4. Not Getting It In the Couple- I - RonaldMah

Ronald Mah, M.A., Ph.D.

Licensed Marriage & Family Therapist,

Consultant/Trainer/Author

Main menu:

4. Not Getting It In the Couple- I

Therapist Resources > Therapy Books > Odd Off Different-Cpl

Off, Odd, Different… Special? Learning Disabilities, ADHD, Aspergers Syndrome, and Giftedness in Couples and Couple Therapy

Chapter 4: NOT GETTING IT IN THE COUPLE- Part I

REASONS INDIVIDUALS DON'T GET IT!

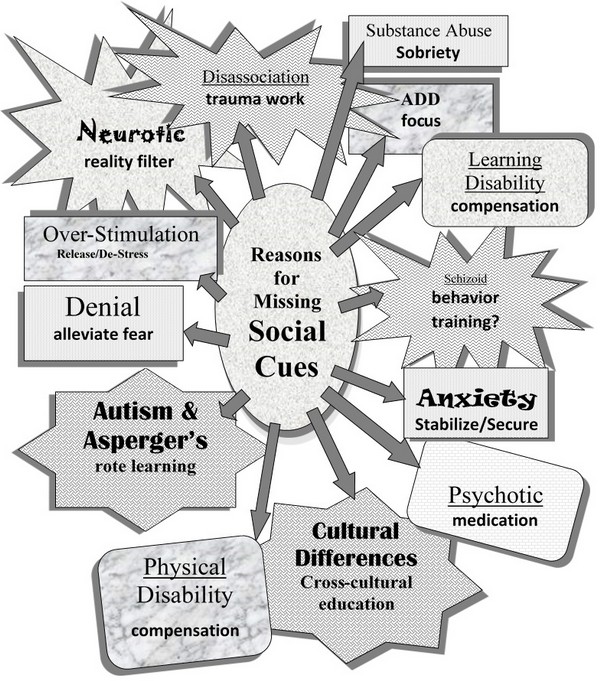

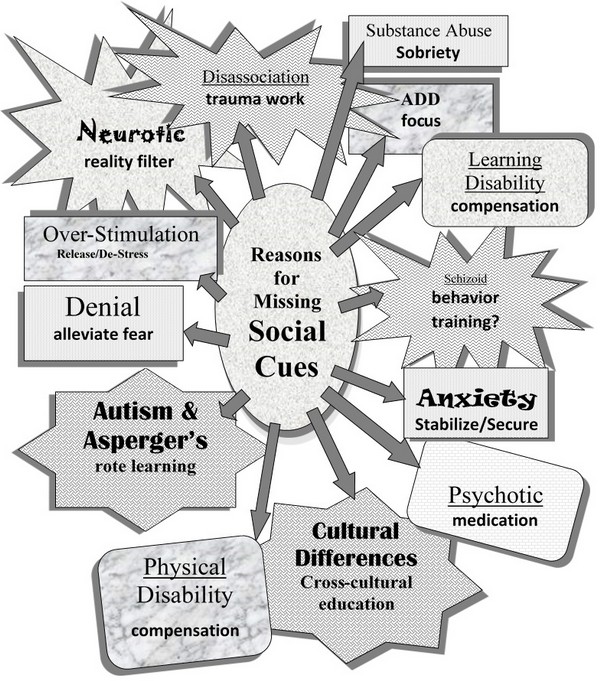

There are several reasons the therapist should consider regarding misinterpretation of non-verbal social cues. Placing these challenges among other issues affecting social cues recognition can lead to differentiated interventions for supporting a client. Brody's primary issue, Aspergers Syndrome is one of at least thirteen reasons for missing social cues. Missing social cues is a significant detriment to emotional, psychological, cognitive, and social development. Moreover, missing social cues can interact with other dynamics: attachment, family or cultural models, trauma, and other experiences to result in or exacerbate communication and relationship problems, academic and vocational issues, and mental disorders- including personality disorders. More than one reason for missing cues may also be relevant depending on a person's makeup and experiences. The following are (including Aspergers Syndrome) potential issues causing problems in reading social cues that can result in subsequent relationship distress.

1. Physical Disability2. Cross-cultural Issues3. Overstimulation4. Denial5. Anxiety6. Neurosis7. Disassociation8. Intoxication/Substance Abuse9. Schizoid Personality Disorder10. Psychosis11. Aspergers Syndrome12. Learning Disabilities13. Attention Deficit Disorder (and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder)

Work with the therapist about the relevance of any of these issues may be critical to therapeutic progress. However, an individual may have difficulty accepting a diagnosis of any kind that may imply some deficiency. As the therapist is aware of possible stages of acceptance, he or she can help the individual work through them. Goldberg et al. has a description of the Stages of Acceptance of the LD (learning disability) that can be applicable to an individual accepting any such diagnosis. Participants described a major struggle with a process they termed "acceptance of the learning disability." Many passed through similar stages working toward acceptance of the label of "learning disabled," including: (1) awareness of difference; (2) the labeling event; (3) acceptance/negotiation of the label; (4) compartmentalization; and (e) transformation. The reader is referred to E. L. Higgins, Raskind, Goldberg, and Herman (2002) for a complete discussion of this subject. (Goldberg et al., 2003, page 231).

The couple's process may need to divert to identifying the relevance and impact of challenges to the individual's functioning before addressing its effect on the couple. The first stage of awareness of difference comes from the therapist noting behaviors that may be indicative of a difference. He or she proceeds to inquire further about behaviors, experiences, and feelings that would be consistent with the potential diagnosis. For example, if the therapist suspects the possibility of a learning disability, he or she could ask about school experiences, frustration, trying hard, feeling dumb, missing or having difficulty getting information, and other common experiences of someone with a learning disability. If the therapist notes some characteristics of trauma, he or she would make inquiries about highly stressful or traumatic events in the person's history. If considering the possibility of Aspergers Syndrome, the therapist could examine Theory of Mind abilities for example. The partner can be especially informative in this inquiry. And so on for other potential diagnoses. The therapist may find using provocative lay language to be particularly effective for eliciting self-examination and gathering history. The therapist can ask directly about experiences of feeling or being labeled "off," "odd," "different," "special," "weird," "strange," and other school yard terminology. Once there has been sufficient information gathered to justify a diagnosis, the therapist moves to the second stage of the labeling event.

The therapist may say, "I haven't just been guessing about you. You notice I've been asking some leading questions and seemed to be looking for confirmation of potential behaviors, experiences, and feelings. That's because there's a name for the group of characteristics that you have. People are all over on a continuum of strengths and weaknesses along the characteristics. At certain areas on the continuum, one is really really good at them to being ok or average… or being challenged to really challenged. It's important enough to ones functioning for some people to give it a label sometimes. On the negative side, some people take a label as meaning something is wrong. However, if relevant it can be very positive to make you more successful. We can consider and use other people's research and experiences to either take advantage of issue's strengths and/or mitigate or compensate for challenges of the issues. I think that you might have __________."

Quite often the person may already heard of or assumed the label. Or, he or she may have suspected it. However, the individual may not have known how it had impacted other functioning- especially, relationship functioning. Since labels can be expressed and experienced negatively, the third stage of acceptance versus negotiation of the label may take some time. In fact, the adult individual may have been negotiating against (even in denial) for years and decades. The therapy should focus on the potential benefits of the diagnosis in two ways. One benefit is to shift responsibility (actually, the blame for being unsuccessful or being hurtful to others) from an implied moral or intellectual deficiency to the issue. The second benefit is that the diagnosis can guide more functional and productive behavior. In couple therapy, getting the non-challenged partner to accept the diagnosis as causal or contributing to relationship dysfunction is an additional and critical goal. The non-challenged partner may see a diagnostic label as an excuse for problematic behavior. Handled appropriately the challenged partner loses excuses for problematic behavior. He or she is empowered and held responsible for changing the targeted behavior as appropriate. Successful acceptance of the issue leads to the fourth stage of compartmentalization. Identifying the issue as an aspect and a contributor to the individual's personality, processing, and behavior explicitly asserts the issue's other aspects and contributions. The issue becomes a part of an overall identity as the implicit identity as a failure is addressed and reduced. Once and as problematic behavior is replaced by successful compensations, the fifth stage of transformation begins. Transformation as a more competent individual with growing self-esteem should contribute to transformation in healthier functioning in many realms, including particularly as a partner in the couple.

The following is a chart with the thirteen reasons along with accompanying implied intervention strategies. Following the chart is discussion of ten of the thirteen reasons for missing social cues with brief examinations of how they can impact the couple's relationship, along with guidance for the therapist. Following that discussion will be more expansive information about the final three reasons and their impact on relationships and implications for the therapist: Aspergers Syndrome, Learning Disabilities, and Attention Deficit Disorder (and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder). Many of these reasons have significant cross-relevance to one another, along with strongly influencing emotional, psychological, and relationship functioning and dysfunction. Each issue potentially not only causes problems reading social cues, but also can stigmatize individuals as off, odd, different, or special. Such stigma can increase vulnerability to emotional or psychological harm, life struggles, and problematic relationships.

PHYSICAL DISABILITY - Compensation

Children often creep forward towards the chalkboard when they have difficulty reading the blurry lettering. It is considered disruptive or off-the-wall behavior if the teacher does not about vision problems. When diagnosed and given glasses, they discover they can read the board from the back of the room… without squinting! Individuals often develop intuitive compensations to make up for a physical disability or challenge: tipping ears towards sounds, scanning left to right for limited peripheral vision, or a deeper sniff to distinguish olfactory cues. Intuitive strategies however may be stressful and risk misinterpretation. Unidentified physical disabilities or difficulties, specifically vision or hearing problems can cause missing or misinterpreting social cues. The teacher may have thought a child creeping towards the chalkboard must be disruptive fidgeting! If unaware of gradual hearing loss, a person may be hindered attending to his or her partner's words. That could be interpreted as being uncaring or disrespectful. Getting help for non-visible disabilities however may be stigmatizing, increasing chances of being victimized. Glasses, crutches, or other equipment reveal disabilities, identifying children as different. Unfortunately, receiving extra help in school is predictive of a child being bullied (Carter and Spencer, 2006, p.14). Hidden or developing physical disabilities may interfere with recognizing key social cues in the couple. The therapist should be alert to this possibility not just with older clients but also if there has been undetected deterioration of abilities. An intake form that includes questions about hearing, sight, and mobility may be useful. Identification may be a significant challenge if a disability is not readily apparent. Further complications may arise if ownership of a physical disability becomes an issue of loss for the individual. While glasses were a simple compensation when poor eyesight was diagnosed in childhood, in adulthood systematic examination for physical deterioration or disability may not occur. As a result, there is potential for a lack of diagnosis and thus, an absence of exploring appropriate compensations. While this is not in the scope of practice or scope of competency to diagnose physical disabilities, the therapist should make appropriate inquiries and determine potential influences on relationship functioning.

CROSS-CULTURAL ISSUES - Cross Cultural Education

"Don, you want the last piece of pie?" "No thanks," he replied. So, I ate it! Later, to his girlfriend, he admitted, "I wanted that last piece. I thought Ronald was going to offer it to me again… insist I take it." She laughed, "Nope, with Ronald, you only get one chance!" Don was used to a social-cultural exchange that in response to an offer, called for polite refusal by the guest, polite insistence by the host, repeated polite refusal followed by repeated polite insistence for a couple of additional rounds. Whereupon, the guest graciously accepts! Such propriety around courtesy cues occurs in many ethnic or familial cultures… but not in my kitchen! Don, who is Japanese-American had mistakenly assumed a familiar social courtesy/ritual leading to his accepting the last piece of pie, rather than a literal question, "Do you want the last piece of pie?" He said no, so, I literally ate it! Cross-cultural education regarding social cues, courtesies, and rituals clarifies communication among . This can only occur if one recognizes potential differences in cultural foundations between individuals. Don had assumed that as a fellow Asian-American that I knew the "rules." However, I'm Chinese-American (first American-born of Toishan area Chinese immigrants who were born in the 1920s), while he is second generation American-born of Japanese/Okinawan grandparents or Sansei. Also he grew up on a farm and I grew in in South Berkeley in a black community. For whatever set of life experiences (perhaps, being the fourth of five children and good snacks disappearing quickly in the household!), I had a different set of "rules" than Don. Next time he was over, I offered Don the last piece of a chocolate cake, he immediately responded, "Yes!" Successful cross-cultural education! He now knew my "rules" only because he had stumbled across them. Don may still decline a gracious offer from another host, but in my personal dessert culture, he had become multi-culturally proficient!

Purposeful cross-cultural education promotes learning culturally based social cues among other challenges of diversity. That which was originally perceived as off or strange makes sense from another cultural context. The therapist should explore for cultural models that are less apparent than those more readily recognized visually such as race or gender. Non-race, non-ethnicity, or non-religious shared experiences or challenges may result in distinctive cultures. Deaf culture is an example. "Deaf culture: This term was developed in the 1970s to give utterance to the belief that Deaf communities contained their own ways of life mediated through their sign languages," (Ladd, 2003, p.xvii). Various disabilities abilities, conditions, circumstances, or experiences that may create distinctive cultural attitudes, values, beliefs, and behaviors mediated by common struggles for survival. Cross-cultural exploration and education may become a major thrust of therapy. The therapist can validate the pattern of attitudes, values, beliefs, and behaviors as having served survival demands in previous contexts, and then challenge the individual as to whether they continue to serve survival demands in the new or current context of the couple. The therapist should be careful not to assume that partners that appear to be demographically matched are also culturally matched. There may be significant cross-cultural experiences beyond ethnicity demographics including class, education, immigration, migration, and so on that affect interpretation of cues, communication, and behavior.

OVER-STIMULATION – De-Stress

Too much enrichment becomes counter-productive. Too much fertilizer doesn't help a plant grow, but burns, and cripples it. Cultural or family rules may deny or expect one to hold stress. Failure to recognize accumulation, failure to release, or not knowing how to release stress appropriately creates overwhelmed or over-stimulated individuals with problems recognizing others facial, tonal, or body language cues. An unanticipated unexplained emotional explosion or some form of acting out will look strange. An otherwise calm reasonable person may exhibit odd behavior not normal to him or her when overwhelmed with stress. Individuals can reduce stimulation through cutting back on activities, facilitating stress release, changing the tone and atmosphere of certain tasks, and/or incorporating quiet meditative times. Many individuals engage with their intimate partners when they are already "loaded" with stress: work strife, lack of sleep, chronic illness, financial demands, and so forth. Relatively minor stimulation can become overwhelming: fluorescent lights, tastes, smells, sounds, and dust floating in sunlight. Some individuals because of other issues are more vulnerable to taking in stimulation. For example, Attwood (2006) says that people with Asperger's Syndrome often describe feeling a sensation of sensory overload not readily apparent to others. "There can be an under- or over-reaction to the experience of pain and discomfort, and the sense of balance, movement perception and body orientation can be unusual. One or several sensory systems can be affected such that everyday sensations are perceived as unbearably intense or apparently not perceived at all. Parents are often bewildered as to why these sensations are intolerable or not noticed, while the person with Asperger's syndrome is equally bewildered as to why other people do not have the same level of sensitivity… The sensory system can at one moment hypersensitive and in another moment, hyposensitive" (page 272). While someone with Aspergers Syndrome or some other issue or condition may be predisposed to over-stimulation, challenging life circumstances can have similar effects on others. Overwhelmed people lose focus, becoming more likely to be surprised by circumstances and situations. Relationship demands and distress would add to and be consequential to over-stimulation. The therapist might consider whether it would be useful to initially shift from the couples dynamics to focus on individual self-care improvement and stress reduction due to lifestyle and life demands.

DENIAL – Alleviate Fear

Individuals may find ugly things too much to handle. Losses and pain may be emotionally or psychologically devastating… too much… too intense. Denial is one of the primary defense mechanisms. "NOOO! Yuck!" involves refusing to ingest the "poisonous" feeling, idea, or perspective. "When people are confronted with circumstances they find to be a threat, they often deny association or involvement with any aspect of the situation. Young children are often caught in the act of lying (denial) when they are accused of eating cookies right before dinner or making a mess in the bathroom. Examples in adulthood include denying a drinking or gambling problem. Any stimulus perceived to be a threat to the integrity of one's identity can push the button to deny involvement or knowledge. At a conscious level, the person truly believes he or she is innocent and sees nothing wrong with the behavior" (Seaward, 2006, p.84-85).

Social cues are purposely ignored or denied. Or, semi-consciously or unconsciously ignored or denied. Recognizing that someone is uncomfortable or unhappy with oneself may require acknowledging something too challenging: feeling embarrassment, realizing that one can't please everyone, risking being wrong or getting into trouble, or admitting "uncoolness." To another person who does not have the same underlying feelings or issues, denial is nonsensical, completely off or odd, or strange. Masculine codes to fix or problem-solve that are frustrated by insurmountable challenges may require denial rather than accept failure as a man. Denying having some disability or challenge can come out of fear of being declared "weird" or "messed up." Suffering victimization is preferred rather than admitting ones impotence or being a "wimp," a "doormat," or other derogatory label of helpless victimhood. Suffering in silence becomes the outcome of denial. Denial, however keeps individuals isolated even when involved with an intimate partner. It increases vulnerability to being victimized, depressed, and isolated. The therapist needs to remove the option to suffer in silence. Intervention needs to happen with or without the "permission" of the victimized or depressed, an assertion of support for mature commitment to healthy life and opposition to giving up. The therapist's confidence and skill in naming and addressing an individual's fear offers to the individual a means to resolve it through processing rather than avoid it through denial. The individual finds strength, skills, and resiliency in the process and alleviates his or her fear. Within the couple's relationship, when the therapist can appropriately facilitate facing a previously denied issue safely and successfully, he or she models the process for the couple to consider repeating for other issues. If it is the partner's needs, feelings, or issues that must be denied, then the relationship suffers harm for the betrayal of failing to offer support. The therapist should also consider if the partners in a couple have colluded to deny some threat to the relationship. That might be alcoholism, the death of a child, financial irresponsibility, an affair, the paternity of a child, mental illness, or some trauma. They may fear that admitting some element would destroy the relationship and thus, chose not to talk about it… including talking to the therapist about it. Revealing or confronting such a secret may be essential to therapeutic change.

ANXIETY – Stabilize/Secure

"What? Where? Watch out? Where? Now?!" While fear has is specific (afraid of snakes, of heights, etc.), anxiety develops without a specific source or object to fear. Therefore, anxiety is without specific remedy. One can remove snakes or avoid heights or work at getting used to snakes or heights- systematic desensitization or exposure treatment. However, one cannot remove vague amorphous sources of anxiety. Reassurance, support, plus positive experiences and outcomes do not relieve habitually anxious people. Normal anxiety is time-constrained to facilitate identifying and responding to immediate demands. Anticipating foreseeable issues, normal anxiety prompts scanning for social cues to others mood and intent. However, over-anxious people, with deep senses of vulnerability and experiences of chaotic and unpredictable lives stay in constant states of anxiety. They become hypersensitive and hypervigilant. Hypervigilance expends energy scanning unnecessarily in relatively benign situations. Hypersensitivity interprets neutral environmental and social cues as threatening. Anticipating ominous cues, individuals err being over-cautious and overly negative. Creating predictable, stable, and secure home environments and facilitating predictable interactions and relationships reduces anxiety.

Challenges or disabilities may exacerbate any environmental causes of anxiety. Any and all of experiences caused by the other reasons for missing social cues can add to anxiety. Prior failures make them hypersensitive and hypervigilant to new frustration. For example, Connor (1999) describes this dynamic with Aspergers children. "Problems with 'tolerance' include a sensory and emotional over-sensitivity, such that feelings are sometimes overwhelming even if they cannot be expressed or even understood, and a fear of other people or of being found unable to know what to do… there may be a focus upon a particular interest at the exclusion of all others, an acute anxiety (albeit irrational) about a range of stimuli, and a possibility that other people's words or actions can spark off some unintended action."

Challenged individuals are often unaware of how their challenges affect perception and functioning. They are often unable to alter behaviors and thus, experience bad things happening repeatedly. Anticipation re-ignites anxiety, often intensifying negative behaviors. Further failure exacerbates the anxiety-failure-anxiety-failure cycle. Resultant behavior may destabilize the environment, frustrating others and heightening anxiety for everyone (including the already anxious individual). While maturity may lead to greater understanding of cause and effect and relative security, habitual anxiety may persist into adulthood. Anxiety in the couple's relationship can distract from accurate attention to social cues. Intervention must include accurate identification of how individual's challenges create anxiety. The therapist should promote processes to alleviate such anxiety and increase success. Therapy may need to address historical anxiety from the family-of-origin along with promoting predictability and consistency in the couple's relationship. The therapist may need to focus the anxious individual on the relevant social cues the partner is presenting. The therapist should get the anxious individual to empower his or her partner to point out relevant social cues or key messages if they are missed.

NEUROSIS – Reality Filter/Check

"Here puppy puppy." Pheromones emit. "Hi puppy," slowly reaching a hand to pet the dog. The dog cringes reflexively and snaps at the hand. All intentions and cues given indicated the person was not dangerous. But the dog's first master had reached down and smacked it… many times over and over. The dog misinterpreted the person's gentle cues as "Here we go again," another smack on the head. Instincts and intuition, based on prior experiences alter perception when interpreting cues and predicting current or future situations. Neuroses come from very negative prior personal experiences. As personal experiences, neuroses are unknown to other people including the partner. If he or she does not reveal the neuroses- either being unaware or holding them secret, then neurotic-based behavior appears from odd to crazy to others. Neuroses are anxious assumptions that previous bad outcomes are applicable to new or current people and situations. Unfortunately, the logic is outside the awareness of others who see it and often outside the current context for the individual. The individual is automatically alerted, "Hey, what's that?" And then cringes reflexively, snapping back verbally. Prior severe criticism from upset powerful individuals anticipates severe punishment from an upset but non-punitive and nurturing partner. Similar misinterpretations may occur when receiving the partner's social cues of aggression, discomfort, anger, and so forth. The individual needs an abundance of new positive reparative experiences to countermand the impact of previous abundant and/or intense negative experiences. The therapist needs to facilitate the individual doing frequent reality checks regarding cues and behaviors of the partner to counter neurotic filters. Neurotic reactions include:

being defensive, "I didn't do nuthin'!"projection, "You're the one who's mad!"misinterpreting intent, "You're always being mean to me!"making accusations, "You never let me talk!"

Since one's personal history often includes negative experiences, reality filters may initially target refuting the absolute modifiers: "always," "never," and "all the time," and contesting the assumption of unjust repetition conveyed by the word, "again." Absolute modifiers anticipates inevitable doom. "Again" implies repetition of injustice, rather than behavior being reasonable or consequential to current circumstances. "Again" also ignores responsibility of the complainer for current circumstances. Accepting partial influence, power, and control mitigates negative consequences, countering neurotic doom. Learning choices, in addition to recognizing neurotic interpretations interrupt the neurosis. When the individual can recognize doom thinking,

"It must be… I will be… They must be going to… always… never… all the time…"then, he/she can substitute,"It might be… I might be… They might be going to… or not! Sometimes… too often…"

"Must" asserts neurotic interpretation as reality. "Always," "never," and "all the time" deny the possibility of other interpretations and assert unalterable past, current, and future duplication. "Might," on the other hand prompts examining neurotic assumptions for reality. "Sometimes" and "too often" asserts displeasure without doom. Hope is allowed! These words acknowledge positive experiences, and implies the possibility of increasing positive frequency while decreasing negative frequency. Victimized individuals often become unreceptive to being empowered if caught up in expecting inevitable doom. Reality may include previous and even frequent victimization, but neurotic interpretation expands helplessness across individual's complete experience: past, present, and forever. Identifying even limited power, control, and competence versus neurotic self-definition as helpless is a critical first step to empowerment and change. This could be explored from a variety of theoretical and therapeutic orientations: developmental, attachment, family-of-origin, psychodynamic, feminist, and so forth. Therapy would focus on connecting prior cues and experiences to what is triggered in the present, and then exploring the resultant emotional and psychological consequences.

DISASSOCIATION – Trauma Work

"Click… This station is no longer broadcasting…or receiving." Denial is cognitive blocking of intolerable experiences or feelings. Neurosis is anxious interpretation that things will turn out badly again. Disassociation on the other hand occurs when experiences are too devastating to be endured or felt. Unconscious processes can turn off memory, disconnect from feelings altogether, or attempt to block response to triggers or stimulation. Singular devastating incidents or enduring/ongoing experiences in the present or in the past, witnessing or experiencing horrific violence or chronic physical, sexual, or emotional abuse, may render feelings or thoughts beyond conscious tolerance. Disassociation is a trauma response. It is an extreme response to extreme anxiety beyond the outer edges of human capacity to endure danger or threat. If triggers or stressors are similar to those of an original trauma, emotional, cognitive, and psychological circuit breakers turn off in the face of anticipated re-traumatization. Rather than flight or fight, traumatized individuals freeze facing perceived danger. When disassociated, beyond missing subtle social cues, even more obvious communications are missed. The lights are on, but no one is in. The partner may be there physically, but there is no response or some robotic empty reaction. Individuals may have traumatic experiences from previous experiences and/or chronic victimization that can trigger disassociation to stimuli other individuals normally handle readily. Stressors extend beyond academic and/or social requirements in childhood to work and other adult demands. The therapist can help individuals and couples identify and subsequently anticipate potential triggers such as conflict situations, holidays, anger, media scenes of violence, and so forth. Getting history of traumatic experiences from the individual and his or her partner helps identify potential triggers.

INTOXICATION/SUBSTANCE ABUSE – Sobriety

Intoxication or substance abuse assessment should include consideration of pharmacological medication. Medication that has either a sedative or a stimulant effect may affect alertness and focus. Cough medicine may include chemicals such as Dextromethorphan to relieve coughing, with possible side effects including dizziness, lightheadedness, drowsiness, nervousness, and restlessness (MedlinePlus, 2008). Albuterol (brand name-Ventolin HFA), an asthma medication, for example may have a stimulant effect on some individuals. The following precaution is listed on the manufacturers website, "Common adverse effects of treatment with inhaled albuterol include palpitations, chest pain, rapid heart rate, tremor, and nervousness" (GlaxoSmithKline, 2008, p.7). The therapist needs to be aware of any medication taken that may cause unanticipated attention, hyperactivity, or other problems, and should note and inform clients of any behavior changes. Cognitive, emotional, and psychological processing and interpretation of cues can be compromised by mind and mood altering drugs, whether recreational or prescribed… legal or illicit. Restoring sobriety would be the intervention. Individuals suffering emotional distress, may access alcohol, over-the-counter drugs susceptible to abuse, and recreational illicit drugs to self-medicate. Giedd (2003) surveyed research and found the diagnoses of ADHD and substance abuse occur together more frequently than expected by chance alone. The National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University (2000) examined the link between learning disabilities and substance abuse and found, "…adolescents with low self-esteem may use drugs for self-medication purposes--to counter negative feelings associated with social rejection and school failure… Some specialists believe that people with ADHD medicate themselves with drugs such as alcohol, marijuana, heroin, pain medication, caffeine, nicotine and cocaine to counter feelings of restlessness" (p.9).

Self-medication occurs among many depressed individuals. Challenged individuals may turn to alcohol, substance abuse, or other self-medicating behaviors to counter painful experiences such as overwhelming stress, depression, and anxiety. Self-mutilation- cutting for example can be considered a form of self-medication. The physiological response to self-inflicted injuries activates a whole canopy of chemical responses, including numbing not just physical pain, but painful emotions. Timofeyev, et al (2002) suggests that in addition to dopamine, "endogenous opioids have also been linked to self-mutilation. The biological reinforcement theory suggests that the pain from self-mutilation may cause the production of endorphins (endogenous opioids) that reduce dysphoria. A cycle is formed in which the habitual self-mutilator will hurt themselves in order to feel better." Self-medication can be essentially behavioral- behaviors that allow one to forget or to avoid intense feelings: workaholism, excessive and compulsive exercising, or thrill seeking behavior. Behavioral compulsions can also activate biological processes for emotional self-medication. Many people including partners often misinterpret individuals' use of alcohol and drugs (especially marijuana) as purely recreational or a sign of negative values. Partners may use alcohol and drugs to self-medicate for the depression, anxiety, and stress from both inside and outside the relationship.

Individuals who self-medicate with alcohol become disinhibited, which can result in a myriad of atypical behaviors otherwise inhibited when sober. The behaviors may be a bit strange to bizarre or just out of character. Individuals may engage in dangerous activities that are highly stimulating- the stimulation help block out intense negative feelings. Recent research says that compulsive behaviors create chemical changes within the body that function to change sensation and feeling (they activate the body's own self-medicating chemicals). Eating disorders may also be ways to avoid intense painful feelings. An anorexic's intense feelings of hunger or/and compulsive overeater's intense sense of feeling bloated can serve to block out painful emotional and psychological feelings. Chocolate or shopping can also give you a "high" to serve to block out feelings. The therapist should assess for both substance (legal and illegal, over-the-counter and prescription) and behavioral self-medication. The bio-chemical effects may be either or both a response and a cause of relationship problems. Attempts to self-medicate can interfere with attention and response to partner communications. The therapist may find an individual in denial about his or her substance or behavioral self-medication, but be able to gain perspective from the partner's observations and perspectives of the individual. Or, the partner may not be aware of the self-medicator's use of substances or behavior to deal with relational or life distress. The therapist should be alert to complaints about a partner's behavior such as spending money, watching sports, or surfing the internet may actually identify some form of self-medication. Problem-solving focused only on reducing the negatively identified behavior could be misguided therapy as a result.

SCHIZOID PERSONALITY DISORDER – Behavior Training

People with schizoid personality disorder (APA, 1994, p.638) recognize social cues correctly, but are indifferent to most common social processes. Schizoid individuals do not seem to enjoy, miss, or desire relationships or personal intimacy, and are generally unavailable to motivation other than perhaps behavior training. Per the social and intimacy driven standards of modern culture, individuals with schizoid personality disorder are classically off or odd. They do not want what everyone else wants or may even be desperate for. "Individuals construct their lives to limit interactions with others and usually select occupations that require minimal social contact and are sometimes in jobs that are below their level of ability (Beck & Freeman 1990). They have a tendency to turn inwards and away from the external world (Kalus et al. 1993) and see themselves as self-sufficient and independent and will sacrifice intimacy in order to preserve autonomy (Beck & Freeman 1990). They consider themselves to be observers rather than participants in the world around them. Some typical thoughts may include: 'going through the motions', 'why bother', 'who cares', 'rather do it by myself', 'emptiness inside', and 'life is unfulfilling' (Beck & Freeman 1990)" (Hayward, 2007, page 17).

A schizoid individual avoids life challenges, is intolerant of life's ambiguities, finds the world threatening, and seeks always to be "right" (not to be wrong) and be in control. He or she actually feels very inferior and incompetent, and thus tries to refuse participate in the world. "The SPD is driven not so much by motives of power over others as by retreat, justified as indifference, contempt, and disinterest toward others, social rules and conventions" (Slavik et al., 1992, page 144). Rather than missing social cues or other messages, the schizoid individual asserts not to be interested or invested. Instead of being aggressive, he or she pulls away. "They tend to view themselves as unwanted, misfit, or wrong, and arrive at 'I'm a misfit from life so I don't need anybody. I'm indifferent to everything.'" At some deeper level, the schizoid individual may wish to have a "normal" life, but recognize that he or she cannot respond as others and become emotionally attached to animals or inanimate objects. Other people including a potential partner might experience the schizoid individual as "shy, withdrawn, reclusive, isolated, dull, uninteresting, and humourless. Their cognitive style is characterized by vagueness and poverty of thought or concrete thought form. Typical behaviours include lethargic and unexpressive movements that lack gestures or alternatively, rhythmic movements, slow and monotonous speech, poor spontaneous speech, or poverty of content of speech, limited eye contact, and may appear ill at ease (Beck & Freeman 1990). Although they may appear sad or anxious during close encounters, they are not inclined to show their feelings either verbally or through facial expressions (Beck & Freeman 1990; Carrasco & Lecic-Tosevski 2000). Excessive over- or understimulation may leave these individuals vulnerable to axis I disorders such as anxiety when situations demand social interaction. Depersonalization may occur because of limited contact with, and emotional distance from other people. Others may experience a distorted sense of themselves and their environment. Reduced social contact may result in an increased fantasy life and possible brief psychotic or manic episodes as a reaction to a perceived meaningless existence (Beck & Freeman 1990)" (Hayward, 2007, page 18).

Individual therapy would focus on reducing isolation and establishing a sense of intimacy. The therapist and anyone pursuing a relationship with a schizoid individual may risk pushing the individual in ways that may become intolerable. The therapist needs to be sensitive and tactful to support the individual's differences and the development that has made vulnerability intimacy difficult for him or her. Since the schizoid denies needs for intimacy and tries to protect oneself conflicted by relationships as too close or too far away, interactions activate the "master-slave object relations unit, or too far, activating the sadistic object-self in exile unit. The patient with a schizoid personality disorder, as with the borderline and narcissistic disorders, also enters treatment incapable of a true transference relationship. Rather, this patient, too, will be transference acting out his or her intrapsychic structure (Klein, 1995, pp. 72-84). That is, in accord with the individual's inner psychic architecture, the therapist is perceived as either the `master' or as the `sadistic object'" (Roberts, 1997, page 242).

The schizoid sees the therapist (or any potential intimate) as controlling, dominating, and wanting to abscond with anything valuable. Being enslaved is the result of a relationship and to be avoided. This preconception leads to isolation but simultaneously keeps one emotionally safe and avoids manipulation. A potential partner may not have sufficient awareness of the schizoid perspective to be sensitive and tactful. Attempts to be in contact will likely increase anxiety. The schizoid individual may desire for quick symptom relief, not be responsive to praise, and have difficulty establishing a relationship (Hayward, 2007, page 18). Treatment may be directed at dealing with specific problems in daily functioning. Long-term change is difficult given individuals' apparent disinterest. This reason for ignoring rather than missing social cues is problematic in terms of couples. It would seem unlikely that someone with a schizoid personality disorder would enter into a couple's relationship. When in a long-term relationship, the schizoid partner seems not to really desire or enjoy intimacy. He or she may find a partner who accepts little or no intimacy and who facilitates the schizoid partner staying at an emotional distance. Openly or covertly the partner rejects the schizoid partner and supports and encourages him or her isolating him/herself.

"If the SP seldom expresses strong feelings, such as anger or joy, a partner will claim to be afraid of anger and offer no reason for the SP to be joyous in the relationship. Such expressions will be undermined in the details of the transactions which occur between them. If the SP has little sexual desire, a partner will be compliant with that, any claims to the contrary notwithstanding. If the SP is indifferent to praise and criticism, it may be that the partner uses the former manipulatively and/or floods the SP with the latter, so that is easier to retreat (especially if that is a well-known style). In short, the SPD is reinforced by partners who may clamor for more and use the SP's behavior as an excuse to withdraw from contact" (Roberts, 1997, page 241).

Having become part of a couple, the schizoid individual may not have done so for emotional intimacy. Joining in a partner relationship would likely be for some other functional purpose: finances, power, safety, advancement, and so forth. As such, he or she would be unlikely to have instigated couple therapy to gain intimacy that never mattered in the first place. The problem for a schizoid individual is that being in a relationship may seem to require being submissive, dependent, compliant, and being victimized. The partner may be perceived as controlling, coercive, and appropriating of the self as expressed in the master-slave unit. On the other hand, staying safe by not being in a relationship is like being isolated in exile with deep loneliness as expressed in the sadistic object-self in exile unit. "The options, then, based upon the intrapsychic structure of the schizoid individual, are relatedness and loss of self or safety of the self in exile and intolerable isolation. This, then is the `schizoid dilemma', both being too close and being too distant result in activation of the abandonment depression" (Roberts, 1997, page 241).

It seems unlikely that most individuals would accept or enter into a relationship devoid of intimacy unless there are other compelling reasons. In addition to the functional purposes for the schizoid person to enter into a relationship, it may be possible or probable that the non-schizoid partner had some significant complementary characterological psychological dysfunction. The therapist would need to ascertain what may be the functional contract or expectations for each partner. Therapy may need to work within the boundaries and limitations of their agreement. Emotional, intimacy, or attachment oriented therapeutic processes may be ineffective- essentially, irrelevant to the couples expectations. The therapist may find him or herself acting more as a business negotiator or mediator to repair a quid pro quo relationship where feelings have little or no relevance. A hypothetical alternative situation would find the therapist working to maintain a fundamentally dysfunctional relationship- that is, helping a psychologically needy and damaged partner and a psychologically flawed partner co-exist. While the schizoid partner would accept a functional relationship without emotional intimacy, the other partner would have to learn to accept a persistently unfulfilling emotional relationship. The other partner would either accept never getting what he or she desires, or be coached to hold false hope that somehow the schizoid partner will change. The therapist may find him or herself unable to hold false hope that the schizoid partner will change or the non-schizoid partner will find sufficient self-esteem to leave the relationship. The therapist may find this an untenable therapeutic goal that goes counter to his or her professional integrity. If this proves to be so, the therapist may have few or no alternatives except terminating the couple therapy.

PSYCHOSIS – Stabilization

A nervous breakdown used to be called vapors, melancholia, neurasthenia, neuralgic disease, or nervous prostration. Clinical diagnoses found in the DSM-IV (APA, 1994) include psychotic break, schizophrenic episode, manic break, post-traumatic stress disorder, panic attack and major depressive episode. When psychotic or delusional, individuals respond to internal cues in addition to cues from the physical environment, causing gross misinterpretation of non-verbal cues or anything else. Extreme stress, depression, anxiety, fear, mania, trauma, substance abuse, or medication side effects or complications can cause breakdowns, temporary psychosis, or delusions. Individuals can often stabilize back to normal functioning. Some breakdowns precipitate deeper and permanent mental and psychological disabilities. Psychopharmacological intervention has become the dominant treatment for long term or ongoing psychosis. It has been applied with and without psychotherapy or milieu or social treatment. There may be differential psycho-medication approaches for transitory, episodic, recurrent, versus long-term psychosis. Medication treatment has proponents and detractors. Psychopharmacological intervention or advice is also outside the scope of practice and scope of competency of non-psychiatric psychotherapists. Relative to couple therapy, treatment is essentially the same as with an individual alone- stabilization of the individual to functioning without psychosis and maintenance of the individual to prevent relapse of psychosis. Missing social cues, unfortunately hardly begins to describe the problems of a psychotic person or being partnered with one.

Wylma and Gianna had a long relationship with what Gianna described as normal drama and conflict. However, things had progressively gotten worse the last two years. Wylma had problems with depression over several years. She had been abused as a child and experienced further trauma while serving in the military. Gianna said that Wylma could be a wonderful partner, but her mood shifts were becoming more intense. Wylma had been under psychiatric treatment for depression with a variety of medication. Sometimes, the meds seemed to be effective, but they didn't stay effective for long. In fact, she had started having the mood shifts after she began a different regime of anti-depressants about two years ago. She would get hyper and "a different person" that was alternatively animated and angry. That Wylma scared Gianna. When Gianna called, they had just had a horrific argument where Wylma had accused her of lying to her and belittling her to their families. The therapist advised Gianna to make sure that Wylma was safe and that there was no danger to her, anyone else, and Wylma. In addition, the therapist speculated that Wylma was decompensating psychologically. Gianna wasn't sure what a psychotic break was, but she was so erratic. The therapist advised her to get Wylma examined by a doctor or psychiatrist if possible. And that if she felt threatened or Wylma was at risk to hurt herself, to call the police or otherwise make or force her into care. Giannasaid it wasn't like that… yet. Gianna was not sure if Wylma would come to a session, but set one up for the next day.

When Wylma and Gianna came to therapy, Wylma seemed agitated. She fidgeted in her chair, spoke with great intensity while stumbling over her words, and glared at Gianna periodically. She accused Gianna of having humiliated her over and over with friends, of disrespecting her in front of family, and calling her stupid and lazy. Gianna teared up while denying that she ever or would ever be so hurtful to Wylma. She repeatedly asserted how much she loved Wylma and wanted to be supportive, but didn't know what had happened to her. Wylma continued to be agitated and accusatory. The therapist attempted to do reality checks with Wylma, including questioning the illogic of some of her accusations. "If Gianna despised you so much, how come she continues to want to be with you?" Wylma continued with the same assertions. When discussion shifted to her childhood abuse, Wylma became very sad and tears came to her eyes. She began crying into her hands. When Gianna reached over to touch her, she accepted it. The therapist asked Gianna if Wylma became despondent other times. Gianna said she did… and more deeply than previously. It was hard for Wylma to not sink deeply into self-hatred and despair and just about impossible for Gianna to do or say anything to reach her.

Almost any therapeutic strategy from couple therapy theories was largely irrelevant for Gianna and Wylma. Wylma was almost certainly having a psychotic break, was delusional, in the midst of a manic phase, or having a drug or medication-induced breakdown. She could not be present emotionally or intellectually for therapy, much less interact with any coherence with anyone. The therapist recommended to Gianna and Wylma to seek out immediate medical and preferably, psychiatric attention. Hopefully, Wylma would voluntarily hospitalize herself, but the therapist encouraged Gianna to institute an involuntary hospitalization if necessary. The session terminated with Wylma saying that she was willing to go to the hospital and Gianna committed to getting her help. At the time, Wylma was not an imminent danger to herself or to anyone else. The therapist had asked Wylma if she would hurt herself or if she might hurt someone else and Wylma responded that she would not do either. The therapist made a therapy appointment to see Gianna (or Gianna and Wylma depending on what transpired in the next few days) and a phone appointment to talk with Gianna to check in on Wylma's status (hopefully, her hospitalization). Couple therapy or what can be done under any name would consist of supporting Gianna to arrange care for Wylma. Emotional, psychological, intellectual, and spiritual stability is necessary to forming an intact consistent identity and personality to present to another person when attempting to develop a relationship. Wylma had that stability previously but become unstable and hence, her and Gianna's relationship became unstable. Who and what she was had become too volatile for Gianna have any sense of consistency or predictability in the relationship. Any relationship where either or both partners are unable to maintain a solid self to offer to the other loses viability. For the same reasons, a therapeutic relationship at this point also lacked viability. For some individuals, it is a developmental issue. Maturity along with experience will suffice to create a solid self for relationship. For others, emotional or psychological issues need to be resolved before a solid self develops. Psychosis may be the epitome of an erratic self as opposed to substance-induced characterological shifts or stress-induced mood changes.