10. Working Out Plan - RonaldMah

Ronald Mah, M.A., Ph.D.

Licensed Marriage & Family Therapist,

Consultant/Trainer/Author

Main menu:

10. Working Out Plan

Therapist Resources > Therapy Books > Mirror Mirror- Self-Esteem Relationships

Mirror Mirror… Reflections of Self-Esteem in Relationships and Therapy

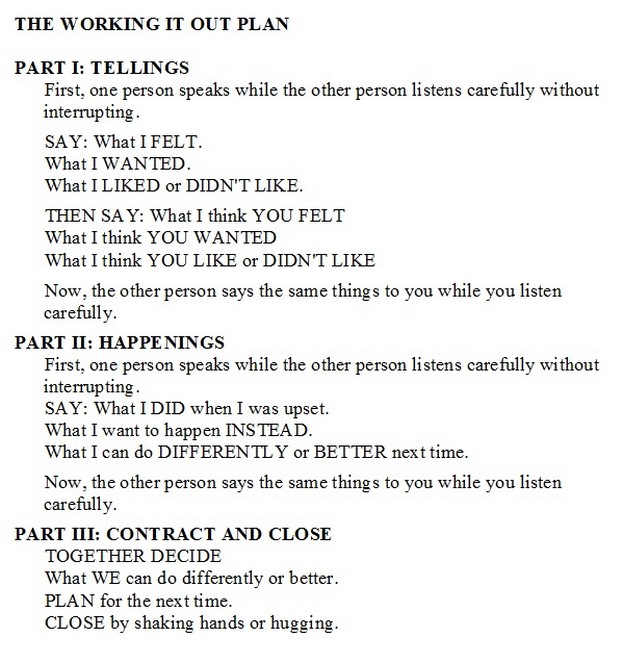

Chapter 10: THE WORKING IT OUT PLAN

by Ronald Mah

A pragmatic tool may be beneficial for individuals to create positive resolution. The "Working It Out Plan" attempts to create in a practical form an aid that will increase self-awareness, increase empathetic awareness, increase responsibility, and help to preclude future problems. This can be used as a guide for individuals in conflict to work things out. It can be presented to an individual to understand his or her process- perhaps, in preparation for working it out with the partner or family members, or to the relationship, couple, or family together. The first part of the plan, "TELLINGS" purposely focuses on feelings. The very first rule may be the most difficult one for partners.

First, one person speaks while the other person listens carefully without interrupting.

When one person- for example, Terry begins to speak, he or she will speak from his or her own perspective and experiences. This will almost inevitably include elements that the listener Bert finds irrelevant or insinuating, and exclude elements that the listener considers important or more specifically, damning. There is often a visceral reaction as the listener hears the speaker's egocentric rendition of what happened. The listener may "comment" with sighs, rolling his or her eyes, shaking his or her head, body shifts, and other non-verbal messages. Quivering with anxiety or outrage, the listener often feels compelled to interject "clarification" or the "truth." The listener acts as if his or her reality... his or her very existence is being distorted as the speaker's perspective differs from his or her perspective. The listener can completely disrupt any flow of information from the speaker by continually interrupting, disputing, correcting, adding, and "clarifying." If Bert does these things, they block Terry, the speaker's actual voice and his or her existential voice. The listener-interrupter, from fear of being annihilated or misrepresented effectively does to the speaker what he or she implicitly or overtly accuses the speaker of doing to him or her. The therapist has to enforce a very strong boundary that the listening person must remain silent. For Bert and others, the boundary includes that he or she may not express a plethora of negative non-verbal messages. The therapist should also emphasize that he or she listen to understand not just the factual or cognitive information, but to connect with the emotional message. "Bert, don't focus so much on the 'facts' of what Terry speaks of. Pay attention to how she is feeling about this." Contentious individuals will "listen" carefully so that he or she can dispute the speaker's rendition of the situation or experience. Disconnected "listeners" will shut down without taking in any information, that is remain silent and wait for their turn to speak. The therapist needs to confront either negative dynamic since in either case there is no real receptive communication.

When an individual is in conflict, he or she usually feels accused and becomes immediately defensive. Both Bert when Terry speaks first and then Terry when Bert speaks tend to anticipate being attacked and interpret any words or actions from this prejudice. This precludes the possibility of a positive resolution of an issue. Discussing feelings first, helps prevent a person from interrogating or being interrogated as to what one or the other did poorly. Interrogation usually creates immediate resistance. One individual should be allowed to express his or her thoughts and feelings to begin the process. This also allows the other person (the listener) an opportunity to explore empathy for the first individual (the speaker). As Terry in this example goes first, she is instructed to:

SAY: What I FELT.What I WANTED.What I LIKED or DIDN'T LIKE.

The therapist should direct the speaker to his or her feelings underlying his or her words. "You thought Bert was ignoring you. How does or did that feel, Terry?" This may be done as by reframing speaker statements. Or the therapist can emphasize feelings by asking about them directly. Individuals often need to be lead to how they feel. "Say 'I felt...', not 'he or she did...'" The therapist attempts to make clear that this is not an examination of the facts- only of his or her feelings. Facts are minimized (perhaps, for the time being) as not particularly relevant. By starting with feelings, the process offers validation to the speaker that he or she was bothered. What happened is less important than acknowledging that his or her sense of inequity or being harmed deserves consideration. This does not make it ok what he or she did in response, but it does validate that he or she was upset. Encouraging the speaker to say what he or she wanted validates that there was something that was desired. Sometimes asking this question overtly causes the individual to examine for him or herself more carefully what motivated him or her. This clarification may be beneficial for both or all individuals to find out what they are really fighting about. The other vital point of asking what was wanted is to remind the individual that no matter how righteous he or she may feel, the interaction had failed to gain what he or she wanted. Asking or having the speaker say what he or she liked or did not like acknowledges that there is a grievance that is real to him or her. The emphasis is that the experience of the hurt or distress from the grievance is existentially valid, whether others agree or disagree with any interpretation of events. The initial set of three questions or verbalizations encourages the individual to be introspective rather than accusatory. The individual's self-esteem is enhanced with the experience of being given a platform to give voice to personal feelings, wants, and likes.

THEN SAY: What I think YOU FELTWhat I think YOU WANTEDWhat I think YOU LIKE or DIDN'T LIKE

A person's greatest urgency is often to be able to express his or her experience. His or her greatest fear may be that he or she will not be able to express it or be heard. Once an individual is able to speak (without interruption), his or her level of anxiety often diminishes. Having been given the forum to say what she felt, wanted, and liked or did not like, allows Terry to calm somewhat. When prompted next to guess what was going on in the other person, the lowered anxiety may help the speaker be more objective. This is an attempt to mirror the other person, although it is usually charged with assumptions. With her existential or emotional self already having been heard, Terry is hopefully less compelled to make a case against Bert with over-the-top judgments. And may have freed her to really consider Bert's experiences. Prompting the individual to say what he or she thought the other person felt, wanted, and liked or disliked is an attempt to foster empathy and understanding. It may be the early step to acceptance of the other person's experience. Regardless of whether the speaker is completely correct, partially correct, to completely incorrect, his or her perception will be revealing for understanding his or her emotional and mental process. If the speaker's perception of the other person's feelings, wants, and likes are incorrect, the process allows for them to be clarified. He or she is acknowledged as the owner of personal feelings and thoughts, but not the authority about the other person. Terry gets to own her feelings and experiences, but she only gets to guess at what is happening or has happened with Bert. The speaker is guessing about the other partner's feelings and thoughts.

Now, the other person says the same things to you while you listen carefully.

The second person- in this example, Bert now gets to speak his or her feelings, wants, and likes or dislikes as his or her own expert. In speaking, he or she gets to have the same experiences of validation as the first speaker. In revealing his or her process, he or she clarifies any misconceptions already verbalized by the first speaker. Bert might say, "I was not ignoring you. I was preoccupied… stressing about having time to pick up the uniforms before the shop closed. I was rushing." The accuracy of the first individual Terry to guess- that is, mirror is revealed. The therapist can make explicit that the quid pro quo of being accepted as the acknowledged expert on one's personal feelings and thoughts is that one then defers to the other person as the expert on his or her personal feelings and thoughts. Bert gets a turn to attempt a guess or mirror Terry's motivations- an attempt that will probably be inaccurate. The therapist encourages the two persons' reciprocal attentiveness to the other's personal experience. This may not have been possible if the therapist had not enforced the two to "take turns." With both having spoken, the basic foundation of the communication and of conflict resolution have been set. The foundation is not based on getting out or establishing the facts. The facts do not count! Or, more accurately the facts do not count as much as the feelings, wants, and likes and dislikes of each individual. Trying to get to the facts is a route that is inevitably corrupted by perceptions, bias, and old grievances if the individuals were allowed to argue unfettered by the therapist. They may be able to engage in this process on their own eventually, but most probably need the guidance and boundaries of the therapist initially. As the process is effective in therapy, the individual, couple, or family may gain the experience and confidence to practice it effectively at home.

The next part of the process is built on the individuals' reduced anxiety having been able to get out their feelings, wants, and likes or dislikes. When an individual experiences his or her experience being heard and especially, validated, he or she often becomes more willing to take responsibility for his or her actions or choices. The initial rule and process of taking turns remains the same in the "HAPPENINGS" part.

First, one person speaks while the other person listens carefully without interrupting.

SAY: What I DID when I was upset.What I want to happen INSTEAD.What I can do DIFFERENTLY or BETTER next time.

Now, the other person says the same things to you while you listen carefully.

The pivotal question occurs when the speaker is asked what he or she did when he or she was upset. The therapist may prompt, "So when you were upset about being ignored Terry, what did you do?" This advances the process from acknowledgement of his or her grievance, feelings, etc. and moves to the individual taking responsibility. This revelation does not question the individual's justification or explanation of regarding his or her behavior. Terry felt what she felt AND Terry did what she did. The process only asks the individual to state what he or she chose to do when he or she was upset. It acknowledges that he or she was upset, implying that he or she has a right to be upset. Validated once again and without a need to justify behavior, behavior can be more readily owned. There will be some individuals who will still be unable to take responsibility for his or her behavior. Difficulty taking responsibility implies that the other person holds power and control over the speaker's feelings and experience. The speaker implies that he or she does not control his or her own behavior- that is, the other person "makes" or forces the speaker's choices. This cannot be left unchallenged. Terry chooses her words and actions. Bert does not pull them out of her. And Bert select his communication and behavior. Terry does not control his choices. Taking responsibility can be challenging for someone who feels admitting a bad choice or acknowledging that the other person has been negatively affected is tantamount to a confession of wrongdoing. He or she may be resistant. What the individual may be actually resisting is a perceived request for him or her to blame him or herself. The individual does not yet understand that responsibility is not meant to be negative- and is not equivalent to blame. Instead of being frustrated at the individual's difficulty in answering these questions, the therapist should help him or her own how he or she affected the other person. This may involve exploring his or her values and experience of blame versus responsibility. Strong resistance taking responsibility would be indicative of a deeper rigidity and a more profound insecurity and/or the presence of highly sensitive emotional wounds.

Focusing the speaker to say what he or she wanted to happen instead validates his or her desires again. It also reminds him or her that despite possibly being self-righteous about everything, he or she did not gain what he or she wanted. Terry and Bert have failed frequently at getting what they desired. The therapist should frequently challenge a self-righteous or rigid individual, "So, how is that working for you?" Or, be more declarative by stating, "This is not working for you." The morality of functionality or practicality is asserted over some other ineffective morality. Prompting the individual to speak to what he or she could do differently asserts that there are alternative choices. An individual might complain that he or she "has" to act in a certain way, as opposed to choosing to. Even if he or she asserts this in a loud and aggressive voice and manner, the therapist can still reveal the stance as a victim stance. In a calmer place because of the validating process, the individual may be able to think of and propose more positive alternatives to his or her previous choices. One individual's ability to take responsibility, talk about what he or she actually wanted, and what he or she could have done differently often has a positive impact on the other person. It can often free the other person from his or her resistance and defensiveness when he or she takes his or her turn to speak. The other person is more likely to be accepting and compassionate. Most importantly, it may enable the other person to also take responsibility. The therapist works to get anyone to "go first." However, some individuals may still be unable to take responsibility- to follow up by taking a turn in response even though the other person has already owned his or her part. The therapist should recognize that deeper complexities occasionally to frequently preclude otherwise effective conflict resolutions processes from working. It may be indicative of extreme emotional frailty and very low self-esteem.

The final part of the process, "CONTRACT AND CLOSE" looks beyond the current or latest conflict to future interactions and the overall quality of the relationship. The process is not only for dealing with the current situation, but to also to educate and prepare the partners to collaborate successfully in the future.

TOGETHER DECIDE

What WE can do differently or better.PLAN for the next time.CLOSE by shaking hands or hugging.

The therapist has the individuals discuss what individually and collectively they can do differently or better. "Terry, what can you do differently? Bert, what can you do differently? What can you do differently together next time?" Although each individual has already said what he or she can do differently, a collaborative process is essential. The repetition of discussing how to do things differently is entirely purposeful. Doing it the same way is a dead end- a dead end that has brought the individual, couple, or family to therapy. Either Terry or Bert may be prompted to speculate, "Maybe, if either of us doesn't like something, we can agree to check out what the other person intends," or "How about if we start to get negative with each other, either one of us can say, 'Let's talk about this in therapy, before we make any decisions?" Getting either individual to propose collective actions to agree upon is a significant shift in their dynamics. Of course, there is not a guarantee that what the individuals do individually or together will be effective. However, doing something different offers the opportunity for something better to work out. It breaks the cycle of repeated ineffective interactions. Having the individuals' plan for the next time asserts two important principles. First, there will be a next time- probably several next times when they will have miscommunication or conflict. It is a dangerous illusion to believe that good intentions and a couple of positive therapist facilitated resolutions of conflict will readily ignite permanent change. Terry and Bert need to know that this is a process that requires ongoing vigilance and work. This prompts the individual, couple, or family to be vigilant about continuing to work on their skills and process. Second, since there inevitably will be other future conflicts, planning or hoping that there will not be conflicts or that they will magically become easy to handle is naïve. Discussing and agreeing to a plan to deal with misunderstanding and upset allows any individual to activate some alternate process than the negative process they have been following prior to therapy. Included in a plan should be permissions given to one another to intervene, interject, or interrupt negative processes. Permission empowers the individuals to say and do things in the heat of conflict that may otherwise have been too dangerous or provocative previously. Rather than antagonizing the other, agreed permitted words or actions would be seen as helping the process. Discussing a plan can simultaneously deepen the individual, couple, or family's understanding of, increase their investment in, and raise their confidence in their process.

The last element of the process is to close by shaking hands or hugging. These behaviors or other rituals signify a contractual agreement between two invested and benefited individuals. The therapist can be playful and point out that some couples when reaching a positive resolution to a conflict will do more physically than merely shake hands or hug. In fact, there is a name for this closing ritual- makeup sex! Obviously, not appropriate for Terry and Bert as an already divorced couple, but a handshake may be sufficient. Regardless of the style, physical contact is both symbolic of the individuals' emotional reconnection and powerful functional communication. Physical touch during the conflict resolution process may in of itself, turn it into a calmer problem-solving conversation. Avoidance of touch is both a consequence of disconnection and precipitates disconnection. If the therapist can get the couple or family to gently touch (holding hands, sitting together with arms around shoulders for example) at any point during the process, their mood shifts and becomes conducive to connection and resolution. The mediator starts two antagonists to shake hands in a comparable manner. The therapist can require the partners in a couple to sit touching or holding hands if they get into an argument. While this instruction may be difficult to follow as an argument rapidly ignites, the principle can be applicable otherwise. The couple can be instructed that either partner prior to initiating a potentially difficult discussion to first hold the other partner's hand or sit along aside one another so that they touch. With the positive resolution of conflict, a hug or other intimate touch is not just a natural conclusion, but also provides sensory confirmation of reconnection. The touch will feel "real" if the resolution is sincere. As noted, a handshake can be an important beginning but also closing ritual signifying resolution and respect. The following is the plan or process in outline form. It is suitable to be given to the partners as a guide for home use.