Incentive Beh Mod Prog - RonaldMah

Ronald Mah, M.A., Ph.D.

Licensed Marriage & Family Therapist,

Consultant/Trainer/Author

Main menu:

Incentive Beh Mod Prog

for Parents & Educators > Articles > Other Articles

Incentive Based Behavioral Modification Program

Maybe if I give her something, she'll behave better. But if I give her something to do her work, then maybe she won't do anything anymore unless I keep on giving her something. But she's not behaving now, so what's to lose? My dad doesn't think you should get rewarded for something you're supposed to do anyway. When I got straight A's, I didn't get anything for them. I was expected to get straight A's. In fact, when I got a B that time, I got yelled at. Maybe if I put her on timeout, she'll behave better. But when I do that, she gets even angrier and fights with me even more. She doesn't seem to care how many privileges I take away. She just gives me that dirty look and goes hides her face on the desk. And, there's no way I can get her a toy like some teachers or parents do when she gets good grades. Shoot... I'd be happy if she just tried! She wants a more free... maybe I can give her some free time right before lunch. She promised that she would “be good” if I let her play. But once she gets what she wants, she probably won't behave or try anyway. "I'll gladly pay you Thursday for a hamburger today." Isn't that what Wimpy used to tell Popeye all the time? What am I to do?

There will be times when a more formal and organized reward system can be useful with the child and classroom or family. Many times, either parents or teachers respond to the possibility of an incentive program in helping motivate children with, "A reward system? We've tried that and it doesn't work." Well, they didn't do it correctly! People often have tried reward programs and had very poor results from them. Yet, among the most basic principles about human behavior is that when people are motivated by potential rewards, they are much more likely to change their behavior. Pavlov and his famous dog that salivated at the ring of a bell are well known to many people. Maybe we are not Pavlov and our children are not dogs! However, positive and negative reinforcement, conditioned response, unconditioned response, and reward and punishments are all concepts that whether or not we are conscious of them, are constantly used in our relationships. Even if you do not use a formal behavior incentive plan, if you have successful relationships with children, you almost certainly use an informal intuitive casual behavior incentive plan! And as you read about the principles and practicalities of an effective and successful formal behavior incentive, you will almost certainly find that your informal intuitive casual interactions and relationships with children follow the same principles.

Unfortunately, what most people call a reward system often ends up being a punishment system. Or, this may be from people who have been unsuccessful with what they thought was a reward system. Instead of motivating children to behave more appropriately, a poorly designed reward system that focuses on punishment ends up causing them to be unmotivated. Ironically, the suggestion of a behavior incentive plan-or reward plan is often not seen as something different, but what has been tried and has failed previously. Looking at what an incentive plan should be about may help people understand that this kind of approach is different. Or, you can look at these principles and practicalities about a behavior incentive plan and see just how good or skilled you have been all along!

KEY ISSUES & THE DILEMMA

Many people in general are seeking greater control in their own lives as a means of dealing with the lack of power and control they otherwise feel in their own families, school, and the community. As a teacher or a parent you are reading this book to get more knowledge, insight, perspective, and tools to help you get greater power and control of your management of the children you are responsible to teach and nurture. Children who become oppositional often want greater power and control in their lives. Anything that allows them (or us) to have greater power and control or a sense of greater power of and control in their lives (for us, such as being effective teachers or parents!) is highly motivating. The issue for adults is to instill the discipline that they exercise power and control in appropriate ways that are not violating of other people's rights. In addition, many oppositional behaviors are attempts to get validation (not just attention) from adults. Validating experiences confirm to the individual that they have value as human beings. The parents and family of oppositional children, for various reasons, are often ineffective at giving appropriate validation and attention. A teacher and his or her classroom may be similarly ineffective. They may lack sufficient skills at nurturing a sense of worth of their children. Or, they may be so overwhelmed with stress dealing with the demands of their lives, that they barely keep their own heads above water and can only marginal support to the children. Such adults usually feel out of control themselves (and not just with their oppositional children). The new mandate from the school district… the new guidelines for curriculum… the extra meetings… standards… testing… “Lions and tigers and standards, oh my!!” Obviously, there's nothing to highlight your own sense of being out of control more than not being able to control your own classroom or family of snotty kids! In addition, if you feel out of control about your finances, your job situation, your prospects, your weight, and so forth, you're dang sure a whole less likely to put up with any guff from your kids! As a result, not surprisingly oppositional children and their parents or teachers often end up in a power struggle where both lose. Punishment usually has become the mode of discipline despite its ineffectiveness. Quite often, punishment was the main, if not the only form of discipline that many adults experienced from their own parents when they were children. Interestingly, many adults will admit that punishment was not effective to motivate them to behave as children either! And, many teachers and parents will also admit that punishment is not working to motivate their children right now in the classrooms and home.

Many behavioral incentive plans include both rewards and punishments. Life is about both rewards and punishments. Many classrooms and families have effective behavioral incentive plans that include both rewards and punishments. If you already have such a plan-an effective plan that works, then you should maintain it or perhaps only tweak it to improve it (but if you had an effective plan, you wouldn't need this book!).

Principles of an Effective Plan

Whenever someone presents a technique or a process -- a magical solution to all the problems, they sometimes forget to address the underlying principles for the technique or process. They may address only the goals. It is important to articulate the principles and to tie them to the specific goals. An effective reward system will seek to:

1. Create real (and appropriate) power and control for both children and teachers or parents.2. Create means for the child to get validation.3. Defuse the power struggle and create the "Win, Win" situation.4. Remove punishment as a mode of discipline and replace with reinforcement/reward principles.5. Remove conflict from the relationship and replace with contracts.6. Remove anger as relevant to the relationship.

1. Creating Real Power and Control

Power and control that is relevant to an adult may not be relevant to a child. As adults (hopefully), we tend to think of more future oriented rewards and consequences than a child who thinks and experiences only in the present. While scoring highly in a standardized test is relevant and confirms to a teacher the child’s aptitude in some way, and may have tangible consequences including status, financial rewards, and power or control for the teacher, higher scores are not relevant as real power and control for the child. What matters to the child? Sometimes, all you need to do is ask them what is important to them. Later on in the section on Goals and Rewards, a father demonstrated that failure to ask. Power and control with children often has to do with having choice. The limits of choice should be determined by adults. The teacher for example, gives the choices of more free time, a new bookmark, a little toy, more computer time, extra recess, extra arts and crafts or music—all of which are acceptable for the teacher to grant and all choices the child may be interested in.

Choice has to be real choice. Sometimes adults present “choices” that are not real. Sometimes, the choices haven’t adequately framed and the child makes a choice that hasn’t been anticipated or is reasonable but not the one the adult prefers. Then the adult will say, “Are you sure you want that?” That question is deceptive because it really isn’t even a question. It really is a declarative statement, “That is not the choice I want you to make! Chose again. Make the right choice this time!” If the adult is trying to coerce, “guide,” intimate, or even intimidate the child into making the right choice, then that is not real choice, and the child is not experiencing real power and control. You need to present great choices, good choices, mediocre, and mildly blah choices and be ready to accept them for a child to experience power and control. A child “guided” or forced to a great (in the adult’s perspective) will not ordinarily experience satisfaction. He or she will learn that his or her judgment is not to be trusted. Let them make their mistakes.

2. Create Opportunities for the Child to get Validation

When a child is considered for a behavioral incentive plan, the relationship and process between the child and the adult has probably already deteriorated to the point that the feedback the child normally gets is invalidation. The behavior of the child has often become so problematic and the frustration of the adult has become so severe that there probably is a significant deficit of validation over a long period. In fact, the adult sensitivity and vigilance has risen so that usually he or she expects the child to misbehave and tends miss naturally occurring positive behaviors altogether. And/or, conversely the child has come to expect to be scolded and tends to miss positive reinforcement or validation from the adult. A cycle of negativity often has been established between the adult and the child, and in the classroom situation between the child and the other children. One of the implicit goals of a behavioral incentive plan is to break this negative dynamic and give the child specific concrete opportunities to get validation and to re-train or re-stimulate the adult to give validation for structured specific behaviors. In some cases, it is the adult

who has forgotten how to be positive—become out of practice so to speak at nurturing this child. The plan becomes a behavioral change plan for the adult as well! The plan will not work if the adult fails to identify the positive behavior to give due credit to the child. The adult’s acknowledgement (which is critical) of the behavior is in of itself validating to the child. Most if not all previous recent acknowledgements have been for negative behavior. On top of the acknowledge, “I see you put the toys away before the recess bell,” it doesn’t even take an additional breath to add, “Good job!”

3. Defusing the Power Struggle and Creating a “Win Win” Situation

When the adult is engaged in trying to make the child adhere to appropriate behavior or behave correctly, he or she often gets into a power struggle with the child. The child feels constrained continually to stop doing what is interesting or compelling for him or her and feels a lack of power and control. Since the adult is the one who constrains, a power struggle against the adult naturally arises for the child as well. With a behavioral incentive plan the child does not have to do the desired behavior (the focus of this type of behavioral incentive plan is initially not on eliminating negative behavior but on increasing positive behavior). It’s great if he or she does do more positive behaviors, However, on the other hand, it’s just too bad… disappointing… unfortunate… regrettable that he or she isn’t doing the positive behavior or doing it frequently or consistently. It is not required or demanded (a power move on the part of the adult) that he do the positive behavior. However, it is recommended! And desirable! And rewarded! In addition, if the child does not do the positive behavior, it is an omission versus a defiance (a power move against the adult). And no one has to be angry… too bad, so sad, not glad, not mad!

No one loses per se because there is no power struggle anymore. The child either doesn’t do any positive behaviors at all (normally, unlikely) and then does not get any rewards, or does them occasionally or slowly and slowly earns rewards, or does them frequently and consistently and quickly earns rewards. There is a Win Win for both the adult and the child just because they don’t have to have a power struggle anymore. The adult wins because he or she gets disengaged from a (losing!) power struggle, is guided to be positive, and still promotes positive behavior (doesn’t give up). The child wins because he or she gets disengaged from a self-destructive power struggle (he or she loses no matter what the outcome), have positive behavior encouraged, and gets rewards for the positive behavior.

4. Remove punishment and replaces it with reinforcement/reward principles

Punishment is often over used even though it is clearly ineffective and inappropriate. Punishment is a form of negative reinforcement but not the only form. In addition, it is not the same as reinforcement. Discipline when focused solely on punishment becomes entirely negative—about what not to do and about “or else!” rather that what it is supposed to be in a positive outlook on life (discipline is about creating disciples that live a healthy productive life). Punishment and negative reinforcement can be the foundation to discipline and has been for many thousands of generations of children and adults. However, fear, oppression, domination, and exploitation also have been the foundation to societies, classrooms, and families for generations as well. In a more civilized society and in a more evolved civilized classroom, positive motivations and positive reinforcement teaches a principle and philosophy of positive energy and progressive living more reflective of modern democratic society. Adults get to disconnect from finding ways to scare or intimidate children and search instead to activate the positive motivations in children. Children live and work

not in fear and anticipation of being humiliated, hurt, deprived, or emotionally or physically abandoned, but instead strive to find self, other, and community rewarding behaviors. Addition of positive rather than deletion of negative is promoted. The energy of the classroom, of playgrounds, of relationships, and of families is shifted towards the positive from the negative. Remember also that the elimination of negative does not in itself ensure the production of positive.

5. Remove conflict from the relationship and replace with contracts

Conflicts arise between a child and an adult when there is an expectation for the child to behave a certain way, which the child fails to perform, and when the adult attempts to force the child to that behavior (or to eliminate that behavior) and/or is angry at the child. The child will be openly or passively defiant in the conflict, resisting the demand for the behavior and reactive to the anger directed at him or her. "You can't make me!" in an angry tone verbally or in nonverbal messages is the response of the child. "You better do it!" is the demand of the adult. The conflict is on.

On the part of the adult, there is an expectation of performance based on an explicit or implicit contract between him or herself and the child. Unfortunately, implicit contracts are often more the case than explicit contracts. Or, explicit contracts that have been verbally expressed are compromised by the lack of consistency and follow through by the adult. The lack of consistency and follow through (the critical nonverbal communication which is perceived as the truth) voids the contract. Only when expectations are clearly expressed by the adult and are overtly accepted by the child is there a contract. If you hear yourself saying, "You know what I mean," you may not have been explicit enough for the child. Many times, adults get caught in this situation because they are themselves not clear and/or have not actually anticipated what they desire in terms of behavior until the negative behavior has expressed itself. Figure out what you want and put it in terms of a contract.

"If or when you __________, then this ____________ will happen.""If you want ____________, you need to do _____________."

Make the reverse terms of the contract explicit. Putting out the positive terms of the contract does not address the negative terms of the contract. Being told what to do in order to get something, for many children does not equate being told what happens when they don't do what is required. For many children, their experience is that they are told, "If you eat your vegetables, you will get ice cream for dessert." They eat their vegetables and they get ice cream for dessert. However, some of them don't eat their vegetables or don't eat all of their vegetables, and the implied consequence of not getting ice cream for dessert turns out not to be true! Bighearted (also known as wimpy) parents or adults give them ice cream anyway.

"If or when you don’t __________, then this ____________ won't happen.""Although you wanted ____________, since you felt you didn't need to do _____________, you won't get ____________."

If the adult is clear that the contract has both the positives and the negative outcomes and is able to remove him or herself from needing to make the child take the positive choices -- perform the positive behaviors, then the need or the tendency to get into conflict is removed. The adult can encourage and direct the child to the better choice, but not need to make the child take the better

choice. The sense of intimidation or manipulation that the child would otherwise experience is removed. If the child makes the better choice (the positive behavior), the adult can be excited and supportive of that choice. On the other hand, if the child makes the poor choice (either the absence of the positive behavior or negative behavior), the adult can be disappointed in the choice and disappointed that the child does not get the reward of the contractual agreement, but does not have to be angry at the child. The adult can empathize with the child's disappointment without getting caught up in the child's anger. The adult can reinforce to the child that he or she did make a poor choice and that the negative consequence is disappointing. And, can encourage the child to make a different or better choice next time.

6. Remove anger as relevant to the relationship

Either the anger of the child or the anger of the adult (or both individuals’ anger) ignite each other in the conflict. When the child is angry, he or she has difficulty taking responsibility for his or her choice and has difficulty learning from the lesson of poor choices. A poor choice is a great lesson if it is pondered and considered. On the other side, when the adult gets angry he or she normally is unable to empathize with the child. Anger at its close relative, resentment (that the child has made a poor choice... that the adult couldn't make the child make a good choice, and so forth) disconnects the adult from the child's emotional distress at being disappointed. By being empathetic, the lesson the adult can teach about good choices can be nurturing as opposed to being a vindictive, "I told you so!" In addition as discussed elsewhere, the child's attention is drawn to the anger because it can be intimidating and distracted from the behavior or the lesson that is supposed to be learned. The adult’s issues with having a child be angry at him or her also gets ignited and is distracting from the teaching he or she is supposed to be doing.

A Reward-Only Behavior Plan

In many cases, classrooms or families cannot institute an effective behavioral incentive plan with both rewards and punishments, because they have already taught their children to be immune to punishments, or too many children come to your classroom from families where they have developed the immunity to punishment. In addition, some adults have intensified their punishments to a degree where they have become unfair and hurtful, and/or become highly inconsistent with their administration of punishments and the degree of punishment. In such situations, the behavioral incentive plan must be a reward-only behavioral plan. Strongly consider this for your classroom.

Even though you may be a fairly positive person, remember that the children come from very mixed experiences and it is likely that some have had very negative experiences with punishments already. Therefore, try starting out with a reward system with absolutely no punishments. Absolutely no penalizing children by removing already earned rewards- or making up new punishments. Removing already gained rewards or "points" serve to discourage children from trying. In addition, usually the removal of rewards or points (which is symbolically, if not also functionally, the same as a punishment) occurs when the adult is angry or frustrated about something. The adult removes the rewards or points in response to an unexpected transgression not discussed or included the behavioral incentive plan.

Do not ever take away points

Some house sold or classrooms (especially, group home programs) use a reward system to motivate children towards positive behavior. Over the days in the weeks, a child can earn hundreds of points doing simple chores such as making their bed, putting away dishes, doing homework, and so forth. By reaching a certain number of points as a goal (say, 1000 points) the child earns a special privilege such as being able to go to a theme park. Like the other children, the child finds such a privilege very attractive and highly motivating, and thus works hard at it over the weeks. Unfortunately, the same child in a moment of frustration or anger might do something (such as curse at or it into a fight with another child) and an angry adult will punish the child by taking away several hundred points.

In an instant, everything the child has earned and has been working at for weeks disappears. All the positive behaviors suddenly count for nothing. One mistake erases all the effort. He or she learns that the world is arbitrary and unfair -- that a devious adult has seduced him or her into a process and then betrayed him or her later on. What's the point? Why bother working at all these points, if it's all going to be snatched away from you anyway? Basically, the children learn, "The heck with it! I'm not trying anymore!" This is one of the primary ways that adults sabotage a behavioral incentive plan -- in other words that how they "did it wrong (incorrectly)!" The instinct to punish is often so strong in adults, that they sabotage incentive programs that would otherwise work. It is normally in the midst of frustration and/or surprise that the adult is reactive and will suddenly take away all credit and acknowledgment of previous positive behavior. "You don't deserve it anymore!" Even in the adult world, if you really screw up at work and they fire you, you are entitled to payment for the hours that you had worked up until being fired! It's not, "Never mind, you don't deserve it anymore!"

In frustration, a teacher sabotages a good plan

A behavioral incentive plan in the classroom may focus on the morning routines necessary to facilitate the classroom activities. Such a plan may be completely applicable to a child in your classroom who has issues organizing him or herself to transition into other activities. Each element (sitting at the desk by a certain time, putting away art material, washing up, getting work material, and being prepared to leave- backpack, lunchbox, etc.) successfully executed gains the child one or more points that he/she accumulates which can be exchanged for some predetermined rewards (extra computer time, a treat, free playtime, stickers, and so forth).

Leslie had such a plan. The child had been successfully following through and earning points throughout the week. He was excited and looking forward to "cashing in" his points for time to play a video game on the classroom computer. Late in the week, Leslie got into a fight with another kid. The teacher, upset at Leslie wiped all of his points off the ledger. Despite doing exactly what they had agreed upon (the morning routine issues), the boy was denied his reward. Leslie's response was basically, "Forget it! I quit! There's no point in even trying. Teacher will make up some other excuse and I won't get any reward... ever!" Behavior incentive plans work for the most part. However, the instinct to punish is so strong, that adults will often sabotage them. The teacher sabotaged the process. As the all-powerful teacher in classroom, it would be very easy for you in a moment of frustration to sabotage the process as well by introducing some new arbitrary reason for punishing or removing some or all the points.

Make the Plan Practical

A behavioral incentive plan has to be specific. It cannot be a "be a perfect child" plan. It cannot be an "anything else that I might not like" plan. It cannot be an all-inclusive plan. Such a plan is the beginning step in an overall plan and process to turn the child's behavior in the right direction. It's important to remember that the child's behavior did not get negative suddenly in a moment or two... or in a day or two... or even in a week or month or two. Negative behavior that is resistant to the normal discipline processes of clear expectations and simple consequences including the pleasure or displeasure of the adult for the behavior has always developed over a more extended period of time. It started with simple things that were overlooked by uninformed or overstressed adults. It is impractical to think and hope that the behavioral incentive plan -- no matter how well designed it is will turn everything around. Start simple, make it work, and then you can build from it.

Focus on one aspect of behavior at a time

It is critical that it be a practical plan that focuses on a particular relatively confined and concrete area of classroom behavior or of life. Being or becoming a "good boy" or "good girl" is too broad and not concrete enough. Keeping your desk clean is specific and concrete. Playing nicely with other children is too general and broad. Putting your things away when you come in is specific. Been respectful is too general and broad (and totally worthy of attention, but too behaviorally vague for many children to understand. Don't worry, respect does come out of this process too). Once one particular area has been stabilized-the behavior has evolved to a more tolerable or acceptable level, then another area can be focused on or perhaps the first area can be expanded. Some people are not satisfied with this approach, since it appears to be working on areas that are too insignificant. They want bigger change in more substantial areas. However, more substantial change may be unrealistic and serves to set up everyone for failure by asking for too much too soon. My experience with simpler and less dramatic approaches is that both the child and the teacher or parent cannot be successful with a more complex approach if they have reached the point that they are even considering a formal behavioral incentive plan. Both the children and often, the adult have too much negative energy, too many bad habits, and too little skills at that point.

It is important to remember that casual behavior incentive plans that work are basically the normal positive validation and support and guidance of normal discipline between adults and children. When the casual and intuitive behavior incentive plans have worked, children will respond to the normal adult expectations of the classroom and family. If you are reading this section about behavior incentive plans carefully, you are looking at children for whom the casual and intuitive behavior incentive plans have not worked! Breaking it back down to the simple things create the foundation for the more complex behaviors later on.

Success in one area of behavior transfers to other areas

There is a fascinating transfer when there is success in a "simple" behavioral plan into other areas of the child's behavior. Having an area of success often breaks the relentless cycle of negativity and failure that had come to define the adult-child relationship. All six of the principles discussed earlier are activated:

1. power and control is created for both children and teachers or parents.2. A means is created for the child to get validation.3. The power struggle has been defused and a "Win, Win" situation has been created.4. Punishment has been removed and been replaced with reinforcement/reward principles.5. Conflict is moved and replaced with contracts.6. Everyone is happier and not angry.

Everyone feels much better about him or herself. On several occasions, the positive energy and sense of accomplishment motivated the child to improve in attitude and respect- in areas that had not addressed specifically in the behavioral plan. One child had been having problems using the restroom at school without getting very distracted and taking too long. Once, he became successful be motivated by a behavioral incentive plan to use the restroom appropriately in a timely fashion without taking too long or making a mess, he felt quite proud of himself and the teacher was able to use that as a springboard to making other adjustments in his behavior. Another child who has become successful in keeping her desk neat begins to transfer a positive attitude in doing neat work. These are small successes, but remember many of these children have had no successes whatsoever over an extended period of time. And, many of these teachers or parents have had little or no successes with these particular children over an extended period of time as well. With these small successes, adults as well as children see hope and investment rewarded and are more likely to reinvest hope and energy as a result.

Goals and Rewards

Selecting appropriate goals and motivating rewards. A critical step to making the plan practical is to carefully select appropriate goals and the subsequent rewards. Goals need to be age-appropriate and relevant to the situation. Goals cannot or should not be too far-fetched. The goal of getting into a good college is not an appropriate goal for a kindergartner! Rewards cannot and should also not be too elaborate or far-fetched. A contribution to the child's college fund is not motivating for a second-grader!

Define GOALS and REWARDS as different but related. Goals are defined by teachers or parents as behaviors that are productive in short-term and also in the long run. The short-term goals may serve to increase the functionality of the classroom or household routines and reduce conflict and increase cooperation (less hassle and less fights!). The longer-term goals are developing attitudes, values, and behaviors that will have positive consequences in the child's personality and life. If children defined the goals, they tend to be focused on very short term issues -- often primarily about not getting into trouble or about getting something they want right now. It is up to adults to take the lead and assert the value of goals that have a more enduring positive benefit for children. In that sense, these goals reflect values and morality of the culture the children will be a part of for the rest of their lives. These goals need to reflect the expectations and standards of society for its citizens.

Putting your toys away serves current functional needs (organization, being able to find them later, so others won't trip over them, and so forth), but also is related to and representative of being responsible to self and others. Quietly going to use the restroom and using it in a sanitary and responsible way also serves current functional needs, but is also related to being respectful of others’ needs for quiet and order and being responsible for one's environment. Drilling young children on these more global and more mature behaviors and responsibilities may get nods and agreement from them, but often not any real learning or integration of the principles and subsequent actual appropriate action by the children. However, the simple behavioral goals as they are learned and acted on by children in conjunction with subsequent behavioral goals eventually create the more mature responsible adult.

Adult set goals with children's input

Adults choose the goals while children are allowed to have input about them. For example, behaviors that make up the morning routine, behaviors that facilitate the transition from the classroom to the playground, behaviors involving chores, classroom routines, involving homework and so forth are goals that might be chosen by adults. It is important to choose goals that can be achieved in a concrete manner.

Concrete goals that are quantifiable

The goal of "being good" or of "being respectful," or of "not being bad" or "not disrespectful," while being worthwhile long-term goals, are NOT concrete enough. The child may be "good" or not fight for virtually the entire day but may misbehave in the last half hour before dismissal, which would disqualify him/her from achieving the goal.

Respect is hard to quantify and disrespect can be very subjective. For example, children are often told that they have had a "bad day" and if asked will report that they had been bad or disrespectful the entire day. The report makes it sound as if there was nothing at all that was positive in their behavior during the day. Had they screamed, argued, spit bit, kicked and hit from the first minute they arrived at school? There were times where the children had behaved fairly appropriately for most of the day but had lost it (especially at the end of the day when they were tired) and had acted out then. This was a "bad day." In other words, they got no credit whatsoever for the positive or benign behavior from the rest of the day. One slip up lost them any credit not only for their positive behavior but for the energy and effort to be "good." Although, respect, positive behavior, community awareness, and socially emotional maturity are the greater goals of discipline, these are too complex for a behavioral incentive plan. However, remember all these things eventually come out of a successful behavior incentive plan.

Defining and Quantifying Desirable Behaviors

Adults need to be clear about the behaviors they want from children. Avoid subjective definitions of behavior, such as the following:

"Be good-“Don't be bad""Be more helpful around the classroom or house"

Clear definitions of desirable behaviors would be,

"Do all your classwork before any free time""Put the toys and equipment back in their places"

"Be in your seat before the late bell”"Clear your desk before going to recess""Hang your coat or jacket on your hook"

Certain behaviors can be put into windows of time, such as "Be seated on the rug with your hands in your lap before the third ring of my bell," or "Have all chores done by nine o'clock," or for younger children, “Come to the circle when the big hand points to the 3 on the clock.” Quantify means yes or no, not "sort of" or "later" or "intend to." Kinda, almost, sort of do not work as quantifiable behaviors. Either a behavior is done or not done. Either a behavior is completed by a certain time or not.

Short-term, mid-term, and long-term Goals

The ADULT (through negotiation with the child) sets the short-term, mid-term, and long-term goals. If a clean desk is attractive to the teacher or parent (if not a miracle!)...if chores are...if classwork is...if lining up is... The principle is that the goals are meaningful to the teacher or parent now, and will have meaning for the child in school achievement or eventually, in life as he/she integrates them into his/her lifestyle and expectations. Short term goals may be single simple behavior changes; mid-term goals can be a set of behavior changes (all the behaviors for a good transition from one activity to another in the classroom routine); long-term goals several sets of behaviors (that promote overall positive school or household performance). The initial focus will be on the short-term goals. However, midterm and long-term goals are essential to stretch children's sense of power and control over their own lives. Even though they may be focused on short-term issues and only focus forward into a relatively short period of time, the ability to focus into the future is a major value of modern American culture. Being able to successfully anticipate to one's own benefit into the future can be one definition of wisdom. Although we do not want to cause children to lose the joy and spontaneity and existential presence of childhood, we also do not want them to suffer in the future from being oblivious in the present!

Frequency & Consistency Behavior Goals

The adult should pick minor frequency & consistency behavior goals, more substantial frequency & consistency goals, and major frequency & consistency goals. For example, the initial goal may be a successful progression through the behaviors of a clean up routine prior to going out to lunch.

The set of behaviors would be made up of putting books that in desk or shelves, returning supplies to a cabinet, putting completed or incomplete work into an appropriate titles or folders, picking up any stray paper or garbage off of the floor, and being in your seat by a certain time. Unfortunately, if the lunchtime is 12 p.m., up until 12 p.m. the books, supplies, work, garbage and seating can be delayed and argued over. Quantify these behaviors and set up reasonable expectations so that there isn't a rush in the last 5 minutes to accomplish what needs a 15 minutes for half hour to do, by setting aside deadlines for each of the behaviors.

- Specifically, the books and supplies organizing has to start by 11:45 a.m. and be done by 11:50 a.m. If it is done by 11:50 a.m., then the child is credited with achieving the goal and gains a point. If the child is not done by 11:50 a.m.... in other words, is done at 11:51 a.m.,

- then he says she has failed to achieve the goal and does not get credited a point (be merciless!). Yes or no, made it or didn't make it.

- Work placed in the appropriate place has to be finished by 11:55 a.m. Yes-no, made it or didn't make it.

- Floors clean and bottoms in seat by 12 noon. Yes or no, made it or didn't make it.

If the child achieves some of the goals, then he/she gains some of the points. If the child achieves all of the goals, then he/she gains all of the points plus a bonus (to be discussed later). If this plan motivates the child to improve the cleanup routine, he/she will also be developing habits that will benefit him/her in the long-term. Once this goal has been stable, then another goal- a more substantial goal may be set. An extension of the cleanup routine to include other school activities and chores may be an appropriate new goal. This transfers to the whole situation as well -- for example, the end of school routine. At home, getting homework done may be isolated as a goal in of itself.

Remember, No Punishments!

Punishments are not a part of this plan. Goals are behaviors that must occur frequently and consistently, that once achieved result in rewards. Never take away any earned or achieved "points." In this plan, children never lose credit for achieved goals for misbehavior. Misbehavior results in the lack of progress toward goals (and resultant rewards), but does not discredit the children's positive behavior. This avoids the focus on punishment. The negative consequence of not following through on the positive behaviors is that the goals will be achieved slowly rather than quickly and the rewards will be slow to come. The positive consequence of following through is that the goals will be achieved quickly and the rewards gained quickly... and often.

Adults Pick Goals, but the Child Picks the Rewards

Adults pick the goals because of their insight about how the classroom or household tasks or routines will benefit future life success for children. On the other hand, children are best at telling adults what motivates them now! The CHILD (through negotiation with the adult), chooses his/her own rewards. If toys are attractive to him/her...if freetime is...if privileges...if video games...if excursions... The principle is that these rewards have to be meaningful to the child- not to the adult. The child should be encouraged and led to minor, more substantial, and major rewards.

One father decided that the rewards should be books, "because books are good for him," referring to his 3 year old son. Books would have been okay as the reward if books were rewarding to his son. Unfortunately, they were not rewarding to him. He liked Pokémon cards! This plan was presented to his son by saying, "We have figured out a way for you to get on a whole bunch of Pokémon cards. Do you want to do that?" Boy, was he excited! With Pokémon cards as the award, the father found that his son was highly motivated and met the behavioral goals readily. Another way to present such a plan is to ask, "Would you be interested in a way to get a lot of the things that you want? And be in control of how fast you get them?" It may be very appropriate to coordinate rewards with the parents of certain children. A more extravagant or expensive reward can be provided by a parent versus you as a teacher may be able to afford.

Age-Appropriate and Individually Tailored Rewards

Rewards have to be age-appropriate and tailored to the individual child. Adults have to put boundaries on the rewards. They need to be reasonable and not extravagant... and also within the budget and values of the classroom or family. Another family attempted to motivate their son into bathing regularly by promising him a new videogame console if he bathed daily for a week. This was far too extravagant a reward for too simple a series of behaviors. If that was all it took to get a new videogame console, imagine the growing demands he would make for other behavior such as doing homework and getting up in the morning. What was worse, was that they gave him the videogame console after only three days. Of course, after he got the videogame console, he stopped bathing again. They sabotaged their own incentive plan.

In a classroom, teachers have to do with the reality of their curriculum and the standards and expectations of the school. A special and extravagant reward can be something that occurs very occasionally. In addition, there is added complication of developing an individual incentive plan for a child while having other children may or may not have their own incentive plans. It is also possible to develop an overall incentive plan for the entire class. However, the additional complication is whether to reward the entire class no matter how much individuals contribute, don't contribute, or actually retard the achievement of the goals. If you set up an incentive plan for the entire class, you need to accept that the contribution of individual students will differ greatly, and accept and work from the premise that the success of and rewarding of the entire class will be motivating for the individual students, including the indifferent ones.

OCCURRENCE, FREQUENCY, CONSISTENCY, AND BONUSES

More substantial and major behavioral goals should be matched up with bonus rewards- such as more money, more points to redeem, or a special excursion, privilege, or present. For example, the incentive plan can be set up so that each accomplishment- each completed behavior results in one point credited (or stars on a chart). If all of the behaviors in the set are completed, then there should be bonus points awarded. A certain number of points are gained when the set of behaviors is completed for one day. For a series of days and weeks of successful completion of behaviors, then an even greater bonus should be rewarded.

Each occurrence deserves some credit, but greater frequency deserves even greater credit, and consistency of positive behaviors deserves the highest reward. Some people feel the whole idea of rewards has being artificial and inappropriate since the real world doesn't reward you when you just do what you're supposed to do. Quite the contrary, a well-designed behavioral incentive plan does reflect the real world! For example, each time you go to work and do a good job- an occurrence, you get some pay. However, if you go to work and do a good job frequently, you will get more pay and raises in pay. On top of that, if you go to work and do a good job consistently, then you will get not only raises but promotions as well. A well-designed behavioral incentive plan becomes a model for habits and values that will promote success in the adult and vocational world.

Contracts Free Adults from Anger & Punishment

Once the adult and the child agree on the rewards and goals, then a CONTRACT can be made (writing it up and having it signed may be useful). With the contract, the adult does not need to be angry at the child or punish him/her; the adult only has to adhere to his/her part of the contract. The adult can be honestly regretful that the child has not competed his/her set of behaviors... the adult can be honestly regretful that the child will not receive the rewards that the child had selected. Often, the adult’s anger is used to punish the child. Unfortunately, anger often distracts the child from his/her responsibility in not completing the behaviors and gaining the rewards. If the child holds up his/her end, then he/she accumulates the points, achieves the goals, and gets the rewards. If he/she doesn't, then he/she doesn't! Too bad... so sad! Whether or not the child achieves the goals well or poorly, the behavioral incentive plan is reflecting how the real world works.

Don’t Expect Great Initial Results

Initial indifferent success does not mean the plan has failed. Getting angry at the failure of the child to wholeheartedly embrace the plan is counterproductive and unnecessary. Expect him/her to fail initially and save yourself the anger! Despite all the warnings, adults still get angry at children when they fail to be successful at the plan. Despite all the prior experiences with things being difficult if not impossible to accomplish with certain children, but those still expect the plan to "magically" make them change immediately. The plan will work... eventually and usually! However, did not expect these difficult children to respond exactly as you would hope. Chances are, that they will do things differently and still be difficult. And, it will still be up to you to make adaptations as needed. In other words, you the adult is still the major ingredient in this plan: your awareness, your sensitivity, your creativity, your wisdom, your flexibility... that is, you still need to be a teacher or a parent! And teach or parent! Which means observe carefully and then respond to the child's sometimes unpredictable behavior. The underlying principles of a behavioral incentive plan are still sound and appropriate. The plan will give the child the appropriate feedback depending on what he/she does. Failure to follow through will not be rewarded. Mediocre achievement will be rewarded in a mediocre manner. Exceptional compliance or achievement will be rewarded exceptionally. The adult has to do nothing, except to follow through as the contract had been established.

Don’t let yourself be manipulated! Don't lose it!

Do not save the child from (not) getting what they deserve! Another way to sabotage the contract, would (besides getting angry) be finding ways to save the child from getting the consequences of not behaving (no points, no goals, no rewards). Oppositional children can be very manipulative and tend to be experts at getting adults to change the contract to save them from the choices they have made. DON'T DO IT! If the adult "saves" the child from his/her choice, the adult effectively undermines him/herself and any possibility of the child learning a sense of responsibility. Don't give them the treat anyway... don't let them have the free time anyway... don't give them the prize anyway. Normally, this happens when the adult wants the child to do well so badly, and/or is concerned that the child will be devastated if he or she does not achieve the goal and receive the reward. Then, the adult will cave in and give the reward anyway. Sabotaging the contract would also happen if the teacher or parent invokes some violation of some new condition that has not been previously discussed, and takes away previously earned points or rewards. Don't make up new violations that had not established before hand. When you do that, it creates the effect of being arbitrary. There's nothing more frustrating to a child than to have the rules change during the process without warning. This is true for adults as well as for children.

Behavior Incentive Plans are Part of a Larger Process of Discipline

This plan can be very effective, but it depends primarily on adult following through (so don't mess up!). In addition, not all children are oppositional because of their need for power and control. Sometimes, they are oppositional because of the adult's controlling behavior. If you are a teacher and you have some intense control issues, you have made a serious career error! Trying to control a classroom of children will definitely make you crazy. Children are not supposed to be controlled and cannot be controlled. Your task is to help them develop self-control and to guide them as how to most functionally gain appropriate power and control as individuals and in communities. And, sometimes, children are oppositional because of profoundly adverse family issues. A behavioral incentive plan is part of a larger process of discipline. It normally will not work in of itself if there are other major issues. Sometimes, it is just the tool to shift the balance of negativity that has existed for years for an individual and within families. Sometimes it is part of a larger approach. If you are going to use a behavioral incentive plan, it is critical that you understand the underlying principles and use them correctly in designing it. Most behavioral incentive plans fail because people do not understand the underlying principles and subsequently, fail to design them correctly. By the way, those of you who don't or haven't used behavior incentive plans but still tend to have great relationships with children, did your informal intuitive casual behavior incentive plans or processes reflect the principles and practicalities we just discussed? I bet you got it! Way to go! Way to be!

Adaptations for Younger Children

The following includes some examples of an incentive based behavioral modification program based on points. For younger children, the plan should be made more simple (two or three levels of bonuses maximum) and have shorter time frames (a half day, one day, two or three days up to a week or two weeks only). In addition, the following example starts with a single day as the baseline. For some young children, the baseline may need to be a half day or even one period in the day and the longer goals of a month, three months, or six months inappropriate (remember NOW and NOT NOW?).

For preschoolers and for some children up through early elementary grades, the day may need to be broken up into several periods—each of the following would constitute one period: the transition from being dropped off to beginning the class, from the morning hello and activities until the first recess or break, the first recess itself, the period after the first recess, lunchtime, the period after lunch, recess, the going home transition and routine, and so forth). Then a period could be as little as an hour of positive behavior and the next level of evaluation (or set of behaviors) would be the half day or the full day. Then two or three days may be the third level and a whole week would be the fourth level. Is that too simple or easy? Well, with some of those kids, you’ll be giving yourself a reward if they have a whole solid day! If they have a great week, you have had a great week! Good luck!

INCENTIVE BASED BEHAVIORAL MODIFICATION PROGRAM FOR OPPOSITIONAL DEFIANT CHILDREN- SAMPLE PLANS

For example:

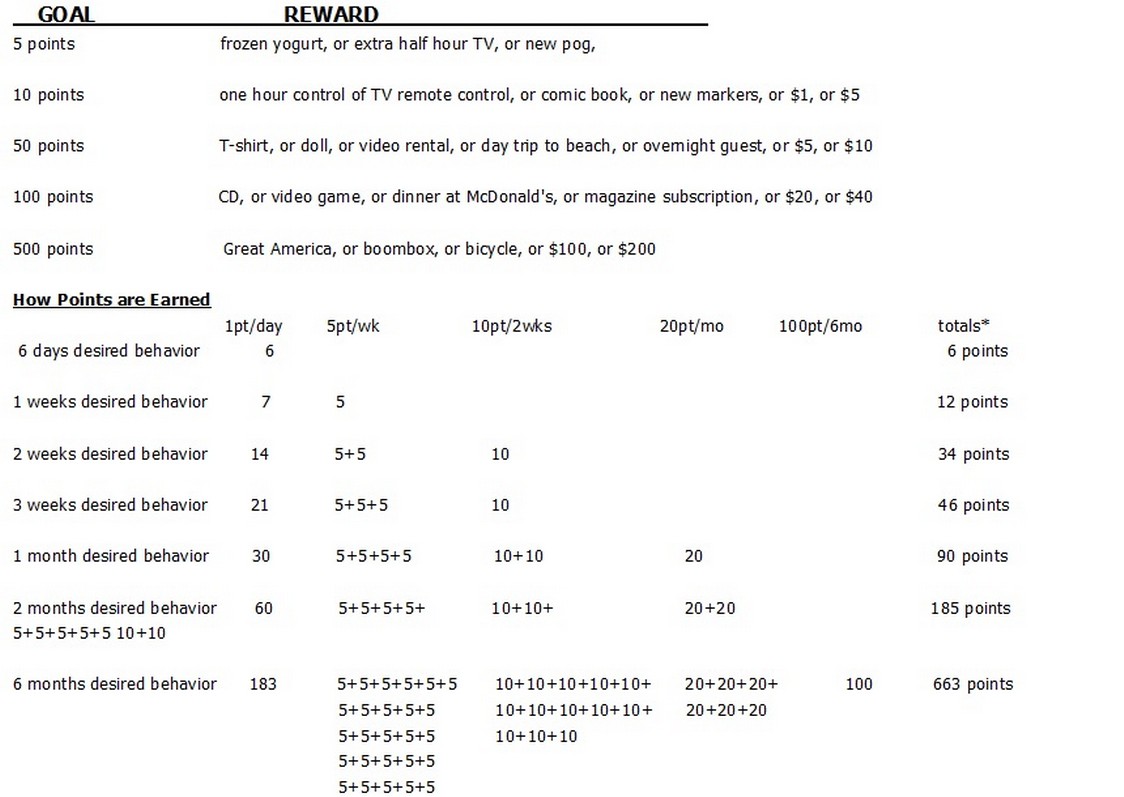

The 6 months of desired behavior earns 663 total points. The 663 points are made up of:

183 points for each of the 183 days,plus 26 five-point bonuses for each of the 26 weeks,plus 13 ten-point bonuses for each of the 13 two-week periods,plus 6 twenty-point bonuses for each of the 6 one-month periods,plus the final 100 point bonus for the six-month period.

During the same six months, someone might not have desired behavior for the entire period. Thus, they will not earn some of the bonuses and will have a lower overall point total.

*Note: Totals are accumulative. That is, the totals are for if no points are traded for rewards prior to the achievement of the goals.

- Frequency and/or consistency should be rewarded.- The greater the goal, the greater the reward. Achieving minor goals should result in minor rewards; more substantial goals have more substantial rewards; major goals have major rewards.- Children choose rewards (through negotiation with adults).- Adults choose goals (through negotiation with children).