4. All Therapy is About DepAnxiety - RonaldMah

Ronald Mah, M.A., Ph.D.

Licensed Marriage & Family Therapist,

Consultant/Trainer/Author

Main menu:

4. All Therapy is About DepAnxiety

Therapist Resources > Therapy Books > I Don't You Don't, DepAnxiety-Cple

I Don't… You Don't… It Don't Matter, Depression and Anxiety in Couples and Couple Therapy

Chapter 4: ALL THERAPY IS ABOUT DEPRESSION AND ANXIETY

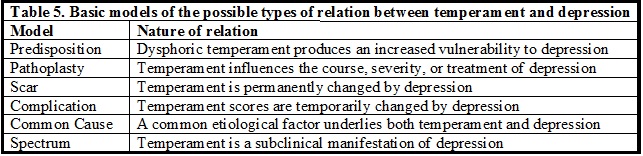

Grace among many other clients enter therapy feeling and thinking, "I don't matter… there's nothing I can do about it… and I'm vulnerable to harm… and I don't know when harm will come." A person comes to therapy to address a fundamental need to feel valued and gain power and control intrapsychically, emotionally, psychologically, spiritually, intellectually, in life, and with others, especially intimate others: partners, children, and family. A client often presents with depression from failures, inconsistency, and doubts to gain feelings of self-esteem and mastery within self, within relationships, and in the world. A client often presents with anxiety from incompetence, lack of control and power, and being devoid of protection from assaults to self-esteem and mastery within self, within relationships, and in the world. Counseling or problem solving may become a part of therapist-client work. However, therapy may be conceptualized as going beyond counseling for problems and delving into the deeper emotional and psychological issues that waylay simple problem solving. These deeper issues block simple and even obvious problem solving because of unresolved needs, trauma, injury, and other complexities of psychic energy. The futility of not being able to access and activate simple solutions creates depression. The futility of not being able to adequately protect oneself from harm and tolerate life's inherent ambiguities and vulnerabilities create anxiety. "…depression and anxiety have been shown to be substantially overlapping concepts that are highly intercorrelated both in self-reports and in clinician's ratings, and that are strongly comorbid at the diagnostic level… (Watson and Clark, 1995, page 354). As a result, all therapy beyond counseling for problem solving is about one issue- that of a conceptually unified experience of anxiety and depression. While clients present many different concerns or problems in therapy, depression and anxiety are usually central issues. "…although depressed individuals do tend to correspond to the classic melancholic type (i.e. high Negative/low Positive Temperament), this pattern is not unique to depression but characterizes other types of psychopathology as well (Watson and Clark, 1995, page 360). The following table gives consideration to how inherent (natural in-born temperament) characteristics can affect or are affected by depression.

These can be seen as three pairs of models. The Predisposition model postulates that being born with a "dysphoric temperament (i.e. being high in Negative Temperament and/or low in Positive Temperament) increases the likelihood that a person eventually will experience a major depressive episode." In the extreme case relative to a couple, one partner may accuse the other of being "born depressed" and absolve him or herself from any causal contributions to the partner's depression. By itself, this model also basically dismisses attachment and other developmental influences on the person's depression. However, if one is seen as having a temperament that creates an increased vulnerability to depression, it becomes incumbent upon the primary caregivers to mitigate the vulnerability with excellent parenting. It implies that the family-of-origin and social/cultural influences had faced difficult odds above and beyond normal caregiving challenges. This may be a difficult model for the couple to hold as it significantly limits the partners (and the therapist) towards addressing only current depression. The Pathoplasty model says that once depression has developed, temperament interacts with it to influence its severity, course, or response to treatment. This model may be useful for the couple to alleviate depression and to respond to its effects on the couple's relationship. By understanding a person's contribution to depression and their partners' interactions, therapy can direct them to more productive responses.

The Scar and Complication models reverses the premise that temperament causes depression and asserts that depression influences temperament, either transiently or permanently. The Scar model sees an episode of depression leading to fundamental changes in personality. The person becomes and persists in being significantly more dysphoric than before. This model offers no real hope of improving negative temperament and would leave the couple with only the option to learn to live with it. The Complication model holds that one's temperament will revert to pre-depression levels. This is much more hopeful for an individual and for the couple. The third pair of models see temperament and depression reflecting one underlying process or etiological factor- neither clearly causing the other. The Common Cause model posits that a common etiological factor gives rise to both depression and temperament. This model could prompt the couple and therapy to look for the common factor- for example in the attachment experiences, cultural models, substance use, or the family-of-origin. The Spectrum model proposes in a continuum of functioning, depression essentially represents extreme levels of dysphoric temperament- "the traditional melancholic pattern can be viewed as a subclincial manifestation of depression" (Watson and Clark, 1995, page 361). These models are not mutually exclusive. Of concern for the therapist is whether the partners believe in a model that is problematic for therapeutic progress for the couple's relationship. Therapy may need to present a model viable for growth and change that simultaneously resonates with the partners' experience and views.

The therapist may need to assess for depression and anxiety in one or both partners in the couple. The sub-clinical diagnoses of being upset, nervous, sad, and so forth may be relevant. An individual presenting so may be considered as reacting or responding normally to the stress of life and/or of the couple's issues. A Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) diagnosis of Adjustment Disorder with Depressed, Anxiety, or Mixed Emotional Features (APA, 1994) may be appropriate if a person's reaction of depression and/or anxiety to an identifiable psychosocial stressor is considered overly intense or dysfunctional DSM-V has only minor changes to the diagnostic criteria- none relevant to this discussion (APA, 2013) The therapist should question the partners if there is an identifiable stressor that has triggered the depression or anxiety. The stressor itself or how the individual and/or the partner or couple handled the stress may be where the therapeutic focus will find fruition.

Julia and Carter came to therapy with complaints about their intimacy, specifically their sexual intimacy. In the course of early therapy, the therapist began to suspect that Julia was depressed. When asked about how she felt and how she was doing, Julia replied rather blandly, "Ok, I guess." When asked how she seemed to him, Carter revealed, "She's always been a happy upbeat person. But she's been kinda dragging, moody, and negative the last two or three months." The therapist recognized that the behavior or mood was not chronic and probably had a specific beginning time frame. When the therapist asked what had been going on about two or three months or so, they explained that Julia had been given notice that her position at her company might be terminated. She had worked there for 10 years and was close to a lot of her co-workers. Julia was told that the company was going to take a month review its structure, workforce, and strategies for dealing with the economic downturn and would let her (and about 10 other workers) know if they could keep their jobs or if their positions would be eliminated. They gave notice up to a month ahead in case they needed to let some or all of them go in the process of the evaluation. Making it to the end of the month meant you would be retained. Julia had been relieved that they decided to keep her. She didn't have to take a pay cut, but had her hours adjusted some and took on some more responsibilities. And none of her good friends were eliminated either.

As the therapist continued asking her about her almost losing her job, Carter interrupted, "Why we talking about this? Julia didn't lose a day's work. We didn't have to cut back financially. So, what's the big deal?" Julia sighed, "That's just it. Carter just didn't get it." When the therapist asked what Carter didn't get, Julia replied, "It was so scary. It was like my family… divorcing me or something! I was going to work every day not knowing if the ax would fall and chop my head off! I never felt so helpless. There was nothing I could do. It was all out of my control." Carter said, "That's right… there was nothing you could do but wait. So you waited… I waited… and it turned out ok. What's the big deal? There wasn't any point worrying about something you had no control over. There wasn't any point trying to figure out or solve a problem that we didn't have yet… or might never have… and that we ended up not having!" Julia said, "That was his attitude the whole time. Just 'whatever.' 'Don't worry about it' like I could NOT worry about it. He didn't get it then… and he still doesn't get it now." Carter snapped, "What the hell is there to get!? Everything turned out fine! And what's this got to do with you not wanting to have sex?"

The therapist recognized that Julia's lack of sexual energy and interest probably came from her depression and anxiety. The depression and anxiety was partly a result of the stress of potentially losing her job a few months ago. The stress of waiting to hear about her job was difficult. It made her feel helpless, anxious, and depressed… a significant but reasonable amount. However, it was Carter's failure to empathize and relate to her depression and anxiety that was the additional stress that took her over the top. Helplessness about job security was nothing compared to feeling helpless about getting Carter to understand and relate to her feelings. Carter's classic male problem solving mentality, ability to compartmentalize stress, deny his own anxiety, and avoid facing her stress that he could not problem solve readily kept him from showing the compassion that she needed. It felt like a fundamental betrayal of the couple's reciprocal nurturing contract to Julia. By examining and validating her emotional style and need for validation and his cognitive problem solving style, therapy sought to help Julia and Carter identify the underlying origin (stressor) for Julia's subsequent depression and subsequent loss of desire for sexual intimacy.

While the process of therapy for Julia and Carter involved other issues and challenges, discovering that Julia's depression was not characteristic of her and then, ascertaining its origin defined therapy's starting place and strategic direction. Watson and Clark (1995) summarized four types of humours that correspond to different personality types. The Sanguine temperament personality (which Julia had) is fairly extroverted. Individuals with a sanguine temperament tend to enjoy socializing, making new friends, and be boisterous. Usually creative and sometimes daydreamers, they also need some alone time. Sanguine personalities can also be very sensitive, compassionate and thoughtful. They may struggle following all the way through on tasks, may have timeliness issues, be forgetful, and sometimes a little sarcastic. They can lose interest quickly when something is not engaging or fun anymore. Definitely people persons, they are talkative and not shy. They are desirable friends- often lifelong friends. Choleric people are do-ers, which is more Carter's personality. Possessing a lot of ambition, energy, and passion, they to instill it in others. They can dominate people of other temperaments, especially phlegmatic types. Many great charismatic military and political figures had choleric personalities, liking to be leaders and in charge. Phlegmatic personalities tend to be self-content, kind, very accepting, and affectionate. Very receptive and shy, they often prefer stability to uncertainty and change. Since they are very consistent, relaxed, rational, curious, and observant, they make them good administrators. However they can also be very passive-aggressive. Julia had some phlegmatic tendencies, hence her passive-aggressive withholding of sex from Carter as retaliation for him emotionally abandoning her.

In identifying depressive qualities, the therapist should consider if they are characteristic of Sanguine, Choleric, and Phlegmatic personalities' moods or behaviors. As a result, if therapeutic assessment finds one of these three personalities co-existing with depressive qualities, then the therapist should strongly consider if there was a psychosocial stressor that has triggered the depression (an adjustment disorder diagnosis if using DSM terminology). Julia was normally happy and upbeat- a classic sanguine personality, so her droopy energy was identifiably different and a cue that something had disrupted her. On the other hand, the melancholic personality may show depressive qualities with or without an identifiable psycho-social stressor. Thoughtful ponderers have a melancholic disposition. They can be often very considerate and prone to worrying, for example about being late. Melancholics can be highly creative and can become preoccupied with the negativity around them. They can be perfectionists. Often self-reliant and independent, they can get so absorbed they can forget about others. The DSM-IV diagnosis that is compatible with melancholic personality is Dysthymic Disorder, which is now included in the DSM-V diagnosis of persistent depressive disorder (APA, 2013). As opposed to stress triggered depression, it is a more chronic presence of two years or more of a depressed mood. Dysthymia is more pervasive than depression that is triggered by an identifiable stressor. It persists for a longer time frame. While pervasive, it is usually not debilitating. The individual tends to be able to functional reasonably adequately to maintain school, work, hygiene, home life, and most relationships. Negative mood, irritability, difficulty maintaining positive mood or joy in life and relationships, low energy, physical, emotional, psychological, intellectual, and spirit fatigue, poor concentration, distractibility, and a general sense of doom or helpless are common characteristics.

Watson and Clark (1995, page 352-53) give a description of Negative Temperament that would fit for Dysthymic Disorder. "…those high in Negative Temperament are prone to experience various negative moods. In addition to this marked affected distress, however, high scorers on this dimension tend to be introspective and ruminative; perhaps as a result, they are prone to psychosomatic complaints. They also have a negativistic cognitive/explanatory style and focus differentially on undesirable and problematic aspects of themselves, other people, and the world in general. Consequently, they have a negative self-view and tend to be highly dissatisfied. Finally, they report relatively high levels of stress and appear to cope poorly with this stress. In contrast, individuals who are low in Negative Temperament are satisfied with life and themselves, and view the world as essentially benign. They report few problems, low levels of negative mood, and little stress in their lives (McCrae and Costa, 1987; Watson and Clark, 1984; Watson et al., 1994)… Positive Affect… low scorers lack… confidence, energy, and enthusiasm. They tend to be reserved and socially aloof, and they avoid intense experiences. Generally speaking, they are more hesitant to engage their environment actively (Tellegen, 1985; Watson et al., 1994)… these two dispositions are largely independent of one another… individuals who are high in both Negative and Positive Temperament can be identified with the classic 'choleric' type, whereas those who are low on both dimensions can be characterized as 'phlegmatic'. Next, those who are high in Positive Temperament and low in Negative Temperament clearly correspond to the traditional 'sanguine' type. Finally, those who are high in Negative Temperament and low in Positive Temperament can be classified as 'melancholic'… depressed individuals should tend to be high in Negative Temperament and low in Positive Temperament (Watson and Clark, 1995, page 353).

The individual with dysthymia may have formulative, historical, and persistent doubts of mattering to others or of ever having mastery, power, or control in the world in general. An individual with dysthymic tendencies carries them into all activities and experiences of his or her life, including the intimate couple's relationship. Predisposed from earlier experiences or triggered by relationship or life stresses in the partnership, depression as well as anxiety may become intrinsic to marriage and coupling. The distinctions between Dysthymic Disorder and Major Depression previously made in DSM-IV may be an issue of degree or extremity on a continuum or have some important qualitative differences. While Major Depression as well as Dysthymic Disorder may have elements of biological predisposition and significant problematic life experiences, the intensity of dysphoric emotions and interferences with negative life functioning in Major Depression were presumed in DSM-IV to bring greater challenge to individual and his or her relationship. Although, the disorders have been merged in DSM-V, subjective severity or duration can make strong demands on a relationship. During an episode of depression, the non-depressed partner may give support and comfort. This would have a positive effect on the depressed person and improve their relationship. However, chronic depression may create partner hostility and his or her withdrawing from the relationship. Any individual or relationship vulnerability may be triggered or intensified by the burdens of chronic depression. As a result chronic depression may create worsen couple's security more than discrete episodes of depression.

"Chronic depression, particularly among women, may be corrosive to marital relations. Dysphoric wives tend to solicit, receive, and provide support in a negative manner when interacting with their husbands, which increases their marital distress (Davila, Bradbury, Cohan, & Tochluk, 1997). Alternatively, the husband's attachment insecurity may be a source of conflict which then exacerbates his wife's depression. The latter hypothesis is consistent with the marital discord model of depression (Beach, Sandeen, & O'Leary, 1990), particularly as it applies to chronically dysphoric individuals (Beach & O'Leary, 1993). The husband's insecurity and the wife's chronic depression likely create a negative feedback loop that maintains the distress of both partners. Marital therapy is an effective treatment for depression when marital distress also is present (e.g., Jacobson, Dobson, Fruzzetti, Schmaling, & Salusky, 1991). Our research suggests that marital therapy may be especially helpful when the wife's depression is chronic. Marital therapy that focuses on repairing the attachment bond (emotionally focused couple therapy, EFT; Johnson, 1996) may be particularly effective for these couples (Whiffen & Johnson, 1998)" (Whiffen, 2001, page 587). An individual may have Major Depression or history of Major Depressive episodes simultaneous or prior to joining in a romantic committed relationship, or develop Major Depression during the relationship. It would be inappropriate to assume the degree and quality of triggering conditions and experiences in couples in general. Individual examination and determination of each individual and each couple would be necessary to begin to guess at how Major Depression would have arisen. Depression and anxiety or other psychological disorders may be a consequence of life, individual, or relationship stress, a cause of stress in the couple, or a mutually problematic cycle among partners and the relationship.

"Whisman (1999) examined the association between marital dissatisfaction and 12-month prevalence rates of common Axis I psychiatric disorders in married respondents from the National Comorbidity Survey (Kessler et al., 1994). Results indicated that spouses with any disorder, any mood disorder, any anxiety disorder, and any substance-use disorder reported significantly greater marital dissatisfaction than spouses without the corresponding groupings of disorders. In relation to specific disorders, results suggested that greater marital dissatisfaction was associated with 7 of 12 specific disorders for women (with the largest associations obtained for posttraumatic stress disorder, dysthymic disorder, and major depression) and 3 of 13 specific disorders for men (dysthymic disorder, major depression, and alcohol dependence)" (Goldfarb, 2005, page 110). Bryne, et al. (2004) looked at couple therapy to treat Panic Attacks with Agoraphobia (PDA). While in vivo treatment, including systematic desensitization often shows significant efficacy in reducing anxiety and panic attacks, there are may be high frequency of dropping out and relapse. From a cognitive behavioural perspective, "spouses can make a significant contribution to treatment, by ceasing to inadvertently reinforce agoraphobia through excessive caretaking and actively reinforcing the development of anxiety management skills and the completion of exposure-based homework assignments (Oatley and Hodgson, 1987). This is the rationale for spouse-assisted therapy (page 106-07). This consideration therefore presents simultaneously the possibility of the influence of the couple's relationship on the development of PDA. Systemic perspectives propose that PDA develops through a circular homeostatic pattern of behavior in the person with the panic attacks, where he or she becomes dependent on the partner's caretaking. Each partner has gains in the relationship. The caretaker partner is able to "avoid addressing anxiety-provoking personal issues such as low self-esteem or fear of psychological and sexual intimacy. The person with PDA is protected from having to face the challenges of individuation" (page 107).

Self-esteem, intimacy and difficulty separating oneself from others may come from deep issues from the family-of-origin that have never been resolved. This apparent dysfunction may create a psychic mutuality that initially attracted the partners to together. If this is the case, then if the anxious partner with panic attacks improves, it would challenge the equilibrium of the system. The care-giving partner would no longer have his or her role to support the now non-agoraphobic partner. Individual resolution of previously unresolved issues such as low self-esteem, fear of intimacy and individuation could cause the previously non-symptomatic "healthy" partner to deteriorate without a clear role in the relationship. "This in turn may lead the apparently healthy partner to undermine their agoraphobic partner's recovery. This aspect of the systemic formulation of PDA provides a further rationale for including both members of the couple in marital therapy for the effective and lasting treatment of PDA" (page 107). Systemic theory would propose this potential relationship deterioration when there occurs any significant change positively or negatively in mental health or functioning for a partner in a couple. Bryne et al. found that non-distressed couples got greater benefit from exposure-based treatment than distressed couples. Partner-assisted exposure therapy led to symptomatic improvement for 23-45% of cases. This was as effective as individual exposure therapy and female friend-assisted exposure therapy, and more effective than partner-assisted problem solving therapy and marital therapy. Partner-assisted exposure therapy effectiveness is believed be enhanced when combined with cognitive therapy that challenges beliefs underlying avoidant behavior, and couples communication training which empowers them to deal with relationship issues. Not surprising, couples-based treatment is more beneficial to relationship quality than individually based treatments. "It may be that while exposure is a critical aspect of all effective therapeutic approaches to PDA, couple-focused interventions may enhance maintenance of treatment gains by facilitating interactions that positively reinforce and perpetuate exposure attempts" (Bryne, et al., 2004, page 119).

Depression and anxiety in all forms are often intrinsic to couple's difficulties. Depression is usually examined and treated as an intrapsychic phenomenon within an individual. As a result, theories regarding the causes or origins of depression tend to focus on various different aspects in individuals. However, "through self-report questionnaires and clinical interviews… support a bidirectional relationship between depression and marital quality. Coyne et al. (1987) indicated that depression in a spouse negatively affects marital quality, and in a separate study, Beach and O'Leary (1993) demonstrated that marital discord predicts later increases in depression symptoms. Physiological arousal associated with anger has been measured directly in Gottman's (1998) research, with results indicating that physiological arousal during high-conflict interactions is highly predictive of declines in marital satisfaction over a 3-year period (Levenson & Gottman, 1985) (Dehle and Weiss, 2002, page 329). As a result, therapist assessment in individual, couple, or family therapy should avoid looking at a depressed individual isolated from the important environmental and interpersonal circumstances that may create or influence anxiety and depression.