3. Treatment Plan - RonaldMah

Ronald Mah, M.A., Ph.D.

Licensed Marriage & Family Therapist,

Consultant/Trainer/Author

Main menu:

3. Treatment Plan

Therapist Resources > Therapy Books > Out Monkey Trap- Breaking Cycles Rel

Out of the Monkey Trap, Breaking Negative Cycles for Relationships and Therapy

Chapter 3: TREATMENT PLAN

by Ronald Mah

Rhodes suggests a treatment plan that incorporates various principles and techniques of strategic theories. The therapist who may not align or identify as a strategic therapist may find that strategies and elements of the treatment plan reflect his or her work with couples.

(Rhodes, 2008, page 38).

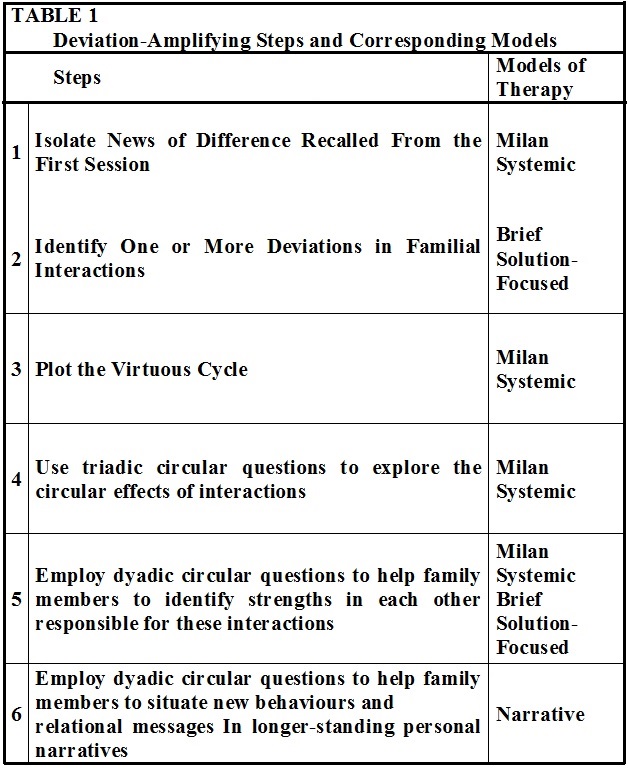

In the treatment plan, Rhodes identified the models of strategic therapy for each stage of the plan. "The nine steps… provide a template to assist the therapist to amplify small deviations in family interactions after the first Post-Milan interventive interview. This is achieved through the rigorous contextualisation of a small deviation, in a sequence of interactions, in intentional efforts to enhance relationships, in a series of strengths-based and preferred narratives and in the history of these preferred narratives. The amplification process is then extended into the future, thus allowing for the self-selection of specific systemic tasks" (Rhodes, 2008, page 38-39). The following are the nine steps adapted to working with a couple as opposed to a family, along with descriptions of how they are applied to a specific couple.

Step 1: Isolate First Session News of Difference

The first step is to reconnect the individual, each partner, or each family member to the feedback offered by the therapist in the first session or sessions. This primes the individual, couple, or family to be open to questions about change and can discourage the presentation of new problems, or the re-enactment of behaviors that are part of relationship vicious cycles. The therapist might ask each individual:

Can you tell me one thing that most interested you from the feedback last session?What in particular caught your attention about these comments?

The therapist chose to focus entry into the family system and problems through the couple. The children were sent home and therapy continued with just Genevieve and Dillard. There was periodic focus on one or the other child's behaviors and the two adults were coached in co-parenting strategies and techniques. Getting the co-parenting process between them in sync aided their overall relationship. However, therapeutic focus was on their relationship and dynamics. Dillard mentioned that he was intrigued by the therapist's challenge that he tended to catastrophize Genevieve's behavior. The therapist had validated Dillard's upset at feeling that he did not matter when he did not hear from her. However, the therapist had added that given her sincere efforts to improve, Dillard seemed to resist being reassured. The therapist had pondered out loud, if he had prior experiences of being discounted that made this so sensational. Dillard had been thinking about what that might be. The therapist had asked Genevieve if there was something about her process that caused her to be slipshod about a value and behavior she shared with Dillard about good communication. Genevieve had acknowledged that Dillard's request to be notified in a timely fashion of schedule changes was very reasonable. Yet, she had trouble following through. Genevieve had been wondering if this happened just with Dillard. She had come to the conclusion that she had this problem… did this sometimes with others too. She was considering if it was some family modeling or perhaps, some learning disability or style that she was not in control of.

Step 2: Identify Deviations in Familial Interactions

Individuals, partners, or family members should then be asked to recall any small changes in the presenting problem or interactions since the last session. It may be useful in couples and families to ask first the partner or member who is most likely to recognize these small changes. The therapist can ask one or more of the following questions:

Has there been any time in the last two weeks, when you thought (the presenting problem) would happen, but it didn't?Has there been any time in the last two weeks where you thought a change (in interaction or relationship identified in the first session would happen, but it didn't?Have you noticed you or your partner or family member doing something slightly different in their interactions in the past two weeks?

Dillard said that Genevieve was about ten minutes later one day last week than the twenty minutes late she had said she'd be when she called. He had started to get upset, but had slowed himself down enough to remind himself that Genevieve was trying to be better. As it turned out, there had been a car accident on the way home that had blocked traffic that made Genevieve late. When she got home, as Dillard had waited to let Genevieve tell him why she was late, he realized that he was ready to be mad at her for dismissing him again. He was able to let that pass. Genevieve had been congratulating herself as she left work. She had realized that she was going to have some extra things to deal with before leaving earlier in the day. Ordinarily, she would tell herself that she had time (literally in this situation, the whole afternoon) to call Dillard and let him know she'd be running late. Thus, she would not have an urgency to call him right away. She had realized that often times when she did this, she would get so wrapped up in the hubbub of work that she would forget to call. This time she had called right away and told Dillard that she expected to be fifteen to twenty minutes late. Genevieve had been very conscientious and was able to block herself from taking on another task (another process vulnerability for her) and had actually left about five minutes earlier than expected. But as luck would have it, the car accident in the road had made her late. Other times, when she had come home late, she had not bothered to explain to Dillard. He had been very supportive of her business and seemed accepting of how it challenged her time wise. She had assumed he would understand. Since they had discussed this in therapy, now she knew that it mattered to him. Somewhat from anxiety that he would be upset, but more to acknowledge him, Genevieve told Dillard right away what had happened. With the therapist prompting, Dillard and Genevieve identified several things that they each did differently from before.

Step 3: Plot the Virtuous Cycle

The aim of Step 3 is to help the individual, couple, or family position one of these deviations in a wider context of interactions. Small changes in behavior should serve as one step in a sequence of interactions that may have occurred over an hour, a day or the entire week. The therapist should aim to plot this sequence with the client in detail, avoiding any attempts to generalize, focusing instead on developing a consistent view of actual events across the relevant time period. The therapist can ask questions such as:

Can you tell me about this example in more detail?If I had been a fly on the wall at your house, what would I have seen happen as a lead-up to this example?What happened next?What happened after that?

The therapist continued to prompt Dillard and Genevieve for information until a distinct pattern emerged. The pattern that emerged involved Genevieve getting caught up in her work, having difficulty setting boundaries for herself. She tended to respond immediately to something rather than ascertain whether it can be done at another time. Subsequently, she would lose track of what is not immediately in front of her. Since there is a transition from work to home, Dillard is not normally "right in front" of her until she gets home. Another part of the pattern or Dillard's pattern was an expectation or need for some response to Dillard from Genevieve. Dillard would have some anxiety that he would not be attended to or noticed. This may have been a part of a childhood and family pattern of Dillard's as yet unexplored. Dillard would amplify the anxiety into anger based on anticipating being neglected again. Once in that emotional state, Dillard would react hostilely to Genevieve. She would be offended but try to placate him to avoid a big fight. They would both end up with resentment: Dillard would have resentment because her placating him did not address his needs. Genevieve would have resentment because her need to placate blocked her sense of injustice for being impugned.

Step 4: Use Triadic Circular Questions to Explore Circular Effects

The therapist should then develop with the individual a richer view of these interactions, exploring the relational messages that individuals were giving through new behaviours and the effects of those messages on recipients. One person is asked to explore the meaning of an interaction. The other person is asked what the interaction means as well. In the case of someone in individual therapy, his or her other personas or conflicting opinions or feelings are voiced. Gestalt work having the individual sit in different chairs and speaking from the separate personas, views, or emotions may be useful. The individuals or personas are prompted to respond in turn repeatedly. This circular enquiry may be employed especially with a variety of triads, depending on the number of family members, the nature of the sequence and the potential significance of interactions. For example, the therapist can

Ask person A the following and then check person A's impressions with persons B and C:If I asked person B what message he was trying to give to person C what do you think he would say?If I asked person B what his intentions were in interacting with person C in this way, what do you think he would say?If I asked person C what effect person B's behaviour had on him, what do you think she would say?How important do you think person C would tell me this was to her?

In individual therapy, persons A, B, and C can be the cautious persona, the risk-taker, and the problem-solver or logical part of the individual. If the therapy included other family members, the therapist could use triadic circular questions. For example, Genevieve and Dillard brought their sixteen year-old Geoff in for a session because he was throwing tantrums about going to bed early on school nights. The therapist asked Geoff what happened with him when it was time to go to bed. After he described wanting to watch more television, text message his friends, play video games, and surf the internet after doing homework. He deserved the relaxation time after doing the homework, the therapist asked Genevieve and Dillard respectively what each of them experienced. When Genevieve talked about what she was trying to do with Geoff, the therapist checked with her about what she was trying to communicate to him. The therapist asked Geoff what his mom did and what he thought she wanted. Dillard was asked what he thought was going on. The circular questioning kept checking and re-checking if intention and reception matched and what the consequences were. With just the two partners, the therapist can use circular questions using him or herself as the third character in the triad. The therapist asked each in turn, "How do you think I interpreted what you said? What were you trying to get with me?" The therapist can speak from his or her counter-transference experiences about what he or she interpreted or experienced. And, then refer to one or the other person, partner, or family member to reflect on that might be or mean. For example, the therapist in reference to their communication issues asked, "Dillard, when you correct Genevieve about the details of what she's talking about… telling her the exact time she said she'd come home, what do you think I'm thinking?" Or, "Genevieve, what was that comment about the new employee at the business supposed to mean? What did you want Dillard to get or do?"

Step 5: Help Family Members Identify Strengths in Each Other

Once a specific sequence and the relational messages have been identified they can be further amplified by asking the individual, partners, or family members to identify the strengths in each other that made the new behaviours possible. The therapist might ask

Ask Person C, 'How do you think person B managed to interact in this way on this occasion?What advice do you think she was giving herself?What strengths do you think person B was relying on in interacting in this way?Ask Person C, 'What was it like for you to hear person C's impressions about what you did?

The therapist asked Dillard, "What do you think is going on with Genevieve nowadays when she's late? What is she trying to do… what does she expect of herself about being on time?" The reference to the current situation is important in this case because of the mutually acknowledged improvement on Genevieve's timeliness. If Dillard speaks negatively to the prior times when she was not as timely, the therapist should refer Dillard to the recent times where there positive behavior indicative of some strength in Genevieve. "That's what she used to do. You just said that she was much better lately… this week, for example." The therapist can ask Genevieve, "Dillard used to go off on you when you were late… not waiting for an explanation. How is he now?" The therapist can be more direct by asking the partners specifically, what is the other doing differently or better. "Why do you keep trying with him or her?" often elicits what each partner sees as the strengths and positives in the other that makes trying worthwhile. Dillard and Genevieve commented on each other's commitment and continued efforts as strengths.

Step 6: Integrate Family Member's New Behaviours with Their Preferred Stories

Changes in behaviour can also be amplified by engaging in conversations that demonstrate how those changes are consistent with the person's preferred identify and values, and with the preferred story of their life to this date. The therapist might ask

What does it tell you about him or her as a husband (or wife, or son or daughter… or friend, colleague, or boss)?What does it tell you about him as a person?How do you think it relates to his values or what he feels is important in his life?Can you tell me some other examples in the past of when he has demonstrated these qualities?Is there any one particular experience in his life that most contributed towards the development of these qualities?

The therapist reframed Dillard's complaints about Genevieve being late to what expectations Genevieve had of herself. "You said you mess up with time. But don't have any intentions to be dismissive of Dillard's feelings. That's not the partner you want to be." This prompted Genevieve to talk about wanting to be attentive, nurturing, and respecting as Dillard's partner. She spoke about how important that was to her because of experiences she had where intimate people failed her. She was appalled that Dillard thought she might be indifferent to his feelings. When Dillard was asked about what hearing this meant to him, he said it helped him understand she had time management problems but it was not because she did not care about him. When prompted Genevieve brought up times when she had made a point of being attentive to Dillard. Dillard acknowledged this and spoke of additional examples in other areas of their relationship.

Step 7: Introduce Outsider Witnesses to Consolidate Preferred Stories

The introduction of witnesses to these changes serves to further "thicken" preferred stories, providing further solidarity with partners and introducing information to further support the deviations. The therapist can ask

Of all the people you have known, who would be the least surprised to see you taking these steps?What would this person tell me if they were here and I asked them to tell me a story about how they came to believe in you in this way?

The therapist asked Genevieve about people such as close girlfriends and what they thought about how Dillard treated her. Dillard was asked a similar question. Both responded that their friends like their partners a lot. The therapist challenged them whether their friends would hold back criticism to be nice. They both laughed and said their friends had been quite candid… "brutal" was a better term when friends had judged the problematic people they had dated previously. Dillard told a story about his brother who told him shortly after Dillard and Genevieve started dating, that she was the one. His brother had told him that not only was Genevieve a great gal, but that he had never seen Dillard so stable and positive. Genevieve said that Dillard drove her an hour home for a family crisis- a four hour round trip, the second week after they had started dating. Her siblings had been impressed that he would do this for her. They said they knew from his willing to go out of his way to drive her that he shared Genevieve's values about family. None of her previous boyfriends probably would have done it… and definitely, not so early in the relationship.

Step 8: Collapse Time

Once small exceptions have been amplified in this way, it is important to return to the reality of the relationship's small changes, not as demonstrating that they have significantly progressed towards 'beating the problem' in the present, but rather as something that has the potential to gather momentum if the individual, partners, or family members commit to further change. One way of achieving this is to "collapse time," causing the individual, couple, or family to reflect on the significance of changes that could take place if they were to continue to interact in these ways. The therapist can ask

If I met you in three months and these developments had continued, what would you tell me could have happened regarding the problem you initially came to see us about?If I met you in three months' time and these developments had continued, what would you tell me about the relationships between you?If I met you again in three years, how significant would you tell me the changes you had made in these two weeks were? In the life of the identified client? In the life of your family?

The therapist asked Dillard how it would be for him if Genevieve continued improve for the next few months as she had recently. Would he have wanted to come to therapy if things were as they are now? Dillard commented that knowing that Genevieve cared made it so he could keep faith and hope that they would be ok. It was not really about her being on time, so the confidence itself was a big change. He could see it getting better and better. Genevieve could see they were on a good path and she felt confident they could make it. Before their recent changes, she was not so sure. They both felt much more secure and calm. It was a lot easier to let things go.

Step 9: Identify Progress and Stimulate Deviations with Scaling Questions

Scaling questions can also be employed to support the momentum of virtuous cycles, in particular between the second and third sessions (for brief or time limited therapy, the timing comes relatively soon in the sessions; for other orientations, it may be at a later as therapy comes to a conclusion). Future-oriented scaling questions can also serve as substitutes for the therapist's prescription of systemic tasks.

Imagine a scale of 1 to 10, where 1 is how things are in the family at their most difficult, and 10 is how you would like them to be. Where would you rate things at the moment?Imagine that when I see you in two weeks' time, you have progressed by half a point? What would you tell me had happened? What would you tell me had been involved in achieving this?

The therapist asked Dillard if he expected Genevieve to never forget to call again and never be late again. Dillard said he knew that mistakes happen and he just needed to know that she'd improve. Genevieve said she could do that but was not sure that Dillard could be satisfied… and that she would get blasted if she messed up. "How much better does Genevieve need to be? How much worse was she?" asked the therapist. "Is she allowed a mistake once a month… once every two months?" "Well, she used to do it all the time," said Dillard. After some discussion (arguing), Dillard and Genevieve agreed it was about once a week. "So, is once every other week twice as nice!?" queried the therapist. "That would be a start," said Dillard. Genevieve said she had not been late or forgotten to call for the last three weeks- or since therapy began. The therapist asked her, "What did that take?" She responded, "Well, knowing how upsetting it was to Dillard… at a deeper level than just him complaining. I kinda got that the first session. I made it a bigger priority. I didn't want him to feel I didn't care." The therapist asked, "What would it take to keep it up and continue improving?" Genevieve smiled, "Him being positive and appreciative… knowing he knows I'm trying, all that keeps me motivated and focused. It's gotten to be more a habit to call, rather than something I have to gear myself up to." Therapy may not go as easily as with this couple. The presenting issue with Genevieve and Dillard was relatively simple. Addressing it did not uncover intense resistance or highly emotionally reactive core issues that could not be managed. The therapist often finds that the concepts in a strategic approach remain relevant to more difficult clients' situations.