cyclical manner. At any given point, something happens- the actual event that activates one of the member's schema or perceptions. This prompts automatic thoughts from internalized expectations that lead to emotions and behavior. The behavior becomes the trigger- the actual event that activates the other member's schema. That member cycles through his or her version of the same process to create another trigger- another actual event that re-ignites or amplifies the process again with the first member. The cycle continues through mutual emotional relational confirmation bias unless one of the members can interrupt his or her process. Neither the partner nor the individual with borderline personality disorder remain the designated "bad" guy. Instead both members are identified as contributing to and perpetuating the relationship dynamics.

This process needs to be identified and accepted first. Therapy first should explore what happens and how it happens. Only then can the therapist proceed to examine in greater depth why it happens- that is, how the schema developed. Such depth work may not be productive without first revealing the couple's process. Therapy proceeds to examine any family-of-origin or other issues that created the schemas and automatic thoughts for each member. It is in this examination, that the therapist can uncover the roots of borderline personality schema among other factors. The therapist should also be wary of being too "fair" and holding both member's contributions to be exactly equal to the relationship dysfunction. When examining the underlying schemas, attachment trauma and the borderline personality will almost be more compelling contributors to relationship dysfunction than many other factors. In that couple's situation, the individual with borderline personality disorder is "more" the negative cause of problems. While the therapist may try to be therapeutically politically correct, he or she should direct greater clinical attention to the borderline issues. The art of therapy would be how to do so while dealing with borderline sensitivity.