2. Match and Change - RonaldMah

Ronald Mah, M.A., Ph.D.

Licensed Marriage & Family Therapist,

Consultant/Trainer/Author

Main menu:

2. Match and Change

Therapist Resources > Therapy Books > Roles Rigidity Repair in Relationships

Roles, Rigidity, Repair, and Renovation in Relationships and Therapy

Chapter 2: MATCH AND CHANGE

by Ronald Mah

Structural therapy as is the case with other theories/therapies tends to match well with certain client presentations. Cognitively oriented therapies tend to work well with clients who are able to rationally examine and process thoughts and how they translate into behavior. Clients who have difficulty processing their emotional energy often benefit from emotionally cathartic therapies. Various other theories and therapies may match up with different client presentations, including some specific cultures. "Structural family therapy focuses on family hierarchy and holds that parents should be in charge of their children (Minuchin, 1974). This principle seems to fit well with Thai culture in which hierarchy in relationships, both inside and outside of families, is emphasized. Thai culture holds that problems take place when the executive power in the family is not in the appropriate order. Structural therapists also look for clarity and flexibility of boundaries; among parent, sibling, and couple subsystems. They believe that dysfunction occurs when differentiation between subsystems is not clear (Minuchin, 1974)" (Pinyuchon and Gray, 1997, 223). The therapist should consider if the client he or she is working with has similar systemic issues, as well as if cultural or family-of-origin expectations may be similar

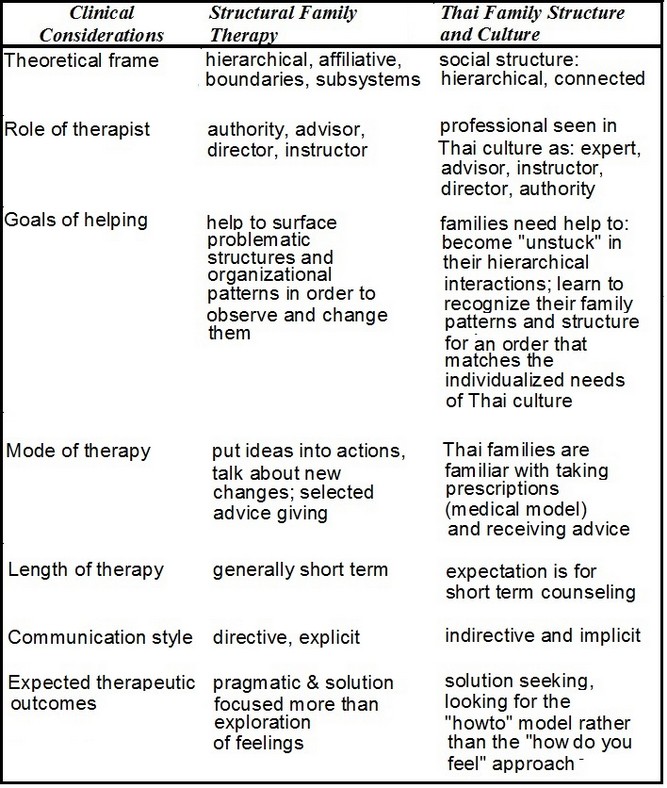

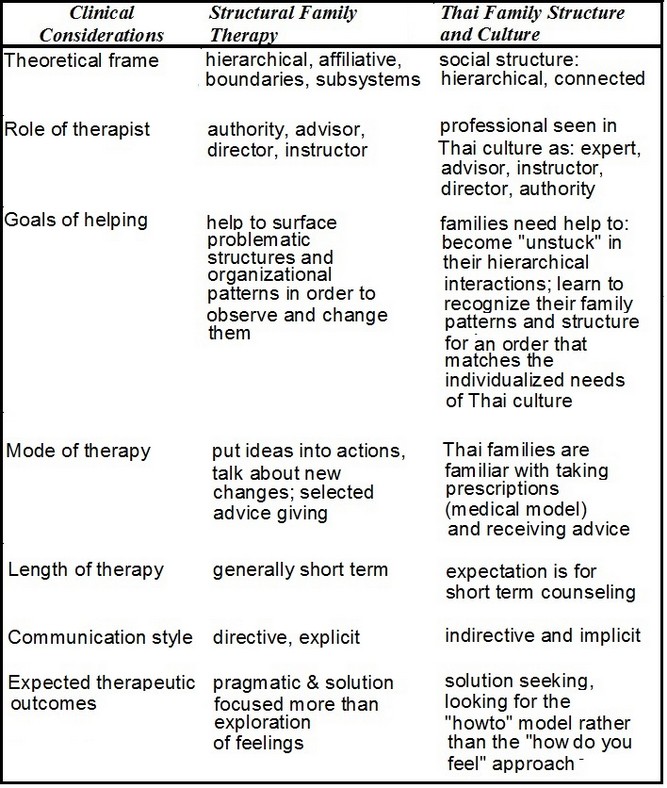

The following is a chart that summarizes several clinical considerations of structural family therapy in comparison to Thai family structure and culture. Aside from communication style, there is marked match between the two.

Illustration of Similarities and Differences Between

Structural Family Therapy and Thai Family Structure and Culture

The apparent difference between the directive communication style of the therapist and the more indirect and implicit communication style of Thai culture is not a mismatch per se. Indirect and implicit communication may the norm in Thai culture, but the more important clinical consideration is that of the role of the therapist to be an authority, advisor, director, or instructor. The structurally oriented therapist matches well with the Thai expectation for a professional to be an expert, advisor, instructor, director, and authority. The therapist may find it beneficial to assess the style and expectations of the client relative to:

Theoretical frameRole of therapistGoals of helpingMode of therapyLength of therapyCommunication styleExpected therapeutic outcomes

Clients from similar ethic communities (such as other Asian, people of color, or traditional non-Western, under developed societies) or in a current relationship, couple, or family that or whose family-of-origin displays similar attitudes, values, beliefs, and behaviors may find structural approaches in sync with their style and expectations. The therapist can benefit from using Pinyuchon and Gray's chart not merely in a potentially isolated or rare situation in the United States working with Thai or Thai-American clients, but for examining any relationship, couple, or family for his or her clinical use of structural therapy assessment, interventions, and strategies.

Couples in the American mainstream culture are ostensibly equal partners in the relationship. In many other cultures, there is no assertion or illusion of equality between the couple. Often, a culture may place the father clearly the head of the household. However, there may also be qualifications to this in a multi-generational extended family system. The grandfather, great-grandfather, or eldest male would be the leader of the family. In functional but unequal systems, a lower hierarchy position still may allow for relative respect and power and control. The lesser role in decision-making may still allow for significant influence within the family, and still be very critical for the overall well-being of the family. It remains important for the therapist to examine the systems or structures both within and around the couple. "Couples seeking marital therapy can benefit from therapeutic approaches that directly confront the larger context of negative societal assumptions about how parents are supposed to handle the challenges of balancing family life with career. When couples describe their feelings of stress, inadequacy, and exhaustion from trying to fulfill endless expectations, therapists can make overt the cultural framework that has contributed to those pressures and expectations" (Zimmerman, 2000, page 349). The couple and the couple as a family needs to be examined as "a psychosocial system, embedded within wider social systems, which functions through transactional pattern; these transactions establish patterns of how, when and to whom to relate, and they underpin the system" (Vetere, 2001, page 134).

Ted and Jann when presenting for therapy come with problems in their relationship and dynamics. Whether they are conscious of it or not, they also bring deeper and wider interactional patterns and expectations into the relationship that may have significant influence on their functioning. Ted was born in Hong Kong and immigrated to the United States as a seventeen year old teen. Jann was born in Japan and immigrated to the United States when she was five years old. Although they are both Asian, Ted's Hong Kong Chinese gang-involved street background was very different from Jann's family experience as Japanese business entrepreneurs. They shared the experience of immigration, but from significantly different developmental stages. Jann came as a young child who learned English and was largely Americanized when they met as young adults. On the other hand, Ted who had a significant Chinese accent speaking English and was clearly more Hong Kong Chinese culturally than American culturally. These are just a couple of potentially relevant systemic or cultural influences for the therapist to consider in therapy. In a couple's presentation for example, where the family structure revolves around challenges of one parent working outside of the home while the other parent is the primary household and child caregiver, there may be underlying cultural and historical assumptions that bear examination. In many lower to middle income families, families of color, and single-parent families, taking one parent out of the economic picture is not and has not been a viable option. Such families may have difficulty surviving financially with two incomes. With single-parent families, there is not a second income option or the option of a non-existent partner staying at home. Social, religious, professional, and moral commentary may judge such parents or families as choosing against the best interests of their children, when in fact there is no choice.

An individual alone or as a couple may arrive in therapy due in part to guilt that their work situations imply that they care less about their children, are less involved, and just are not good parents. "These assumptions are particularly damaging when they are religion-based. When society gives a message that the more spiritual path is a stay-at-home mother arrangement, this discounts the spiritual commitment of poor families and families making other choices" (Zimmerman, 2000, page 351). The therapist may find that one or both partners in the couple hold significant shame and subsequently also hold significant unexpressed anger at oneself or the partner for not economically enabling one parent to stay at home as a caregiver. Jann's Japanese family background coupled with support from traditional American values caused her to resent her need to work to make ends meet for the family. Ted's working class Chinese cultural family values largely coincided with both Jann's and traditional American values, although his own family experience was of both his parents working throughout his childhood. His father and mother silently accepted the necessity of both of them working, and he expected that he and Jann would also silently accept the family requirements.

When considering structural models for the relationship, couple, or family, the therapist should also be aware that societal or cultural models are often in flux. As such, traditional models of couples or family relationships may be more or less relevant. Similarly, current models may also be more or less relevant. When Ted immigrated from Hong Kong in the early 1970s, Hong Kong was still under British control and had a unique blend of Chinese and British social dynamics. Since his personal existence in Hong Kong ended when he was seventeen in the early 1970s, he had no experience of the major and tumultuous changes that occurred when Hong Kong was returned to China, which was now part of a communist country instead of an imperial territory. As a result, the therapist could be misled to think that Ted's cultural orientation would be comparable to current Hong Kong social standards. His adolescent absorption of attitudes, values, beliefs, and behaviors essentially froze in time upon leaving Hong Kong. Yet at the same time, it may be inaccurate to assume that his cultural mindset could be considered that of 1970s Hong Kong. His eventual reconciliation of what and how to be a husband, a father, and a man in an indigenous Hong Kong context would have been different than it became in the initially unfamiliar and alien United States. It may have been reasonable at one time to assume that individuals separated by decades and even centuries from in an essentially unchanged society would have fairly identical cultural beliefs and behaviors. However, the therapist needs to consider whether the rapid transformation of societies in the modern technologically advanced and influenced era challenges his or her assumptions of the cultural standards of his or her clients. This occurs both within the United States and in other countries. For example, consider the relevance of the following commentary to changes in the United States, especially in the last several decades or century.

"Both urban and rural Thai communities are in transition today. In the country people live in agricultural villages. Historically, farming villages required the labor of family members, relatives, and neighbors, resulting in a high degree of integration among those composing a communal work group (Soonthornpasuch, 1963). This does not hold true in the 1990s. Communal farming is now rarely practiced. Rapid socioeconomic development in the past decade has had a great impact on the function and structure of Thai families. Wongsith (1994) noted that as Thai society gradually becomes less agricultural and more industrialized and urbanized, the family is being transformed from an extended to a nuclear structure. This trend applies to both rural and urban families. Urban society differs considerably from rural life and is relatively more westernized. Urban Thailand has a wider variety of occupations and greater numbers of ethnic groups. Family members in urban families do not usually work at the same occupations. The relationship between family, relatives and neighbors is less closely knit than in rural communities. In urban areas in Thailand, traffic congestion is an obstacle for family members who work away from their homes. Public transportation in Thailand does not effectively reduce traffic and traveling problems. People who are forced to work miles away from home due to economic pressures have difficulty finding time for their children, siblings, relatives, and spouses. The need to be close, cared for, to spend time with family, and to have personal time has become a major psychological concern for families" (Pinyuchon and Gray, 1997, page 210-11).

Pinyuchon and Gray's commentary on Thai society are highly comparable to changes in the United States over the past several generations. They note that family size in Thailand has decreased in the last decade with accompanying changes in family types and living arrangements. "Almost 20 years ago, 50 to 60 percent of all Thai family households were nuclear families (Smith, 1979). Nuclear family households in both rural and urban areas have increased since that time (Muscat, 1994)" (page 211). The extended family structure that was common in Thailand with parents along with married children and his or her spouse and children has become a temporary situation. As the adult children become more financial independent, they move out to establish their own household. This is similar to older American models of extended families, and recently appears to be returning as a more common model as well because of ongoing economic constraints. In Thailand "Situations where three generations live together as an extended family are gradually decreasing" (Muscat, 1994) (page 211), whereas in the United States they may be gradually increasing. The therapist should consider not only what each partner holds as the standards and expectations of the relationship, couple, or family, but if there has been changes in the functional model. Of relevance also would be whether changes are in the current or had occurred in a prior generation, and how the changes were perceived: positively or negatively, as inevitable or by choice. If changes are considered negative- sometimes, considered negative simply because they differ from traditional expectations, clients would ask the therapist to repair or restore the prior model. Key would be if older (or newer) models match up with the demands the individual, couple, or family faces. However, if the old models prove ineffective in a new context, then repair or restoration would not be beneficial. On the other hand, if changes are considered positive, then the renovation of relationship models and functioning can be guided by the therapist. In any case, the therapist needs to assess the potential cross-cultural conflicts and assess without bias for functionality in the relevant circumstances, before venturing repair or restoration versus renovation or remodeling