14. Cycle of Tension-Cycle of Violence - RonaldMah

Ronald Mah, M.A., Ph.D.

Licensed Marriage & Family Therapist,

Consultant/Trainer/Author

Main menu:

14. Cycle of Tension-Cycle of Violence

Therapist Resources > Therapy Books > Conflict Control-Cple

Conflict, Control, and Out of Control in Couples and Couple Therapy

Chapter 14: CYCLE OF TENSION – CYCLE OF VIOLENCE

by Ronald Mah

Regardless of what ignites what or comes first, the therapy needs to be able to recognize the warning signs of abusive control. The therapist should examine "the level of control, usually of the male partner over the female partner. Samenow (1995) suggests abusive men experience a need to control some aspect of their lives and this need is often fueled by an extreme emotional dependency on the female partner. To cover their dependency or seek to keep the dependency operative, they intimidate or dominate the person they ostensibly love and/or depend on the most. This pattern also often exists in at-risk couples. Abusive control includes behaviors such as a demanding or coercing interpersonal involvement and/or sex, extreme jealousy, and preoccupation with unfaithfulness, interrogating, checking or stalking the partner, restricting contact with others, and dictating dress or personal preferences. Coercive ultimatums such as 'If you do or don't do, then I'll.' Threats of violence toward inanimate objects or animals are also signs of abusive control. These behaviors are potential precursors of spousal battering" (Perez and Rasmussen, 1997, page 233. The therapist may see a version of coercion, jealousy, and other controlling behaviors in the session. The therapist can create a forum for the couple to discuss the dynamics underlying causes in the controlling partner and the effect on the other partner. If Dirk is unwilling to allow this kind of forum to open, then this in of itself potentially is an indication of trying to control Madeline through restricting communication. Frustrating Madeline from having her voice becomes another warning sign.

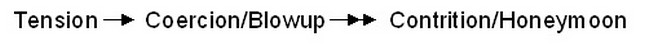

The therapist should assess for a cycle of rising tension as related to a potential cycle of violence. Looking at how tension increases is important for prevention if Dirk and Madeline have not crossed over to physical violence, but are involved in frequent arguments. There may be no physical abuse. However, the therapist should consider emotional or psychological violence as a subset or a precursor to physical violence. Therefore, using a cycle of violence model may prove beneficial regardless. "One diagnostic indicator is the presence of a 'cycle of violence' process (Walker, 1983). We assume that at-risk couples do not have defined 'cycles of violence,' however aggressive arguments follow similar patterns of those identified in violent couples. With at-risk couples, we call this the 'cycle of tension.' This cycle is diagrammed below:

In exploring this cycle, the focus understands the couples' unique expression of it and how it has become entrenched in their relationship (Pagelow, 1984). Typically, the cycle is reinforcing because of the associated release of tension and seductive contrition/honeymoon phase. External stressors, conflict avoidance, and/or poor conflict resolution also serves to fuel the cycle. In this way, heated arguments become mechanisms for tension reduction and intimacy modulation, rather than a more differentiated, less emotionally reactive problem resolution and negotiation process" (Perez and Rasmussen, 1997, page 233), "…during the remorse phase of the violence cycle, the husband may engage in greater levels of intimacy and caring to offset the violence (Walker, 1979). These positive events, when they occur, may function to maintain love for the spouse and to facilitate hope for change in the husband's behavior, thus retaining the woman's commitment to a violent marriage" (Langhinrichsen-Rohling, 1998, page 198). The partner seems to have selective memory for the positive experiences while forgetting or minimizing the abusive experiences. Madeline may have a profound need- a desperate need for love (perhaps, insecure attachment needs) that mandates her self-deception about Dirk being loving and believing his promises. Although, she is crushed by subsequent abuse, her desperate fear of abandonment and rejection compel her to "forget" or minimize previous promises betrayed. Her need for the illusionary and transitory security of Dirk's love is greater than her need for real safety and security. She participates in the cycle repeatedly.

Any problem that is determined to involve a cycle of behaviors or sequential and progressive elements lends itself to strategic therapy interventions. As the therapist evokes the cycle, sequence, or hierarchy of events, emotions, thoughts, actions, and reactions, the partners are directed to interventions to interrupt or alter the process. Any element in the cycle, sequence, or hierarchy that is disrupted or blocked creates a potential change in the overall process- possibly for the better. In a cycle of tension, interventions can target eliminating or reducing stress, altering or switching to behaviors that alleviate rather than increase tension, and promoting connective nurturing behaviors while blocking destructive toxic choices. The therapist targets anything and anywhere in the cycle between Dirk and Madeline, including outside stimuli acting on either of them that might be altered. The most difficult element in their cycle may be Madeline's insecure attachment that drives her acceptance and re-entry into dysfunction. Although this is a primary essential element in the cycle that must be changed, it may be the most difficult to address because of its deep developmental history.

An important principle of problematic behavior as related to some negative cycle is that the origins of the cycle may be deeply embedded in the history and/or prehistory of the partners. In that sense, while every part of the cycle: actions, feelings, thoughts, etc. have a precursor and a subsequent reaction, there is no relevant "first" action that "started it" within any recent time period. Dirk and Madeline will inevitably argue about who did what first and how his or her behavior was in response to that initial transgression. They will implicitly or explicitly ask the therapist judge one as the instigator. Instead of assigning guilt for an original sin, the therapist should assert that any and every action that is not a clearly and overtly positive attempt to nurture and respect one another is "wrong." Actions or behavioral choices are benign, make things better, or make things worse. The therapist should hold each partner accountable for having made things worse with bad choices. A key to or target for breaking negative cycles therefore includes each individual's inferences, interpretations, or assumptions about the other partner. Individuals often have negative or hostile judgments about the partner's thoughts and feelings. They anticipate negativity emanating from the partner.

"At first glance, the findings regarding participants' inferences about their spouses' thoughts/feelings appear to be consistent with the idea of cognitive distortions or biases among violent spouses—relative to nonviolent spouses, violent spouses were more likely to report that their spouses were experiencing aggressive cognitions. However, other findings lead us to conclude that the violent participants' inferences about their partner's thoughts/feelings are not inaccurate. First, when considering husbands' cognitions, levels of aggressive cognitions in husbands' self-reports and in wives' inferences regarding husbands' thoughts/feelings did not differ significantly, suggesting that wives were accurately perceiving their husbands' level of aggressive cognition. Second, objective observers' inferences also revealed violent versus nonviolent group differences in levels of aggressive cognitions, suggesting that violent spouses are somehow conveying their higher levels of aggressive thoughts to objective observers (and spouses). Third, using difference scores to compare the level of aggressive cognitions in spouses' self-reported thoughts/feelings versus in their partners' inferences about those thoughts/feelings, group differences did not reach statistical significance. This suggests that when spouses self-reported aggressive cognitions, their partners (even violent partners) accurately perceived these aggressive cognition… It remains possible that violent spouses would be less accurate in understanding their partners' thoughts and feelings in other situations, such as when discussing a new problem or when the partner's behavior is ambiguous. In such situations, violent spouses may apply any existing cognitive biases to their interpretation of partner behavior" (Clements and Holtzworth-Monroe, 2008, page 365).

Dirk would not be incorrect necessarily that Madeline is angry, blaming, and resentful towards him. He may also be correct that Madeline's thoughts are aggressive despite her claims of innocence. Greater ability on his part to tolerate Madeline asserting herself and doing so aggressively can moderate his reactions and responses. In addition, if Madeline crosses the boundary and her aggression becomes psychologically and emotionally abusive, then productive interactions depend in part on his ability to resist reciprocally acting out his hurt or anger. As he can hold himself within that boundary, he also needs to assert the boundary that Madeline cannot be abusive. "You can be angry at me, but I will not accept you putting me down or insulting me… and I will resist disrespecting you while I'm mad at you." Madeline's difficulties may include her lack of awareness or ownership of her anger and aggressive thoughts about Dirk. And, how she may psychologically or emotionally abuse him. That would include passive-aggressive actions, including manipulating or using the children as proxies in her battle. Therapy may need to help Madeline take ownership of her anger and aggression and teach her positive assertive behaviors versus abusive tactics.

A core barrier to change however is if Madeline is already a victim of domestic violence and/or already psychologically abused to the point of being deeply intimidated. Prior tentative and ineffective attempts to assert herself may have drawn psychologically and emotionally abusive reaction if not physical abuse. The therapist prompting her to be more assertive may place her squarely in Dirk's line of fire, making her likely to be abused again. Depending on the severity, emotional and psychological abuse may be managed sufficiently for Madeline to practice acting more assertively. However, a history of intimate partner violent abuse increases the risk of… actually almost guaranteeing triggering further and more dangerous violence. Assertiveness training including direct communication becomes appropriate interventions only when both partners have agreed to a safe environment or relationship to confront one another. Although, the therapist may be clear that Madeline needs to confront and resist Dirk's aggression and abuse to have the possibility of becoming psychologically healthy and a functional relationship, Dirk must have sufficient ego strength and emotional restraint to tolerate the process. Therapy must first assess Dirk's abusive style and be able to significantly curtail if not absolutely block a physically violent reaction to any behavior or change in behavior by Madeline. Therapy and intervention must change directions if safety cannot be secured.

DISINHIBITION

Since alcohol use has been found to be a major influence on domestic violence, reduced or elimination of drinking may help make partners' dynamics safer. "Male drinking during an incident is associated with increased severity and the risk of injury. Alcohol-related problems among women predicted female perpetrated violence among Whites, Blacks, and Hispanics; while male alcohol-related problems predicted violence only among Blacks. Heavier drinking among men is positively associated with female initiated violence, while among women, heavier drinking is associated with chronic female violence" (Ramisetty-Mikler et al., 2007, page 32). Alcohol functions as a disinhibiter as it depresses brain functions that inhibit impulsive reactions. When therapist determines that alcohol consumption has contributed to abuse, the individual should be directed to taking responsibility for knowingly increasing his or her volatility by continuing to drink. For those individuals with tendencies to rage and violence, developing the ability to inhibit such tendencies becomes fundamental to safety and change. The therapist should anticipate using alcohol as an excuse for abuse. "The reasons why alcohol should lead to violence have been the subject of extensive study in relation to general aggression (see reviews by Graham, Wells, & West, 1997; McMurran, 2002). It is true that the relationship may be spurious, in that alcohol may be used as an excuse, a justification, or a facilitator in relation to aggression (Zhang, Welte, & Wieczorek, 2002). First, people may blame their aggression on their drinking post hoc. Second, some people may drink prior to aggression or violence so others will excuse their behaviour on the grounds of drunkenness. Third, some people may drink to embolden them to commit acts of aggression or violence" (McMurran and Gilchrist, 2006, page 112).

Alcohol use can be examined from the perspective of cognitive processes necessary for social problem solving. Using alcohol as an excuse or "'deviance disavowal' may relate more to instrumental types of domestic violence. Most relevant to domestic violence that is motivated by anger during conflict or affective defence is the way alcohol affects higher order cognitive activities in such a way as to make aggression more likely. Alcohol interferes with those processes which are needed to control behaviour and act in a planful way to achieve the best outcomes in any situation, namely attention, abstracting relevant information, reasoning, problem-solving, planning, and self regulation (Pihl & Hoaken, 2002). These processes are collectively called executive cognitive functioning (ECF), and one specific set of skills to which these processes are integral is social problem solving (Zelazo, Carter, Reznick, & Frye, 1997)… The effect of alcohol on domestic violence is moderated by hostility, marital discord, and negative affect (Leonard & Blane, 1992). Where there is hostility, conflict, and bad feeling in any relationship interaction, one response is to take steps to ameliorate the situation through interpersonal problem solving. Obviously, alcohol intoxication will impair social problem solving and as an acute dynamic risk factor drinking requires attention. More fundamentally, both drinking and violence need to be addressed by targeting the stable dynamic risk factor of social problem solving"(McMurran and Gilchrist, 2006, page 112).

Social information processing is compromised by alcohol increasing feelings of frustration that lead to helplessness and/or rage. Alcohol use for self-medication for anxiety and depression associated with self-esteem and relationship distress can become major contributor to intensifying self-esteem and relationship problems. Alcohol use may contribute to or trigger partner abuse and relationship problems, which in turn trigger further self-medication with alcohol. Domestic violence worsens the relationship further deepening loss and rejection feelings, again leading to self-medication with alcohol. And around and around it goes. Identifying the original root of problems may be less important than accepting the circularity of causation and attempting to interrupt or block it. If abuse can be stopped or blocked or reduced… if alcohol use is blocked… if relationship quality is improved… if emotional distress is soothed… if anger arousal lowers… if better communication is practiced… if negative thoughts or inferences are replaced by positive cognitions… and so forth, the therapist should direct therapy in that direction. Whatever is available to intervention and change becomes a target of therapy, and a change in any part of the cycle creates a possibility of the cycle changing for the better.

Alcohol is a factor in violence committed by some individuals in some circumstance. It is less of a contributor to violence for some, while more dangerous for others. "…there is evidence to suggest that alcohol is unlikely to predict the occurrence of a violent episode among individuals who have very low hostile motivations. Instead, alcohol appears to act synergistically with hostile motivations to predict the occurrence of violence (Bailey & Taylor 1991; Jacob et al. 2001; Giancola 2002; Giancola et al. 2003). However, there is also evidence that among individuals with very high levels of hostile motivations, alcohol does not appear to contribute to the occurrence of violence (Blane, Miller & Leonard 1988; Rice & Harris 1995). Very recently, we have reported evidence that suggests that drinking on a specific day is associated with the occurrence of severe violence among antisocial men, but that it is not associated with the occurrence of non-severe violence among these antisocial men (Fals-Stewart, Leonard & Birchler, in press). Taken together, these findings suggest that the occurrence of a violent episode among the most violent, antisocial men is not related to alcohol consumption, but that alcohol consumption may increase the severity of the violent episode" (Leonard, 2005, page 424). While alcohol consumption increases how dangerous someone may become, it is apparent that some individuals are fundamentally more dangerous with or with alcohol use. They are more dangerous whatever other triggers, influences, circumstances, or their partners' behaviors. The therapist should query Dirk on how he regards alcohol, on his alcohol use, and how it affects him. Madeline is an important witness and can verify or expand on Dirk's rendition of his relationship with alcohol and its possible contribution to aggression and abuse. Is alcohol consumption, for example a way Dirk deals with stress and/or does it contribute to his stress in one way or another?

STRESSORS

Stress has significant influence on domestic violence. Problems and conflict in the couple is affected by a multitude of stressors: work issues, financial problems, child raising challenges, health and medical problems, and so forth. Multiple stressors often combine and interact with one another to create greater pressure than the sum of stresses. For example, Kim and Sung (2000) identify how Korean immigrants encounter multiple stressors in the new cultural context, such as language barriers, children's education, employment problems, discrimination, alienation, etc. (page 334). Petersen and Valdez (2004) describe female Hispanic adolescents who encounter minority stress (cultural differences, discrimination, limited resources, and so forth) along with teen issues and requirements of familismo to value family cohesion over individual needs (page 72). Gay and lesbian individuals may deal with stresses shared in common with straight individuals while also dealing with hiding their homosexuality or being out in homophobic and heterosexism communities. Stress can be defined as a function of the interaction between the subjective experienced requirements in a situation relative to the person (or couple) being able to meet the requirements adequately. Stress may be tolerable and formative if demands can be dealt with well. However, negative or excessive stress occurs when requirements exceed the capacity, skills, or resources of the individual or couple to respond adequately. Failure to handle stress is itself very stressful. Anticipation that one will not be able to handle stress or demands is also stressful. Memories of prior failure to manage prior requirements further add to stress. Emotional or psychological aggression, abuse, and domestic violence are dysfunctional reactions rather than productive reactions among other stress response styles or behaviors.

Kim and Sung (2000, page 339) propose a Life Stress Table that they surveyed Korean-American immigrants on which stressors were in their lives. They can be relevant for other individuals regardless of ethnicity. The following stressors were identified as relevant to at least twenty percent of those surveyed.

Trouble with bossTrouble with other people at workGot laid off or fired from workDeath of someone closeA lot worse off financiallyBig increase in arguments with spouse/partnerBig increase in hours worked or job responsibilitiesDiscriminated against in housing, or in any other way

Difficulties in speaking English

Other potential stressors included the following:

Got arrested or convicted or something seriousForeclosure of a mortgage or loanBeing pregnant or having a child bornSerious sickness or injurySerious problem with health or behavior of family memberSexual difficultiesIn-law troublesSeparate or divorcedMoved to different neighborhood or townChild kicked out of school or suspendedChild got caught doing something illegalDifferent values with childrenCrime victim

The therapist should assess each partner and the couple or family for stressors. For each individual and couple or family, there is almost inevitably a multitude of stressors. They may be relatively minor stressors readily managed or very difficult stressors that take up extraordinary energy and focus that are unfortunately not well handled or reduced. The therapist should check with each partner for what he or she experiences as relevant challenging stressors for him or herself and for the partner. There may be major discrepancies between what each partner considers to be stressful. The therapist should be especially attentive to an individual minimizing or dismissing a stressor that his or her partner experiences as compelling. Dirk may dismiss Madeline's complaint about her difficulties dealing with household and childcare pressures. Madeline may minimize Dirk's description of the pressure he feels at work as justification to avoid coming home. This indicates the partners being out of sync. When someone's expressed stressor is minimized or dismissed by the partner, he or she feels disrespected and discounted. This significantly adds to and intensifies the stress between the partners. Getting each partner to accept and validate the other's experience of stress becomes a key component of reducing overall stress. Kim and Sung's findings about Korean-American immigrants appear relevant to other couples. "High stress couples had the highest level of any violence; 38% of the high stress couples experienced a physical assault during the year. On the other hand, only 2% of the low stress couples experienced such an assault. Nearly 39% of the husbands who had high stress committed one or more violent acts against their wives compared to less than one out of 66 husbands who had a low level of stress. None of the husbands in the low stress families committed a severe assault against his wife. In contrast to this, rate of severe violence or wife beating by the husbands in the high stress families was 16.3%. Each additional stressor increased the chance of wife abuse" (Kim and Sung, 2000, page 339).

Pregnancy is a key stressor in most relationships. Pregnancy may be unplanned and unprepared for. It can complicate already fragile relationships. Sometimes, getting pregnant is seen as a way to solidify otherwise unstable relationships. Often times, whether the pregnancy is intentional or accidental, it keeps two partners together that would have otherwise separated. Even when it is mutually planned, both partners experience multiple stresses and the relationship is stressed as well. There are immediate stresses including pre-natal care, diet, and maintaining or altering work schedules. There are anticipatory stresses about living arrangements, financial demands, balancing family obligations, parenting, and so forth. In addition, emotional and psychological anxieties from possibly duplicating problematic parenting experienced in childhood- that is, doing better than ones parents, doing as well, doing the same, or doing worse. Increased stress from pregnancy can affect many areas of functioning including aggression and abuse.

"Most research that has assessed women's abusive experiences both before and during pregnancy has found that somewhat greater proportions of women have been abused before pregnancy than during pregnancy and that the majority of women abused during pregnancy also were abused before pregnancy" (Martin et al., 2004, page 201). Pregnancy then did not alter frequency or severity of abuse for some couples (43%), implying that the additional vulnerability of the mother-to-be and the life within her were not sufficient to curtail abuse. While abuse decreased in frequency or severity for more women (36%), it increased for a significant number (21%) (page 202). Among women (termed index women) who reported to researchers that they were physically abused, "all three types of violence victimization were more frequently experienced by index women compared to their male partners, with statistically significant differences found for psychological aggression before pregnancy, physical assault before pregnancy, and sexual coercion before and during pregnancy. Further, the rates of violence-related injuries, both before and during pregnancy, were significantly higher among index women than among their male partners, with the women being injured an average of 0.79 times per month before pregnancy and 1.10 times per month during pregnancy (page 208). The higher frequency of injury from before to after pregnancy seems to imply that the physical abuse was more severe. The perpetrators may be hypothesized to be more aroused and less in control.

Psychological aggression increased for both men and women in both the index group and the control group with the beginning of pregnancy. "This finding is consistent with past research that has found that arguing with partners often increases when a couple becomes pregnant (Martin et al., 2001a). Thus, it appears that the stresses and life changes brought about by pregnancy may lead to increased verbal arguing by the couple; however, this may not necessarily translate into increased physical and/or sexual violence" (Martin et al., 2004, page 208). While pregnancy is an identified stressor that raises the risk for psychological aggression and domestic violence, it may be that the couple has embedded problems managing stress in general. The quality of pregnancy with its functional and symbolic demands may be uniquely stressful, but at the same time all other life stresses also trigger poor emotional regulation and conflict resolution skills. The tendency to psychological aggression and emotional abuse may be the characterological behavioral core in individuals vulnerable to activation by a multitude of stressors.

Therapeutic strategy would involve reducing or eliminating stressors; mitigating, replacing, or eliminating negative stress response styles and behaviors; and accentuating and developing positive stress response styles and behaviors. It remains important for the therapist to remember that cultural qualifications remain relevant with any strategy. "Intervention should primarily consider stressor stimuli and stress management. Intervention programs, which help male abusers identify sources of stress and to control stress and aggressive behavior through 'time-out' and 'self-talk' techniques, would seem beneficial (Koval et al, 1982). But Koreans have a strong tendency to confide their family problems only to close kin or intimate friends. Consequently, some of them would rather hide such marital problems. This culture-rooted behavior creates problems for the professional care provider. Any service would have to be provided to them in conjunction with the family-centered approach. In order to better serve the needs of victims of family violence, community agencies, churches and domestic violence programs in Korean American communities must begin to work together on various strategies including intervention, prevention, and public education" (Kim and Sung, 2000, page 343). For a couple such as Dirk and Madeline in addition to ethnic or community cultural qualifications, their respective family-of-origin cultural models may be as or more compelling for adapting strategies and interventions.

OTHER DEMOGRAPHIC CLUES

"Recent research has identified differences in the risk of homicide victimization based on the type of intimate relationship between two people who reside together" (Mouzos and Shackelford, 2004, page 207). Research in the United States and Canada find that unmarried men and women who live together are much more likely to be killed by their partners than couples who are married. "In Australia, married men were killed by their partners at a rate of 1.3 men per million married men per annum, whereas cohabiting men were killed at a much higher rate of 21.1 men per million cohabiting men per annum" (page 210). Women are more likely to be victims, although unmarried men are also more likely to be killed by their female partner. In their Australian study, Mouzos and Shackelford found that men are killed usually by another man- a friend or acquaintance. Only 10 percent of men were killed by their partner. On the other hand, when women kill the victim is most likely to be someone from within their family- usually the partner. Men are more likely to be killed by a non-partner than a partner, while women are much more likely to be killed by a partner than a non-partner. "Close to three-fifths of women killed in Australia are killed by a male intimate partner [Mouzos, 2001]. Similar patterns have been identified for the United States [see, e.g., Daly and Wilson, 1988]" (Mouzos and Shackelford, 2004, page 211).

Age differences show greater risk for female partner killing male partners. "Using national-level Canadian homicide data, Wilson et al. [1993] report that men in cohabiting relationships are about 15 times more likely to be killed by their female partners than are married men. Further research by Wilson and Daly [1994; and see Daly and Wilson, 1988] finds that, within marital relationships, men in their teens and early 20s are at greatest risk of being killed by a partner. Within cohabiting relationships, in contrast, middle-aged men, in their 40s and 50s, are at greatest risk of being killed by a partner. Finally, Daly and Wilson [1988] report that, in both marital relationships and cohabiting relationships, the age difference between the man and the woman predicts a man's risk of being killed by a partner. Men in both types of relationships are at greater risk of being killed when partnered to women who are either much older or much younger than they are" (Mouzos and Shackelford, 2004, page 207). It is not clear from statistics alone for the causes or motivations for killing the male partner. The greater likelihood of significantly older or younger men compared to their partners may be related to some inherent power differential created or reflected by age. Perhaps, significantly older male partners may be more rigid and dominating and homicide may be the result of female frustration and resistance. On the other hand, susceptibility to romantic manipulation in the relationship may cause older men to become targets of younger sociopathic women seeking financial gain. With older women killing young male partners may come from confrontations over older women's engrained power expectations and demands developed over time against culturally sanctioned but impulsive immature male aggression and dominance. The therapist should explore such speculations for possible relevance with the partners and the couple to assess potential risk of emotional or psychological abuse in addition to physical abuse. Stresses may be part and parcel of demographic circumstances. Stress may lead to demographic outcomes and demographic conditions may contribute to stress. Relevance and directionality of influence cannot be determined until the therapist investigates the partners and the couple in therapy.

The therapist will often hear relationship histories that describe wonderful compatibility and idyllic interactions. The key to longer relationship viability however is not how great ones partner may be when everything is going great. What predicts successful relationships is how ones partner steps up in crises when one or both partners are under duress. Or, if the partner shuts down, hides or funs away, uses drugs or alcohol to manage feelings... is emotionally, psychologically, or cognitively disconnected. Relationship health is destroyed if the partner becomes emotionally and psychologically aggressive and abusive or physically abusive under stress. While Dirk and Madeline may describe honeymoon or fabulous times, the therapist needs to uncover the negative times. The situations themselves or the actual demands or stresses are often less important than how each partner handles them. Focus on eliminating stress can be overemphasized, since stress is an inherent part of life and of the intimate relationship. The partners may present their scenarios and choices for approval. The problem solving or solutions are often must less important than how each partner responds. Is the partner to be relied on? What does he or she do when things are going badly? Is he or she trustworthy... consistent... helpful... supportive? Or not? When experienced in the negative, whatever the original stress or demands may have been, the problem is no longer a stress or demand but becomes their process and the relationship.