13 Reasons Miss Soc Cues- - RonaldMah

Ronald Mah, M.A., Ph.D.

Licensed Marriage & Family Therapist,

Consultant/Trainer/Author

Main menu:

13 Reasons Miss Soc Cues-

Therapist Resources > Therapy Articles

"Huh? What!?" 13 Reasons for Missing Social Cues

WHO IS THIS KID?

1. Startles unexpectedly2. Doesn’t understand what other kids wanted3. Anxious for no apparent reasons4. Confused5. Often speaks w/o inflection6. Avoids spontaneous social interactions7. Trouble sustaining a conversation8. Suddenly hits or pushes w/o apparent provocation9. Plays with toys over and over (ritualistic?)10. Cries inconsolably over small issues11. Frequent toileting accidents12. Problems with transitions13. Trouble making friends14. Often clingy with adults15. Takes disposed food from garbage cans to eat

The therapist, parents, and teacher developed this list of Jerry’s behaviors. His parents felt that Jerry would "grow out of it." His behavior however was not strictly developmental and would change with maturation. Teacher and therapist concurred that Jerry’s behaviors were probably indicative of other issues. Unfortunately avoidance and denial may be parental responses when professionals bring up potentially sensational issues. Schwartz-Watts (2005) examined early attempts at intervention with a 5-year-old later diagnosed with pervasive developmental disorder who eventually got into criminal problems as a teenager. “Each time the defendant attended a new school his teachers became aware of his impaired functioning and sent him for evaluation. His parents did not follow up with any treatments, although they were recommended,” (p.390). Jerry was showing behaviors and issues that predicted more serious problems later. Nevertheless, neither Aspergers Syndrome nor other key issues cause or is Jerry doomed to dysfunction. Support, and intervention, including therapy directed through identifying key etiological factors can mitigate potential struggles and negative outcomes.

Aspergers Syndrome #1- Rote Learning

Children develop relationships primarily through the interactive process of play. With greater verbal skills, conversation becomes critical to play. Aspergers Syndrome (AS) fundamentally affects communication, play, and relationships. Bauer (1996) notes that “Pragmatic, or conversational, language skills often are weak because of problems with turn-taking, a tendency to revert to areas of special interest or difficulty sustaining the ‘give and take’ of conversations… Some children with AS tend to be hyperverbal, not understanding that this interferes with their interactions with others and puts others off.” By middle-school, individuals with AS often got into annoying verbal sparring bouts trying “win.” Your Little Professor, an online resource, discusses the targeting of children with AS (referred to as “Aspies”) for bullying. “The reason is that Aspies fit the profile of a typical victim: a ‘loner’ who appears different from other children. Like hungry wolves that attack a limping sheep that can't keep up with the herd, the Aspie with his clumsy body language and poor social skills appears vulnerable and ripe for bullying…" (2008).

Social Cues

Characteristic of AS, Jerry missed social cues- especially non-verbal social cues, that are critical to interpersonal communication: facial cues including muscle tension or relaxation around the eyes and mouth, tilting, leaning, or nodding one’s head, and combinations of changes in breathing, expansive to very slight movements of the hands, arms, body, and legs. “Nonverbal communication is quite possibly the most important part of the communicative process, for researchers now know that our actual words carry far less meaning than nonverbal cues. For example, repeat many times the following sentence, emphasizing different words in the sentence each time you do so: 'I beat my spouse last night,'"(Long Beach City College Foundation, 2004). The words themselves carry many meanings, depending upon nonverbal cues- in the case, inflection.

Successful expressive and receptive communication are keys to intimacy, trust, relationships, and to social, academic, and vocational survival- issues that bring individuals of all ages to therapy. In “Body Language in Debating,” Mandic (2008) promotes 10 compelling non-verbal forms of communication applicable to day-to-day communications. Becoming non-verbally fluent, centered, grounded and flexible not only develops self-esteem, fluency and flexibility, but also enables better communication skills and relationships in life. Gordon and Fleisher (2002, p.84) described how an interviewee's truthfulness is determined by observing a multitude of non-verbal cues that mirror processes people intuitively use to determine honesty or deceptiveness in others communication. Poor interpretation of social cues may include inadequate presentation of social cues which intensifies problems.

REASONS INDIVIDUALS DON’T GET IT!

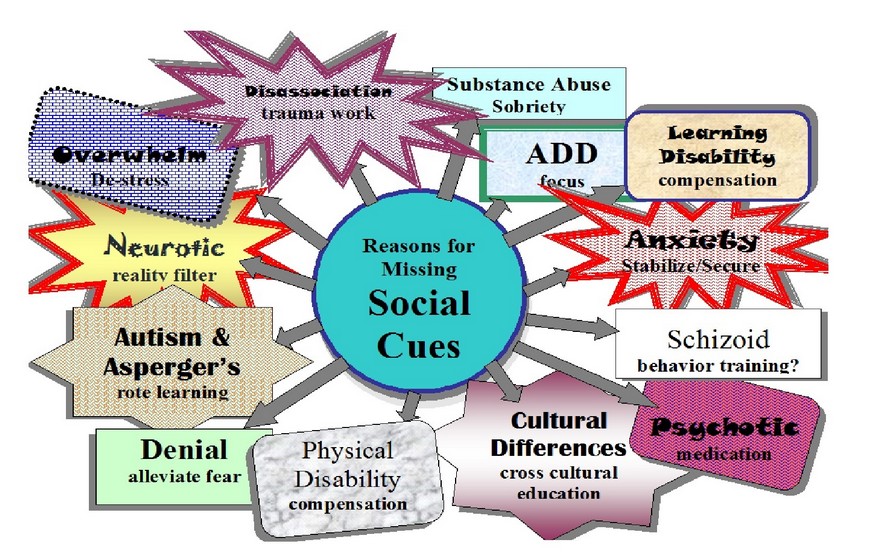

Jerry’s issue, AS, is one of at least thirteen reasons for missing social cues.

1. Aspergers Syndrome2. Physical Disability3. Cross-cultural Issues4. Overstimulation5. Denial6. Anxiety7. Neurosis8. Disassociation9. Learning Disabilities10. Attention Deficit Disorder (and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder)11. Intoxication/Substance Abuse12. Schizoid Personality Disorder13. Psychosis

Recognizing each issue and potential interaction directs responses or interventions to help individuals better recognize social cues.

Physical Disability #2– Compensation: “What?”

I crept forward to read the words. Later with glasses… wow! Individuals often develop intuitive compensations, whether or not they recognize a challenge. Intuitive compensations for a physical disability may include turning one’s ears towards sounds for example. Intuitive strategies may work relatively well or be stressful and risk misinterpretation. A Florida Today article (Best, 2007) described a young girl perceived negativity by teachers, peers, and herself. Finally, an eye examination discovered she had strabismus (cross-eyed). Vision therapy taught her to use different parts of her brain for focus and mental concentration. Her headaches and nausea went away. She got “smarter!” Unidentified physical disabilities or difficulties, specifically vision or hearing, can cause missing or misinterpreting cues. However, adults should be aware that receiving extra help in school is predictive of a child being bullied (Carter and Spencer, 2006, p.14).

Cross-cultural Issues #3- Cross Cultural Education: “So, that’s what you mean!”

Don said, “I wanted that last piece of pie. I thought Ronald was going to offer it to me again.” His girlfriend laughed, “You had your chance!” Don anticipated an exchange of polite refusal, polite insistence by the host, and more polite refusal and insistence. Whereupon, the guest graciously accepts! Propriety around courtesy cues occurs in many cultures. Japanese-American Don mistakenly assumed such a ritual culminating in his accepting the last piece. However, my question was literal. He said no, so I literally ate it! Cross-cultural education regarding social cues, courtesies, and rituals clarifies communication. The next time I offered Don the last piece, he immediately responded, “Yes!” Successful cross-cultural education! Purposeful cross-cultural education teaches how behavior or expectations serve the contextual demands of a community. Shared experience tend to lead to shared norms. Shared challenges may result in distinctive cultures, such as deaf culture- a term “developed in the 1970s to give utterance to the belief that Deaf communities contained their own ways of life mediated through their sign languages,” (Ladd, 2003, p.xvii). Therapists should look for other behaviors mediated by other shared demands.

Overstimulation #4- De-Stress: “I don’ wanna have fun!”

Failure to recognize accumulation or releasing stress creates overwhelmed or over-stimulated children. Over-stimulation interferes with ability to recognize non-verbal social cues. Therapy directs reducing stimulation through cutting back on activities, facilitating stress release, and so on. Additional therapeutic targets include family strife and chronic illness. Relatively minor stimulation such as fluorescent lights, tastes, smells, sounds, and dust floating in sunlight can become overwhelming to some children. For example, Attwood (2006) says that people with AS often describe feeling a sensation of sensory overload not readily apparent to others (page 272). Overwhelmed individuals lose focus, becoming more likely to be surprised by circumstances and situations that others notice. Therapists should address over-stimulation or over-whelm that causes acting out.

Denial – Alleviate Fear (#5 of 11), “No no NO!”

Eyes closed…“No no NO!” Children sometimes block out the intolerable. Individuals may find ugly or challenging experiences, emotionally or psychologically devastating… too much… too intense. Denial is a primary defense mechanisms. “When people are confronted with circumstances they find to be a threat, they often deny association or involvement with any aspect of the situation. Young children are often caught in the act of lying (denial) when they are accused of eating cookies right before dinner or making a mess in the bathroom. Examples in adulthood include denying a drinking or gambling problem. Any stimulus perceived to be a threat to the integrity of one’s identity can push the button to deny involvement or knowledge. At a conscious level, the person truly believes he or she is innocent and sees nothing wrong with the behavior” (Seaward, 2006, p.84-85).

Anxiety #6- Stabilize/Secure: “What? Where? Watch out? Where? Now?!”

Anxiety develops without something specific to fear and thus without specific remedy for the amorphous fear. Normal fears are managed through frequent positive experiences. Reassurance, support, and positive experiences and outcomes do not relieve habitually anxious people. Anticipating foreseeable issues, normal anxiety prompts scanning for social cues to mood and intent. Hypersensitivity and hypervigilance cause unnecessary scanning in benign situations and interpreting neutral social cues as threatening, leading to becoming over-cautious and overly negative. This re-ignites anxiety that exacerbates the anxiety-failure-anxiety-failure cycle. Resultant behavior destabilize the environment, heightening everyone's anxiety. Intervention targets breaking cycles of anxiety and failure by establishing predictable, stable, concrete, secure, and consistent interactions, relationships and environments.

Neurosis #7- Reality Filter/Check: “That was then, and this is then.”

“Here puppy.” A stranger reaches to pet the dog. The dog reflexively snaps. All cues indicated no danger. But the dog’s master had smacked its head… many times. The dog misinterpreted cues as “another smack coming!" Instincts and intuition from prior experiences alter interpretation and distort cues to fit expectations. Neurosis assume previous bad outcomes will repeat. Children need abundant positive reparative experiences to countermand such prior experiences. Frequent reality checks regarding cues counter neurotic filters. Identified patterns can be overtly challenged to discover partial influence, power, and control. Doom is predicted with declarative terminology such as:

“It must be…”“I will be…”“They must be going to…”“always…”“never…““all the time…”

Substitute terminology acknowledges potential problems but allow for other outcomes:

“It might be…”“I might be…”“They might be going to…”“could be or not!”“Sometimes…”“too often…”

Hope is allowed! It implies the possibility of increasing positive while decreasing negative frequency. Adults can challenge individual's neurotic self-definition as victims.

Disassociation #8- Trauma Work: “Click… This station is no longer broadcasting…or receiving.”

Disassociation occurs when experiences cannot be endured. Unconsciously, memory and feelings disconnect or are blocked. Devastating incidents or experiences such as chronic abuse, push one beyond conscious tolerance. Cues similar to original trauma may become triggers. Traumatized individuals may freeze or cause dysfunctional responses to triggers that others handle readily. The therapist can anticipate conflict situations, picking teams, tests, and so forth may be potential triggers based on individual's history, and mitigate triggers, for example by announcing, “I’m going to say something that sounds scary, but you'll be ok.” Adding touch- a hug to maintain emotional connection may reduce disassociation.

Learning Disabilities #9- Compensation: “Trying hard, and harder…”

What is said:

“First, pick a partner. Second, get the blocks from the tub. Third, go to page 3. Then, copy the structure there. After that, make up your own structure. Then draw a picture of it.”

What is heard:

“First, pick a partner. Second, tick tick (from the clock). Tick, go to… (rustling pages). Then, tick tick… it.”

Anxiety, neuroses, disassociation, and other issues that complicate reading social cues can arise with LD. Adult auditory teaching styles frustrate children with auditory processing issues, who may be strong visual learners. Auditory or visual instruction may not reach motor-kinesthetic strengths characteristic of LD and/or ADHD. Teacher-directed instruction versus child-centered orientations differentially serves managing impulsive energy. Adult structure might stabilize or stifle different children.

Missing instructions lead to mistakes and acting out to hide ignorance. Even when trying hard, many non-verbal facial, tonal, or body language cues get missed. Instructions may be heard but inefficiently processed into short-term memory creating “forgetting.” Inefficient cognitive retrieval of information, taking more time and concentration makes one oblivious to continuing cues from others. Classmates frustrated by a child’s poor responses label him or her "rude," "mean," and/or "weird. Whitney (2002) says, “Children with NLD (non-verbal learning disabilities) are frequently the target of bullies. Because they take things literally, because they are so trusting, and because they rarely tattle, they are the perfect victims. Often they can't tell the difference between bullying and friendly banter or dangerous intentions... A child with NLD won't be able to read the subtle cues that tell the bully the teacher isn't paying attention, so he is likely to assume the teacher sees the bully's behavior and condones it. Frequently the teacher hasn't seen the bully's behavior and the teacher only sees when the child with NLD reacts to the bully's taunts. A child with NLD will react whether the adult is around or not.”

Children may intuitively try harder, but with ineffective and/or inefficient tactics. Adults need to teach specific compensations for LD: auditory challenges with visual compensations; visual difficulties through auditory strengths; and so forth.

ADHD (and ADD) #10- Focus: “Huh? What?"

“…and Marc gets involved with his guitar,” complains Debra. Marc watches her. Gradually, his gaze wanders to a branch swaying in the window. “It’s just hard,” Debra says tearfully, head bowed, and hands clasped. Marc watches the branch. “And, he doesn’t care!” Debra snaps. “Huh? What?” Busted! But he does care. His attention wanes despite good intentions as it did in school. ADHD and ADD share the common issue of high distractibility. With wandering attention, someone like Marc misses subtleties of cues: tears, bowed head, clasping hands, and especially, the quavering voice. When Debra accepted that despite loving her, Marc’s ADHD made paying attention difficult, she accepted helping Marc focus. Marc took responsibility that attention was critical to their relationship. He improved recognition of her non-verbal cues. Classmates hurt by inattention they interpret as dismissive may feel entitled to vengeful retribution. Unaware of their transgressions, distracted children experience such treatment as unjustified. This may prompt retaliatory behaviors, which prompts further retaliation- negative cycles that may be broken with education about cues, boundaries, and consequences.

Intoxication/Substance Abuse #11: Sobriety: “Common adverse effects…”

Intoxication/substance abuse might seem most relevant to teenagers or adults. However, children might be on sedative or stimulant medication affecting alertness and focus. Cough medicine may include chemicals such as Dextromethorphan with possible side effects of dizziness, lightheadedness, drowsiness, nervousness, and restlessness (MedlinePlus, 2008). Albuterol (brand name-Ventolin HFA), an asthma medication may have a stimulant effect. Giedd (2003) surveyed research and found the diagnoses of ADHD and substance abuse occur together more frequently than expected by chance alone. The National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University (2000) examined the link between LD and substance abuse finding, “…adolescents with low self-esteem may use drugs for self-medication purposes--to counter negative feelings associated with social rejection and school failure… Some specialists believe that people with ADHD medicate themselves with drugs such as alcohol, marijuana, heroin, pain medication, caffeine, nicotine and cocaine to counter feelings of restlessness” (p.9). Ritalin, a common ADHD medication easy to obtain, has been used as a recreational or self-medicating drug (addictionsearch.com, 2013). Self-mutilation or self-injury might be considered self-medication since they trigger physiological responses that include whole canopies of chemical responses that numb not just physical pain but also painful emotions. Timofeyev, et al (2002) suggests that in addition to dopamine, “endogenous opioids have also been linked to self-mutilation. The biological reinforcement theory suggests that the pain from self-mutilation may cause the production of endorphins (endogenous opioids) that reduce dysphoria. A cycle is formed in which the habitual self-mutilator will hurt themselves in order to feel better.” Workaholism, gambling, and other behavioral compulsivity can also activate biological processes for self-medication. Behavioral compulsions or acting out may be the first and only observable indications of individuals’ depression or anxiety and should activate appropriate referrals or support.

Schizoid Personality Disorder #12- Behavior Training

People with schizoid personality disorder (APA, 1994, p.638) recognize social cues correctly, but are indifferent to most common social processes. Schizoid individuals don’t seem to enjoy, miss, or desire relationships or intimacy, and are generally unavailable to motivation other than perhaps behavior training directed at dealing with specific problems in daily functioning. Long-term change is difficult given individuals’ apparent disinterest. This category was included to be comprehensive rather than a likelihood of applicability to children.

Psychosis #13- Medication

A nervous breakdown used to be called vapors, melancholia, neurasthenia, neuralgic disease, or nervous prostration. Clinical descriptions found in DSM-IV or DSM-V (APA, 1994, 2013) include psychotic break, psychosis, schizophrenic episode, catatonia, manic break, post-traumatic stress disorder, panic attack and major depressive episode. When psychotic, individuals respond to internal cues causing gross misinterpretation of non-verbal cues or anything else. Extreme stress, depression, anxiety, fear, mania, or trauma can cause temporary psychosis. Individuals often re-stabilize back to normal functioning. Some breakdowns precipitate deeper and permanent mental and psychological disabilities. Psychopharmacological intervention is the dominant treatment for long-term or ongoing psychosis.

CONCLUSION

Children, teens, and adults may have depression, anxiety, or personal and relationship issues with multiple interactive roots. Therapy may orient towards dealing with symptoms and/or with etiological factors. An important diagnostic consideration is the potential influence on inter-relational functioning and subsequent self-esteem of ones accuracy interpreting non-verbal social cues. And, of how inaccurate interpretation can lead to problematic acting out behavior that become the target of discipline, and hence of therapy. Effective therapy and interventions would derive from not only addressing behavior adjustments but also to the underlying roots and factors precipitating the chain of processes for the child or teen (or adult). Children and adults frequently behave in inappropriate or mysterious ways possibly due missing social cues from one or more of the thirteen reasons. Identification of how and why social cues are missed may itself be highly normalizing to distressed children. Often, several of these reasons co-exist to compromise a person’s functioning. These conceptualizations may guide purposeful intervention and more effective therapy for a Jerry and his family.

References:

addictionsearch.com. Ritalin Abuse, Addiction and Treatment. www.addictionsearch.com. Retrieved November 24, 2013, from http://www.addictionsearch.com/treatment_articles/article/ritalin-abuse-addiction-and-treatment_43.html.

American Psychiatric Association (APA). (1994). The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV). Washington, D.C., 1994.

American Psychiatric Association (APA). (2013). The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-V). Washington, D.C., 2013.

Attwood, T. The Complete Guide to Asperger’s Syndrome. London and Philadelphia: Jessica Kingsley Publishers, 2006.

Bauer, S. Aspergers Syndrome. O.A.S.I.S. (Online Aspergers Syndrome Information and Support), 1996. Retrieved February 15, 2008, from http://www.udel.edu/bkirby/asperger/as_thru_years.html.

Best, K. Prioritize the eyes, get checked. Florida Today, August 14, 2007. Retrieved on, August 15, 2007, from www.floridatoday.com

Carter, B. B. and Spencer, V. G. The Fear Factor: Bullying and Students with Disabilities. International Journal of Special Education, Vol. 21, 1, 2006.

Giedd, J. ADHD and Substance Abuse. Medscape Psychiatry & Mental Health, 8(1), 2003. Retrieved on March 3, 2008, from http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/456199_print.

Gordon, N. J. and Fleisher, W. L. Effective Interviewing and Interrogation. Academic Press, 2002.

Ladd, P. Understanding Deaf Culture: In Search of Deafhood. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters, 2003.

Long Beach City College Foundation. Communicate! A Workbook for Interpersonal Communication. Dubuque, IA: Kendal/Hunt Publishing, 2004.

Mandic, T. Body Language in Debating. The Karl Popper Debate Program of the Open Society Institute and the Network of Soros Foundations, 2008. Retrieved on March 3, 2008, from http://www.osi.hu/debate/body.htm.

MedlinePlus website. Drugs and Supplements: Dextromethorphan. www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus, 2008. Retrieved on March 3, 2008, from

http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/druginfo/medmaster/a682492.html#side-effects.

National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University. Substance Abuse and Learning Disabilities: Peas in a Pod or Apples and Oranges? National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University, 2000. Retrieved on August 22, 2008, from http://www.eric.ed.gov/ERICDocs/data/ericdocs2sql/content_storage_01/0000019b/80/17/01/ad.pdf.

Schwartz-Watts, D. M. Asperger’s Disorder and Murder. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, 33:390-3, 2005.

Seaward, B. L. Managing Stress: Principles and Strategies for Health and Well-Being. Boston: Jones & Bartlett Publishers, 2006.

Timofeyev, A. V., Sharff, K., Burns, N., and Outterson, R. Self-Mutilation: Motivation. http://wso.williams.edu, 2002. Retrieved on March 28, 2008, from http://wso.williams.edu/~atimofey/self_mutilation/Motivation/index.html.

Whitney, R. V. Bridging the Gap. New York: Berkley Publishing Group, 2002.

Your Little Professor, Resources and Academic Programs for Children with Asperger’s Syndrome. Bullying (and Asperger Syndrome). www.yourlittleprofessor.com, 2008. Retrieved on March 16, 2008, from http://www.yourlittleprofessor.com/bullying.html.