12. Personality Disorders - RonaldMah

Ronald Mah, M.A., Ph.D.

Licensed Marriage & Family Therapist,

Consultant/Trainer/Author

Main menu:

12. Personality Disorders

Therapist Resources > Therapy Books > Opening the Can of Worms-Cple

Opening the Can of Worms, Complications in Couples and Couple Therapy

Chapter 12: PERSONALITY DISORDERS

by Ronald Mah

Gutman et al. (2006) cited studies that the "presence of a personality disorder was associated with increased likelihood of separation or divorce… and increases in marital problems" (page 1276). With increases in personality disorder symptoms, family functioning declines. "In fact, the total number of the patient's personality disorder symptoms was the strongest predictor of patient-reported family functioning, beyond the association between family functioning and the patient's depression, Axis I pathology, or aspects of general personality." Personality disorder symptoms in terms of the general level of functioning and particularly communication affect relationship interactions. The three personality disorder clusters are: Cluster A- odd or eccentric (Paranoid, Schizoid, and Schizotypal), Cluster B- dramatic, emotional, or erratic (Antisocial, Borderline, Histrionic, and Narcissistic), and Cluster C- anxious or fearful (Avoidant, Dependent, and Obsessive-Compulsive). "Personality disorder symptoms were found to be related to family functioning, both in terms of general level of functioning and communication in particular. This result extended to both the overall symptom count (i.e., across all disorders) and within each of the personality disorder clusters, with the exception of the association between Cluster A and B and general family functioning. Though these effects were small, they were consistent. Moreover, Cluster C and total number of personality disorder diagnoses were also significantly related to the communication aspect of family functioning. The general pattern of results is consistent with those found by Daley and colleagues (2000), who found that personality disorder symptoms were related to different indices of romantic relationship dysfunction. In their analyses, they assessed the individual contributions of each cluster to the relationship while controlling for the effects of other clusters; they found that Cluster B was related to most variables, whereas Cluster A was only related to some, and Cluster C did not appear to make any independent contributions" (Gutman, 2006, page 1282)

Personality disorders can affect people's relationships in a variety of ways. "The interpersonal relationship may be impacted by the suspiciousness of the paranoid patient, the detachment of the schizoid patient, or the emotional instability of the borderline patient, but for every personality disorder there is at least one diagnostic criterion that assesses how the patient interacts with others (DSMIV-TR; American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2000) (page 1275-76). It may be that individuals with a mental disorder including (perhaps, especially) a personality disorder have significantly greater problems functioning successfully in intimate relationships as opposed to other social relationships (page 1285). Jansson et al. (2008, page 172) found that individuals with personality disorders have "…poorer outcome of drug use treatment, including compliance problems, attrition, and relapse after treatment. Caseworkers have found that patients with personality disorders are globally more difficult to manage, chaotic, and aggressive, less engaged in treatment, and less frequently compliant with care plans. However, personality disorders are also associated with adjustment problems, both in terms of general psychosocial adjustment and psychiatric symptoms. Anxiety disorders are less likely to remit with co-morbid personality disorder. A recent meta-analysis of the impact of categorical personality disorders on outcome of treatment for depression showed that personality disorders were associated with a significant increase in the risk for poor outcome. A study of substance abusing patients showed that patients with more personality disorders were found to be more symptomatic at 6 years follow-up".

In couples with challenges for one or both partners, consistent and cooperative self-care serves the individual and the relationship. When the challenged partner is not compliant or is inconsistent with treatment for any issue (medical/physical, economic, vocational, emotional, spiritual, and so forth), the other partner becomes likely to doubt whether the challenged partner is even willing or invested in change. The non-challenged partner often suffers along with the challenged partner and feels frustrated when change is slow or compromised. Without direct power and control over the challenged partner's recovery or health process, anger and resentment can develop. Personality disorders are especially challenging for partners to understand. The individual with a personality disorder often does not experience his or her life perspective, emotions, or thought processes as problematic or erroneous. As a result, his or her communications or behaviors seem appropriately instinctive and logical. His or her partner's reaction or judgment/evaluation of the communications and behaviors are illogical! Only when and if the other partner's responses including boundaries and demands threaten the challenged partner's well-being, needs, or relationship might he or she consider a need to change. Cole for example, experiences his emotional relationship process as appropriate. It's Molly's angry reaction that threatens them being able to maintain the relationship. If Molly accepted his emotional and relationship behaviors, Cole would be fine continuing to function per the… his status quo. This is significantly different from someone who is depressed, anxious, distressed, or in despair. That person finds his or her emotional, spiritual, and/or intellectual experience uncomfortable. Cole might become depressed or anxious because of relationship conflict and only then consider changes that he would have never otherwise thought personally necessary. Cole had not agreed to couple therapy because he was unhappy per se, he had come because Molly was making him unhappy! As a result, his initial request for the therapist was to fix her, convince her that he was right, and that she was wrong.

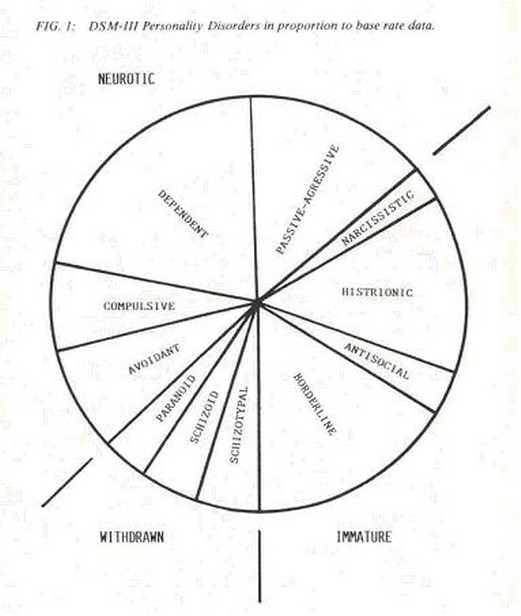

The three personality disorder clusters have been re-conceptualized from DSM-III and DSM-IV. DSM-V will have other modifications when it becomes official. The following compares DSM-III and DSM-IV (Vincent, 1987, page 36, APA, 1994, page 629-30):

withdrawn character (DSM-III's odd and eccentric category; DSM IV cluster A): paranoid, schizoid, schizotypal personality disorders.immature character (DSM-III's dramatic, emotional and erratic category; DSM IV cluster B: histrionic, narcissistic, antisocial, and borderline disorders.neurotic character (DSM-III's anxious or fearful category; DSM IV cluster C: avoidant, dependent, obsessive-compulsive personality disorders.

Passive-aggressive personality disorder was included in DSM-III's anxious or fearful category. It is classified under Personality Disorder, Not Otherwise Specified (NOS) in DSM-IV, as it is not included within one of the three clusters: A, B, or C. Vincent (1987, page 36-37) considers passive-aggressive personality as the bridge between the neurotic character and immature character. In addition, "…avoidant personality can be seen a bridge between the neurotic character and the withdrawn character. The avoidant personality combines the sensitivity, mild paranoia and people avoidance similar to low grade paranoid individuals with the anxiety of a classic neurotic character such as the compulsive personality… The third proposed personality bridge is borderline personality disorder; which is a bridge between the withdrawn character and the immature character. This draws support from literature which shows that borderline individuals are apt to be a combination of the emotional liability of a hysteric coupled with the fear of people of a schizoid individual."

The graphic below (Vincent, 1987, page 39) allows the therapist to see a continuum of dysfunction. Often a specific diagnosis may not fit a client. The graph however may be misleading because they seem to indicate distinct boundaries among personality disorder that may not be appropriate.

Olivia's boyfriend brought her into couple therapy in a last ditch attempt to save the relationship. Olivia immediately dominated the therapy. She went on and on about herself and how she functioned. She told the therapist about the process and theory of couple therapy. She was a licensed clinical Psychologist who was twice divorced. She explained why her relationships didn't work. She said she was too strong a woman for most men to handle. Interestingly, she didn't give that much information about why her boyfriend didn't work out in the relationship. While criticizing him, she still focused primarily on himself. Her language and mannerisms were flamboyant, while her articulation was surprising very sophisticated. When her boyfriend tried to explain his concerns, Olivia interrupted and corrected him. He could barely get a word in. The therapist could barely get a word in! Olivia had characterological qualities that defied a singular personality diagnosis. She was very intelligent and articulate about the nuances of her life, relationship, and profession. Over several sessions, Olivia showed narcissistic personality disorder behaviors where she could be extremely charming but be ignited when challenged. Narcissistic behaviors to annihilate intellectual or vocational competitors are classic symptoms. She could make withering remarks at her boyfriend's expense. However, she did not challenge the therapist's credentials however as many narcissists often do. As opposed to many narcissists who can interact socially and focus attention on others, she had difficult turning herself off. She was not charming or interesting as a person. She talked about therapy but was not available for an intellectual exchange with the therapist.

In some ways, she was unlike a narcissist but more like a histrionic personality. Narcissists tend to keep themselves preeminent when there is the potential of competition, but can tolerate other's presentations and show genuine interest as long as there is no threat. They can offer very compassionate care and advice, and thus be very likeable while sharing intimacies. Narcissists can be very engaging and intellectually stimulating. They can build strong reciprocal social relationships. However, Olivia had histrionic symptoms in being unable to tolerate attention turning from her at all. She needed to maintain a one-sided social relationship with herself as the object of attention. If she could not keep the attention on herself, she "turned off" and scanned the room to see if she could draw the attention of someone. Her presentation of histrionic qualities differed however from classic histrionic individuals in having more quality and substance than usual. She was histrionically needy for attention, but didn't present with shallow histrionics but with more admirable substance. However, her histrionic qualities did not allow her to give up the stage. Olivia did turn on and try to destroy others like other narcissists when she felt challenged. She did this to her boyfriend. She did this to the therapist. Needless to say, her intimate relationships were highly volatile and unstable.

The therapist would be unable to put a person such as Olivia into one personality disorder diagnosis versus another. She had qualities of at least two disorders; and arguably a third disorder- borderline personality disorder. The therapist did not come to the diagnoses from the plentiful personal information given by Olivia. It was by inference of two previous marriages and other failed relationships along with the in-session experiences that the therapist determined that she had long-term symptoms characteristic of personality disorders. Olivia did not behave within anticipated or normal interpersonal and therapeutic models of social interaction. Her behaviors harmed the couple's relationship and disrupted the desired therapeutic rapport. Personality disorders are enduring patterns of inner experience and behavior that deviate markedly from the standard expectations of an individual's culture. The patterns are pervasive and inflexible. Try as much as possible, the therapist could not get Olivia to respond differently. Personality disorders are usually considered to have an onset in adolescents or early adulthood, are stable over time, and lead to distress or impairment. Gregory Lester (2011), expert consultant on personality disorders discussed how children as young as five years old can fulfill every DSM-IV criteria for a personality disorder diagnosis. In this clinical situation, Olivia did not stay in therapy long enough to investigate the genesis of her process. Her boyfriend got frustrated and gave up on the therapy and the relationship. It is questionable that Olivia would have been available for such in-depth exploration. Her narcissistic and histrionic behaviors may have been developed to avoid experiencing her deeper issues. Talking about topics she was expert in and otherwise drawing attention to herself, but away from uncomfortable parts served to maintain her psychic stability. The therapist should be aware of potential cross-cultural situations, where a pattern apparently odd to others may be consistent rather than deviating from the expectations of the individual's original culture. For Olivia, her pattern may have been consistent with her family or cultural dynamics or both. Olivia's children grew up with her behavior and did not know any other mother. Her boyfriend had remarked that with Olivia and her kids and with Olivia's siblings and parents, everyone either acted the same way or did not seem to recognize how odd they were. Olivia's boyfriend said if it weren't for confirmation from the few individuals who had married into or were dating someone in the family, he would have thought something was wrong with him. After all, Olivia was quite articulate in telling him it was him! Olivia's pattern that was consistent with her family patterns led to marked distress or impairment for others such as a new boyfriend or someone else in a new cultural context.

The therapist is aware that certain common family dynamics and experiences often lead to the development of personality disorders. The lack of appropriate mirroring, of consistent nurturing, and violations of the emotional boundaries that are hypothesized to cause personality disorders can exist all over the world. There may also be common cultural experiences that lead to personality patterns that would be similar to or considered by professionals to be personality disorders in a new cultural context. In some societies, these dynamics exist for large groups of people rather than just in specific families. It also may be that certain cultural experiences from social/historical circumstances tend some individuals toward personality disorders. For example, the therapist should consider societies and communities where political or spiritual leadership presents itself as an idealized loving benevolent parent ("the great father") but functions in inconsistent, arbitrary, and punitive ways. Such societies blame oppressed people for transgressions, punishes them severely, physically and emotionally abandoning (isolating, imprisoning for example); and then rehabilitates them back to beloved status... only to repeat the cycle over and over. This process across a larger totalitarian society is highly comparable to dysfunctional or abusive family dynamics that can lead to personality disorders in individuals. The therapist may consider the conjunction of individual/family experiences and social/cultural models that accentuate or intensify patterns otherwise not considered clinically or diagnostically significant to meet criteria for a DSM diagnosis.

Potential cross-cultural considerations should alert the therapist to the probability that an individual with a characterological diagnosis or a rigid cultural pattern will not only assert their issues with his/her partner, but will also assert it with the therapist. Just as a partner may be perceived as the new abuser, betrayer, or controller, the therapist by virtue of his or her role may be similarly viewed. Transition of a pattern can be from the family-of-origin to the new couple and the partner, from another society or community to a new country and new authority figures and peers, and from either to the therapy room and the therapist. Authoritarian male (or female) and submissive female (or male) family role models and/or cultural, social, and/or religious models of patriarchal dominance and matriarchal deference may contribute to and be embedded in personality disorders that can manifest with the therapist. And manifest differentially depending on whether the therapist is male or female and upon his or her theoretical orientation and clinical style. The therapist must not naively consider him or herself immune from the projective process or transference of a personality-disordered individual. The therapist should anticipate the probability of being drawn into the personality disorder unreality and take appropriate steps to avoid duplicating the process non-therapeutically. On the other hand, the therapist may be able to- and perhaps, need to join the personality disorder process to interact therapeutically to counter dysfunctional behaviors.