Conclusion & Postscript - RonaldMah

Ronald Mah, M.A., Ph.D.

Licensed Marriage & Family Therapist,

Consultant/Trainer/Author

Main menu:

Conclusion & Postscript

Therapist Resources > Therapy Books > How Dangerous

How Dangerous is this Person? Assessing Danger & Violence Potential Before Tragedy Strikes

CONCLUSION & POSTSCRIPT

CONCLUSION

Tamerlan and Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, Scott Roeder, Cho Seung-Hui, Eric Harris, Dylan Klebold, James E. Holmes, Anders Behring Breivik, Jared Lee Loughner, Lyle and Erik Mendendez, Brian Mitchell, Phillip Garrido, Chris Brown, Ross Mirkarimi, Judge William Adams, Jerry Sandusky, James Moss, Prosenjit Poddar, Jimmy Lee Dykes, Jermeller Steed and Cicely Reed- could their violence been predicted? Who may have been a sociopath- someone with antisocial personality disorder? Who was narcissistic or had narcissistic tendencies? Or, borderline or paranoid? Who was frustrated? Were there triggers or the violence opportunistic? How much did cultural models, roles, or values increase frustration, volatility, or aggression? To what degree did extremist versions of religiously based values cause, contribute, or intensify individual vulnerabilities? There has been speculation that Tamerlan Tsarnaev's "radicalization" and "turn to Islamic extremism" lead to the bombings (Peleschuk, 2013). Scott Roeder, one of several individuals who have killed an abortion doctor asserted the righteousness of his action and professed no regrets (NBCNews.com, 2013). For others, did bullying get out of hand? How intense was the arousal? Was there any empathy or remorse? Several of these individuals, for example Garrido, Moss, Brown, and Mirkarimi professed remorse, but how genuine was the remorse? Breivik’s violence was completely self-righteous and ego-syntonic. Like Roeder, he professed his entitlement- his right to kill. He was proud that he had killed. Had he gotten pleasure from being violent? Cho felt the same about his violence. Cho had a litany of resentments against prior abusers and projected them onto others, including stringers. Did the Mendendez brothers hold similar thoughts and feelings: self-righteousness, entitlement, and resentment about killing their parents?

Some people who knew perpetrators expressed surprise at the violence because they had not observed any indicators, pattern, or history of prior rage, aggression, or violence. A variety of friends, classmates, teachers, and other acquaintances experienced no prior indication of violent thoughts or tendencies in the younger of the two suspected Boston Marathon bombers, Dzhokhar Tsarnaev (Walshe, 2013). Other people were revealed to have prior actions- patterns of aggression and violence that predicted the subsequent violence. Or, perhaps they verbalized or posted inflammatory aggressive rhetoric online. How are the hateful accusations against America by the older of the two suspected Boston Marathon bombers Tamerlan Tsarnaev similar to, the same as, or differ from any number of rants found in social media and websites, including those of arguably respectable political, business, and religious figures? Some violent individuals claimed their anger, aggression, or violence was in and from a transitory mood uncharacteristic of their normal functioning. Some individuals, despite their disclaimers of violent tendencies and somehow falling into an unanticipated violent mood, showed previous characterological anger, resentment, lashing out, aggression, or violence. Some killers or abusers were isolates while others were social. Judge Adams suffered no punishment for beating his daughter aside from some public condemnation, along with some public approval. Others were punished. Some seem to care deeply that they were punished, but Cho, Harris, and Klebold accepted their own deaths as worth the violence inflicted upon others. Tamerlan Tsarnaev ran into Boston police fire (Gray, 2013), firing his own guns like the suicidal charge of an epic warrior. Was it his intention to go down in a blaze of self-righteous glory? The violence appears to boost their self-esteem, while others were distraught and self-condemning… or at least claimed to be devastated by their transgressions.

These individuals are well known to famous, infamous, or notorious public figures as a result of prior achievements, status, or roles. Some became known only because of their violence. The therapist, professional, and concerned person along with other community members may be interested in, titillated, angered, or sensationalized by their aggression or violence. However, most people hold no professional responsibility or role to anticipate, prevent, or prevent repetition of violence. With the individual in individual, couples, family, or group therapy however, the therapist bears legal, therapeutic, and moral responsibility. Other medical professionals have similar responsibilities. Law enforcement professionals hold important roles to protect the public. A potentially violent or habitually violent individual often does not- usually does not announce him or herself in therapy, at school or work, or the public in general as being a danger to others.

The therapist, professional, and concerned person rues the experience of hearing after the fact- subsequent to initial sessions or meetings after the termination of therapy or treatment or employment, the individual’s acts of inappropriate aggression, abuse, and violence that were no real surprise. While one may not always predict the violence, the reality of not being surprised that the individual became abusive or violent means that the person had some sense of the individual’s potential for violence. This discussion has sought to help the therapist, professional, and concerned person quantify and conceptualize tentative instincts to direct deeper assessment and diagnosis, improve therapy, treatment, or intervention to deal effectively to reduce violent tendencies, and take specific interventions to prevent violence. The overall discussion, identification of profiles or diagnoses, and noting specific criteria are intended to amplify clinical, other professional, and personal intuition to develop conceptual and theoretical clarity about violence potential. With that conceptual and theoretical clarity, the therapist, professional, or concerned person can be more assertive clinically, professionally, and personally. If indicated and as needed, be empowered to take the necessary legal steps to protect others and the individual (in the case of self-harm and suicide).

“How dangerous is this person?” The therapist, professional, or concerned person may not know definitively, but remains responsible to know and therefore do as much as necessary. Are these conceptualizations and guidance sufficient to identify and thus, to prevent all future violence? Of course and almost certainly not. However, any violent act that is blocked and any perpetrator who is stymied, prevents one more tragedy upon the soul of an individual, a community, and society. The theories presented in this book may stimulate more successful conceptualization to prevent violence, or at least contribute to further to the discussion to direct policy and intervention.

POSTSCRIPT:

This work is the product of an ongoing process that I, as the author have been actively engaged in for at least six years. Tragedy after tragedy… public violence that I learned of through the media, and the private violence endured by silent and unknown victims continued through my development of key ideas. I literally was on the last edits to upload the file of this book into e-book form on Monday April 15, 2013, when my television to the left of my computer began screaming about bombings at the Boston Marathon. Like many other people, I tried to contact and check the welfare of a loved one in Boston. I texted my daughter, who had gone to graduate school in Boston almost seven years ago and created a life, developed a career, and found a community of wonderful friends there. Almost immediately, she called back. She was in a car, coming back from New Hampshire from a day trip. I had forgotten… she had told me she was going. She knew less than me and asked me what I knew. I misinformed her based on my limited and insufficient knowledge gained from CNN- much like a soldier becomes confused in the “fog of war.” She called me later to tell me that her friends were all accounted for and were ok.

At a training on Thursday- a couple of days later on April 18 that I conducted for agency staff that worked with at-risk teenagers, I met a young pregnant woman who had gone to Boston to run the marathon. Her back had become too painful after fifteen miles and she had to drop out of the race. She told her story of finding out about the bombings while recuperating at her friends’ place. Without saying it out loud, I thought probably as did everyone else, she could have been one of the victims.

The next day Friday April 19, I found a message on my business answering machine. My daughter had called and left a message to tell me that she was okay. She did not want me to worry. I had not heard, but she was housebound with the rest of Boston and surrounding areas, as the authorities searched for the surviving bomb suspect Dzhokhar Tsarnaev. I continued my edits on this book while watching the CNN updates about the search around Watertown. With somewhat morbid curiosity, when CNN gave the address I went online to see a satellite photo of the house where the suspect hid in a boat in the backyard. When they announced the capture of the suspect, I with thousands of others felt a personal sense of relief.

I continued to follow the updates that came out sporadically the following week, partly from personal curiosity and partly from professional fascination and responsibility. And with a continuing sense of frustration, that “it” had happened again… and that “it” will happen again. Mention and description of specific individuals and events date this book. Unfortunately, assessing for the violence and danger potential of individuals remains timely and will remain timely. I considered delaying publication of this book to bring it up to date by incorporating findings about the Boston Marathon bombings. Based on the early bits of information available in the media, my instincts indicate that the bombers fit within the thesis presented here. However by the time, authorities and speculators develop relatively conclusive findings about the perpetrators and their motivations, there may be… and I am afraid that there will almost inevitably be other acts of violence by other persons shaking on our collective psyches.

As the original impetus for this book came from Virginia Tech in 2007, that tragedy became background for what happened at Aurora, Colorado and Shady Hook Elementary. And as those deaths and injuries foreshadowed the bombing at the Boston Marathon, the two pressure cooker bombs at the finish line during Patriot Day will become pre-history to other violence. So, too will further child abuse or domestic violence or workplace shooting be incidents in the ongoing chronicle of suffering of known family and friends unknown neighbors. A book such as this may never be up to date, but unfortunately it will remain timely for the foreseeable future. Maybe this book will help that “it” won’t happen as often, or to you, a loved one, a client, or to your community. Perhaps, aggression may be addressed before it becomes violence against another person, and violence be blocked or minimized before it intensifies and creates greater havoc. It is our personal and professional responsibility to create as safe and secure a world that we can. Thank you for reading this book. Thank you for caring. Thank your participation.

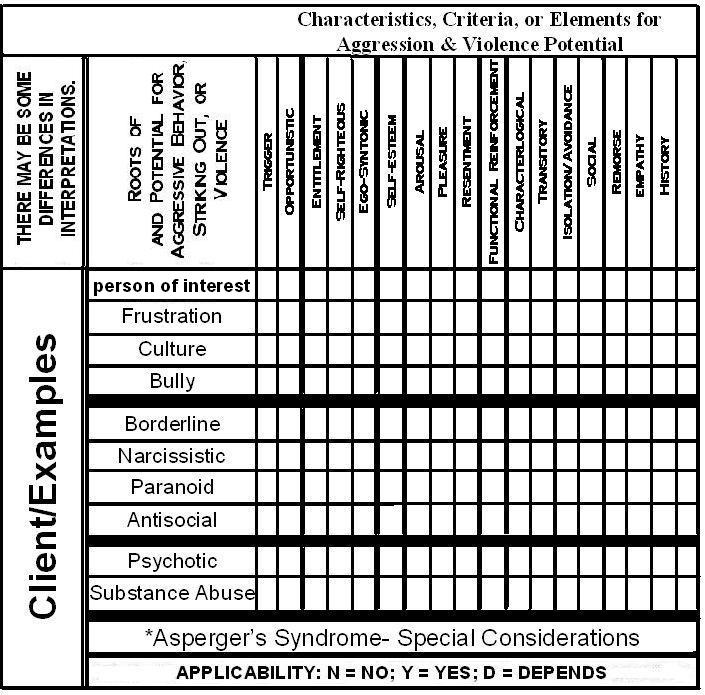

The chart: The therapist, professional, or concerned person can fill it out using his or her professional and/or personal knowledge and experiences to create his or her own conceptualization of the profiles or diagnoses.